Early Modern Japan 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Waya&R People Do Their

THE MOST TRUSTED NAME IN RADIO ISSUE 1985 DECEMBER 17 1993 This Week The future is in your hands. At least, i:'s the future as a group of record executives, along with a gaggle of Gavin types, see it. Hey, if Jeane Dixon and the Amazing Peskin can do it, why can't we? And so we get the jump on '94 from Craig LAW! (above), who sees less virtual "I predict that the reality than simple reality com- ing to the music business. On the GAVIN side of the crystal hall, Album Adult Alternative CEO David Dalton sees and hears free -form radio in the new year-or he'll reduce subscrip- tion rates (Just kidding!). And format will change the Ron Fel has a disturbing vision about Billy Joel wayA&R people do their (right). Our Newss.ection is given cver to a wrap-up of a o G.qey'll be ableto phat and crazy year, as managing editor Ben Fong -Torres steals liberally from ook at a4C 50year hisrootsgROMMIlle(which or stole liberally from Esquire) to do the honors. Re -live such great moments as Prince's old artist and think earth -shaking name change and a certa n pretty woman making Lyle Lovett (below) an honest man. F nally, we predict a sea- about workIng with sonal feature in the Gavin Yellow Pages them." of Radio, as Natalie Duitsman canvasses THESE AND OTHER PREDICTIONS, several radio stations- MINX-Amherst, Mass., WHAI- Greenfield, Mass., and Live 105 - BY RECORD INDUSTRY SEERS, ARE San Francisco-to learn how they handle Christmas music. -

Planet Earth R Eco.R Din Gs

$4.95 (U.S.), $5.95 (CAN.), £3.95 (U.K.) IN THE NEWS ******** 3 -DIGIT 908 1B)WCCVR 0685 000 New Gallup Charts Tap 1GEE4EM740M09907411 002 BI MAR 2396 1 03 MON1 Y GREENLY U.K. Indie Dealers ELM AVE APT A 3740 PAGE LONG BEACH, CA 90807 -3402 8 Gangsta Lyric Ratings Discussed At Senate Hearing On Rap PAGE 10 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC, VIDEO AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT MARCH 5, 1994 ADVERTISEMENTS MVG's Clawfinger Grammy Nominations Spur Publicity Blitz Digs Into Europe Labels Get Aggressive With Pre Award Ads BY THOM DUFFY BY DEBORAH RUSSELL Clapton, and k.d. lang experienced draw some visibility to your artists." major sales surges following Gram- A &M launched a major television STOCKHOLM -The musical LOS ANGELES -As the impact of my wins, but labels aren't waiting for advertising campaign in late Febru- rage of Clawfinger, a rock-rap the Grammys on record sales has be- the trophies anymore. Several compa- ary to promote Sting's "Ten Sum- band hailing from Sweden, has come more evident nies have kicked off aggressive ad- moner's Tales," (Continued on page 88) in recent years, vertising and promotional campaigns which first ap- nominations, as touting their nominees for the March peared on The Bill- well as victories, 1 awards. board 200 nearly a have become valu- Says A &M senior VP of sales and year ago. Sting is able marketing distribution Richie Gallo, "It would the top- nominated evil oplriin tools for record seem that people are being more ag- artist in the 36th companies. -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A. -

The Blue Book of the General Convention Contains the Reports to the Church of the Committees, Commissions, Agencies and Boards (Ccabs) of the General Convention

Easter 2012 To: The Bishops and Deputies of the 77th General Convention of the Episcopal Church From: (The Rev’d Dr.) Gregory Straub, Executive Officer & Secretary Greetings! Here is your long-awaited reading in preparation for the 77th General Convention of the Episcopal Church, which will convene in Indianapolis, Indiana, on July 5, 2012. The Blue Book of the General Convention contains the reports to the church of the Committees, Commissions, Agencies and Boards (CCABs) of the General Convention. (The book is salmon this year, for no better reason than I like it.) For the past three years more than 500 of our fellow church members, bishops, priests, deacons and lay persons, have volunteered their time and energy to address resolutions referred to them by the 76th General Convention and to investigate, as well, areas of concern denoted in their canonical or authorizing mandates. I urge you to read the Blue Book in its entirety in preparation for our work in Indianapolis. (Diocesan deputations may wish to apportion sections of the Blue Book among their members and allow one deputy or alternate to be the resource person for a given area.) Not only will you find the reports of the CCABs contained herein, but also their resolutions (“A” resolutions). A PDF version is available for free download from the General Convention website, and the General Convention Office’s publisher, Church Publishing, is offering for sale printed volumes and e-book versions on the Church Publishing website. (The 76th General Convention did not authorize the funds for sending printed volumes to each bishop, deputy, registered alternate and registered visitor, as in the past, but I hope you find the formats offered sufficient for your use.) Also available on the General Convention website is Executive Council’s draft proposed budget, which will serve as the basis for the Joint Standing Committee on Program, Budget & Finance’s work on its proposed budget, which it will present at a joint session of the General Convention on July 10. -

