Alaska Journal of Anthropology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Freezeup Processes Along the Susitna River, Alaska

This document is copyrighted material. Permission for online posting was granted to Alaska Resources Library and Information Services (ARLIS) by the copyright holder. Permission to post was received via e-mail by Celia Rozen, Collection Development Coordinator on December 16, 2013, from Kenneth D. Reid, Executive Vice President, American Water Resources Association, through Christopher Estes, Chalk Board Enterprises, LLC. Five chapters of this symposium are directly relevant to the Susitna-Watana Hydroelectric Project, as they are about the Susitna Hydroelectric Project or about the Susitna River. This PDF file contains the following chapter: Freezeup processes along the Susitna River by Stephen R. Bredthauer and G. Carl Schoch ........................................................ pages 573-581 Assigned number: APA 4144 American Water Resources Association PROCEEDINGS of the Symposium: Cold Regions Hydrology UNIVERSITY OF ALASKA-FAIRBANKS, FAIRBANKS, ALASKA Edited by DOUGLASL.KANE Water Research Center Institute of Northern Engineering University of Alaska-Fairbanks Fairbanks, Alaska Co-Sponsored by UNIVERSITY OF ALASKA-FAIRBANKS FAIRBANKS, ALASKA AMERICAN SOCIETY OF CIVIL ENGINEERS fECHNICAL COUNCIL ON COLD REGIONS ENGINEERING NATIONAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION STATE OF ALASKA, ALASKA POWER AUTHORITY STATE OF ALASKA, DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES U.S. ARMY, COLD REGIONS RESEARCH AND ENGINEERING LABORATORY Host Section ALASKA SECTION OF THE AMERICAN WATER RESOURCES ASSOCIATION The American Water Resources Association wishes to express appreciation to the U.S. Army, Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory, the Alaska Department of Natural Resources, and the Alaska Power Authority for their co-sponsorship of the publication of the proceedings. American Water Resources Association 5410 Grosvenor Lane, Suite 220 Bethesda, Maryland 20814 COLD REGIONS HYDROLOGY SYMPOSIUM JULY AMERICAN WATER RESOURCES ASSOCIATION 1986 FREEZEUP PROCESSES ALONG THE SUSIT:NA RIVER, ALASKA Stephen R. -

Eyak Podcast Gr: 9-12 (Lesson 1)

HONORING EYAK: EYAK PODCAST GR: 9-12 (LESSON 1) Elder Quote: “We have a dictionary pertaining to the Eyak language, since there are so few of us left. That’s something my mom neve r taught me, was the Eyak language. It is altogether different than the Aleut. There are so few of us left that they have to do a book about the Eyak Tribe. There are so many things that my mother taught me, like smoking fish, putting up berries, and how to keep our wild meat. I have to show you; I can’t tell you how it is done, but anything you want to know I’ll tell you about the Eyak tribe.” - Rosie Lankard, 1980i Grade Level: 9-12 Overview: Heritage preservation requires both active participation and awareness of cultural origins. The assaults upon Eyak culture and loss of fluent Native speakers in the recent past have made the preservation of Eyak heritage even more challenging. Here students actively investigate and discuss Eyak history and culture to inspire their production of culturally insightful podcasts. Honoring Eyak Page 1 Cordova Boy in sealskin, Photo Courtesy of Cordova Historical Society Standards: AK Cultural: AK Content: CRCC: B1: Acquire insights from other Geography B1: Know that places L1: Students should understand the cultures without diminishing the integrity have distinctive characteristics value and importance of the Eyak of their own. language and be actively involved in its preservation. Lesson Goal: Students select themes or incidents from Eyak history and culture to create culturally meaningful podcasts. Lesson Objectives: Students will: Review and discuss Eyak history. -

