"Insurance" Under Florida's Chapter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lloyd's Minimum Standards

LLOYD’S MINIMUM STANDARDS MS1.1 – UNDERWRITING STRATEGY & PLANNING October 2017 1 MS1.1 – UNDERWRITING STRATEGY & PLANNING UNDERWRITING MANAGEMENT PRINCIPLES, MINIMUM STANDARDS AND REQUIREMENTS These are statements of business conduct required by Lloyd’s. The Principles and Minimum Standards are established under relevant Lloyd’s Byelaws relating to business conduct. All managing agents are required to meet the Principles and Minimum Standards. The Requirements represent the minimum level of performance required of any organisation within the Lloyd’s market to meet the Minimum Standards. Within this document the standards and supporting requirements (the “must dos” to meet the standard) are set out in the blue box at the beginning of each section. The remainder of each section consists of guidance which explains the standards and requirements in more detail and gives examples of approaches that managing agents may adopt to meet them. UNDERWRITING MANAGEMENT GUIDANCE This guidance provides a more detailed explanation of the general level of performance expected. They are a starting point against which each managing agent can compare its current practices to assist in understanding relative levels of performance. This guidance is intended to provide reassurance to managing agents as to approaches which would certainly meet the Principles and Minimum Standards and comply with the Requirements. However, it is appreciated that there are other options which could deliver performance at or above the minimum level and it is fully acceptable for managing agents to adopt alternative procedures as long as they can demonstrate the Requirements to meet the Principles and Minimum Standards. DEFINITIONS AFR: actuarial function report Benchmark Premium: The price for each risk at which the managing agent is expected to deliver their required results, in line with the approved Syndicate Business Plan. -

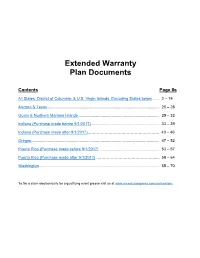

Extended Warranty Coverage

Extended Warranty Plan Documents Contents Page #s All States, District of Columbia, & U.S. Virgin Islands, Excluding States below ...... 2 – 19 Arizona & Texas ..................................................................................................... 20 – 28 Guam & Northern Mariana Islands ......................................................................... 29 – 32 Indiana (Purchase made before 9/1/2017) ............................................................. 33 – 39 Indiana (Purchase made after 9/1/2017)………………………………………………. 40 – 46 Oregon.................................................................................................................... 47 – 52 Puerto Rico (Purchase made before 9/1/2017) ...................................................... 53 – 57 Puerto Rico (Purchase made after 9/1/2017) ……………………………………….... 58 – 64 Washington ............................................................................................................. 65 – 70 To file a claim electronically for a qualifying event please visit us at www.americanexpress.com/onlineclaim. All States, District of Columbia, & U.S. Virgin Islands, Except States below Back to top EXTENDED WARRANTY DESCRIPTION OF COVERAGE Underwritten by AMEX Assurance Company Administrative Office, 20022 N. 31st Ave. MC: 08-01-20 Phoenix AZ 85027 For purchases charged to Your Account, Extended Warranty will extend the terms of the original manufacturer's warranty on warranties of five (5) years or less that are eligible in the United States of America, -

An Experimental Investigation of Extended Warranties

Volume 64 Issue 2 Article 4 7-1-2019 Protecting Consumers Through Mandatory Disclosures: An Experimental Investigation of Extended Warranties Breagin K. Riley Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/vlr Part of the Consumer Protection Law Commons Recommended Citation Breagin K. Riley, Protecting Consumers Through Mandatory Disclosures: An Experimental Investigation of Extended Warranties, 64 Vill. L. Rev. 285 (2019). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/vlr/vol64/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Villanova Law Review by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Riley: Protecting Consumers Through Mandatory Disclosures: An Experiment 2019] PROTECTING CONSUMERS THROUGH MANDATORY DISCLOSURES: AN EXPERIMENTAL INVESTIGATION OF EXTENDED WARRANTIES BREAGIN K. RILEY* AND AHMED E. TAHA** IMAGINE that you go to a consumer electronics store and buy a large- Iscreen television for $1,499. At the checkout counter, the cashier asks if you also wish to purchase an extended warranty for $249, which will pro- vide you three additional years of coverage beyond the manufacturer’s one-year warranty. Would you buy the extended warranty? What would drive your decision? If you are like most consumers, you would make this decision with little idea of the probability that the television will break down during the extended warranty’s coverage period and the cost of repairing it. But how would your decision and motivations change if the cashier told you there is only a 3% chance of the television needing repair during the first four years you own it and that the average cost of repairing the television is $300? These questions are the focus of this Article. -