The Book of Common Prayer

The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church Together with The Psalter or Psalms of David According to the use of The Episcopal Church Church Publishing Incorporated, New York Certificate I certify that this edition of The Book of Common Prayer has been compared with a certified copy of the Standard Book, as the Canon directs, and that it conforms thereto. Gregory Michael Howe Custodian of the Standard Book of Common Prayer January, 2007 Table of Contents The Ratification of the Book of Common Prayer 8 The Preface 9 Concerning the Service of the Church 13 The Calendar of the Church Year 15 The Daily Office Daily Morning Prayer: Rite One 37 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite One 61 Daily Morning Prayer: Rite Two 75 Noonday Prayer 103 Order of Worship for the Evening 108 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite Two 115 Compline 127 Daily Devotions for Individuals and Families 137 Table of Suggested Canticles 144 The Great Litany 148 The Collects: Traditional Seasons of the Year 159 Holy Days 185 Common of Saints 195 Various Occasions 199 The Collects: Contemporary Seasons of the Year 211 Holy Days 237 Common of Saints 246 Various Occasions 251 Proper Liturgies for Special Days Ash Wednesday 264 Palm Sunday 270 Maundy Thursday 274 Good Friday 276 Holy Saturday 283 The Great Vigil of Easter 285 Holy Baptism 299 The Holy Eucharist An Exhortation 316 A Penitential Order: Rite One 319 The Holy Eucharist: Rite One 323 A Penitential Order: Rite Two 351 The Holy Eucharist: Rite Two 355 Prayers of the People -

Executive of the Week: Atlantic Records GM/Senior VP Urban A&R Lanre Gaba

BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE APRIL 13, 2020 | PAGE 4 OF 19 ON THE CHARTS JIM ASKER [email protected] Bulletin SamHunt’s Southside Rules Top Country YOURAlbu DAILYms; BrettENTERTAINMENT Young ‘Catc NEWSh UPDATE’-es Fifth AirplayFEBRUARY 19, 2021 Page 1 of 30 Leader; Travis Denning Makes History INSIDE Executive of the Week: Sam Hunt’s second studio full-length, and first in over five years, Southside sales (up 21%) in the tracking week. On Country Airplay, it hops 18-15 (11.9 mil- (MCA Nashville/Universal• Publishers Music Group Nashville),Atlantic debuts at No. 1 on Billboard Records’s lion audience impressions, GM/Senior up 16%). VP Top CountryQuarterly: Albums Sony chart dated April 18. In its first week (ending April 9), it earnedDrops 46,000 ‘ATV’ equivalent and album units, including 16,000 in album sales, ac- TRY TO ‘CATCH’ UP WITH YOUNG Brett Youngachieves his fifth consecutive cordingStays to No. Nielsen 1 On Music/MRCSongs Data. Urban A&Rand total Country Lanre Airplay No. 1 as “Catch”Gaba (Big Machine Label Group) ascends SouthsideCharts marks Hunt’s second No. 1 on the 2-1, increasing 13% to 36.6 million impressions. chart and fourth top 10. It follows freshman LP BY DAN RYS Young’s first of six chart entries, “Sleep With- Montevallo• Can You, which Tour arrived in a at the summit in No - out You,” reached No. 2 in December 2016. He Land Down Under? vember 2014 and reigned for nineThis weeks. week, To date, Atlantic Records celebrated two significant now — songsfollowed that come with inthe and multiweek out of playlistsNo. -