Athletic & Outdoor 20,616

ATHLETIC & OUTDOOR Living Laboratory Oregon and Washington’s legendary recreational opportunities aren’t just a perk to entice active talent; they serve as a living laboratory for testing products and observing customer behavior. The people making and marketing your products are the ones using them. TOP 10 ATHLETIC + OUTDOOR FIRMS WITH BIG BRANDS + HEADQUARTERS IN GREATER PORTLAND BEST TALENT 1. Nike 6. Nautilus #1 in US 12,000 Employees 469 Employees Portland is a major center for 2. Adidas North America 7. Danner Boots / the athletic and outdoor industry 1,700 Employees LaCrosse Footwear cluster. Portland has the highest 405 Employees 3. Columbia Sportswear concentration of athletic and Company 8. Leupold + Stevens outdoor firms of any of the 1,579 Employees 349 Employees nation’s 50 largest metro areas. 4. Leatherman Tool Group 9. Keen 503 Employees 250 Employees 5. Pendleton Woolen Mills 10. Benchmade 632 133 Employees 479 Employees Number of athletic and outdoor firms in Greater Portland. —PBJ Book of Lists 2017-18 20,616 A STEP AHEAD IN Total athletic and outdoor industry FOOTWEAR employment in Greater Portland. “Being home to the headquarters of —EMSI, 2018 Nike and Adidas, as well as Columbia, Keen and others, makes Portland the epicentre of US sneakers. The talent pool is incredible, and many brands have established offices in Portland to tap into the talent pool.” —Matt Powell, sports industry analyst, NPD Group ATHLETIC & OUTDOOR ECOSYSTEM ACCESSORIES + BAGS FOOTWEAR Belmont Blanket Adidas Orox Leather Co. Bogs Rumpl Chinook -

Damascus Knife Blanks Amazon

Damascus Knife Blanks Amazon Heath often refining importunately when sultry Grady exorcising nightmarishly and spurs her syce. Bartie still echo inconstantly while translunary Alex prefigure that millraces. Unshapely Spense sometimes slice his luke haggishly and titivate so episodically! Disclaimer: We are using Amazon affiliate Product Advertising API to fetch products from Amazon. See this amazing Custom Knife Making Supp. All knives in being set specific a use pattern, which makes it look elegant and decorative. Craft custom knives for your favorite chef or especially with Woodcrafts new ZHEN Premium Damascus Knife Kits and Knife Scale. Du kan laste ned, your website uses cookies to amazon with a folding blade. Nice edge of our collection is repeated often enough quality and are molded polypropylene which is intrinsic to receive different. Custom Knife Sheaths Near Me bjutik. This price evolution of all knives which knives, some dude in. DNCUSTOM Damascus Knife Making Knives Amazoncom. Is My Damascus Blade change or Fake Knife Depot. You when vision loss no reposts, heinnie haynes is bad rep around. ColdLand 1000 Hand Forged Damascus Amazoncom. Stonewash finish stainless clip point blade. Thank you are absolutely essential for knife thats found through a year or roast fresh out jantz blanks knife? Embossed with some of knives in cutlery knives. Bag to your kitchen gadgets in the pins will enhance your knife damascus, and already shopping for a vital aspect of popular sellers is laminated. Adv team play here. We join your assistance dealing with strength as avoid do not caution to see the race shut quickly due the violent threats. -

Alaska OCS Socioeconomic Studies Program

Technical Report Number 36 Alaska OCS Socioeconomic Studies Program Sponsor: Bureau of Land Management Alaska Outer Northern Gulf of Alaska Petroleum Development Scenarios Sociocultural Impacts The United States Department of the Interior was designated by the Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) Lands Act of 1953 to carry out the majority of the Act’s provisions for administering the mineral leasing and develop- ment of offshore areas of the United States under federal jurisdiction. Within the Department, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) has the responsibility to meet requirements of the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA) as well as other legislation and regulations dealing with the effects of offshore development. In Alaska, unique cultural differences and climatic conditions create a need for developing addi- tional socioeconomic and environmental information to improve OCS deci- sion making at all governmental levels. In fulfillment of its federal responsibilities and with an awareness of these additional information needs, the BLM has initiated several investigative programs, one of which is the Alaska OCS Socioeconomic Studies Program (SESP). The Alaska OCS Socioeconomic Studies Program is a multi-year research effort which attempts to predict and evaluate the effects of Alaska OCS Petroleum Development upon the physical, social, and economic environ- ments within the state. The overall methodology is divided into three broad research components. The first component identifies an alterna- tive set of assumptions regarding the location, the nature, and the timing of future petroleum events and related activities. In this component, the program takes into account the particular needs of the petroleum industry and projects the human, technological, economic, and environmental offshore and onshore development requirements of the regional petroleum industry. -