Disclosure 1

ANNUAL REPORT 2012 Social Responsibility Vision MAPFRE wants to be the most trusted global insurance company Mission We are a multinational team that continuously strives to improve our service and develop the best relationship possible with our customers, distributors, suppliers, shareholders and Society Values SOLVENCY INTEGRITY SERVICE VOCATION INNOVATIVE LEADERSHIP COMMITTED TEAM Values SOLVENCY Financial strength with sustainable results. International diversification and consolidation in various markets. INTEGRITY Ethics govern the behaviour of all personnel. Socially responsible focus in all of our activities. SERVICE VOCATION Constant search for excellence in the development of our activities. Continuous initiatives focused on minding our relationship with our customers. INNOVATIVE LEADERSHIP Willingness to surpass ourselves and to constantly improve. Useful technology for servicing the businesses and their objectives. COMMITTED TEAM Total team commitment with MAPFRE’s project. Constant training and development of the team’s capabilities and skills. ANNUAL REPORT 2012 Social Responsibility Table of contents 2 1. Chairman’s Letter 4 4. MAPFRE’s social dimension 26 2. General Information 6 MAPFRE and its employees 27 MAPFRE and its customers 38 Presence 8 MAPFRE and its shareholders 55 MAPFRE Group’s corporate organization chart 9 MAPFRE and the professionals and entities Key economic figures 10 that help distribute products 57 Governing Bodies 11 MAPFRE and its suppliers 62 3. MAPFRE and Corporate Social 5. MAPFRE’s environmental -

YOUR GUIDE to CARD BENEFITS Your Guide to Benefits Describes the Benefits in Effect As of 4/1/14

M-119301 YOUR GUIDE TO CARD BENEFITS Your Guide to Benefits describes the benefits in effect as of 4/1/14. Benefit information in this guide replaces any prior benefit information you may have received. Please read and retain for your records. Your eligibility is determined by your financial institution. For more information about the benefits described in this guide, call the Benefit Administrator Visa at 1-800-397-9010, or call collect outside the U.S. at Signature Card 303-967-1093. For questions about your account, balance, or rewards points please call the customer service number on your Visa Signature card statement. Warranty Manager Service What is this benefit? Warranty Manager Service provides you with valuable features to help manage, use and even extend the warranties of eligible items purchased with your Visa Signature card. You can access these features with a simple toll-free call. Services include Warranty Registration and Extended Warranty Protection. Who is eligible for this benefit? You are eligible if you are a valid cardholder of an eligible Visa Signature card issued in the United States. Why should I use Warranty Registration to register my purchases? You’ll have peace of mind knowing that your purchases’ warranty information is registered and on file. Although Warranty Registration is not required for Extended Warranty Protection benefits, you are encouraged to take advantage of this valuable service. When arranging for a repair or replacement, instead of searching for critical documents, you can just pick up the phone and call the Benefit Administrator. How do I register my purchases? To register an eligible purchase call 1-800-397-9010, or call collect outside the U.S. -

Service Contracts & Extended Warranties

Service Contracts & Extended Warranties Greg Mitchell, Insurance Industry Group Chair, Frost Brown Todd Dan Tafel, VP of Business Development, Hornbeam Insurance Company December 17, 2020 frostbrowntodd.com Kentucky as a Service Contract Hub “The city of Louisville, Kentucky, home of both General Electric's Appliance Park and United Parcel Service’s Worldport, has become a major hub for the warranty industry. AIG Warranty Solutions is just across the Ohio River in Jeffersonville, Indiana, Best Buy's Geek Squad City is just south of the airport, and several new start-ups are downtown.” Warranty Week, November 14, 2019 frostbrowntodd.com What is a Service Contract? Service contracts are a kind of “quazi-insurance.” The service contract Provider, or obligor, assumes the risk of indemnifying the contract holder for the cost of repairing or replacing property covered by the service contract. Service Contracts may only cover loss due to a defect in materials or workmanship, or normal wear and tear. Service Contracts cannot cover loss from theft or loss. Service contracts are carved out of the insurance code in most states and regulated separately. frostbrowntodd.com Product Spectrum • Extended Warranty / Service • Insurance Contract • Manufacturer Warranty I want my product replaced or repaired if it is I want my product I want my product replaced stolen or replaced if it fails to or repaired if it wears out anything function as designed happens to it and promised frostbrowntodd.com Types of Service Contracts Consumer Motor Commercial Home Vehicle Home and Motor Vehicle Contracts are Uncertainty exists with regards to the often regulated differently than other application of service contract consumer service contracts regulations in the commercial context. -

