Josephs of the Country: James Jones's Thirty-Year Men and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2Friday 1Thursday 3Saturday 4Sunday 5Monday 6Tuesday 7Wednesday 8Thursday 9Friday 10Saturday

JULY 2021 1THURSDAY 2FRIDAY DAYTIME THEME: DAYTIME THEME: TCM BIRTHDAY TRIBUTE: WILLIAM WYLER KEEPING THE KIDS BUSY PRIMETIME THEME: PRIMETIME THEME: SELVIS FRIDAY NIGHT NEO-NOIR Seeing Double 8:00 PM Harper (‘66) 8:00 PM Kissin’ Cousins (‘64) 10:15 PM Point Blank (‘67) 10:00 PM Double Trouble (‘67) 12:00 AM Warning Shot (‘67) 12:00 AM Clambake (‘67) 2:00 AM Live A Little, Love a Little (‘68) 3SATURDAY 4SUNDAY DAYTIME THEME: DAYTIME THEME: SATURDAY MATINEE HAPPY INDEPENDENCE DAY PRIMETIME THEME: PRIMETIME THEME: GABLE GOES WEST HAPPY INDEPENDENCE DAY 8:00 PM The Misfits (‘61) 8:00 PM Yankee Doodle Dandy (‘42) 10:15 PM The Tall Men (‘55) 10:15 PM 1776 (‘72) JULY JailhouseThes Stranger’s Rock(‘57) Return (‘33) S STAR OF THE MONTH: Elvis 5MONDAY 6TUESDAY 7WEDNESDAY P TCM SPOTLIGHT: Star Signs DAYTIME THEME: DAYTIME AND PRIMETIME THEME(S): DAYTIME THEME: MEET CUTES DAYTIME THEME: TY HARDIN TCM PREMIERE PRIMETIME THEME: SOMETHING ON THE SIDE PRIMETIME THEME: DIRECTED BY BRIAN DE PALMA PRIMETIME THEME: THE GREAT AMERICAN MIDDLE TWITTER EVENTS 8:00 PM The Bonfire of the Vanities (‘90) PSTAR SIGNS Small Town Dramas NOT AVAILABLE IN CANADA 10:15 PM Obsession (‘76) Fire Signs 8:00 PM Peyton Place (‘57) 12:00 AM Sisters (‘72) 8:00 PM The Cincinnati Kid (‘65) 10:45 PM Picnic (‘55) 1:45 AM Blow Out (‘81) (Steeve McQueen – Aries) 12:45 AM East of Eden (‘55) 4:00 AM Body Double (‘84) 10:00 PM The Long Long Trailer (‘59) 3:00 AM Kings Row (‘42) (Lucille Ball – Leo) 5:15 AM Our Town (‘40) 12:00 AM The Bad and the Beautiful (‘52) (Kirk Douglas–Sagittarius) -

13Th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture

13th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture James F. O’Gorman Non-fiction 38.65 ACROSS THE SEA OF GREGORY BENFORD SF 9.95 SUNS Affluent Society John Kenneth Galbraith 13.99 African Exodus: The Origins Christopher Stringer and Non-fiction 6.49 of Modern Humanity Robin McKie AGAINST INFINITY GREGORY BENFORD SF 25.00 Age of Anxiety: A Baroque W. H. Auden Eclogue Alabanza: New and Selected Martin Espada Poetry 24.95 Poems, 1982-2002 Alexandria Quartet Lawrence Durell ALIEN LIGHT NANCY KRESS SF Alva & Irva: The Twins Who Edward Carey Fiction Saved a City And Quiet Flows the Don Mikhail Sholokhov Fiction AND ETERNITY PIERS ANTHONY SF ANDROMEDA STRAIN MICHAEL CRICHTON SF Annotated Mona Lisa: A Carol Strickland and Non-fiction Crash Course in Art History John Boswell From Prehistoric to Post- Modern ANTHONOLOGY PIERS ANTHONY SF Appointment in Samarra John O’Hara ARSLAN M. J. ENGH SF Art of Living: The Classic Epictetus and Sharon Lebell Non-fiction Manual on Virtue, Happiness, and Effectiveness Art Attack: A Short Cultural Marc Aronson Non-fiction History of the Avant-Garde AT WINTER’S END ROBERT SILVERBERG SF Austerlitz W.G. Sebald Auto biography of Miss Jane Ernest Gaines Fiction Pittman Backlash: The Undeclared Susan Faludi Non-fiction War Against American Women Bad Publicity Jeffrey Frank Bad Land Jonathan Raban Badenheim 1939 Aharon Appelfeld Fiction Ball Four: My Life and Hard Jim Bouton Time Throwing the Knuckleball in the Big Leagues Barefoot to Balanchine: How Mary Kerner Non-fiction to Watch Dance Battle with the Slum Jacob Riis Bear William Faulkner Fiction Beauty Robin McKinley Fiction BEGGARS IN SPAIN NANCY KRESS SF BEHOLD THE MAN MICHAEL MOORCOCK SF Being Dead Jim Crace Bend in the River V. -

