John Cage Was a Bastard!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

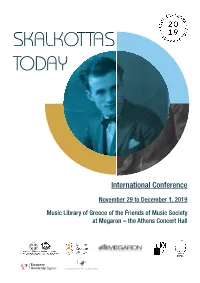

SKALKOTTAS Program 148X21

International Conference Program NOVEMBER 29 TO DECEMBER 1, 2019 Music Library of Greece of the Friends of Music Society at Megaron – the Athens Concert Hall Organised by the Music Library of Greece “Lilian Voudouri” of the Friends of Music Society, Megaron—The Athens Concert Hall, Athens State Orchestra, Greek Composer’s Union, Foundation of Emilios Chourmouzios—Marika Papaioannou, and European University of Cyprus. With the support of the Ministry of Culture and Sports, General Directorate of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage, Directorate of Modern Cultural Heritage The conference is held under the auspices of the International Musicological Society (IMS) and the Hellenic Musicological Society It is with great pleasure and anticipa- compositional technique. This confer- tion that this conference is taking place ence will give a chance to musicolo- Organizing Committee: Foreword .................................... 3 in the context of “2019 - Skalkottas gists and musicians to present their Thanassis Apostolopoulos Year”. The conference is dedicated to research on Skalkottas and his environ- the life and works of Nikos Skalkottas ment. It is also happening Today, one Alexandros Charkiolakis Schedule .................................... 4 (1904-1949), one of the most important year after the Aimilios Chourmouzios- Titos Gouvelis Greek composers of the twentieth cen- Marika Papaioannou Foundation depos- tury, on the occasion of the 70th anni- ited the composer’s archive at the Music Petros Fragistas Abstracts .................................... 9 versary of his death and the deposition Library of Greece “Lilian Voudouri” of Vera Kriezi of his Archive at the Music Library of The Friends of Music Society to keep Greece “Lilian Voudouri” of The Friends safe, document and make it available for Martin Krithara Biographies ............................. -

Twelve-Tone Technique and Modality in Nikos Skalkottas's Music

IMS-RASMB, Series Musicologica Balcanica 1.1, 2020. e-ISSN: 2654-248X Twelve-tone Technique and Modality in Nikos Skalkottas’s Music by George Zervos DOI: https://doi.org/10.26262/smb.v1i1.7754 ©2020 The Author. This is an open access article under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution NonCom- mercial NoDerivatives International 4.0 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided that the articles is properly cited, the use is non-commercial and no modifications or adaptations are made. Zervos, Twelve-Tone Technique and Modality… Twelve-Tone Technique and Modality in Nikos Skalkottas’s Music George Zervos Abstract In Nikos Skalkottas’s compositional output, the use of modality through the folk tra- dition, is not limited to some of the tonal works, such as the 36 Greek Dances, but it also extends to the strictly or freely twelve-tone works; indeed, this is the case throughout the composer’s creative life. Given the changing character of the ways in which this folk tradition is incorporated into a twelve-tone and, in general, an atonal environ- ment, we chose two works from different periods, in order to show the modes in which the composer manages to connect the various aspects of the twelve-tone with modal- ity: these are the first movement of Sonatina No.2 for violin and piano (1929), and the first movement of Petite Suite No.1 for solo violin and piano (1946). More specifically, in the first case, we will show the ways in which the prime row is transformed into a diatonic- chromatic-like modality, and in the second case we will discuss the function of the combination of two complementary hexachords through which two sets are produced. -

Perceptual Interactions of Pitch and Timbre: an Experimental Study on Pitch-Interval Recognition with Analytical Applications