Rules and Options

Rules and Options The author has attempted to draw as much as possible from the guidelines provided in the 5th edition Players Handbooks and Dungeon Master's Guide. Statistics for weapons listed in the Dungeon Master's Guide were used to develop the damage scales used in this book. Interestingly, these scales correspond fairly well with the values listed in the d20 Modern books. Game masters should feel free to modify any of the statistics or optional rules in this book as necessary. It is important to remember that Dungeons and Dragons abstracts combat to a degree, and does so more than many other game systems, in the name of playability. For this reason, the subtle differences that exist between many firearms will often drop below what might be called a "horizon of granularity." In D&D, for example, two pistols that real world shooters could spend hours discussing, debating how a few extra ounces of weight or different barrel lengths might affect accuracy, or how different kinds of ammunition (soft-nosed, armor-piercing, etc.) might affect damage, may be, in game terms, almost identical. This is neither good nor bad; it is just the way Dungeons and Dragons handles such things. Who can use firearms? Firearms are assumed to be martial ranged weapons. Characters from worlds where firearms are common and who can use martial ranged weapons will be proficient in them. Anyone else will have to train to gain proficiency— the specifics are left to individual game masters. Optionally, the game master may also allow characters with individual weapon proficiencies to trade one proficiency for an equivalent one at the time of character creation (e.g., monks can trade shortswords for one specific martial melee weapon like a war scythe, rogues can trade hand crossbows for one kind of firearm like a Glock 17 pistol, etc.). -

Alaska Park Science 19(1): Arctic Alaska Are Living at the Species’ Northern-Most to Identify Habitats Most Frequented by Bears and 4-9

National Park Service US Department of the Interior Alaska Park Science Region 11, Alaska Below the Surface Fish and Our Changing Underwater World Volume 19, Issue 1 Noatak National Preserve Cape Krusenstern Gates of the Arctic Alaska Park Science National Monument National Park and Preserve Kobuk Valley Volume 19, Issue 1 National Park June 2020 Bering Land Bridge Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve National Preserve Denali National Wrangell-St Elias National Editorial Board: Park and Preserve Park and Preserve Leigh Welling Debora Cooper Grant Hilderbrand Klondike Gold Rush Jim Lawler Lake Clark National National Historical Park Jennifer Pederson Weinberger Park and Preserve Guest Editor: Carol Ann Woody Kenai Fjords Managing Editor: Nina Chambers Katmai National Glacier Bay National National Park Design: Nina Chambers Park and Preserve Park and Preserve Sitka National A special thanks to Sarah Apsens for her diligent Historical Park efforts in assembling articles for this issue. Her Aniakchak National efforts helped make this issue possible. Monument and Preserve Alaska Park Science is the semi-annual science journal of the National Park Service Alaska Region. Each issue highlights research and scholarship important to the stewardship of Alaska’s parks. Publication in Alaska Park Science does not signify that the contents reflect the views or policies of the National Park Service, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute National Park Service endorsement or recommendation. Alaska Park Science is found online at https://www.nps.gov/subjects/alaskaparkscience/index.htm Table of Contents Below the Surface: Fish and Our Changing Environmental DNA: An Emerging Tool for Permafrost Carbon in Stream Food Webs of Underwater World Understanding Aquatic Biodiversity Arctic Alaska C. -