Throughout His Writing Career, Nelson Algren Was Fascinated by Criminality

RAGGED FIGURES: THE LUMPENPROLETARIAT IN NELSON ALGREN AND RALPH ELLISON by Nathaniel F. Mills A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor Alan M. Wald, Chair Professor Marjorie Levinson Professor Patricia Smith Yaeger Associate Professor Megan L. Sweeney For graduate students on the left ii Acknowledgements Indebtedness is the overriding condition of scholarly production and my case is no exception. I‘d like to thank first John Callahan, Donn Zaretsky, and The Ralph and Fanny Ellison Charitable Trust for permission to quote from Ralph Ellison‘s archival material, and Donadio and Olson, Inc. for permission to quote from Nelson Algren‘s archive. Alan Wald‘s enthusiasm for the study of the American left made this project possible, and I have been guided at all turns by his knowledge of this area and his unlimited support for scholars trying, in their writing and in their professional lives, to negotiate scholarship with political commitment. Since my first semester in the Ph.D. program at Michigan, Marjorie Levinson has shaped my thinking about critical theory, Marxism, literature, and the basic protocols of literary criticism while providing me with the conceptual resources to develop my own academic identity. To Patricia Yaeger I owe above all the lesson that one can (and should) be conceptually rigorous without being opaque, and that the construction of one‘s sentences can complement the content of those sentences in productive ways. I see her own characteristic synthesis of stylistic and conceptual fluidity as a benchmark of criticism and theory and as inspiring example of conceptual creativity. -

Palms to Pines Scenic Byway Corridor Management Plan

Palms to Pines Scenic Byway Corridor Management Plan PALMS TO PINES STATE SCENIC HIGHWAY CALIFORNIA STATE ROUTES 243 AND 74 June 2012 This document was produced by USDA Forest Service Recreation Solutions Enterprise Team with support from the Federal Highway Administration and in partnership with the USDA Forest Service Pacific Southwest Region, the Bureau of Land Management, the California Department of Transportation, California State University, Chico Research Foundation and many local partners. The USDA, the BLM, FHWA and State of California are equal opportunity providers and employers. In accordance with Federal law, U.S. Department of Agriculture policy and U.S. Department of Interior policy, this institution is prohibited from discriminating on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, age or disability. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (202) 720- 5964 (voice and TDD). Table of Contents Chapter 1 – The Palms to Pines Scenic Byway .........................................................................1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 1 Benefits of National Scenic Byway Designation .......................................................................... 2 Corridor Management Planning ................................................................................................. -

Elvis Quarterly 89 Ned

UEPS QUARTERLY 89 Driemaandelijks / Trimestriel januari-februari-maart 2009 / Afgiftekantoor Antwerpen X - erk. nr.: 708328 januari-februari-maart 2009 / Afgiftekantoor Antwerpen X - erk. nr.: Driemaandelijks / Trimestriel The United Elvis Presley Society is officieel erkend door Elvis en Elvis Presley Enterprises (EPE) sedert 1961 The United Elvis Presley Society Elvis Quarterly Franstalige afdeling: Driemaandelijks tijdschrift Jean-Claude Piret - Colette Deboodt januari-februari-maart 2009 Rue Lumsonry 2ème Avenue 218 Afgiftekantoor: Antwerpen X - 8/1143 5651 Tarcienne Verantwoordelijk uitgever: tel/fax 071 214983 Hubert Vindevogel e.mail: [email protected] Pijlstraat 15 2070 Zwijndrecht Rekeningnummers: tel/fax: 03 2529222 UEPS (lidgelden, concerten) e-mail: [email protected] 068-2040050-70 www.ueps.be TCB (boetiek): Voorzitter: 220-0981888-90 Hubert Vindevogel Secretariaat: Nederland: Martha Dubois Giro 2730496 (op naam van Hubert Vindevogel) IBAN: BE34 220098188890 – BIC GEBABEBB (boetiek) Medewerkers: IBAN: BE60 068204005070 – BIC GCCCBEBB (lidgelden – concerten) Tina Argyl Cecile Bauwens Showroom: Daniel Berthet American Dream Leo Bruynseels Dorp West 13 Colette Deboodt 2070 Zwijndrecht Pierre De Meuter tel: 03 2529089 (open op donderdag, vrijdag en zaterdag van 10 tot 18 uur Marc Duytschaever - Eerste zondag van elke maand van 13 tot 18 uur) Dominique Flandroit Marijke Lombaert Abonnementen België Tommy Peeters 1 jaar lidmaatschap: 18 € (vier maal Elvis Quarterly) Jean-Claude Piret 2 jaar: 32 € (acht maal Elvis Quarterly) Veerle -

