Documenting and Protecting New England's Old-Growth Forests

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Register of Historic Places Received JUL 2 5 Isee Inventory

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use omy National Register of Historic Places received JUL 2 5 isee Inventory Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections____________________________________ 1. Name___________________________ historic________N/A____*____________________________________________________ Connecticut State Park and Forest Depression-Era Federal Work Relief and or common Programs Structures Thematic Resource_______________________ 2. Location____________________________ street & number See inventory Forms___________________________-M/Anot for publication city, town______See Inventory Forms _ vicinity of__________________________ state_______Connecticut code 09_____county See Inventory Forms___code " 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district _ X_ public _ X- occupied agriculture museum _ X- building(s) private unoccupied commercial _ X-park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process _ X- Ves: restricted government scientific X thematic being considered - yes: unrestricted industrial transportation group IN/A no military other: 4. Owner of Property Commissionier Stanley Pac name Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection street & number 165 Capitol Avenue city, town___Hartford______________ vicinity of___________state Connecticut -

Integrated Pest Management (Ipm) for Connecticut

Plant Science Day The Annual Samuel W. Johnson Lecture • Short Talks • Demonstrations • Field Experiments • Passport for Kids Pesticide Credits • Century Farm Award • Barn Exhibits Lockwood Farm, Hamden Wednesday, August 3, 2005 XYXYXYXYXYXY History of Lockwood Farm, Hamden Lockwood Farm is a research farm of the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station. Historically, the farm was purchased in 1910 with monies provided by the Lockwood Trust Fund, a private endowment. The original farm was 19.6 acres with a barn and a house. Since then, several adjacent tracts of land were purchased, enlarging the acres to 75.0. The farm is located in the extreme southern portion of the Central Lowland Physiographic Province. This lowland region is underlain by red stratified sandstone and shale of Triassic age from which resistant lava flows project as sharp ridges. One prominent ridge, observed from the farm, is Sleeping Giant Mountain that lies to the north. The mountain is composed of basalt, a dense igneous rock commonly used as a building material and ballast for railroad tracks. The topography of the farm is gently rolling to hilly and was sculpted by the Wisconsin glacier that overrode the area some 10,000 years ago and came to rest in the vicinity of Long Island. A prominent feature of the farm is a large basaltic boulder that was plucked from Sleeping Giant by the advancing glacier and came to rest on the crest of a hillock to the south of the upper barns. From this hillock, Sleeping Giant State Park comes into full view and is a favorite spot for photographers and artists. -

2016 Connecticut Hunting & Trapping Guide

2016 CONNECTICUT HUNTING & TRAPPING Connecticut Department of VISIT OUR WEBSITE Energy & Environmental Protection www.ct.gov/deep/hunting MONARCH® BINOCULARS Built to satisfy the incredible needs of today’s serious outdoorsmen & women, MONARCH binoculars not only bestow the latest in optical innovation upon the passions of its owner, but offer dynamic handling & rugged performance for virtually any hunting situation. MONARCH® RIFLESCOPES Bright, clear, precise, rugged - just a few of the attributes knowledgeable hunters commonly use to describe Nikon® riflescopes. Nikon® is determined to bring hunters, shooters & sportsmen a wide selection of the best hunting optics money can buy, while at the same time creating revolutionary capabilities for the serious hunter. Present this coupon for $25 OFF your in-store purchase of $150 or more! Valid through December 31, 2016 Not valid online, on gift cards, non-merchandise items, licenses, previous purchases or special orders. Excludes NIKON, CARHARTT, UGG, THE NORTH FACE, PATAGONIA, MERRELL, DANSKO, AVET REELS, SHIMANO, G.LOOMIS & SAGE items. Cannot be combined with any other offer. No copies. One per customer. No cash value. CT2016 Kittery Trading Post / Rte 1 Kittery, ME / Mon-Sat 9-9, Sun 10-6 / 888-587-6246 / ktp.com / ktpguns.com 2016 CONNECTICUT HUNTING & TRAPPING Contents Licenses, Permits & Tags ............................................................ 8–10 Firearms Hunting Licenses Small Game and Deer Archery Deer and Turkey Permits Pheasant Tags Waterfowl Stamps Hunter Education Requirements Lost License Handicapped License Hunting Laws & Regulations ..................................................... 12–15 BE BEAR AWARE, page 6 Definitions Learn what you should do if you encounter bears in the outdoors or around Closed Seasons your home. -

