Agricultural Development in Western Central Asia in the Chalcolithic and Bronze Ages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Emerging Picture of the Neolithic of Northeast Iran

IranicaAntiqua, vol. LI, 2016 doi: 10.2143/IA.51.0.3117827 AN EMERGING PICTURE OF THE NEOLITHIC OF NORTHEAST IRAN BY Kourosh ROUSTAEI (Iranian Center for Archaeological Research) Abstract: For many years the Neolithic of the northeastern Iranian Plateau was acknowledged by materials and data recovered from the three sites of Yarim Tappeh, Turang Tappeh and Sang-e Chakhmaq, all excavated in the 1960-1970s. In the last two decades an increasing mass of information based on archaeologi- cal fieldworks and reappraisal of archival materials have been built up that is going to significantly enhance our understanding on the Neolithic period of the region. The overwhelming majority of the information is obtained from the Shahroud area and the Gorgan plain, on the south and north of the Eastern Alborz Mountains respectively. So far, sixty two Neolithic sites have been identified in the region. This paper briefly reviews the known Neolithic sites and outlines the various implications of the newly emerging picture of the period for the northeast region of Iran. Keywords: Neolithic, northeast region, Sang-e Chakhmaq, Shahroud, Gorgan plain, Jeitun Culture Introduction Since Robert Braidwood’s pioneering investigations in the Zagros Mountains in 1960s (1961), western Iran has been the interest area for scholars who searching the early evidence of domestications. The follow- ing decades witnessed a series of well-planned works (e.g. Hole et al. 1969) in the region that considerably contributed to our understanding on early stages of the village life. Renewal of the relevant investigations in the Zagros region in recent years points the significance of the region on the incipient agriculture in the Near East (e.g. -

Revisiting the Geo-Political Thinking of Sir Halford John Mackinder: United States—Uzbekistan Relations 1991—2005

Revisiting the Geo-Political Thinking Of Sir Halford John Mackinder: United States—Uzbekistan Relations 1991—2005 A thesis Presented to the Faculty of The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy by Chris Seiple In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 27 November 2006 Dissertation Committee Andrew C. Hess, Chair William Martel Sung-Yoon Lee Chris Seiple—Curriculum Vitae Education 1999 to Present: The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University: PhD Candidate 1994 to 1995: Naval Postgraduate School: M.A. in National Security Affairs 1986 to 1990: Stanford University: B.A. in International Relations Professional Experience 2003 to Present President, the Institute for Global Engagement (IGE) 2001 to 2003 Executive Vice President, IGE 1996 to 1999 National Security Analyst, Strategic Initiatives Group, Headquarters, United States Marine Corps 1997 National Security Affairs Specialist, National Defense Panel 1996 Liaison Officer, Chemical-Biological Incidence Response Force 1990 to 1994 Infantry Officer, United States Marine Corps Publications • Numerous website articles on Christian living, religious freedom, religion & security, engaging Islam, just war, and Uzbekistan (please see the website: www.globalengagement.org) • “America’s Greatest Story.” The Review of Faith & International Affairs. 4, no. 2 (Fall 2006): 53-56. • “Uzbekistan and the Bush Doctrine.” The Review of Faith & International Affairs. 3, no. 2 (Fall 2005): 19-24. • “Realist Religious Freedom: An Uzbek Perspective.” Fides et Libertas (Fall 2005). • “Understanding Uzbekistan,” an Enote publication distributed by the Foreign Policy Research Institute (1 June 2005). • “Uzbekistan: Civil Society in the Heartland.” Orbis (Spring, 2005): 245-259. • “Religion & Realpolitik,” St. Paul Pioneer Press, 12 November 2004. -

Kolb on Christian, 'History of Russia, Central Asia and Mongolia, Volume I: Inner Eurasia from Prehistory to the Mongol Empire'

