A Conversation Between Landscape Architecture and Public Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arts & Culture

An Invitation to All Bowen Islanders Advancing ARTS & CULTURE on Bowen Island 2017 - 2027 Cultural Master Plan TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ................................................. 3 A. Introduction ......................................................... 13 B. Our Guiding Principles ....................................... 20 C. What is Bowen’s Culture? .................................. 21 D. Goals, Strategies and Actions............................ 27 E. Plan Evaluation & Review ................................... 58 F. BOWEN 2025: A Thriving Arts-and-Culture Driven Community ..................... 59 Appendix I Status Of 2004 Cultural Plan Recommendations Appendix II Successes And New Challenges Identified Appendix III BIAC Core Programs/Budget Appendix IV Arts & Cultural Survey Highlights Appendix V Groups Consulted in Developing This Plan Appendix VI Interview Questions Appendix VII 78 Communications & Publicity Appendix VIII List of Research Documents DRAFTAppendix IX List of Abbreviations Appendix X Links to 2004 Cultural Plan, Terms of Reference and Other Documents Appendix XI Master Plan Budget Page 2 Bowen Island Cultural Plan “Bowen is a place where people can become who they want to be.” – Andrea Verwey EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Introduction Why does Bowen Island need a Cultural “Master” Plan? Culture and art happen, planned or not. The motivation for developing a vision and goals along with a strategy to achieve those goals flows from the growing recognition and acknowledgment that arts are integral to our human existence. Culture engages minds, enriches the education of children, and supports lifelong learning. Culture helps define the character or identity of a community in which people feel a sense of belonging. It engages citizens in activities that help build a sense of community, resilience, and civic engagement. Finally, as the community grows, culture celebrates diversity and helps newcomers feel welcome. -

Saccharomyces Cerevisiae

Novel strategies for engineering redox metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae Víctor Gabriel Guadalupe Medina 2013 Novel strategies for engineering redox metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Technische Universiteit Delft, op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof. ir. K.Ch.A.M. Luyben, voorzitter van het College voor Promoties, in het openbaar te verdedigen op maandag 14 oktober 2013 om 15:00 uur door Víctor Gabriel GUADALUPE MEDINA Magíster en Ciencias de la Ingeniería, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, geboren te Rancagua, Chili. Dit proefschrift is goedgekeurd door de promotor: Prof. dr. J.T. Pronk Copromotor: Dr. ir. A.J.A. van Maris Samenstelling promotiecommissie: Rector Magnificus, voorzitter Prof. dr. J.T. Pronk, Technische Universiteit Delft, promotor Dr. ir. A.J.A. van Maris, Technische Universiteit Delft, copromotor Prof. dr. J.G. Kuenen, Technische Universiteit Delft Prof. dr. R.A.L. Bovenberg, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen / DSM Prof. dr. B.M. Bakker, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen Prof. dr. J. Förster, Technical University of Denmark / Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Biosustainability Dr. R.A. Weusthuis, Wageningen University Prof. dr. M.C.M. van Loosdrecht, Technische Universiteit Delft, reservelid The studies presented in this thesis were performed at the Industrial Microbiology section, Department of Biotechnology, Delft University of Technology, The Netherlands and part of Program 1 ‘Yeast for chemicals, fuels and chemicals’ of the Kluyver Centre for Genomics of Industrial Fermentation, which is supported by the Netherlands Genomics Initiative. The cover of this thesis was designed by Manuel Toledo Otaegui (www.toledotaegui.com). The photograph was kindly provided by Michael Grab, rock balancing artist (www.gravityglue.com). -

Just Above Midtown, Where David Hammons, Fred Wilson, and Others Exhibited, Received Slightly More Press Than Kenkeleba