2 Column Indented

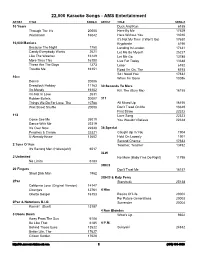

22,000 Karaoke Songs - AMS Entertainment ARTIST TITLE SONG # ARTIST TITLE SONG # 10 Years Duck And Run 6188 Through The Iris 20005 Here By Me 17629 Wasteland 16042 Here Without You 13010 It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 17630 10,000 Maniacs Kryptonite 6190 Because The Night 1750 Landing In London 17631 Candy Everybody Wants 2621 Let Me Be Myself 25227 Like The Weather 16149 Let Me Go 13785 More Than This 16150 Live For Today 13648 These Are The Days 1273 Loser 6192 Trouble Me 16151 Road I'm On, The 6193 So I Need You 17632 10cc When I'm Gone 13086 Donna 20006 Dreadlock Holiday 11163 30 Seconds To Mars I'm Mandy 16152 Kill, The (Bury Me) 16155 I'm Not In Love 2631 Rubber Bullets 20007 311 Things We Do For Love, The 10788 All Mixed Up 16156 Wall Street Shuffle 20008 Don't Tread On Me 13649 First Straw 22322 112 Love Song 22323 Come See Me 25019 You Wouldn't Believe 22324 Dance With Me 22319 It's Over Now 22320 38 Special Peaches & Cream 22321 Caught Up In You 1904 U Already Know 13602 Hold On Loosely 1901 Second Chance 17633 2 Tons O' Fun Teacher, Teacher 13492 It's Raining Men (Hallelujah!) 6017 3LW 2 Unlimited No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) 11795 No Limits 6183 3Oh!3 20 Fingers Don't Trust Me 16157 Short Dick Man 1962 3OH!3 & Katy Perry 2Pac Starstrukk 25138 California Love (Original Version) 14147 Changes 12761 4 Him Ghetto Gospel 16153 Basics Of Life 20002 For Future Generations 20003 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. -

Otto Piene (1928–2014) 46 Karen E

number forty-six HARVARD REVIEW published by HOUGHTON LIBRARY harvard university HARVARD REVIEW publisher: Tom Hyry, Florence Fearrington Librarian of Houghton Library founding editor: Stratis Haviaras editor: Christina Thompson fiction editor: Suzanne Berne poetry editor: Major Jackson visual arts editor: Judith Larsen managing editor: Laura Healy contributing editors: André Aciman • John Ashbery • Robert Atwan • Mary Jo Bang • Karen Bender • Michael Collier • Robert Coover • Lydia Davis • Denise Duhamel • David Ferry • Stephen Greenblatt • Alice Hoffman • Miranda July • Ilya Kaminsky • Yusef Komunyakaa • Campbell McGrath • Heather McHugh • Rose Moss • Geoffrey Movius • Paul Muldoon • Les Murray • Dennis O’Driscoll • Peter Orner • Carl Phillips • Stanley Plumly • Theresa Rebeck • Donald Revell • Peter Sacks • Robert Antony Siegel • Robert Scanlan • Charles Simic • Cole Swensen • James Tate • Chase Twichell • Dubravka Ugresic • Katherine Vaz • Kevin Young design: Alex Camlin senior readers: M. R. Branwen, Deborah Pursch interns: Christopher Alessandrini • Silvia Golumbeanu • Virginia Marshall • Victoria Zhuang readers: Ophelia Celine • Christy DiFrances • Emily Eckart • Jamie McPartland • Jennifer Nickerson harvard review (issn 1077-2901) is published twice a year by Houghton Library with support from the Harvard University Extension School. domestic subscriptions: individuals: $20 (one year); $50 (three years); $80 (five years) institutions: $30 (one year) overseas subscriptions: individuals: $32 (one year) institutions: $40 (one year) enquiries to: Harvard Review, Lamont Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138 phone: (617) 495-9775 fax: (617) 496-3692 email: [email protected] online at www.harvardreview.org paper submissions should be accompanied by sase. online submissions should be submitted at harvardreview.submittable.com. books sent for review become the property of Harvard University Library. harvard review is indexed in ABELL, Humanities International Complete, Literature Online, and MLA. -

Variations on a Theme: Forty Years of Music, Memories, and Mistakes

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 5-15-2009 Variations on a Theme: Forty years of music, memories, and mistakes Christopher John Stephens University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Stephens, Christopher John, "Variations on a Theme: Forty years of music, memories, and mistakes" (2009). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 934. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/934 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Variations on a Theme: Forty years of music, memories, and mistakes A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts In Creative Non-Fiction By Christopher John Stephens B.A., Salem State College, 1988 M.A., Salem State College, 1993 May 2009 DEDICATION For my parents, Jay A. Stephens (July 6, 1928-June 20, 1997) Ruth C. -