Perceptual interactions of pitch and timbre: An experimental study on pitch-interval recognition with analytical applications SARAH GATES Music Theory Area Department of Music Research Schulich School of Music McGill University Montréal • Quebec • Canada August 2015 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts. Copyright © 2015 • Sarah Gates Contents List of Figures v List of Tables vi List of Examples vii Abstract ix Résumé xi Acknowledgements xiii Author Contributions xiv Introduction 1 Pitch, Timbre and their Interaction • Klangfarbenmelodie • Goals of the Current Project 1 Literature Review 7 Pitch-Timbre Interactions • Unanswered Questions • Resulting Goals and Hypotheses • Pitch-Interval Recognition 2 Experimental Investigation 19 2.1 Aims and Hypotheses of Current Experiment 19 2.2 Experiment 1: Timbre Selection on the Basis of Dissimilarity 20 A. Rationale 20 B. Methods 21 Participants • Stimuli • Apparatus • Procedure C. Results 23 2.3 Experiment 2: Interval Identification 26 A. Rationale 26 i B. Method 26 Participants • Stimuli • Apparatus • Procedure • Evaluation of Trials • Speech Errors and Evaluation Method C. Results 37 Accuracy • Response Time D. Discussion 51 2.4 Conclusions and Future Directions 55 3 Theoretical Investigation 58 3.1 Introduction 58 3.2 Auditory Scene Analysis 59 3.3 Carter Duets and Klangfarbenmelodie 62 Esprit Rude/Esprit Doux • Carter and Klangfarbenmelodie: Examples with Timbral Dissimilarity • Conclusions about Carter 3.4 Webern and Klangfarbenmelodie in Quartet op. 22 and Concerto op 24 83 Quartet op. 22 • Klangfarbenmelodie in Webern’s Concerto op. 24, mvt II: Timbre’s effect on Motivic and Formal Boundaries 3.5 Closing Remarks 110 4 Conclusions and Future Directions 112 Appendix 117 A.1,3,5,7,9,11,13 Confusion Matrices for each Timbre Pair A.2,4,6,8,10,12,14 Confusion Matrices by Direction for each Timbre Pair B.1 Response Times for Unisons by Timbre Pair References 122 ii List of Figures Fig. -

The Order of Numbers in the Second Viennese School of Music

The order of numbers in the Second Viennese School of Music Carlota Sim˜oes Department of Mathematics University of Coimbra Portugal Mathematics and Music seem nowadays independent areas of knowledge. Nevertheless, strong connections exist between them since ancient times. Twentieth-century music is no exception, since in many aspects it admits an obvious mathematical formalization. In this article some twelve-tone music rules, as created by Schoenberg, are presented and translated into math- ematics. The representation obtained is used as a tool in the analysis of some compositions by Schoenberg, Berg, Webern (the Second Viennese School) and also by Milton Babbitt (a contemporary composer born in 1916). The Second Viennese School of Music The 12-tone music was condemned by the Nazis (and forbidden in the occupied Europe) because its author was a Jew; by the Stalinists for having a bourgeois cosmopolitan formalism; by the public for being different from everything else. Roland de Cand´e[2] Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951) was born in Vienna, in a Jewish family. He lived several years in Vienna and in Berlin. In 1933, forced to leave the Academy of Arts of Berlin, he moved to Paris and short after to the United States. He lived in Los Angeles from 1934 until the end of his life. In 1923 Schoenberg presented the twelve-tone music together with a new composition method, also adopted by Alban Berg (1885-1935) and Anton Webern (1883-1945), his students since 1904. The three composers were so closely associated that they became known as the Second Viennese School of Music. -

The William Paterson University Department of Music Presents New

The William Paterson University Department of Music presents New Music Series Peter Jarvis, director Featuring the Velez / Jarvis Duo, Judith Bettina & James Goldsworthy, Daniel Lippel and the William Paterson University Percussion Ensemble Monday, October 17, 2016, 7:00 PM Shea Center for the Performing Arts Program Mundus Canis (1997) George Crumb Five Humoresques for Guitar and Percussion 1. “Tammy” 2. “Fritzi” 3. “Heidel” 4. “Emma‐Jean” 5. “Yoda” Phonemena (1975) Milton Babbitt For Voice and Electronics Judith Bettina, voice Phonemena (1969) Milton Babbitt For Voice and Piano Judith Bettina, voice James Goldsworthy, Piano Penance Creek (2016) * Glen Velez For Frame Drums and Drum Set Glen Velez – Frame Drums Peter Jarvis – Drum Set Themes and Improvisations Peter Jarvis For open Ensemble Glen Velez & Peter Jarvis Controlled Improvisation Number 4, Opus 48 (2016) * Peter Jarvis For Frame Drums and Drum Set Glen Velez – Frame Drums Peter Jarvis – Drum Set Aria (1958) John Cage For a Voice of any Range Judith Bettina May Rain (1941) Lou Harrison For Soprano, Piano and Tam‐tam Elsa Gidlow Judith Bettina, James Goldsworthy, Peter Jarvis Ostinato Mezzo Forte, Opus 51 (2016) * Peter Jarvis For Percussion Band Evan Chertok, David Endean, Greg Fredric, Jesse Gerbasi Daniel Lucci, Elise Macloon Sean Dello Monaco – Drum Set * = World Premiere Program Notes Mundus Canis: George Crumb George Crumb’s Mundus Canis came about in 1997 when he wanted to write a solo guitar piece for his friend David Starobin that would be a musical homage to the lineage of Crumb family dogs. He explains, “It occurred to me that the feline species has been disproportionately memorialized in music and I wanted to help redress the balance.” Crumb calls the work “a suite of five canis humoresques” with a character study of each dog implied through the music. -