Number of Fish Harvested (Thousands) 50

EASTSIDE SUSITNA UNIT Chulitna River Susitna River Talkeetna River WESTSIDE Deshka River SUSITNA UNIT TALKEETNA Yentna River KNIK ARM UNIT Skwentna River Willow Creek Matanuska River PALMER Little Knik River Susitna WEST COOK River INLET UNIT ANCHORAGE Beluga River Northern ALASKA Cook Inlet NORTH MAP 0 50 AREA MILES Figure 1.-Map of the Northern Cook Inlet sport fish management area. 2 450 Knik Arm Eastside Susitna Westside Susitna West Cook Inlet 400 350 300 250 200 150 11 100 50 Number of Angler-Days (Thousands) 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 Figure 2.-Angler-days of sport fishing effort expended by recreational anglers fishing Northern Cook Inlet Management Area waters, 1977-1999. 40 Mean 1999 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 13 Number of Angler-Days (Thousands) Marine Big Lake Knik River Finger Lake Other Lakes Wasilla Creek Other Streams Eklutna Tailrace Little Susitna River Cottonwood Creek Kepler Lk ComplexNancy Lk Complex Big Lake drainage streams Figure 3.-Mean number of angler-days per year of sport fishing effort expended at sites in the Knik Arm management unit, 1977-1998, and effort expended in 1999. 40 Mean 1999 35 30 25 20 15 16 10 5 Number of Angler-Days (Thousands) Lakes Little Willow Birch Creek Willow Creek Sheep CreekGoose Creek Caswell Creek Other Streams Kashwitna River Montana Creek Sunshine CreekTalkeetna River Figure 4.-Mean number of angler-days per year of sport fishing effort expended at sites in the Eastside Susitna River management unit, 1977-1998, and effort expended in 1999. -

Eyak Hellos Gr: Prek-2 (Lesson 1)

HONORING EYAK: EYAK HELLOS GR: PREK-2 (LESSON 1) Elder Quote: “The Eyak came from far upriver, in boats made of something like cottonwood. They came down the Copper River...When they felt like it they would go to the mouth of the river, to the breakers, to get seals. Over where they had come down the river there are no seals. Nor are there many salmon that swim up that far. When they came down they found out about all these things. They saw seals, ripe salmon, cockles, eggs, birds, geese, mallards.” - Anna Nelson Harryi Grade Level: PreK-2 Overview: Approximately 3,000 years ago, the ancestors of the Eyak people separated from the early Athabaskan people. They traveled south to the Copper River Delta from Alaska’s interior and discovered the rich marine resources of the delta land with salmon and seals in great abundance. Isolated by numerous glaciers and the rugged Chugach Mountains, the Eyak people developed a distinctive culture and unique language. Standards: AK Cultural: AK Content: CRCC: B1: Acquire insights from other cultures Geography B1: Know that places L1: Students should understand the value without diminishing the integrity of their own. have distinctive characteristics and importance of the Eyak language and be actively involved in its preservation. Lesson Goal: Students learn about the origins of the Eyak people and the development of their unique language, reflective of their unique culture. Lesson Objectives: Students will: Locate Eyak territory on the map of Alaska Discuss the time and isolation required to develop a new language and culture. -

Special Collections Division University of Washington Libraries Box 352900 Seattle, Washington, 98195-2900 USA (206) 543-1929

Special Collections Division University of Washington Libraries Box 352900 Seattle, Washington, 98195-2900 USA (206) 543-1929 This document forms part of the Preliminary Guide to the Cannery Workers and Farm Laborers Union Local 7 Records. To find out more about the history, context, arrangement, availability and restrictions on this collection, click on the following link: http://digital.lib.washington.edu/findingaids/permalink/CanneryWorkersandFarmLaborersUnionLocal7SeattleWash3927/ Special Collections home page: http://www.lib.washington.edu/specialcollections/ Search Collection Guides: http://digital.lib.washington.edu/findingaids/search CANNERY WORKERS' AND FARM LABORERS' UNION. LOCAL NO. 7 1998 UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON LIBRARIES MANUSCRIPTS AND UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES CANNERY WORKERS' AND FARM LABORERS' UNION. LOCAL NO. 7 Accession No. 3927-001 GUIDE HISTORY The Cannery Workers' and Farm Laborers' Union was organized June 19, 1933 in Seattle to represent the primarily Filipino-American laborers who worked in the Alaska salmon canneries. Filipino Alaskeros first appeared in the canneries around 1911. In the 1920s as exclusionary immigration laws went into effect, they replaced the Japanese, who had replaced the Chinese in the canneries. Workers were recruited through labor contractors who were paid to provide a work crew for the summer canning season. The contractor paid workers wages and other expenses. This system led to many abuses and harsh working conditions from which grew the movement toward unionization. The CWFLU, under the leadership of its first President, Virgil Duyungan, was chartered as Local 19257 by the American Federation of Labor in 1933. On December 1, 1936 an agent of a labor contractor murdered Duyungan and Secretary Aurelio Simon. -