H-Asia Kolb on Christian, 'History of Russia, Central Asia and Mongolia, Volume I: Inner Eurasia from Prehistory to the Mongol Empire' Review published on Friday, October 1, 1999 David Christian. History of Russia, Central Asia and Mongolia, Volume I: Inner Eurasia from Prehistory to the Mongol Empire. Oxford and Malden, Mass.: Blackwell Publishers, 1998. 464 pp. $62.95 (cloth), ISBN 0-631-183213; $27.95 (paper), ISBN 978-0-631-20814-3. Reviewed by Charles C. Kolb (National Endowment for the Humanities.)Published on H-Asia (October, 1999) A History of Russia, Central Asia, and Mongolia (Volume I) [Disclaimer: The opinions expressed herein are those of the reviewer and not of his employer or any other federal agency.] This review is divided into three sections: 1) Background and General Assessment, 2) Summary of Contents, and 3) Final Assessment, including a comparison with other English language works. Background and General Assessment "The Blackwell History of the World" Series (HOTW), Robert I. Moore, General Editor, is designed to provide an overview of the history of various geophysical regions of the globe. The HOTW contributions are each prepared by a single authority in the field, rather than as multi-authored, edited works. These syntheses are published in both paperback and cloth, making them appealing for pedagogy and students' budgets, and as a durable edition for libraries. The current volume, third in a projected series of sixteen works, follows the publication of A History of Middle and South America by Peter Bakewell (August 1997) and A History of India by Burton Stein (May 1998). -

A Brief Discussion on Archaeological Sites and Main Discoveries in Archaeobotany in Central Asia

17 Malaysian Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities (MJSSH), Volume 3, Issue 5, (page 17 - 29), 2018 Malaysian Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities (MJSSH) Volume 3, Issue 5, November 2018 e-ISSN : 2504-8562 Journal home page: www.msocialsciences.com Agropastoralism and Crops Dispersion: A Brief Discussion on Archaeological Sites and Main Discoveries in Archaeobotany in Central Asia Muhammad Azam Sameer1, Yuzhang Yang1, Juzhong Zhang1, Wuhong Luo1 1Department of History of Science and Scientific Archaeology, School of Humanities and Social Science, University of Science and Technology of China Correspondence: Muhammad Azam Sameer ([email protected]) Abstract ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ The sub-branch of archaeology, called archaeobotany connects present-day man with ancient plants. The ancient plant remains to give the picture of agro-pastoralists activities in Central Asia. Through the plant remains, the way of living, food habits, vegetation, economy and agricultural developments of Central Asia have been traced out. Archaeological sites give new insights of the agricultural denomination in the region, which revealed marked differences. Through archaeobotanical investigation of the plant remains like bread wheat (Triticum aestivum), rice (Oryza sativa), foxtail millet (Setaria italica), broomcorn millet (Panicum miliaceum), six-row barley (Hordeum vulgare), and other plant fossils provide new prospects about ancient food production in the expanse of Central Asia. A brief discussion on Central Asian archaeological sites and recovered plant remains as well as the agricultural exchange of Central Asia with the neighboring regions are the worthy discussion and essence of this paper. Keywords: archaeobotany, archaeological sites, plant fossils, agropastoralism ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ Introduction Archaeobotany furnishes the connection of ancient plants with the ancient people (Miller, 2013). -