2020 CT Fishing Guide

Share the Experience—Take Someone Fishing • APRIL 11 Opening Day Trout Fishing 2020 CONNECTICUT FISHING GUIDE INLAND & MARINE YOUR SOURCE »New Marine For CT Fishing Regulations for 2020 Information See page 54 Connecticut Department of Energy & Environmental Protection www.ct.gov/deep/fishing FISHING REGULATIONS GUIDE - VA TRIM: . 8˝ X 10-1/2˝ (AND VARIOUS OTHER STATES) BLEED: . 8-1/4˝ X 10-3/4˝ SAFETY: . 7˝ X 10˝ TRIM TRIM SAFETY TRIM BLEED BLEED SAFETY BLEED BLEED TRIM TRIM SAFETY SAFETY There’s a reason they say, Curse like a sailor. That’s why we offer basic plans starting at $100 a year with options that won’t depreciate your watercraft and accessories*. Progressive Casualty Ins. Co. & affi liates. Annual premium for a basic liability policy not available all states. Prices vary based on how you buy. *Available with comprehensive and collision coverage. and collision with comprehensive *Available buy. you on how based vary Prices all states. available not policy liability a basic for Annual premium liates. & affi Co. Ins. Casualty Progressive 1.800.PROGRESSIVE | PROGRESSIVE.COM SAFETY SAFETY TRIM TRIM BLEED BLEED TRIM TRIM TRIM BLEED BLEED SAFETY SAFETY Client: Progressive Job No: 18D30258.KL Created by: Dalon Wolford Applications: InDesign CC, Adobe Photoshop CC, Adobe Illustrator CC Job Description: Full Page, 4 Color Ad Document Name: Keep Left ad / Fishing Regulations Guide - VA and various other states Final Trim Size: 7-7/8˝ X 10-1/2˝ Final Bleed: 8-1/8˝ X 10-13/16˝ Safety: 7˝ X 10˝ Date Created: 10/26/18 2020 CONNECTICUT FISHING GUIDE INLAND REGULATIONS INLAND & MARINE Easy two-step process: 1. -

Keeping Paradise Unpaved in the Trenches of Land Preservation

CONNECTICUT Woodlands CFPA’S LEGISLATIVE for INSIDE AGENDA 2014 KEEPING PARADISE UNPAVED IN THE TRENCHES OF LAND PRESERVATION The Magazine of the Connecticut Forest & Park Association Spring 2014 Volume 79 No. 1 The ConnectiCuT ForesT & Park assoCiaTion, inC. OFFICERS PRESIDENT, ERIC LUKINGBEAL, Granby VICE-PRESIDENT, WILLIAM D. BRECK, Killingworth VICE-PRESIDENT, GEOFFREY MEISSNER, Plantsville VICE-PRESIDENT, DAVID PLATT, Higganum VICE-PRESIDENT, STARR SAYRES, East Haddam TREASURER, JAMES W. DOMBRAUSKAS, New Hartford SECRETARY, ERIC HAMMERLING, West Hartford FORESTER, THOMAS J. DEGNAN, JR., East Haddam DIRECTORS RUSSELL BRENNEMAN, Westport ROBERT BUTTERWORTH, Deep River STARLING W. CHILDS, Norfolk RUTH CUTLER, Ashford THOMAS J. DEGNAN, JR., East Haddam CAROLINE DRISCOLL, New London ASTRID T. HANZALEK, Suffield DAVID LAURETTI, Bloomfield JEFFREY BRADLEY MICHAEL LECOURS, Farmington This pond lies in a state park few know about. See page 10. DAVID K. LEFF, Collinsville MIRANDA LINSKY, Middletown SCOTT LIVINGSTON, Bolton JEFF LOUREIRO, Canton LAUREN L. McGREGOR, Hamden JEFFREY O’DONNELL, Bristol Connecting People to the Land Annual Membership RICHARD WHITEHOUSE, Glastonbury Our mission: The Connecticut Forest & Park Individual $ 35 HONORARY DIRECTORS Association protects forests, parks, walking Family $ 50 GORDON L. ANDERSON, St. Johns, FL trails and open spaces for future generations by HARROL W. BAKER, JR., Bolton connecting people to the land. CFPA directly Supporting $ 100 RICHARD A. BAUERFELD, Redding involves individuals and families, educators, GEORGE M. CAMP, Middletown Benefactor $ 250 ANN M. CUDDY, Ashland, OR community leaders and volunteers to enhance PRUDENCE P. CUTLER, Farmington and defend Connecticut’s rich natural heritage. SAMUEL G. DODD, North Andover, MA CFPA is a private, non-profit organization that Life Membership $ 2500 JOHN E. -