John Cage's Entanglement with the Ideas Of

JOHN CAGE’S ENTANGLEMENT WITH THE IDEAS OF COOMARASWAMY Edward James Crooks PhD University of York Music July 2011 John Cage’s Entanglement with the Ideas of Coomaraswamy by Edward Crooks Abstract The American composer John Cage was famous for the expansiveness of his thought. In particular, his borrowings from ‘Oriental philosophy’ have directed the critical and popular reception of his works. But what is the reality of such claims? In the twenty years since his death, Cage scholars have started to discover the significant gap between Cage’s presentation of theories he claimed he borrowed from India, China, and Japan, and the presentation of the same theories in the sources he referenced. The present study delves into the circumstances and contexts of Cage’s Asian influences, specifically as related to Cage’s borrowings from the British-Ceylonese art historian and metaphysician Ananda K. Coomaraswamy. In addition, Cage’s friendship with the Jungian mythologist Joseph Campbell is detailed, as are Cage’s borrowings from the theories of Jung. Particular attention is paid to the conservative ideology integral to the theories of all three thinkers. After a new analysis of the life and work of Coomaraswamy, the investigation focuses on the metaphysics of Coomaraswamy’s philosophy of art. The phrase ‘art is the imitation of nature in her manner of operation’ opens the doors to a wide- ranging exploration of the mimesis of intelligible and sensible forms. Comparing Coomaraswamy’s ‘Traditional’ idealism to Cage’s radical epistemological realism demonstrates the extent of the lack of congruity between the two thinkers. In a second chapter on Coomaraswamy, the extent of the differences between Cage and Coomaraswamy are revealed through investigating their differing approaches to rasa , the Renaissance, tradition, ‘art and life’, and museums. -

View Becomes New." Anton Webern to Arnold Schoenberg, November, 25, 1927

J & J LUBRANO MUSIC ANTIQUARIANS Catalogue 74 The Collection of Jacob Lateiner Part VI ARNOLD SCHOENBERG 1874-1951 ALBAN BERG 1885-1935 ANTON WEBERN 1883-1945 6 Waterford Way, Syosset NY 11791 USA Telephone 561-922-2192 [email protected] www.lubranomusic.com CONDITIONS OF SALE Please order by catalogue name (or number) and either item number and title or inventory number (found in parentheses preceding each item’s price). To avoid disappointment, we suggest either an e-mail or telephone call to reserve items of special interest. Orders may also be placed through our secure website by entering the inventory numbers of desired items in the SEARCH box at the upper left of our homepage. Libraries may receive deferred billing upon request. Prices in this catalogue are net. Postage and insurance are additional. An 8.625% sales tax will be added to the invoices of New York State residents. International customers are asked to kindly remit in U.S. funds (drawn on a U.S. bank), by international money order, by electronic funds transfer (EFT) or automated clearing house (ACH) payment, inclusive of all bank charges. If remitting by EFT, please send payment to: TD Bank, N.A., Wilmington, DE ABA 0311-0126-6, SWIFT NRTHUS33, Account 4282381923 If remitting by ACH, please send payment to: TD Bank, 6340 Northern Boulevard, East Norwich, NY 11732 USA ABA 026013673, Account 4282381923 All items remain the property of J & J Lubrano Music Antiquarians LLC until paid for in full. Fine Items & Collections Purchased Please visit our website at www.lubranomusic.com where you will find full descriptions and illustrations of all items Members Antiquarians Booksellers’ Association of America International League of Antiquarian Booksellers Professional Autograph Dealers’ Association Music Library Association American Musicological Society Society of Dance History Scholars &c. -