The Black and White Show LORRAINE O’GRADY OUTSIDE, EAST SECOND STREET between Avenues B and C only by telegram. Give that boy another chance! But after in 1983 was Manhattan’s biggest open-air drug supermarket. promising two new canvases for the show, Basquiat pulled It was always deathly quiet except for the continual cries of out. Obligations to Bruno Bischofberger came fi rst. Walking vendors hawking competing brands of heroin: “3-5-7, 3-5-7” down East Second Street was like passing stacks of dreams in and “Toilet, Toilet.” From the steps of Kenkeleba, looking mounds. I asked muralist John Fekner to connect the inside across at the shooting galleries, you saw unrefl ecting win- with the outside. Downtown had a multitude of talents and dows and bricked-up facades, like doorless entrances to trends, some being bypassed by the stampede to cash in. The Hades. How did the junkies get inside? There was almost no show ended with twenty-eight artists, many still worried that traffi c. Behind the two columns fl anking Kenkeleba’s door- cadmium red cost thirty-two dollars a quart wholesale. Each way unexpectedly was a former Polish wedding palace in ele- day as I approached the block, I wondered, “Where is my gant decay owned by a black bohemian couple, Corrine mural?” On the day before the opening, it was there. John Jennings and Joe Overstreet. had done it at 4 am, when even junkies sleep. The gallery, invisible from the street, had fi ve rooms— Inside the gallery, it pleased me that, even across so many one, a cavern—plus a corridor, and dared you to use the styles, the images gave off language. -

Vol. 24, No. 3 March 2020 You Can’T Buy It

ABSOLUTELY FREE Vol. 24, No. 3 March 2020 You Can’t Buy It The NC Museum of Art in Raleigh, NC, will present Front Burner: Highlights in Contemporary North Carolina Painting, curated by Ashlynn Browning, on view in the Museum’s East Building, Level B, Joyce W. Pope Gallery, from March 7 through July 26, 2020. Work shown by Lien Truong © 2017 is I, “Buffalo”, and is acrylic, silk, fabric paint, antique gold-leaf obi thread, black salt and smoke on linen, 96 x 72 inches. I “Buffalo” was purchased by the North Carolina Museum of Art with funds from the William R. Roberson Jr. and Frances M. Roberson Endowed Fund for North Carolina Art. Photography is by Peter Paul Geoffrion. See article on Page 34. ARTICLE INDEX Advertising Directory This index has active links, just click on the Page number and it will take you to that page. Listed in order in which they appear in the paper. DONALD Weber Page 1 - Cover - NC Museum of Art - Lien Truong Page 3 - Ella Walton Richardson Fine Art Page 2 - Article Index, Advertising Directory, Contact Info, Links to blogs, and Carolina Arts site Page 4 - Linda Fantuzzo / City Gallery at Waterfront Park Page 4 - Editorial Commentary & Charleston Artist Guild Page 5 - Wells Gallery & Halsey McCallum Studio Page 5 - Ella Walton Richardson Fine Art & Robert Lange Studios “Italian Sojourn” Page 6 - Kathryn Whitaker Page 6 - Meyer Vogl Gallery & City of North Charleston Page 7 - Emerge SC, Helena Fox Fine Art, Corrigan Gallery, Halsey-McCallum Studio, Page 8 - Art League of Hilton Head Reception March 6th 5-8 pm | Painting Demonstration March 7th 2-5 pm Rhett Thurman, Anglin Smith Fine Art, Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art, Page 10 - Coastal Discovery Museum, Society of Bluffton Artists & Clemson University / Sikes Hall The Wells Gallery at the Sanctuary & Saul Alexander Foundation Gallery Exhibition through April 1st, 2020 Page 12 - Clemson University / Sikes Hall cont. -

Darco Progress Talks Agribusiness Future the Palmetto Agribusiness Development

CIVIL WAR EXHIBIT 1B 2A OPINION 4A OBITUARIES 7A SPORTS 2B PUZZLES 4B BOOKINGS 7B CLASSIFIEDS QUOTE ‘All that is necessary for the triumph of evil is that good men do nothing.’ EDMUND BURKE Vol. 142, No. 39 NTWO SECTIONS e• 16 PAGwES s&PreESTAs BLISHsED 1874 75¢ OCTOBER 5, 2016 Darlington, S.C. WWW.NEWSANDPRESS.NET DarCo Progress talks agribusiness future the Palmetto AgriBusiness development. stant market demand for food By Samantha Lyles Staff Writer Council spoke to Progress mem - Shuler said that agribusiness and the prohibitive cost of ship - [email protected] bers about the need for east represents a $42 billion a year ping food from other countries The potential role of food coast food processing plants and industry in South Carolina, with or even from the west coast of processing took center stage last the potential financial gains $18 billion from forestry and the United States. Shuler noted week as Darlington County Darlington County could reap $24 billion from agriculture. that it costs on average about Progress, the private business by focusing on this industry. Breaking it down further, he $6,000 to transport a container arm of the public / private eco - “Darlington County is just added that 48-percent of that of food grown in California to nomic development partnership right for agribusiness,” said $24 billion comes from the the east coast, and said that between Darlington County and Shuler, noting the county's rich poultry industry alone. costs would be notably lower if local business and industry, history with farming and agri - Food processing plants could farming states like South held its 2016 annual meeting culture, and encouraging all provide a stable financial Carolina had more food pro - September 29 at the SiMT con - present to keep “top of the mind anchor for Darlington County, cessing and packaging plants. -

