Forest Resources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wyantenock State Forest, Cornwall

Wyantenock State Forest Overview Ü Location: Cornwall, Kent, Warren Description: 4,083 total acres. Note: This map depicts an approximation of property boundaries. Please obey all postings. Symbols: Salmon River State Forest UV4 Sharon Cornwall Goshen ¤£7 Kent Litchfield Warren ¤£202 Washington Morris Map Date: 11/24/2015; Ortho 2012 4band NAIP 6,000 3,000 0 6,000 Feet State of Connecticut - Department of Energy & Environmental Protection - 79 Elm St. - Hartford, CT 06106 - www.ct.gov/deep Wyantenock State Forest Cornwall North Ü Location: Coltsfood Mountain Block, Cornwall Description: 4,083 total acres. Mixed conifer and hardwoods. Access: Park in roadside pull-offs along Route 4 in Cornwall. Note: This map depicts an approximation of property boundaries. Please obey all postings. Symbols: Salmon River State Forest 500 foot buffer V d a 7 R p l d l e R am 4 e t p SV w y u m S a le o w p r R S p t D R le Po es d pp W Po S d t R a t p e m H a w w S y e 4 l p p o 4 P SV d R k o o r B 4 R e o c y u a w t rn H e u e U 7 F t ta S S H w U d S y R 7 H SV4 y w e l y l 7 a V Sta B te H ro wy 4 o k R E v d d e R r 7 e r ¤£ s e t v d i H R d d R t i R R l n d l r e e n R R v K i d d w e R R o l t r t e s v y i a 7 e R d l d C y d R R u t w n H D w e o S d l l K U R o n H B w u t o r a lw t o y e o e r d l G 7 Ln d ¤£ u D Map Date: 6/28/2017; Ortho 2016 NAIP 1,600 800 0 1,600 Feet State of Connecticut - Department of Energy & Environmental Protection - 79 Elm St. -

Regional Recreational Trail Map

Northwest Hills Council of Governments Regional Recreational Trail Map 03_J 01_F 02_A 02_A 02_A North Canaan 01_C 05_A 03_C 05_C Norfolk 04_C Hartland 02_B 03_B 03_A Colebrook 05_B 06_C 04_A 01_F Salisbury 03_I 01_D 04_B 03_H 01_B Canaan 03_G 03_D 06_A 07_E 08_B 07_F 08_A Barkhamsted 08_C 01_A 06_B 07_A Winchester 09_E 11_I 07_C 09_H 09_D 07_B 09_H 11_F 10_C 11_B 07_H 09_G 10_D 07_G 09_E 09_E 12_G 12_B 09_B 10_E 10_B 12_A 13_C 10_G 13_B Sharon 09_E 10_A Goshen 09_E 11_J Cornwall 13_G 12_F 09_I 13_E 11_C New Hartford 09_K 12_H 09_E 10_F 09_C Torrington 11_D 13_A 11_G 11_E 13_F 12_C 13_D 09_E 11_A 11_H 09_A 09_E 09_J 11_G 10_H 18_E 17_E 14_E 14_J Burlington 16_A 14_G 14_I 17_C 17_D 17_B 14_F 16_F 18_A 18_B Litchfield Harwinton 15_A 18_A 14_C Warren 18_F 16_H 16_E 17_G 14_L 17_A 16_C 16_H 17_F 15_C 16_H 17_H 15_B Kent 16_K 18_D 15_E 14_K 15_D 16_G 16_J 16_I 18_C 14_M 16_B 19_B 14_A 20_D 20_D 14_B 16_D 14_O 20_D 19_E 20_A 14_P 19_A Morris 14_N 20_B 20_C 19_D Town Index Code Trail System Town Index Code Trail System Cornwall 10_A Ballyhack Warren 15_A Mattatuck Trail Cornwall 10_B Gold's Pines/Day Preserve Warren 15_B Above All State Park Cornwall 10_C Hart Farm/Cherry Hill Warren 15_C Dorothy Maier Preserve Washington Town Index Code Trail System Cornwall 10_D Rattlesnake Preserve Warren 15_D Wyantenock State Forest Salisbury 01_A Sycamore Field Warren 15_E Coords Preserve Cornwall 10_E Welles Preserve Salisbury 01_B Dark Hollow Litchfield 16_A Stillman-Danaher Preserve Cornwall 10_F Mohawk Mountain Salisbury 01_C Schlesinger Bird Preserve -