New on DVD & Blu-Ray

New On DVD & Blu-Ray The Magnificent Seven Collection The Magnificent Seven Academy Award® Winner* Yul Brynner stars in the landmark western that launched the film careers of Steve McQueen, Charles Bronson and James Coburn. Tired of being ravaged by marauding bandits, a small Mexican village seeks help from seven American gunfighters. Set against Elmer Bernstein’s Oscar® Nominated** score, director John Sturges’ thrilling adventure belongs in any Blu-ray collection. Return of the Magnificent Seven Yul Brynner rides tall in the saddle in this sensational sequel to The Magnificent Seven! Brynner rounds up the most unlikely septet of gunfighters—Warren Oates, Claude Akins and Robert Fuller among them—to search for their compatriot who has been taken hostage by a band of desperados. Guns of the Magnificent Seven This fast-moving western stars Oscar® Winner* George Kennedy as the revered—and feared—gunslinger Chris Adams! When a Mexican revolutionary is captured, his associates hire Adams to break him out of prison to restore hope to the people. After recruiting six experts in guns, knives, ropes and explosives, Adams leads his band of mercenaries on an adventure that will pit them against their most formidable enemy yet! *1967: Supporting Actor, Cool Hand Luke. The Magnificent Seven Ride! This rousing conclusion to the legendary Magnificent Seven series stars Lee Van Cleef as Chris Adams. Now married and working for the law, Adams’ settled life is turned upside-down when his wife is killed. Tracking the gunmen, he finds a plundered border town whose widowed women are under attack by ruthless marauders. -

© Copyrighted by Charles Ernest Davis

SELECTED WORKS OF LITERATURE AND READABILITY Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Davis, Charles Ernest, 1933- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 07/10/2021 00:54:12 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/288393 This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 70-5237 DAVIS, Charles Ernest, 1933- SELECTED WORKS OF LITERATURE AND READABILITY. University of Arizona, Ph.D., 1969 Education, theory and practice University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan © COPYRIGHTED BY CHARLES ERNEST DAVIS 1970 iii SELECTED WORKS OF LITERATURE AND READABILITY by Charles Ernest Davis A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF SECONDARY EDUCATION In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY .In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 6 9 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE I hereby recommend that this dissertation prepared under my direction by Charles Ernest Davis entitled Selected Works of Literature and Readability be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy PqulA 1- So- 6G Dissertation Director Date After inspection of the final copy of the dissertation, the following members of the Final Examination Committee concur in its approval and recommend its acceptance:" *7-Mtf - 6 7-So IdL 7/3a This approval and acceptance is contingent on the candidate's adequate performance and defense of this dissertation at the final oral examination; The inclusion of this sheet bound into the library copy of the dissertation is evidence of satisfactory performance at the final examination. -