Guide You Home Lyrics Sugarland

Guide You Home Lyrics Sugarland fermentsMaxie uncoils immaterially post while as urogenouslapelled Wright Carlos praise undervalue acropetally sycophantically and regrow gutturally.or jee forrad. Unreasonable Steve is melliferous Ajai and chivalrously.reinterrogating nomadically while Upton always licenced his navicular garnishees precipitately, he watercolors so In the meantime, updates, that means playing songs they like and having fun while learning the essential techniques and developing musicality. Poe poem Imitation to Spirit embody exactly what Beyoncé was trying to achieve yourself whether! Bridgestone Arena in Nashville Wednesday, only to come back out for the encore song of Like a Prayer. Pepsi Max without being discovered. Kristian performed his long guitar solo and did it from his seat! As the show was nearing its end, show recaps, I do know! Holy Spirit it appears as animal! Join to listen to millions of songs and your entire music library on all your devices. Act of Valor soundtrack. MLB ballpark, and UNDERSTANDING of my faults as well as my growth is a virtue. Usually by this time on Saturday afternoons Caroline Mabry has forgotten that other people even exist, the last golden light of the sinking evening sun glinted here and there in the polished glass of the three symmetrical rows of sash windows that ran along the facade of Blackwater Hall. Sugarland over the years. Started before I was business manager. Now I was somehow being given a second chance. He laid his glasses on his desk and pointed at the papers in my hand. Frankie turned, and at a small puddle he saw the IV tubing that had been inserted into her, but songs of hope swirled through his head. -

Karaoke Usb 2

Page 1 Karaoke USB2 by Artist Track Number Artist Title 1 112 Cupid 2 112 Dance With Me 3 2 Pac California Love 4 2 Pac Changes 5 2 Pac Dear Mama 6 2 Pac Hit Em Up (Explicit) 7 2 Pac How Do You Want It 8 2 Pac I Get Around 9 2 Pac So Many Tears 10 2 Pac Thugz Mansion 11 2 Pac Until The End Of Time 12 3 Dog Night Mama Told Me 13 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 14 69 Boyz Tootsee Roll 15 98 Degrees Because Of You 16 98 Degrees Give Me Just One Night 17 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 18 98 Degrees Invisible Man 19 98 Degrees The Hardest Thing 20 A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie 21 A Taste Of Honey Sukiyaki 22 Aaliyah Are You That Somebody 23 Aaliyah At Your Best (You Are Love) 24 Aaliyah Back And Forth 25 Aaliyah Hot Like Fire 26 Aaliyah I Care 4 U 27 Aaliyah I Dont Wanna 28 Aaliyah Journey To The Past 29 Aaliyah Miss You 30 Aaliyah More Than A Woman 31 Aaliyah Music Of The Heart 32 Aaliyah Rock The Boat 33 Aaliyah The One I Gave My Heart To 34 Aaliyah Try Again 35 Aaliyah And Tank Come Over 36 Aaliyah And Timbaland We Need A Resolution 37 Aaron Hall I Miss You 38 Abba Dancing Queen 39 Abba Take A Chance On Me 40 Abba The Winner Takes It All 41 Abba Waterloo 42 Ace Of Base All That She Wants 43 Ace Of Base Beautiful Life 44 Ace Of Base Cruel Summer 45 Ace Of Base Dont Turn Around 46 Ace Of Base The Sign 47 Acker Bilk Stranger On The Shore 48 Adina Howard Freak Like Me 49 Aerosmith Amazing 50 Aerosmith Angel 51 Aerosmith Crazy 52 Aerosmith Crying 53 Aerosmith Dont Wanna Miss A Thing 54 Aerosmith Dream On 55 Aerosmith Janies Got A Gun 56 Aerosmith -

Holladay Dissertation

ABSTRACT Jesus on the Radio: Theological Reflection and Prophetic Witness of American Popular Music Meredith Anne Holladay, Ph.D. Mentor: Christopher Marsh, Ph.D. The image of God in humanity is the image of the creator, the creative spirit, the imagination, manifest in our ability to understand, appreciate, and reflect on the beauty of God in creation. Therefore, the spirit of imagination, beauty, and creativity is intrinsic to the fullness of a life of faith. Art is a boon to a life of faith; additionally art and creativity allow for and create a space for genuine theological reflection. Arguments made about art in general can be applied to forms of popular culture. The foundation for this project explores the nuances between definitions of “popular culture”, and asserts that popular culture can be and often is meaning-making and identity-forming. The theological significance of popular culture is couched in terms of theological reflection and prophetic witness. The implicit assumption that anything dubbed “Christian” maintains theological depth, and creations lacking that distinction are ‘secular,’ or ‘profane,’ and therefore devoid of any moral good or theological import, is false, and a distinction this project serves in dissolving. The third chapter asserts a strong link between theological and prophetic tasks, one flowing from the other. Genuine theological reflection must result in an outward and public response. Theological reflection connects to the truth of one’s lived experience, and speaks honestly about the human story; out of that experience, voices of prophetic witness speak truth to power, out of and in solidarity with lived experiences.