National Register of Historic Places Received JUL 2 5 Isee Inventory

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use omy National Register of Historic Places received JUL 2 5 isee Inventory Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections____________________________________ 1. Name___________________________ historic________N/A____*____________________________________________________ Connecticut State Park and Forest Depression-Era Federal Work Relief and or common Programs Structures Thematic Resource_______________________ 2. Location____________________________ street & number See inventory Forms___________________________-M/Anot for publication city, town______See Inventory Forms _ vicinity of__________________________ state_______Connecticut code 09_____county See Inventory Forms___code " 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district _ X_ public _ X- occupied agriculture museum _ X- building(s) private unoccupied commercial _ X-park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process _ X- Ves: restricted government scientific X thematic being considered - yes: unrestricted industrial transportation group IN/A no military other: 4. Owner of Property Commissionier Stanley Pac name Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection street & number 165 Capitol Avenue city, town___Hartford______________ vicinity of___________state Connecticut -

Integrated Pest Management (Ipm) for Connecticut

Plant Science Day The Annual Samuel W. Johnson Lecture • Short Talks • Demonstrations • Field Experiments • Passport for Kids Pesticide Credits • Century Farm Award • Barn Exhibits Lockwood Farm, Hamden Wednesday, August 3, 2005 XYXYXYXYXYXY History of Lockwood Farm, Hamden Lockwood Farm is a research farm of the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station. Historically, the farm was purchased in 1910 with monies provided by the Lockwood Trust Fund, a private endowment. The original farm was 19.6 acres with a barn and a house. Since then, several adjacent tracts of land were purchased, enlarging the acres to 75.0. The farm is located in the extreme southern portion of the Central Lowland Physiographic Province. This lowland region is underlain by red stratified sandstone and shale of Triassic age from which resistant lava flows project as sharp ridges. One prominent ridge, observed from the farm, is Sleeping Giant Mountain that lies to the north. The mountain is composed of basalt, a dense igneous rock commonly used as a building material and ballast for railroad tracks. The topography of the farm is gently rolling to hilly and was sculpted by the Wisconsin glacier that overrode the area some 10,000 years ago and came to rest in the vicinity of Long Island. A prominent feature of the farm is a large basaltic boulder that was plucked from Sleeping Giant by the advancing glacier and came to rest on the crest of a hillock to the south of the upper barns. From this hillock, Sleeping Giant State Park comes into full view and is a favorite spot for photographers and artists. -

2016 Connecticut Hunting & Trapping Guide

2016 CONNECTICUT HUNTING & TRAPPING Connecticut Department of VISIT OUR WEBSITE Energy & Environmental Protection www.ct.gov/deep/hunting MONARCH® BINOCULARS Built to satisfy the incredible needs of today’s serious outdoorsmen & women, MONARCH binoculars not only bestow the latest in optical innovation upon the passions of its owner, but offer dynamic handling & rugged performance for virtually any hunting situation. MONARCH® RIFLESCOPES Bright, clear, precise, rugged - just a few of the attributes knowledgeable hunters commonly use to describe Nikon® riflescopes. Nikon® is determined to bring hunters, shooters & sportsmen a wide selection of the best hunting optics money can buy, while at the same time creating revolutionary capabilities for the serious hunter. Present this coupon for $25 OFF your in-store purchase of $150 or more! Valid through December 31, 2016 Not valid online, on gift cards, non-merchandise items, licenses, previous purchases or special orders. Excludes NIKON, CARHARTT, UGG, THE NORTH FACE, PATAGONIA, MERRELL, DANSKO, AVET REELS, SHIMANO, G.LOOMIS & SAGE items. Cannot be combined with any other offer. No copies. One per customer. No cash value. CT2016 Kittery Trading Post / Rte 1 Kittery, ME / Mon-Sat 9-9, Sun 10-6 / 888-587-6246 / ktp.com / ktpguns.com 2016 CONNECTICUT HUNTING & TRAPPING Contents Licenses, Permits & Tags ............................................................ 8–10 Firearms Hunting Licenses Small Game and Deer Archery Deer and Turkey Permits Pheasant Tags Waterfowl Stamps Hunter Education Requirements Lost License Handicapped License Hunting Laws & Regulations ..................................................... 12–15 BE BEAR AWARE, page 6 Definitions Learn what you should do if you encounter bears in the outdoors or around Closed Seasons your home. -