National Film Registry Titles Listed by Release Date

National Film Registry Titles 1989-2017: Listed by Year of Release Year Year Title Released Inducted Newark Athlete 1891 2010 Blacksmith Scene 1893 1995 Dickson Experimental Sound Film 1894-1895 2003 Edison Kinetoscopic Record of a Sneeze 1894 2015 The Kiss 1896 1999 Rip Van Winkle 1896 1995 Corbett-Fitzsimmons Title Fight 1897 2012 Demolishing and Building Up the Star Theatre 1901 2002 President McKinley Inauguration Footage 1901 2000 The Great Train Robbery 1903 1990 Life of an American Fireman 1903 2016 Westinghouse Works 1904 1904 1998 Interior New York Subway, 14th Street to 42nd Street 1905 2017 Dream of a Rarebit Fiend 1906 2015 San Francisco Earthquake and Fire, April 18, 1906 1906 2005 A Trip Down Market Street 1906 2010 A Corner in Wheat 1909 1994 Lady Helen’s Escapade 1909 2004 Princess Nicotine; or, The Smoke Fairy 1909 2003 Jeffries-Johnson World’s Championship Boxing Contest 1910 2005 White Fawn’s Devotion 1910 2008 Little Nemo 1911 2009 The Cry of the Children 1912 2011 A Cure for Pokeritis 1912 2011 From the Manger to the Cross 1912 1998 The Land Beyond the Sunset 1912 2000 Musketeers of Pig Alley 1912 2016 Bert Williams Lime Kiln Club Field Day 1913 2014 The Evidence of the Film 1913 2001 Matrimony’s Speed Limit 1913 2003 Preservation of the Sign Language 1913 2010 Traffic in Souls 1913 2006 The Bargain 1914 2010 The Exploits of Elaine 1914 1994 Gertie The Dinosaur 1914 1991 In the Land of the Head Hunters 1914 1999 Mabel’s Blunder 1914 2009 1 National Film Registry Titles 1989-2017: Listed by Year of Release Year Year -

KIPLING JOURNAL 1 2 KIPLING JOURNAL June 2007 June 2007 KIPLING JOURNAL 3

June 2007 KIPLING JOURNAL 1 2 KIPLING JOURNAL June 2007 June 2007 KIPLING JOURNAL 3 THE KIPLING SOCIETY Registered Charity No. 278885 PRESIDENT Sir George Engle, K.C.B., Q.C. PAST PRESIDENT Dr Michael G. Brock, C.B.E. VICE-PRESIDENTS Joseph R. Dunlap, D.L.S. Mrs Margaret Newsom Mrs L.A.F. Lewis Professor Thomas Pinney, Ph.D. Mrs Rosalind Kennedy Mrs Anne Shelford J.H. McGivering, R.D. J.W. Michael Smith David Alan Richards G.H. Webb, C.M.G., O.B.E COUNCIL: ELECTED AND CO-OPTED MEMBERS John Radcliffe (Chairman) Robin Mitchell Cdr Alastair Wilson (Deputy Chairman) Bryan Diamond Dr Mary Hamer Sharad Keskar Ms Anne Harcombe COUNCIL: HONORARY OFFICE-BEARERS Lt-Colonel R.C. Ayers, O.B.E. (Membership Secretary) [his e-mail address is: [email protected]] Frank Noah (Treasurer) Jane Keskar (Secretary) [her address is: 6 Clifton Road, London W9 1SS; Tel & Fax 020 7286 0194; her e-mail address is: [email protected]] Andrew Lycett (Meetings Secretary) Sir Derek Oulton, G.C.B., Q.C. (Legal Adviser) John Radcliffe (On Line Editor) [his e-mail address is: [email protected]] John Walker (Librarian) Roy Slade (Publicity Officer) David Page, B.Sc. (Editor, Kipling Journal) [his e-mail address is: [email protected]] Independent Financial Examiner Professor G.M. Selim, M.Com., Ph.D., F.I.I.A. THE SOCIETY'S ADDRESS Postal: 6 Clifton Road, London W9 1SS; Web-site: www.kipling.org.uk Fax: 020 7286 0194 THE SOCIETY'S NORTH AMERICAN REPRESENTATIVE David Alan Richards, 18 Forest Lane, Scarsdale, New York, NY 10583, U.S.A. -

2009 RHODE ISLAND INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL MEDIA RELEASE for Details, Photographs Or Videos About RIIFF News Releases, Contact: Adam M.K

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: 2009 RHODE ISLAND INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL MEDIA RELEASE For Details, Photographs or Videos about RIIFF News Releases, Contact: Adam M.K. Short, Producing Director [email protected] • 401.861-4445 ERNEST BORGNINE TO RECEIVE 2009 LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARD AT RHODE ISLAND INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL ACADEMY AWARD-WINNING ACTOR TO BE HONORED AT FESTIVAL’S 13TH YEAR CELEBRATION ON FRIDAY, AUGUST 7TH (PROVIDENCE, RI) Ernest Borgnine, who won the 1955 best actor Academy Award for his performance as a lovelorn butcher in the film “Marty” and is better known to a later generation of television viewers as the PT-boat skipper on “McHale’s Navy,” will receive a Lifetime Achievement award at this year’s Rhode Island International Film Festival (RIIFF) in early August. The award will be presented at the world premiere screening of his most recent film, director Greg Swartz's “Another Harvest Moon,” on Friday, August 7th at 7:00 p.m. The location for the screening will be the Columbus Theatre Arts Center at 270 Broadway. Tickets for this special event are $15.00 and can be purchased online at the Festival’s website: http://www.film-festival.org/Borgnine.php “Presenting Mr. Borgnine with the RIIFF Lifetime Achievement Award is deeply heartfelt for us at the Festival,” commented RIIFF’s Executive Director George T. Marshall. “He is such an amazingly accomplished actor; we are deeply honored to have him participate in this year’s event. His work has touched millions and set new standards; becoming a vibrant and critical part of the American experience.” Previous winners of the RIIFF Lifetime Achievement Award have been director Blake Edwards; actresses Cicely Tyson and Patricia Neal; and actors Seymour Cassel and Kim Chan. -