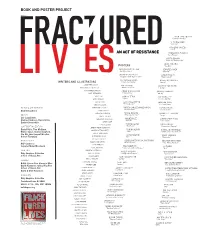

Book and Poster Project an Act of Resistance

BOOK AND POSTER PROJECT IGOR LANGSHTEYN “Secret Formulas” SEYOUNG PARK “Hard Hat” CAROLINA CAICEDO “Shell” AN ACT OF RESISTANCE FRANCESCA TODISCO “Up in Flames” CURTIS BROWN “Not in my Fracking City” WOW JUN CHOI POSTERS “Cracking” SAM VAN DEN TILLAAR JENNIFER CHEN “Fracktured Lives” “Dripping” ANDREW CASTRUCCI LINA FORSETH “Diagram: Rude Algae of Time” “Water Faucet” ALEXANDRA ROJAS NICHOLAS PRINCIPE WRITERS AND ILLUSTRATORS “Protect Your Mother” “Money” SARAH FERGUSON HYE OK ROW ANDREW CASTRUCCI ANN-SARGENT WOOSTER “Water Life Blood” “F-Bomb” KATHARINE DAWSON ANDREW CASTRUCCI MICHAEL HAFFELY MIKE BERNHARD “Empire State” “Liberty” YOKO ONO CAMILO TENSI JUN YOUNG LEE SEAN LENNON “Pipes” “No Fracking Way” AKIRA OHISO IGOR LANGSHTEYN MORGAN SOBEL “7 Deadly Sins” CRAIG STEVENS “Scull and Bones” EDITOR & ART DIRECTOR MARIANNE SOISALO KAREN CANALES MALDONADO JAYPON CHUNG “Bottled Water” Andrew Castrucci TONY PINOTTI “Life Fracktured” CARLO MCCORMICK MARIO NEGRINI GABRIELLE LARRORY DESIGN “This Land is Ours” “Drops” CAROL FRENCH Igor Langshteyn, TERESA WINCHESTER ANDREW LEE CHRISTOPHER FOXX Andrew Castrucci, Daniel Velle, “Drill Bit” “The Thinker” Daniel Giovanniello GERRI KANE TOM MCGLYNN TOM MCGLYNN KHI JOHNSON CONTRIBUTING EDITORS “Red Earth” “Government Warning” JEREMY WEIR ALDERSON Daniel Velle, Tom McGlynn, SANDRA STEINGRABER TOM MCGLYNN DANIEL GIOVANNIELLO Walter Sipser, Dennis Crawford, “Mob” “Make Sure to Put One On” ANTON VAN DALEN Jim Wu, Ann-Sargent Wooster, SOFIA NEGRINI ALEXANDRA ROJAS DAVID SANDLIN Robert Flemming “No” “Frackicide” -