Where-To-Go Fifth Edition Buckskin Lodge #412 Order of the Arrow, WWW Theodore Roosevelt Council Boy Scouts of America 2002

Where-to-Go Fifth Edition Buckskin Lodge #412 Order of the Arrow, WWW Theodore Roosevelt Council Boy Scouts of America 2002 0 The "Where to Go" is published by the Where-to-Go Committee of the Buckskin Lodge #412 Order of the Arrow, WWW, of the Theodore Roosevelt Council, #386, Boy Scouts of America. FIFTH EDITION September, 1991 Updated (2nd printing) September, 1993 Third printing December, 1998 Fourth printing July, 2002 Published under the 2001-2002 administration: Michael Gherlone, Lodge Chief John Gherlone, Lodge Adviser Marc Ryan, Lodge Staff Adviser Edward A. McLaughlin III, Scout Executive Where-to-Go Committee Adviser Stephen V. Sassi Chairman Thomas Liddy Original Word Processing Andrew Jennings Michael Nold Original Research Jeffrey Karz Stephen Sassi Text written by Stephen Sassi 1 This guide is dedicated to the Scouts and volunteers of the Theodore Roosevelt Council Boy Scouts of America And the people it is intended to serve. Two roads diverged in a wood, and I - I took the one less traveled by, And that made all the difference...... - R.Frost 2 To: All Scoutmasters From: Stephen V. Sassi Buckskin Lodge Where to Go Adviser Date: 27 June 2002 Re: Where to Go Updates Enclosed in this program packet are updates to the Order of Arrow Where to Go book. Only specific portions of the book were updated and the remainder is unchanged. The list of updated pages appears below. Simply remove the old pages from the book and discard them, replacing the old pages with the new pages provided. First two pages Table of Contents - pages 1,2 Chapter 3 - pages 12,14 Chapter 4 - pages 15-19,25,26 Chapter 5 - All except page 35 (pages 27-34,36) Chapter 6 - pages 37-39, 41,42 Chapter 8 - pages 44-47 Chapter 9 - pages 51,52,54 Chapter 10 - pages 58,59,60 Chapter 11 - pages 62,63 Appendix - pages 64,65,66 We hope that this book will provide you with many new places to hike and camp. -

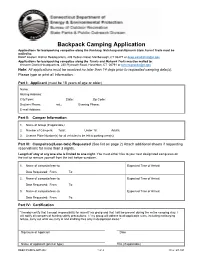

Backpacking Camping Application

Backpack Camping Application Applications for backpacking campsites along the Pachaug, Natchaug and Nipmuck State Forest Trails must be mailed to: DEEP Eastern District Headquarters, 209 Hebron Road, Marlborough, CT 06477 or [email protected] Applications for backpacking campsites along the Tunxis and Mohawk Trails must be mailed to: Western District Headquarters, 230 Plymouth Road, Harwinton, CT 06791 or [email protected] Note: All applications must be received no later than 14 days prior to requested camping date(s). Please type or print all information. Part I: Applicant (must be 18 years of age or older) Name: Mailing Address: City/Town: State: Zip Code: Daytime Phone: ext.: Evening Phone: E-mail Address: Part II: Camper Information 1. Name of Group (If applicable): 2. Number of Campers: Total: Under 18: Adults: 3. License Plate Number(s) for all vehicles to be left in parking area(s): Part III: Campsite(s)/Lean-to(s) Requested (See list on page 2) Attach additional sheets if requesting reservations for more than 3 nights. Length of stay at any one site is limited to one night. You must either hike to your next designated camp area on the trail or remove yourself from the trail before sundown. 1. Name of campsite/lean-to: Expected Time of Arrival: Date Requested: From: To: 2. Name of campsite/lean-to: Expected Time of Arrival: Date Requested: From: To: 3. Name of campsite/lean-to: Expected Time of Arrival: Date Requested: From: To: Part IV: Certification “I hereby certify that I accept responsibility for myself/ my group and that I will be present during the entire camping stay. -