YOUR SOURCE for CT Fishing Information

Share the Experience—Take Someone Fishing • APRIL 14 Opening Day Trout Fishing 2018 CONNECTICUT ANGLER’S GUIDE INLAND & MARINE FISHING YOUR SOURCE For CT Fishing Information »New Trout & »New Inland »New Marine Salmon Stamp Regulations Regulations See page 8 & 20 for 2018 for 2018 See page 20 See page 58 Connecticut Department of Energy & Environmental Protection www.ct.gov/deep/fishing FISHING REGULATIONS GUIDE - GA TRIM: . 8˝ X 10-1/2˝ (AND VARIOUS OTHER STATES) BLEED: . 8-1/4˝ X 10-3/4˝ SAFETY: . 7˝ X 10˝ TRIM TRIM SAFETY TRIM BLEED BLEED SAFETY BLEED BLEED TRIM TRIM SAFETY SAFETY SAFETY SAFETY TRIM TRIM BLEED BLEED TRIM TRIM TRIM BLEED BLEED SAFETY SAFETY Client: Progressive Job No: 16D00890 Created by: Dalon Wolford Applications: InDesign CC, Adobe Photoshop CC, Adobe Illustrator CC Job Description: Full Page, 4 Color Ad Document Name: Bass ad / Fishing Regulations Guide - GA and various other states Final Trim Size: 7-7/8˝ X 10-1/2˝ Final Bleed: 8-1/8˝ X 10-13/16˝ Safety: 7˝ X 10˝ Date Created: 11/7/16 FISHING REGULATIONS GUIDE - GA TRIM: . 8˝ X 10-1/2˝ (AND VARIOUS OTHER STATES) BLEED: . 8-1/4˝ X 10-3/4˝ SAFETY: . 7˝ X 10˝ TRIM TRIM SAFETY TRIM BLEED BLEED SAFETY BLEED BLEED TRIM TRIM SAFETY SAFETY 2018 CONNECTICUT ANGLER’S GUIDE INLAND REGULATIONS INLAND & MARINE FISHING Easy two-step process: 1. Check the REGULATION TABLE (page 21) for general statewide Contents regulations. General Fishing Information 2. Look up the waterbody in the LAKE AND PONDS Directory of Services Phone Numbers .............................2 (pages 32–41) or RIVERS AND STREAMS (pages 44–52) Licenses ......................................................................... -

Where-To-Go Fifth Edition Buckskin Lodge #412 Order of the Arrow, WWW Theodore Roosevelt Council Boy Scouts of America 2002

Where-to-Go Fifth Edition Buckskin Lodge #412 Order of the Arrow, WWW Theodore Roosevelt Council Boy Scouts of America 2002 0 The "Where to Go" is published by the Where-to-Go Committee of the Buckskin Lodge #412 Order of the Arrow, WWW, of the Theodore Roosevelt Council, #386, Boy Scouts of America. FIFTH EDITION September, 1991 Updated (2nd printing) September, 1993 Third printing December, 1998 Fourth printing July, 2002 Published under the 2001-2002 administration: Michael Gherlone, Lodge Chief John Gherlone, Lodge Adviser Marc Ryan, Lodge Staff Adviser Edward A. McLaughlin III, Scout Executive Where-to-Go Committee Adviser Stephen V. Sassi Chairman Thomas Liddy Original Word Processing Andrew Jennings Michael Nold Original Research Jeffrey Karz Stephen Sassi Text written by Stephen Sassi 1 This guide is dedicated to the Scouts and volunteers of the Theodore Roosevelt Council Boy Scouts of America And the people it is intended to serve. Two roads diverged in a wood, and I - I took the one less traveled by, And that made all the difference...... - R.Frost 2 To: All Scoutmasters From: Stephen V. Sassi Buckskin Lodge Where to Go Adviser Date: 27 June 2002 Re: Where to Go Updates Enclosed in this program packet are updates to the Order of Arrow Where to Go book. Only specific portions of the book were updated and the remainder is unchanged. The list of updated pages appears below. Simply remove the old pages from the book and discard them, replacing the old pages with the new pages provided. First two pages Table of Contents - pages 1,2 Chapter 3 - pages 12,14 Chapter 4 - pages 15-19,25,26 Chapter 5 - All except page 35 (pages 27-34,36) Chapter 6 - pages 37-39, 41,42 Chapter 8 - pages 44-47 Chapter 9 - pages 51,52,54 Chapter 10 - pages 58,59,60 Chapter 11 - pages 62,63 Appendix - pages 64,65,66 We hope that this book will provide you with many new places to hike and camp. -