California State University, Northridge Shepard Fairey

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE SHEPARD FAIREY AND STREET ART AS POLITICAL PROPAGANDA A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts in Art, Art History by Andrea Newell August 2016 Copyright by Andrea Newell 2016 ii The thesis of Andrea Newell is approved: _______________________________________________ ____________ Meiqin Wang, Ph.D. Date _______________________________________________ ____________ Owen Doonan, Ph.D. Date _______________________________________________ ____________ Mario Ontiveros, Ph.D., Chair Date California State University, Northridge iii Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my thesis advisor Dr. Mario Ontiveros of the Art Department at California State University, Northridge. He always challenged me in a way that brought out my best work. Our countless conversations pushed me to develop a deeper and more comprehensive understanding of my research and writing as well as my knowledge of theory, art practices and the complexities of the art world. He consistently allowed this paper to be my own work, but guided me whenever he thought I needed it, my sincerest thanks. My deepest gratitude also goes out to my committee, Dr. Meiqin Wang and Dr. Owen Doonan, whose thoughtful comments, kind words, and assurances helped this research project come to fruition. Without their passionate participation and input, this thesis could not have been successfully completed. I would also like to acknowledge Dr. Peri Klemm for her constant support beyond this thesis and her eagerness to provide growth opportunities in my career as an art historian and educator. I am gratefully indebted to my co-worker Jessica O’Dowd for our numerous conversations and her input as both a friend and colleague. -

Augmentation As Art Intervention: the New Means of Art Intervention Through Mixed Reality by Runzhou Ye

Augmentation as Art Intervention: The New Means of Art Intervention Through Mixed Reality by Runzhou Ye M.Arch. University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 B.Arch. Chongqing University, 2015 Submitted to the Department of Architecture in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Art, Culture and Technology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology JUNE 2019 © 2019 Runzhou Ye. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: Department of Architecture May 10, 2019 Certified by: Azra Akšamija Associate Professor of Art, Culture and Technology Accepted by: Nasser Rabbat Aga Khan Professor Chair of the Department Committee on Graduate Students 1 COMMITTEE Thesis Supervisor: Azra Akšamija, PhD Associate Professor of Art, Culture and Technology Thesis Reader: Tobias Putrih Lecturer of Art, Culture and Technology Thesis Reader: James G. Paradis, PhD Robert M. Metcalfe Professor of Writing and Comparative Media Studies 2 Augmentation as Art Intervention: The New Means of Art Intervention Through Mixed Reality by Runzhou Ye Submitted to the Department of Architecture on May 10, 2019 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Art, Culture and Technology. ABSTRACT This thesis explores an emerging art form—mixed reality art—the new opportunities, changes, and challenges it brings to art intervention. Currently, mixed reality art is in its early stage of development, and there is relatively little scholarship about this subject. -

EXHIBITIONS at 583 BROADWAY Linda Burgess Helen Oji Bruce Charlesworth James Poag Michael Cook Katherine Porter Languag�

The New Museum of Contemporary Art New York TenthAnniversary 1977-1987 Library of Congress Calalogue Card Number: 87-42690 Copyright© 1987 The New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York. All Rights Reserved ISBN 0-915557-57-6 Plato's Cave, Remo Campopiano DESIGN: Victor Weaver, Ron Puhalsk.i'&? Associates, Inc. PRINTING: Prevton Offset Printing, Inc. INK: Harvey Brice, Superior Ink. PAPER: Sam Jablow, Marquardt and Co. 3 2 FROM THE PRESIDENT FROM THE DIRECTOR When Marcia Tu cker,our director,founded The New Museum of Contemporary Art, what were Perhaps the most important question The New Museum posed for itself at the beginning, ten the gambler's odds that it would live to celebrate its decennial? I think your average horse player would years ago, was "how can this museum be different?" In the ten years since, the answer to that question have made it a thirty-to-one shot. Marcia herself will, no doubt, dispute that statement, saying that it has changed, although the question has not. In 1977, contemporary art was altogether out of favor, and was the right idea at the right time in the right place, destined to succe�d. In any case, it did. And here it most of the major museums in the country had all but ceased innovative programming in that area. It is having its Te nth Anniversary. was a time when alternative spaces and institutes of contemporary art flourished: without them, the art And what are the odds that by now it would have its own premises, including capacious, of our own time might have.remained invisible in the not-for-profitcultural arena. -