The Connecticut Ornithological Association 314 Unquowaroad Non-Profit Org

Winter 1990 Contents Volume X Number 1 January 1990 THE 1 A Tribute to Michael Harwood David A Titus CONNECTICUT 2 Site Guide Birder's Guide to the Mohawk State Forest and Vicinity Arnold Devine and Dwight G. Smith I WARBLER ~ A Journal of Connecticut Ornithology 10 Non-Breeding Bald Eagles in Northwest Con necticut During Late Spring and Summer D. A Hopkins 15 Notes on Birds Using Man-Made Nesting Materials William E. Davis, Jr. 19 Connecticut Field Notes Summer: June 1 -July 31, 1989 Jay Kaplan 24 Corrections The Connecticut Ornithological Association 314 UnquowaRoad Non-Profit Org. Fairfield, cr 06430 U.S. Postage PAID Fairfield, CT Permit No. 275 :.'• ~}' -'~~- .~ ( Volume X No. 1 January 1990 Pages 1-24 j ~ THE CONNECTICUf ORNITHOLOGICAL A TRIBUTE TO MICHAEL HARWOOD ASSOCIATION Michael Harwood (1934-1989) "I remember a lovely May morning in Central Park in New York. ... PreBident Debra M. Miller, Franklin, MA A friend and I heard an unfamiliar song, a string of thin, wiry notes Vice-President climbing the upper register in small steps; we traced it to a tiny yellow Frank Mantlik, S. Norwalk •, bird in a just-planted willow tree. To say that the bird was 'yellow' Secretary does not do it justice. Its undersides were the very essence of yellow, Alison Olivieri, Fairfield and this yellow was set off by the black stripes on the breast, by the Trea.urer •• dramatic triangle of black drawn on its yellow face, and by the Carl J. Trichka, Fairfield chestnut piping on its back, where the yellow turned olive .. -

Block Reports

MATRIX SITE: 1 RANK: MY NAME: Kezar River SUBSECTION: 221Al Sebago-Ossipee Hills and Plains STATE/S: ME collected during potential matrix site meetings, Summer 1999 COMMENTS: Aquatic features: kezar river watershed and gorgeassumption is good quality Old growth: unknown General comments/rank: maybe-yes, maybe (because of lack of eo’s) Logging history: yes, 3rd growth Landscape assessment: white mountian national forest bordering on north. East looks Other comments: seasonal roads and homes, good. Ownership/ management: 900 state land, small private holdings Road density: low, dirt with trees creating canopy Boundary: Unique features: gorge, Cover class review: 94% natural cover Ecological features, floating keetle hole bog.northern hard wood EO's, Expected Communities: SIZE: Total acreage of the matrix site: 35,645 LANDCOVER SUMMARY: 94 % Core acreage of the matrix site: 27,552 Natural Cover: Percent Total acreage of the matrix site: 35,645 Open Water: 2 Core acreage of the matrix site: 27,552 Transitional Barren: 0 % Core acreage of the matrix site: 77 Deciduous Forest: 41 % Core acreage in natural cover: 96 Evergreen Forest: 18 % Core acreage in non- natural cover: 4 Mixed Forest: 31 Forested Wetland: 1 (Core acreage = > 200m from major road or airport and >100m from local Emergent Herbaceous Wetland: 2 roads, railroads and utility lines) Deciduous shrubland: 0 Bare rock sand: 0 TOTAL: 94 INTERNAL LAND BLOCKS OVER 5k: 37 %Non-Natural Cover: 6 % Average acreage of land blocks within the matrix site: 1,024 Percent Maximum acreage of any -