Chakhmaq Abstract.Pdf

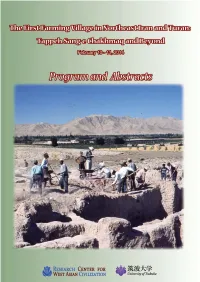

The First Farming Village in Northeast Iran and Turan: Tappeh Sang-e Chakhmaq and Beyond February 10 - 11, 2014 Program and Abstracts February 10th (Monday):(Advanced Research Building A, 107) 13:00-13:10 Opening address Akira Tsuneki (University of Tsukuba) 13:10-13:30 Geologic setting of Tappeh Sang-e Chakhmaq Ken-ichiro Hisada (University of Tsukuba) 13:30-13:50 The site of Tappeh Sang-e Chakhmaq Akira Tsuneki (University of Tsukuba) 13:50-14:10 Radiocarbon dating of charcoal remains excavated from Tappeh Sang-e Chakhmaq Toshio Nakamura (Nagoya University) 14:10-14:40 Coffee break 14:40-15:00 Pottery and other objects from Tappeh Sang-e Chakhmaq Akira Tsuneki (University of Tsukuba) 15:00-15:20 Mineralogical study of pottery from Tappeh Sang-e Chakhmaq Masanori Kurosawa (University of Tsukuba) 15:20-15:40 Figurines of Tappeh Sang-e Chakhmaq Setsuo Furusato (Matsudo City Board) 15:40-16:10 Coffee break 16:10-16:30 Neolithisation of Eastern Iran : New insights through the study of the faunal remains of Tappeh Sang-e Chakhmaq Marjan Mashkour (Central National de la Recherche Scientifique) 16:30-16:50 Charred remains from Tappeh Sang-e Chakhmaq, and a consideration of early wheat diversity on the eastern margins of the Fertile Crescent Dorian Fuller (University College London) 18:00-20:00 Welcome party II February 11th (Tuesday): (Advanced Research Building B, 108) 10:00-10:20 Vegetation of the Chakhmaq site based on charcoal identification Ken-ichi Tanno (Yamaguchi University) 10:20-10:40 Human remains from Tappeh Sang-e Chakhmaq Akira -

Oil and Gas Industry of Turkmenistan

Oil and Gas Industry of Turkmenistan March 2009 Oil and Gas Industry of Turkmenistan AUTHOR RPI is acknowledged as a leading research consulting firm specializing in the energy industry of Russia, the Caspian region, Eastern and Central Europe. Formed in 1992, RPI provides an integrated set of services, ranging from strategic planning to corporate intelligence and M&A support. RPI’s clients include investors, contractors and financial institutions involved in oil, gas and power projects in Eurasia and globally. RPI’s expertise extends to all major sectors and aspects of the oil, gas and power business, including, but not limited to E&P, transportation and exports, refining and petrochemicals, infrastructure, equipment and services, as well as economic and financial issues. Since 1992 RPI has produced over 50 research studies and reports, the catalogue of which is available upon request. PUBLISHER’S NOTE Information herein, and any opinions expressed herein, has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable. The authors have verified it to the best of their ability. Nonetheless, RPI does not make claims as to its accuracy or completeness, and it should not be relied upon as such. Part of the maps contained in the report were designed based on maps from the Petroleum Economist World Energy Atlas 2007. To get additional information on RPI’s reports and studies, please contact Vsevolod Prosvirnin by phone at: +7(495) 778 4597 / 778 9332 or by email: [email protected] RPI Moscow Krasnopresnenskaya nab., 12, Suite 1101, World Trade Center, Moscow 123610 Russia Author copyrights are protected by applicable laws and regulations. -

About RECENT Excavations at a Bronze AGE SITE in MARGIANA (TURKMENISTAN) Sandro Salvatori

2007] FARFALLE NELL’EGEO 11 ABOUT RECENT EXcavations at A BRONZE AGE SITE IN MARGIANA (Turkmenistan) Sandro Salvatori Abstract A recently published book on the Adji Kui 9 Bronze Age site excavation (Murghab Delta, Turkmenistan), deserves close inspection in the context of the 3rd millennium BC history and archaeology. Introduction Central Asia republics, of western archaeologists 5 and the beginning of joint archaeological projects A full-scale overview of Central Asian archaeo- with local institutions and researchers. It soon be- logy, from the beginning of the research to the ear- came clear that different, irreconcilable, excavation ly 1980s, was published in 1984 by Ph. L. Kohl. A methods and theoretical approaches were being few years later, an appreciable synthesis was pub- used by the two schools. lished by H.-P. Francfort 1 on the Shortughai ex- As for excavation methods, two main opposing cavations in north-eastern Afghanistan. The most and antagonistic approaches were and still are at interesting book on Turkmenistan is by Fred Hie- work: Approach 1 is an uncontrolled approach to bert 2 and provides a good updated survey of the excavation of architectural complexes without con- archaeological research in Margiana up to the early sidering stratigraphic procedures and recording. 1990s. Approach 2 points to understanding and recording Since that date, fieldwork has been carried out cultural variability using archaeological stratigra- at a number of new and old sites, both along the phic methods as dictated by the evolution of the Turkmenistan piedmont and in Margiana 3. In ad- discipline all over the world. dition, an international project aimed at providing A third, apparently harmonising behaviour (Ap- an updated Archaeological Map of the Murghab proach 3), pays some attention to record stratigra- delta 4 has been ongoing since 1990. -