San Diego Public

San Diego Public Art A standard lament in the visual arts community is that San Diego is fated to be a perpetual Jersey-on-the-Pacific, with art remaining the odd duck out in a region known for its theatre and physical culture. The artists tend to blame this on the weather, without considering that the problem may be their art. San Diego has beautiful light, and people are outdoors enjoying it. For art to be an integral part of the regional culture, it needs to follow the people outdoors. To a remarkable extent this has already occurred: art's outside in San Diego, thanks to community action, private foundations, and city art programs. But the region also has a history of civic controversies over public art: several high-profile proposals have crashed and burned, and in a few cases installed work was removed. Sometimes the fault seemed to lie as much with the artist as the unhappy public. Artists and audience alike need to learn: good art is hard, good public art harder. And even the controversy itself needs to be put into perspective: about the proposed Statue of Liberty, the New York Times opined that "no true patriot can countenance any such expenditures for bronze females in the present state of our finances." Parisians hated the Eiffel Tower. Veterans hated the Vietnam Wall. To date most media coverage of San Diego public art has been event- driven, focused on proposals, installations, and any ensuing controversies. What's been missing is a directory of public art: something that not only helps interested viewers find the community gems and learn more about them, but also shows just how much good public art there already is. -

Vol. 25, No. 3 March 2021 You Can’T Buy It

ABSOLUTELY FREE Vol. 25, No. 3 March 2021 You Can’t Buy It Work by Aria Crumlick Wible is part of the exhibit Anything Goes!, a showcase of the best of Art League of Hilton Head members’ works with no limitations. The exhibit will be on view from March 9 through April 3, 2021, at the Art League Gallery, located inside the Arts Center of Coastal Carolina, Hilton Head Island, SC. See article on Page 9. ARTICLE INDEX Advertising Directory This index has active links, just click on the Page number and it will take you to that page. Listed in order in which they appear in the paper. Page 1 - Cover - Art League of Hilton Head - Aria Crumlick Wible Page 3 - Art League of Hilton Head Page 2 - Article Index, Advertising Directory, Contact Info, Links to blogs, and Carolina Arts site Page 4 - Halsey McCallum Studio Page 3 - City of Charleston / City Gallery & Charleston Artist Guild Page 4 - Editorial Commentary, Charleston Artist Guild cont. & City of North Charleston Page 5 - Deane V. Bowers Art & Wells Gallery Page 5 - City of North Charleston cont., Meyer Vogl Gallery & Anglin Smith Fine Art Page 6 - Anglin Smith Fine Art cont. & Lowcountry Artists Gallery Page 6 - Whimsy Joy by Roz, Pastel Society of South Carolina & Public Works Art Center Page 8 - A Book Review: Still Time On Pye Pond by Danielle Fontaine Page 7 - Emerge SC, Helena Fox Fine Art, Corrigan Gallery, Halsey-McCallum Studio, Page 9 - Art League of Hilton Head, Society of Bluffton Artists & Bluffton Artisan Market Page 10 - Inside the Artist’s Studio - Alice Ballard Rhett Thurman, Anglin Smith Fine Art, Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art, Page 11 - Inside the Artist’s Studio - Alice Ballard cont. -

Texas Highways Spring Events Calendar

SPRING 2019 MARCH • APRIL • MAY EVENTSC A L E N DA R FESTIVALS, CONCERTS, EXHIBITS, PARADES, AND ALL THINGS FUN IN TEXAS! SNAPSHOT Butterfly Festival See more inside... EVENTS SPRING 2019 spent more than 25 years banking that national and regional acts (past perform- Field of other Texans feel the same way. Found- ers include Jimmy Eat World, Spoon, and ed in 1993 as a small community event, Kool & The Gang), the event hosts eight Dreams the three-day music and arts festival stages, family-friendly events, the food- ady Bird Johnson once said, “My takes its inspiration from Texas’ colorful ie-friendly WF! Eats, a battle of the heart found its home long ago wildflower season, which puts on a bands, and more. The 2019 event takes in the beauty, mystery, order, stately show each spring. Now, more place May 17-19 at Richardson’s Gatlyn and disorder of the flowering than 25 years in, Wildflower! has grown Park. For more information, including Learth.” The folks at Wildflower! Arts to become one of the most anticipated this year’s lineup, call 972-744-4580 and Music Festival in Richmond have events in North Texas. In addition to or visit wildflowerfestival.com. ON THE COVER UP IN THE AIR The bats may be Austin’s preferred winged creature, but in Wimberley, it’s the butterfly that’s basking in the spotlight. Every April, the town cele- brates life with the release of thousands of butterflies and fanfare to boot at the annual Butterfly Festival, hosted by the EmilyAnn Theater and Gar- dens.