Documenting and Protecting New England's Old-Growth Forests

Documenting and Protecting New England’s Old-Growth Forests Written By: Jack Ruddat Documenting and Protecting New England’s Old-Growth Forests An Interactive Qualifying Project submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science by Jack Ruddat Date: May 13, 2020 Report Submitted to: Dr. Uma Kumar and Dr. Ingrid Shockey Worcester Polytechnic Institute This report represents work of WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its web site without editorial or peer review. For more information about the projects program at WPI, see http://www.wpi.edu/Academics/Projects Abstract Old-growth forests in New England have become exceedingly rare over the centuries but contribute greatly to biodiversity, ecological stability, and scientific knowledge. Many of these remaining forests are either unrecognized or lack protection from development. The goal of this project was to promote the preservation and appreciation for old-growth forests in New England. The state of Connecticut was chosen for mapping and documenting remaining standing old- growth forests, understanding stakeholders’ positions and preservation practices, and identifying suitability for public visitation. i Executive Summary Executive Summary Old-growth forests in the United States can be identified as areas of land that have been continuously forested since before the early to mid-1800’s (Jönsson, Fraver, & Jonsson, 2009; Kershner & Leverett, 2004). They have become exceedingly rare over the centuries but contribute greatly to biodiversity and ecological stability (MacKinnon, 1998). Furthermore, they are laboratories for scientific knowledge regarding forest succession and development, plant relationships, and nutrient cycling (David et al., 1996). -

Meeting Notes for Thursday, December 20, 2019

P.O. Box 57 Durham, CT 06422-0057 13th Meeting Notes for Thursday, December 20, 2019 Call to Order: The meeting was held at CFPA Library -16 Meriden Rd., Rockfall The meeting called to order at 6:45 by Ron Hocutt Attendance: Ron Hocutt, Ruth Beardsey, Ruth Strontzer, Meg Sautter, Diane Ciano, Eric Hammerling Guests: Danielle Borelli, Vevette Greenberg, Gary Rutkauskas Excused: Laurie Giannotti Absent: 0 Review Meeting Minutes: The meeting minutes of September 19, 2019 were reviewed. Motion to accept by after corrections by Meg Sautter 2nd Ruth Strontzer State Park & Forest Updates: Natchaug State Forest: Natchaug is still closed due to logging and clean up operations. Naugatuck State Forest: Vevette & Meg walked trails and noted the large tree reported in September was cleared. Trails were in good condition. Sunrise & Machimoodus State Park: Ruth Strontzer reported that she has met with DEEP Supervisor or Jack Hines. He is in favor of looking to expand trails on the Sunrise side, the proposal for a permanent horse camp and working on establishing “Ginger’s Garden.” Meg Sautter reported that there was a large tree down on the Sunrise side on the yellow trail. They removed some branches, but were not successful in clearing it. Sunrise & Machimoodus State Park con’t: Ruth reported that there was a very successful program with Stephen Gencarella, Professor of Folklore Studies at the University of MA, who walked the trails and told stories of the area. About 80 people attended. State Park & Forest Updates continued: Pachaug State Forest: No report Bissell Trail: No report. Meg will contact [email protected] 860-242-1158 860- 797-7059 mobile Ruth Strontzer reported on several state parks and trails: Chatfield Hollow State Park: Trails are in good shape. -

A.T. History & Cooperative Management

Appalachian Trail Cooperative Management History After several decades of Appalachian Trail (A.T.) design and construction by A.T. clubs and the Appalachian Trail Conservancy (ATC) the A.T. became one of the first of two national scenic trails designated under the 1968 National Trails System Act. The purpose of that Act was to provide the means to develop a national trails system for “the ever-increasing outdoor recreation needs of an expanding population and in order to promote the preservation of, public access to, travel within, and enjoyment and appreciation of the open-air, outdoor areas and historic resources of the Nation.” The Act promoted the development of trails “primarily, near the urban areas of the Nation, and secondarily, within scenic areas and along historic travel routes of the Nation which are often more remotely located.” The Act formally recognized the Department of the Interior, in consultation with the Department of Agriculture, as the administrator for the Appalachian National Scenic Trail. It also recognized the important role of volunteers and nonprofit organizations to support the federal agencies: “The Congress recognizes the valuable contributions that volunteers and private, nonprofit trail groups have made to the development and maintenance of the Nation's trails. In recognition of these contributions, it is further the purpose of this Act to encourage and assist volunteer citizen involvement in the planning, development, maintenance, and management, where appropriate, of trails.” The most significant outcome of the 1968 Act, and its 1978 amendments, was to provide a federal framework to acquire lands and permanently protect a Trail corridor.