Study Guide: Graduate Placement Examination in Music History

GRADUATE PLACEMENT EXAMINATION IN MUSIC HISTORY STUDY GUIDE The Graduate Placement Examination in Music History is designed to ascertain whether incoming graduate students have a knowledge of music history commensurate with an undergraduate degree in music. It is typically offered prior to the first day of classes each semester. Students are asked to identify important historical figures, define important terms, compose a brief essay, and draw conclusions from a musical score. Some knowledge of musical traditions beyond the Western/European classical traditions, including topics such as “world music,” “folk music,” and “popular music,” is also expected. The ninety-minute examination comprises the following sections: 1. identification of composers and schools of composition (choose from a list provided during the exam); worth 25 points, allow approximately 20 minutes 2. identification of terms (choose from a list provided during the exam); worth 25 points, allow approximately 20 minutes 3. essay (choose a topic from a list provided during the exam); worth 30 points, allow approximately 30 minutes 4. score identification, including: historical period and approximate date of composition; genre, its important stylistic features, and how/where they can be seen in the piece; and the name of the likely composer; worth 20 points, allow approximately 20 minutes. This study guide provides lists, organized by historical era (with approximate dates), of major figures, genres, and terms from music history. They are not necessarily complete or comprehensive lists of items that will appear on the test. For further review, the faculty recommend consulting the textbook (and accompanying scores and recordings) used in the undergraduate core music history sequence in the Department of Music. -

Academiccatalog 2017.Pdf

New England Conservatory Founded 1867 290 Huntington Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02115 necmusic.edu (617) 585-1100 Office of Admissions (617) 585-1101 Office of the President (617) 585-1200 Office of the Provost (617) 585-1305 Office of Student Services (617) 585-1310 Office of Financial Aid (617) 585-1110 Business Office (617) 585-1220 Fax (617) 262-0500 New England Conservatory is accredited by the New England Association of Schools and Colleges. New England Conservatory does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, age, national or ethnic origin, sexual orientation, physical or mental disability, genetic make-up, or veteran status in the administration of its educational policies, admission policies, employment policies, scholarship and loan programs or other Conservatory-sponsored activities. For more information, see the Policy Sections found in the NEC Student Handbook and Employee Handbook. Edited by Suzanne Hegland, June 2016. #e information herein is subject to change and amendment without notice. Table of Contents 2-3 College Administrative Personnel 4-9 College Faculty 10-11 Academic Calendar 13-57 Academic Regulations and Information 59-61 Health Services and Residence Hall Information 63-69 Financial Information 71-85 Undergraduate Programs of Study Bachelor of Music Undergraduate Diploma Undergraduate Minors (Bachelor of Music) 87 Music-in-Education Concentration 89-105 Graduate Programs of Study Master of Music Vocal Pedagogy Concentration Graduate Diploma Professional String Quartet Training Program Professional -

Conceiving Musical Transdialection

Conceiving Musical Transdialection By Richard Beaudoin, Harvard University and Joseph Moore, Amherst College Abstract: We illuminate the wandering notion of a musical transcription by reflecting on the various ways “transcription” and its cognates have been used in musical discourse, and by examining some notable 20th century transcriptions of J. S. Bach, which became increasingly loose through the decades. At root, musical transcription aims at preservation, but, as we bring out, exactly which musical ingredients are preserved across which transformations varies from transcriptional project to transcriptional project. We defend as intelligible one very interesting such project—we call it “transdialection”—by exploring an analogy with poetic translation, and by directly taking on some natural objections to it. We conclude that certain controversial transcriptions are justifiably and usefully so-called. 1 0. Transcription Traduced While it may not surprise you to learn that the first bit of music above is the opening of a chorale prelude by Baroque master, J. S. Bach, who would guess that the second bit is a so-called transcription of it? But it is—it’s a transcription by the contemporary British composer, Michael Finnissy. The two passages look very different from one another, even to those of us who don’t read music. And hearing the pieces will do little to dispel the shock, for here we have bits of music that seem worlds apart in their melodic makeup, harmonic content and rhythmic complexity. It’s a far cry from Bach’s steady tonality to Finnissy’s floating, tangled lines—a sonic texture in which, as one critic put it, real music is “mostly thrown into a seething undigested, unimagined heap of dyslexic clusters of multiple key- and time-proportions, as intricately enmeshed in the fetishism of the written notation as those 2 with notes derived from number-magic.”1 We’re more sympathetic to Finnissy’s music. -