The Highland Lake Watershed Association Welcomes You to Highland Lake

The Highland Lake Watershed Association Welcomes You to Highland Lake Highland Lake Watershed (HLWA) The Highland Lake Watershed Association (HLWA) is pleased to welcome you to the neighborhood. HLWA is a nonprofit 501(c)(3) organization which began in 1959 dedicated to the preservation and protection of Highland Lake and its watershed. Dedicated volunteers make up the HLWA board and committees. Benefits of HWLA Membership Help make a difference and improve the quality of life around the lake. Meet your neighbors and make new friends. Participate in special events where you can socialize and exchange ideas while raising funds to promote the focus and mission of HLWA. Learn what keeps a lake and watershed clean, healthy and conducive to many more years of beauty and enjoyment. Membership in HLWA is voluntary and we hope you will join HLWA and become involved. Visit our website at www.hlwa.org for more information. If you have any questions or comments, we would love to hear from you! The HLWA Board of Directors Email: [email protected] Mailing: PO Box 1022, Winsted CT 06098-1022 Follow us on #hlwainsta What Does HLWA Do? *Works with local authorities to maintain water quality and safety which benefits all residents *Conducts monthly water sampling and testing April through November *Raises money to protect and preserve water quality and the natural resources of the watershed *Manages our Legacy Program which acquires land in the watershed to preserve open space and reduce water runoff *Sponsors events like “Evening on Highland Lake,” Boat -

Johnsons Announce Gift of 71-Acre Conservation Easement At

G RANBY EWSLETTER Land Trust N Preserving Granby’s Natural Heritage www.granbylandtrust.org C PO Box 23 C Granby, Connecticut 06035 C Volume 5 Johnsons Announce Gift of 71-Acre Conservation Easement at Annual Meeting he unusually warm and sunny late October Tday suggested that this would be a special Land Trust Annual Meeting. It was in many ways. With fall’s full colors on parade, almost 100 land trust members gathered on October 21st and were treated to a walk through one of Granby’s most beautiful properties – Paula and Whitey Johnson’s 90-acre parcel on Simsbury Road in West Granby – followed by an old-fashioned outdoor picnic at the Johnson’s house. It was a family affair all day. On the walk The Land Trust led by Whitey Johnson, kids ran Whitey Johnson talks about his property and its history thanks Paula ahead of the adults during the Annual Meeting Hike in October. and Whitey through the rolling fields, by the solid old stonewalls and into the Johnson for their Johnson’s woods which are bounded by the Land Trust Receives Three commitment and McLean Game Refuge. After the walk, every- Conservation Easements in 2007 one gathered together and the annual meeting • The Johnson Family - 71 acres dedication to was called to order. During the meeting, the • The Werner Family - 40 acres (see pg. 14) Granby and the Johnsons announced that they intended to • The Brown Family - 10+ acres (see pg. 7) give the Land Trust a conservation easement legacy they have over 71-acres of this spectacular land, forever built for future preserving it as open space. -