Health Alliance Medicare Guide HMO Rx 2 (HMO) / Health Alliance Medicare Guide HMO Rx (HMO)

Health Alliance Medicare Guide HMO Rx 2 (HMO) / Health Alliance Medicare Guide HMO Rx (HMO) 2021 Summary of Benefits January 1, 2021 – December 31, 2021 Call toll-free 1-877-933-8454 daily from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. local time. Voicemail is used on holidays and weekends from April 1 to September 30. TTY 711 healthalliancemedicare.org Y0034_21_89520_M 1 This booklet gives you a summary of what our plans cover and what you pay. It doesn't list every service we cover or every limitation or exclusion. For a complete list of covered services, call us and ask for the Evidence of Coverage. Options for Getting Medicare Benefits • Original Medicare (fee-for-service), which is run by the federal government • Medicare Advantage through a private company, like Health Alliance Medicare Tips for Comparing Medicare Options This booklet allows you to compare costs and benefits for our plans. • If you want to compare our plans with other Medicare Advantage plans, ask other plans for their Summary of Benefits booklets or use the Medicare Plan Finder at medicare.gov. • If you want to know more about the coverage and costs of Original Medicare, look in your Medicare and You handbook. You can find it at medicare.gov. You can also get a copy by calling 1-800-MEDICARE (1-800-633-4227), 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. TTY users should call 1-877-486-2048. Booklet Sections • Things to Know • Monthly Premium, Deductible and Limits on How Much You Pay for Covered Services • Covered Medical and Hospital Benefits • Prescription Drug Benefits • Additional Covered Benefits • About Us This document is available in other formats, such as Braille and large print. -

AMTLC-AMZ-SMG (11-15) 1 SMARTGUARD PROTECTION PLAN TERMS and CONDITIONS CANADA Extended Warranty Contract Administrator: AMT

SMARTGUARD PROTECTION PLAN TERMS AND CONDITIONS CANADA Extended Warranty Contract Administrator: AMT Warranty Corp. of Canada, ULC | 421 7th Avenue S.W., Suite 1700 | Calgary, Alberta T2P 4K9 | Toll-Free: 1-844-347-4441 www.MySmartGuard.com CONGRATULATIONS! Thank You for Your recent purchase of the SmartGuard Protection Plan (the “Extended Warranty Contract”, “Contract”). We hope You enjoy the added comfort and protection this Extended Warranty Contract provides. Please keep this Extended Warranty Contract document and Your Contract Purchase Receipt as You will need them to verify Your coverage at time of Claim. This information will serve as a valuable reference guide and will help You determine what is covered by this Extended Warranty Contract. From the day You purchase this Extended Warranty Contract the Administrator will assist You in understanding Your Extended Warranty Contract benefits. DEFINITIONS Throughout this Extended Warranty Contract, the following capitalized words have the stated meaning – 1. “We”, “Us”, “Our”: the party or parties obligated to provide service under this 11. “Deductible”: the amount You are required to pay, per Claim, for services covered Extended Warranty Contract as shown in the “SPECIAL JURISDICTIONAL under this Extended Warranty Contract (if any). REQUIREMENTS” section and applicable to Your province/territory. 12. “Term”: the period of time in which the provisions of this Extended Warranty 2. “Administrator”: the entity responsible for administrating benefits to You in Contract are valid. accordance with the Extended Warranty Contract terms and conditions, AMT 13. “DOP Plan”: a date of purchase plan; which provides additional benefits during the Warranty Corp. of Canada, ULC, 421 7th Avenue S.W., Ste. -

Flight Centre Travel Group

Flight Centre Travel Group Feedback on Treasury Proposal Paper: “Reforms to the sale of add-on insurance products” September 2019 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Background on Flight Centre Group ................................................................................... 3 SECTION #1: Please provide evidence as to why a particular type of add-on insurance product should reside in a particular tier. ........................................................................... 5 1. Historically good value for money ....................................................................................... 5 1.1 Low value product, but with moderate complexity ......................................................................... 5 1.2 Overall distribution costs .................................................................................................................. 6 2. Strong competition ............................................................................................................. 7 2.1 The Travel Insurance Market in Australia ......................................................................................... 7 3. High risk of underinsurance ............................................................................................... 10 3.1 Personal Advice .............................................................................................................................. 10 3.2 Underinsurance ............................................................................................................................. -