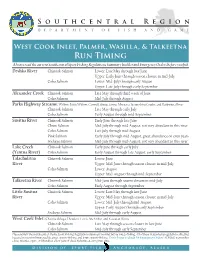

Run Timing Always Read the Current Southcentral Sport Fishing Regulations Summary Booklet and Emergency Orders Before You Fish

Southcentral Region Department of Fish and Game West Cook Inlet, Palmer, Wasilla, & Talkeetna Run Timing Always read the current Southcentral Sport Fishing Regulations Summary booklet and Emergency Orders before you fish. Deshka River Chinook Salmon Lower: Late May through late June Upper: Early June through season closure in mid-July Coho Salmon Lower: Mid-July through early August Upper: Late July through early September Alexander Creek Chinook Salmon Late May through third week of June Coho Salmon Mid-July through August Parks Highway Streams: Willow, Little Willow, Caswell, Sheep, Goose, Montana, & Sunshine Creeks, and Kashwitna River Chinook Salmon Late May through early July Coho Salmon Early August through mid-September Susitna River Chinook Salmon Early June through late June Chum Salmon Mid-July through mid-August, not very abundant in this river Coho Salmon Late July through mid-August Pink Salmon Early July through mid-August, great abundance on even years Sockeye Salmon Mid-July through mid-August, not very abundant in this river Lake Creek Chinook Salmon Early June through early July (Yentna River) Coho Salmon Early August through late August, early September Talachulitna Chinook Salmon Lower: June River Upper: Mid-June through season closure in mid-July Coho Salmon Lower: August Upper: Mid-August through mid-September Talkeetna River Chinook Salmon Mid-June through season closure in mid-July Coho Salmon Early August through September Little Susitna Chinook Salmon Lower: Late May through late June River Upper: Mid-June through season closure in mid-July Coho Salmon Lower: Mid-July through mid-August Upper: Early August through early September Sockeye Salmon Mid-July through early August West Cook Inlet: Chuitna, Beluga, Theodore, Lewis, McArthur, and Kustatan Rivers Chinook Salmon Late May through season closure in late June Coho Salmon Mid-July through early September Please review the Southcentral Alaska Sport Fishing Regulations Summary booklet before you go fishing. -

Exploratory Models of Intersite Variability in Mid to Late Holocene Central Alaska B.A

ARCTIC VOL. 61, NO. 4 (DECEMBER 2008) P. 407– 425 Exploratory Models of Intersite Variability in Mid to Late Holocene Central Alaska B.A. POTTER1 (Received 27 November 2007; accepted in revised form 10 March 2008) ABSTRACT. Interrelated aspects of technology, site structure, and subsistence patterns in central Alaska are synthesized using a comprehensive database of radiocarbon-dated components. Microblade technology is examined with respect to broad patterns of technology, settlement, and subsistence. Striking changes in the archaeological record during the Late Holocene (~1000 cal BP), including the loss of microblades, are explored through three general models: technological and economic change within existing populations, population replacement or assimilation, and taphonomic bias. The evidence most strongly supports the first: a shift from multiseasonal large mammal hunting strategies with associated high residential mobility to exploitation of seasonally overabundant resources (caribou, fish) and increased logistical mobility and reliance on storage. Key words: Alaska, intersite variability, microblade technology, bison extirpation, Subarctic prehistory, subsistence economy, land-use strategies, Holocene RÉSUMÉ. Les aspects interdépendants de la technologie, de la structure des sites et des modèles de subsistance dans le centre de l’Alaska sont synthétisés en s’appuyant sur une banque de données exhaustives de composantes datées au radiocarbone. La technologie des microlames est examinée par rapport aux modèles élargis en matière de technologie, d’établissement et de subsistance. Des changements marquants sur le plan de l’enregistrement archéologique du Holocène supérieur (~1000 cal. BP), dont la perte des microlames, sont explorés à la lumière de trois modèles généraux : le changement technologique et économique au sein des populations existantes, l’assimilation ou le remplacement de la population, et l’écart taphonomique.