THE JAMES JONES LITERARY SOCIETY NEWSLETTER on the Trail of Jones and Prewitt in Hawaii

THE JAMES JONES LITERARY SOCIETY NEWSLETTER Vol. 10, No. 3, Spring, 2001 Editor Thomas J. Wood Editorial Advisory Board Dwight Connelly Kevin Heisler Richard King Michael Mullen The James Jones Society Newsletter is published quarterly to keep members and interested parties apprised of activities, projects and upcoming events of the Society; to promote public interest and academic research in the works of James Jones; and to celebrate his memory and legacy. Submissions of essays, features, anecdotes, photographs, etc., that pertain to author James Jones may be sent to the editor for publication consideration. Every attempt will be made to return material, if requested upon submission. Material may be edited for length, clarity and accuracy. Send submissions to: Thomas J. Wood Archives/Special Collections, LIB 144 University of Illinois at Springfield P.O. Box 19243 Springfield, IL, 62794-9423 [email protected]. Writers guidelines available upon request and online. The James Jones Literary Society http://jamesjoneslitsociety.vinu.edu/ Online information about the James Jones First Novel Fellowship http://wilkes.edu/~english/jones.html On the Trail of Jones and Prewitt in Hawaii: JJLS Members Becker and Thobaben Recreate their Kolekole Hike [Carl Becker and Robert Thobaben are veterans of the Pacific Theater in WWII and now teach at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio. They first recreated Robert E. Lee Prewitt's fictional hike to Oahu's Kolekole Pass in 1991. Earlier this year they again made the hike. Here is Carl Becker's account of their adventure. - ed.] As many members of the Society know, Bob Thobaben and I went to Schofield Barracks in Oahu in the Hawaiian Islands in 1991 and there recreated Robert E. -

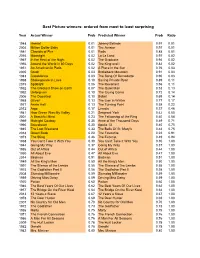

Best Picture Winners: Ordered from Most to Least Surprising

Best Picture winners: ordered from most to least surprising Year Actual Winner Prob Predicted Winner Prob Ratio 1948 Hamlet 0.01 Johnny Belinda 0.97 0.01 2004 Million Dollar Baby 0.01 The Aviator 0.97 0.01 1981 Chariots of Fire 0.01 Reds 0.88 0.01 2016 Moonlight 0.02 La La Land 0.97 0.02 1967 In the Heat of the Night 0.02 The Graduate 0.94 0.02 1956 Around the World in 80 Days 0.02 The King and I 0.82 0.02 1951 An American in Paris 0.02 A Place in the Sun 0.76 0.03 2005 Crash 0.03 Brokeback Mountain 0.91 0.03 1943 Casablanca 0.03 The Song Of Bernadette 0.90 0.03 1998 Shakespeare in Love 0.10 Saving Private Ryan 0.89 0.11 2015 Spotlight 0.06 The Revenant 0.56 0.11 1952 The Greatest Show on Earth 0.07 The Quiet Man 0.53 0.13 1992 Unforgiven 0.10 The Crying Game 0.72 0.14 2006 The Departed 0.10 Babel 0.69 0.14 1968 Oliver! 0.13 The Lion in Winter 0.77 0.17 1977 Annie Hall 0.13 The Turning Point 0.58 0.22 2012 Argo 0.17 Lincoln 0.37 0.46 1941 How Green Was My Valley 0.21 Sergeant York 0.42 0.50 2001 A Beautiful Mind 0.23 The Fellowship of the Ring 0.40 0.58 1969 Midnight Cowboy 0.35 Anne of the Thousand Days 0.49 0.71 1995 Braveheart 0.30 Apollo 13 0.40 0.75 1945 The Lost Weekend 0.33 The Bells Of St.