Surrealism and Music in France, 1924-1952: Interdisciplinary and International Contexts Friday 8 June 2018: Senate House, University of London

Surrealism and music in France, 1924-1952: interdisciplinary and international contexts Friday 8 June 2018: Senate House, University of London 9.30 Registration 9.45-10.00 Welcome and introductions 10.00-11.00 Session 1: Olivier Messiaen and surrealism (chair: Caroline Potter) Elizabeth Benjamin (Coventry University): ‘The Sound(s) of Surrealism: on the Musicality of Painting’ Robert Sholl (Royal Academy of Music/University of West London): ‘Messiaen and Surrealism: ethnography and the poetics of excess’ 11.00-11.30 Coffee break 11.30-13.00 Session 2: Surrealism, ethnomusicology and music (chair: Edward Campbell) Renée Altergott (Princeton University): ‘Towards Automatism: Ethnomusicology, Surrealism, and the Question of Technology’ Caroline Potter (IMLR, School of Advanced Study, University of London): ‘L’Art magique: the surreal incantations of Boulez, Jolivet and Messiaen’ Edmund Mendelssohn (University of California Berkeley): ‘Sonic Purity Between Breton and Varèse’ 13.00 Lunch (provided) 13.45 Keynote (chair: Caroline Potter) Sébastien Arfouilloux (Université Grenoble-Alpes) : ‘Présences du surréalisme dans la création musicale’ 14.45-15.45 Session 3: Surrealism and music analysis (chair: Caroline Rae) Henri Gonnard (Université de Tours): ‘L’Enfant et les sortilèges (1925) de Maurice Ravel et le surréalisme : l’exemple du préambule féerique de la 2e partie’ James Donaldson (McGill University): ‘Poulenc, Fifth Relations, and a Semiotic Approach to the Musical Surreal’ 15.45-16.15 Coffee break 16.15-17.15 Session 4: Surrealism and musical innovation (chair: Paul Archbold) Caroline Rae (Cardiff University): ‘André Jolivet, Antonin Artaud and Alejo Carpentier: Redefining the Surreal’ Edward Campbell (Aberdeen University): ‘Boulez’s Le Marteau as Assemblage of the Surreal’ 17.15 Concluding remarks 17.45-18.45 Concert: Alexander Soares, Chancellor’s Hall Programme André Jolivet: Piano Sonata no. -

Melody on the Threshold in Spectral Music *

Melody on the Threshold in Spectral Music * James Donaldson NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: hps://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.21.27.2/mto.21.27.2.donaldson.php KEYWORDS: spectralism, melody, liminal, Bergson, Gérard Grisey, Claude Vivier, Georg Friedrich Haas, Kaija Saariaho ABSTRACT: This article explores the expressive and formal role of melody in spectral and “post- spectral” music. I propose that melody can function within a spectral aesthetic, expanding the project of relating unfamiliar musical parameters to “liquidate frozen categories” (Grisey 2008 [1982], 45). Accordingly, I show how melody can shift in and out of focus relative to other musical elements. I adopt Grisey’s use of the terms differential and liminal to describe relationships between two musical elements: differential refers to the process between distinct elements whereas liminal describes moments of ambiguity between two elements. I apply these principles to Grisey’s Prologue (1976), Vivier’s Zipangu (1977), Haas’s de terrae fine (2001), and Saariaho’s Sept Papillons (2000). Received February 2020 Volume 27, Number 2, June 2021 Copyright © 2021 Society for Music Theory [1.1] In the writings by figures associated with the spectral movement, which emerged in early 1970s Paris, references to melody are rare. As the group focused on the acoustic properties of sound, this is perhaps unsurprising. Nevertheless, the few appearances can be divided into two categories. First—and representative of broadly scientizing motivations in post-war post-tonal music—is the dismissal of melody as an anachronism. Gérard Grisey’s 1984 “La musique, le devenir des sons” is representative: with a rhetoric of founding a new style, he is dismissive of past practices, specifically that there is no “matériau de base” such as “melodic cells” (Grisey 2008 [1978], 27).