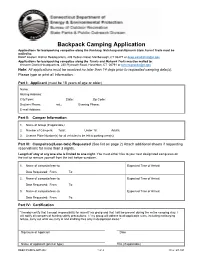

Backpacking Camping Application

Backpack Camping Application Applications for backpacking campsites along the Pachaug, Natchaug and Nipmuck State Forest Trails must be mailed to: DEEP Eastern District Headquarters, 209 Hebron Road, Marlborough, CT 06477 or [email protected] Applications for backpacking campsites along the Tunxis and Mohawk Trails must be mailed to: Western District Headquarters, 230 Plymouth Road, Harwinton, CT 06791 or [email protected] Note: All applications must be received no later than 14 days prior to requested camping date(s). Please type or print all information. Part I: Applicant (must be 18 years of age or older) Name: Mailing Address: City/Town: State: Zip Code: Daytime Phone: ext.: Evening Phone: E-mail Address: Part II: Camper Information 1. Name of Group (If applicable): 2. Number of Campers: Total: Under 18: Adults: 3. License Plate Number(s) for all vehicles to be left in parking area(s): Part III: Campsite(s)/Lean-to(s) Requested (See list on page 2) Attach additional sheets if requesting reservations for more than 3 nights. Length of stay at any one site is limited to one night. You must either hike to your next designated camp area on the trail or remove yourself from the trail before sundown. 1. Name of campsite/lean-to: Expected Time of Arrival: Date Requested: From: To: 2. Name of campsite/lean-to: Expected Time of Arrival: Date Requested: From: To: 3. Name of campsite/lean-to: Expected Time of Arrival: Date Requested: From: To: Part IV: Certification “I hereby certify that I accept responsibility for myself/ my group and that I will be present during the entire camping stay. -

The Connecticut Ornithological Association 314 Unquowaroad Non-Profit Org

Winter 1990 Contents Volume X Number 1 January 1990 THE 1 A Tribute to Michael Harwood David A Titus CONNECTICUT 2 Site Guide Birder's Guide to the Mohawk State Forest and Vicinity Arnold Devine and Dwight G. Smith I WARBLER ~ A Journal of Connecticut Ornithology 10 Non-Breeding Bald Eagles in Northwest Con necticut During Late Spring and Summer D. A Hopkins 15 Notes on Birds Using Man-Made Nesting Materials William E. Davis, Jr. 19 Connecticut Field Notes Summer: June 1 -July 31, 1989 Jay Kaplan 24 Corrections The Connecticut Ornithological Association 314 UnquowaRoad Non-Profit Org. Fairfield, cr 06430 U.S. Postage PAID Fairfield, CT Permit No. 275 :.'• ~}' -'~~- .~ ( Volume X No. 1 January 1990 Pages 1-24 j ~ THE CONNECTICUf ORNITHOLOGICAL A TRIBUTE TO MICHAEL HARWOOD ASSOCIATION Michael Harwood (1934-1989) "I remember a lovely May morning in Central Park in New York. ... PreBident Debra M. Miller, Franklin, MA A friend and I heard an unfamiliar song, a string of thin, wiry notes Vice-President climbing the upper register in small steps; we traced it to a tiny yellow Frank Mantlik, S. Norwalk •, bird in a just-planted willow tree. To say that the bird was 'yellow' Secretary does not do it justice. Its undersides were the very essence of yellow, Alison Olivieri, Fairfield and this yellow was set off by the black stripes on the breast, by the Trea.urer •• dramatic triangle of black drawn on its yellow face, and by the Carl J. Trichka, Fairfield chestnut piping on its back, where the yellow turned olive .. -

Block Reports

MATRIX SITE: 1 RANK: MY NAME: Kezar River SUBSECTION: 221Al Sebago-Ossipee Hills and Plains STATE/S: ME collected during potential matrix site meetings, Summer 1999 COMMENTS: Aquatic features: kezar river watershed and gorgeassumption is good quality Old growth: unknown General comments/rank: maybe-yes, maybe (because of lack of eo’s) Logging history: yes, 3rd growth Landscape assessment: white mountian national forest bordering on north. East looks Other comments: seasonal roads and homes, good. Ownership/ management: 900 state land, small private holdings Road density: low, dirt with trees creating canopy Boundary: Unique features: gorge, Cover class review: 94% natural cover Ecological features, floating keetle hole bog.northern hard wood EO's, Expected Communities: SIZE: Total acreage of the matrix site: 35,645 LANDCOVER SUMMARY: 94 % Core acreage of the matrix site: 27,552 Natural Cover: Percent Total acreage of the matrix site: 35,645 Open Water: 2 Core acreage of the matrix site: 27,552 Transitional Barren: 0 % Core acreage of the matrix site: 77 Deciduous Forest: 41 % Core acreage in natural cover: 96 Evergreen Forest: 18 % Core acreage in non- natural cover: 4 Mixed Forest: 31 Forested Wetland: 1 (Core acreage = > 200m from major road or airport and >100m from local Emergent Herbaceous Wetland: 2 roads, railroads and utility lines) Deciduous shrubland: 0 Bare rock sand: 0 TOTAL: 94 INTERNAL LAND BLOCKS OVER 5k: 37 %Non-Natural Cover: 6 % Average acreage of land blocks within the matrix site: 1,024 Percent Maximum acreage of any