The Foreign Service Journal, April 2003.Pdf

Earn more than 30,000 Bonus Points, 7,500 Bonus Miles, or whatever rotates your tires. Announcing the Just register now and pick the rewards track you want to earn on—points, miles, or racing rewards. Then stay between April 1 and June 15, 2003, at any of the 2,300 U.S. hotels in the Priority Club ® Rewards family of brands, and use your Visa ® card to book and pay. Starting with your second qualifying stay, you’re on your way to earning your choice of great rewards! Choose Your Rewards Track STAYS STAYS STAYS STAYS Points or Miles 1,500 Points or 3,000 Points or 6,000 Points or 20,000 Points or Track 350 Miles 750 Miles 1,500 Miles 5,000 Miles Coca-Cola® Racing Coca-Cola Racing Coca-Cola Racing Family Real Stock-Car Racing Racing Family Driver Family Bobbing Head Miniature Replica Hood or at the Rewards Track Car Flag or Figure or Watch One-Year Subscription to Dale Jarrett Collectible Pin Set Track PassTM Racing Adventure Register today at priorityclub.com/racetrack or call 1-800-315-3464. Be sure to have your Priority Club Rewards member number handy. Not a member yet? Enroll for free online or by phone. © 2003 Six Continents Hotels, Inc. All rights reserved. Most hotels are independently owned and/or operated. Stays must be booked and paid for using a Visa card to be eligi- ble. Offer valid in U.S. hotels only. For full details, terms, and conditions of this promotion, visit priorityclub.com/racetrack or call 1-800-315-3464. -

Proto-Indo-Europeans: the Prologue

Proto-Indo-Europeans: The Prologue Alexander Kozintsev Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography, Saint-Petersburg and Saint-Petersburg State University, Russia This study collates linguistic, genetic, and archaeological data relevant to the problem of the IE homeland and proto-IE (PIE) migrations. The idea of a proto-Anatolian (PA) migration from the steppe to Anatolia via the Balkans is refuted by linguistic, archaeological, and genetic facts, whereas the alternative scenario, postulating the Indo-Uralic homeland in the area east of the Caspian Sea, is the most plausible. The divergence between proto-Uralians and PIEs is mirrored by the cultural dichotomy between Kelteminar and the early farming societies in southern Turkmenia and northern Iran. From their first homeland the early PIEs moved to their second homeland in the Near East, where early PIE split into PA and late PIE. Three migration routes from the Near East to the steppe across the Caucasus can be tentatively reconstructed — two early (Khvalynsk and Darkveti-Meshoko), and one later (Maykop). The early eastern route (Khvalynsk), supported mostly by genetic data, may have been taken by Indo-Hittites. The western and the central routes (Darkveti-Meshoko and Maykop), while agreeing with archaeological and linguistic evidence, suggest that late PIE could have been adopted by the steppe people without biological admixture. After that, the steppe became the third and last PIE homeland, from whence all filial IE dialects except Anatolian spread in various directions, one of them being to the Balkans and eventually to Anatolia and the southern Caucasus, thus closing the circle of counterclockwise IE migrations around the Black Sea. -