KM Linking Agreement

LINKING AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE CITY OF GLENDALE, ARIZONA AND KONICA MINOLTA BUSINESS SOLUTIONS U.S.A., INC. THIS LINKING AGREEMENT (this “Agreement”) is entered into as of this day of , 20 , between the City of Glendale, an Arizona municipal corporation (the “City”), and Konica Minolta Business Solutions U.S.A, Inc., a(n) New York corporation authorized to do business in Arizona (“Contractor”), collectively, the “Parties.” RECITALS A. On January 29, 2021under Mohave Educational Services Cooperative Purchasing Agreement, the Mohave Educational Services Cooperative, Inc. entered into a contract with Contractor to purchase the goods and services described in the Digital Copiers, Multifunctional Devices, 3D Printers, Related Supplies, Maintenance and Managed Printer Services 20J-KMBS- 0129(“Cooperative Purchasing Agreement”), which is attached hereto as Exhibit A. The Cooperative Purchasing Agreement permits its cooperative use by other governmental agencies including the City. B. Section 2-149 of the City’s Procurement Code permits the Materials Manager to procure goods and services by participating with other governmental units in cooperative purchasing agreements when the best interests of the City would be served. C. Section 2-149 also provides that the Materials Manager may enter into such cooperative agreements without meeting the formal or informal solicitation and bid requirements of Glendale City Code Sections 2-145 and 2-146. D. The City desires to contract with Contractor for supplies or services identical, or nearly identical, to the supplies or services Contractor is providing other units of government under the Cooperative Purchasing Agreement. Contractor consents to the City’s utilization of the Cooperative Purchasing Agreement as the basis of this Agreement, and Contractor desires to enter into this Agreement to provide the supplies and services set forth in this Agreement. -

Terms and Conditions

TERMS AND CONDITIONS Polaris / Victory Motorcycles / Indian Motorcycle / Slingshot / GEM This Service Contract; including the terms, conditions, limitations, exceptions and exclusions, and the Declaration Page, constitute the entire agreement between Polaris Sales, Inc. and You (the purchaser) and no representation, promise or condition not contained herein shall modify these items; except as required by law. This Contract is not an insurance policy. The purchase of this Service Contract is not required to obtain financing or to purchase or lease a Vehicle. This Contract is not valid for any vehicles or equipment that is NOT sold by “Dealers” (as defined). DEFINITIONS: the following capitalized words have the stated meaning: “We”, “Us”, “Our”, “Obligor”, “Provider”, “Administrator”: the party or parties obligated to provide and administer service under this Service Contract as the service contract provider and administrator, Polaris Sales, Inc., 2100 Highway 55, Medina, MN 55340, TOLL-FREE 1-877-472-1372. (In CA: DMV Distributor License #60014. In OK & WY: Polaris Industries, Inc., 2100 Highway 55, Medina, MN 55340.) “Dealer”: the authorized Polaris/Victory/Indian/Slingshot/GEM motor Vehicle dealership that this Contract and the covered Vehicle were purchased from. “You”, “Your”: the purchaser of this Contract and Vehicle that is to receive coverage under this Service Contract. “Service Contract”, “Contract”: this Polaris Protection Plan that has been purchased for the Vehicle indicated on the Declaration Page. “Declaration Page”: the numbered document issued to You by the Dealer which must be attached to this Contract, and lists important information regarding You, the covered Vehicle, the Contract terms, conditions, and other vital information. -

USE of CAPTIVE INSURANCE in ESTATE and BUSINESS PLANNING by Gordon A

USE OF CAPTIVE INSURANCE IN ESTATE AND BUSINESS PLANNING by Gordon A. Schaller and Scott A. Harshman This article was published in ”Estate Planning”, September 1, 2008 Rising insurance costs coupled with increasing self-insured risk is a major issue faced by many businesses. In order to mitigate these risks, an increasing number of businesses are implementing captive insurance programs. A captive insurance company is a subsidiary or affiliate of the business entities that is formed to insure or reinsure the risks of those entities. Reasonable insurance premiums paid to a properly structured captive are deductible by the affiliated companies. Captive insurance companies are provided with special tax incentives so that their premium income may be non-taxable. This creates an exceptional opportunity for the owners of mid-market companies to transfer substantial wealth without gift, estate or generation- skipping tax consequences to the extent the captive insurance company is capitalized and owned by or in trust for younger generations. Captive ownership can also be structured to provide incentives for key management and business succession. These results are available by statute and IRS safe harbor rulings to carefully planned and implemented captives. This article will describe the Internal Revenue Code, case law and ruling requirements for a valid captive insurance company and focus on the estate and business planning opportunities that result. WHAT IS A CAPTIVE INSURANCE COMPANY? A captive insurance company is a corporation formed either in a U.S. or foreign jurisdiction for the purpose of writing property and casualty insurance to a small, usually related group of insureds.