Southern Turkmenistan in the Neolithic Period: a Short Historiographical Review

Herausgeber*innenkollektiv, eds. 2021. Pearls, Politics and Pistachios. Essays in Anthropology and Memories on the Occasion of Susan Pollock’s 65th Birthday: 505–18. DOI: 10.11588/propylaeum.837.c10763. Southern Turkmenistan in the Neolithic Period: A Short Historiographical Review AYDOGDY KURBANOV* Introduction north of Chopan), Pessejik Depe (1.5 km to the north-west of Togolok), Jeitun (20 km to A large number of settlements attributed to the north-west of Ashgabat), New Nisa - Taze the early Jeitun village communities of the Nusay in Turkmen (within the city limits of Neolithic period (7th–5th millennia BCE) are Ashgabat, near the village of Bagir), Kepele located in southern Turkmenistan, on the (25 km to the north of Ashgabat), Kelata, northern piedmont plain of the Kopet Dag, Yarty Gumbez, and Kantar. from the modern town of Serdar (former Gyzylarbat) to the village of Chache ( Harris 3) The eastern group, “Atek” (between the et al. 1996, 424, Fig. 1). Here, in ancient times, villages of Ak Bugday and Chache). The lands suitable for agriculture were limited eastern group includes Chagylly Depe, by the hills of Kopet Dag on one side and by Monjukli Depe, Chakmakly Depe, and the sand ridges of the Karakum desert on the Gadymy Depe. All of them are situated other. During investigations of the Soviet era, around the modern villages of Mane and 18 sites of the Neolithic Jeitun period were Chache in the Kaka district of Ahal province discovered. O. Berdyev (1969, 55–60) divided of Turkmenistan (Masson 1971, 44; Sarianidi the sites, by their geographic location, into 1992, 116; Korobkova 1996, 37). -

Agro-Pastoral Strategies and Food Production on The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kosmopolis University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology Papers and Anthropology 2015 Agro-Pastoral Strategies and Food Production on the Achaemenid Frontier in Central Asia: A Case Study of Kyzyltepa in Southern Uzbekistan Xin Wu University of Pennsylvania Naomi F. Miller University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Pam Crabtree Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.upenn.edu/penn_museum_papers Part of the Agricultural and Resource Economics Commons, Agricultural Economics Commons, Agronomy and Crop Sciences Commons, Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Asian History Commons, Botany Commons, Economic History Commons, and the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons Recommended Citation Wu, X., Miller, N. F., & Crabtree, P. (2015). Agro-Pastoral Strategies and Food Production on the Achaemenid Frontier in Central Asia: A Case Study of Kyzyltepa in Southern Uzbekistan. Iran, LIII 93-117. Retrieved from http://repository.upenn.edu/ penn_museum_papers/1 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. http://repository.upenn.edu/penn_museum_papers/1 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Agro-Pastoral Strategies and Food Production on the Achaemenid Frontier in Central Asia: A Case Study of Kyzyltepa in Southern Uzbekistan Abstract This article discusses aspects of the agro-pastoral economy of Kyzyltepa, a late Iron Age or Achaemenid period (sixth–fourth century BC) site in the Surkhandarya region of southern Uzbekistan. The na alysis integrates archaeobotanical and zooarchaeological analyses with textual references to food production and provisioning in order to examine local agro-pastoral strategies. -

Wikivoyage Turkmenistan March 2016 Contents

WikiVoyage Turkmenistan March 2016 Contents 1 Turkmenistan 1 1.1 Regions ................................................ 1 1.2 Cities ................................................. 1 1.3 Other destinations ........................................... 2 1.3.1 Archaeological sites ...................................... 2 1.3.2 Medieval monuments ..................................... 2 1.3.3 Nature reserves ........................................ 3 1.3.4 Pilgrims’ shrines ........................................ 4 1.4 Understand .............................................. 5 1.4.1 People ............................................. 6 1.4.2 Terrain ............................................ 6 1.4.3 Holidays ............................................ 6 1.4.4 Climate ............................................ 7 1.4.5 Read ............................................. 7 1.5 Get in ................................................. 7 1.5.1 Vaccinations .......................................... 7 1.5.2 Visa .............................................. 7 1.5.3 Registration .......................................... 7 1.5.4 Travel permits ......................................... 8 1.5.5 By plane ............................................ 8 1.5.6 By train ............................................ 8 1.5.7 By car ............................................. 8 1.5.8 By bus ............................................. 8 1.5.9 By boat ............................................ 9 1.6 Get around ..............................................