Introduction to a Forum on Migration in Early Medieval China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Overview of Hakka Migration History: Where Are You From?

客家 My China Roots & CBA Jamaica An overview of Hakka Migration History: Where are you from? July, 2016 www.mychinaroots.com & www.cbajamaica.com 15 © My China Roots An Overview of Hakka Migration History: Where Are You From? Table of Contents Introduction.................................................................................................................................... 3 Five Key Hakka Migration Waves............................................................................................. 3 Mapping the Waves ....................................................................................................................... 3 First Wave: 4th Century, “the Five Barbarians,” Jin Dynasty......................................................... 4 Second Wave: 10th Century, Fall of the Tang Dynasty ................................................................. 6 Third Wave: Late 12th & 13th Century, Fall Northern & Southern Song Dynasties ....................... 7 Fourth Wave: 2nd Half 17th Century, Ming-Qing Cataclysm .......................................................... 8 Fifth Wave: 19th – Early 20th Century ............................................................................................. 9 Case Study: Hakka Migration to Jamaica ............................................................................ 11 Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 11 Context for Early Migration: The Coolie Trade........................................................................... -

Chronology of Chinese History

Chronology of Chinese History I. Prehistory Neolithic Period ca. 8000-2000 BCE Xia (Hsia)? Trad. 2200-1766 BCE II. The Classical Age (Ancient China) Shang Dynasty ca. 1600-1045 BCE (Trad. 1766-1122 BCE) Zhou (Chou) Dynasty ca. 1045-256 BCE (Trad. 1122-256 BCE) Western Zhou (Chou) ca. 1045-771 BCE Eastern Zhou (Chou) 770-256 BCE Spring and Autumn Period 722-468 BCE (770-404 BCE) Warring States Period 403-221 BCE III. The Imperial Era (Imperial China) Qin (Ch’in) Dynasty 221-207 BCE Han Dynasty 202 BCE-220 CE Western (or Former) Han Dynasty 202 BCE-9 CE Xin (Hsin) Dynasty 9-23 Eastern (or Later) Han Dynasty 25-220 1st Period of Division 220-589 The Three Kingdoms 220-265 Shu 221-263 Wei 220-265 Wu 222-280 Jin (Chin) Dynasty 265-420 Western Jin (Chin) 265-317 Eastern Jin (Chin) 317-420 Southern Dynasties 420-589 Former (or Liu) Song (Sung) 420-479 Southern Qi (Ch’i) 479-502 Southern Liang 502-557 Southern Chen (Ch’en) 557-589 Northern Dynasties 317-589 Sixteen Kingdoms 317-386 NW Dynasties Former Liang 314-376, Chinese/Gansu Later Liang 386-403, Di/Gansu S. Liang 397-414, Xianbei/Gansu W. Liang 400-422, Chinese/Gansu N. Liang 398-439, Xiongnu?/Gansu North Central Dynasties Chang Han 304-347, Di/Hebei Former Zhao (Chao) 304-329, Xiongnu/Shanxi Later Zhao (Chao) 319-351, Jie/Hebei W. Qin (Ch’in) 365-431, Xianbei/Gansu & Shaanxi Former Qin (Ch’in) 349-394, Di/Shaanxi Later Qin (Ch’in) 384-417, Qiang/Shaanxi Xia (Hsia) 407-431, Xiongnu/Shaanxi Northeast Dynasties Former Yan (Yen) 333-370, Xianbei/Hebei Later Yan (Yen) 384-409, Xianbei/Hebei S. -

Tradition and Modernity in 20Th Century Chinese Poetry

Tradition and Modernity in 20th Century Chinese Poetry Rob Voigt Dan Jurafsky Center for East Asian Studies Linguistics Department Stanford University Stanford University [email protected] [email protected] Abstract Julia Lin notes that the period following the May Fourth Movement through 1937 saw “the most ex- Scholars of Chinese literature note that citing and diverse experimentation in the history of China’s tumultuous literary history in the modern Chinese poetry” (Lin, 1973). Much of this 20th century centered around the uncomfort- experimentation was concerned with the question able tensions between tradition and modernity. In this corpus study, we develop and auto- of modernity versus tradition, wherein some poets matically extract three features to show that “adapt[ed] the reality of the modern spoken lan- the classical character of Chinese poetry de- guage to what they felt was the essence of the old creased across the century. We also find that classical Chinese forms” (Haft, 1989). Taiwan poets constitute a surprising excep- The founding of the People’s Republic of China tion to the trend, demonstrating an unusually in 1949 was a second major turning point in the strong connection to classical diction in their work as late as the ’50s and ’60s. century, when “the Communists in one cataclysmic sweep [...] ruthlessly altered the course of the arts” and poetry “became totally subservient to the dic- 1 Introduction tates of the party” (Lin, 1973). With the “physi- For virtually all of Chinese history through the fall cal removal of the old cultural leadership,” many of of the Qing Dynasty, poetry was largely written in whom fled to Taiwan, this period saw a substantial Classical Chinese and accessible to a small, edu- “vacuum in literature and the arts” (McDougall and cated fraction of the population. -

Official Colours of Chinese Regimes: a Panchronic Philological Study with Historical Accounts of China

TRAMES, 2012, 16(66/61), 3, 237–285 OFFICIAL COLOURS OF CHINESE REGIMES: A PANCHRONIC PHILOLOGICAL STUDY WITH HISTORICAL ACCOUNTS OF CHINA Jingyi Gao Institute of the Estonian Language, University of Tartu, and Tallinn University Abstract. The paper reports a panchronic philological study on the official colours of Chinese regimes. The historical accounts of the Chinese regimes are introduced. The official colours are summarised with philological references of archaic texts. Remarkably, it has been suggested that the official colours of the most ancient regimes should be the three primitive colours: (1) white-yellow, (2) black-grue yellow, and (3) red-yellow, instead of the simple colours. There were inconsistent historical records on the official colours of the most ancient regimes because the composite colour categories had been split. It has solved the historical problem with the linguistic theory of composite colour categories. Besides, it is concluded how the official colours were determined: At first, the official colour might be naturally determined according to the substance of the ruling population. There might be three groups of people in the Far East. (1) The developed hunter gatherers with livestock preferred the white-yellow colour of milk. (2) The farmers preferred the red-yellow colour of sun and fire. (3) The herders preferred the black-grue-yellow colour of water bodies. Later, after the Han-Chinese consolidation, the official colour could be politically determined according to the main property of the five elements in Sino-metaphysics. The red colour has been predominate in China for many reasons. Keywords: colour symbolism, official colours, national colours, five elements, philology, Chinese history, Chinese language, etymology, basic colour terms DOI: 10.3176/tr.2012.3.03 1. -

Modernism in Practice: Shi Zhecun's Psychoanalytic Fiction Writing

Modernism in Practice: Shi Zhecun's Psychoanalytic Fiction Writing Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Zhu, Yingyue Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 26/09/2021 14:07:54 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/642043 MODERNISM IN PRACTICE: SHI ZHECUN’S PSYCHOANALYTIC FICTION WRITING by Yingyue Zhu ____________________________ Copyright © Yingyue Zhu 2020 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2020 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Master’s Committee, we certify that we have read the thesis prepared by Yingyue Zhu, titled MODERNISM IN PRACTICE: SHI ZHECUN’S PSYCHOANALYTIC FICTION WRITING and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Master’s Degree. Jun 29, 2020 _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________ Dian Li Fabio Lanza Jul 2, 2020 _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________ Fabio Lanza Jul 2, 2020 _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________ Scott Gregory Final approval and acceptance of this thesis is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the thesis to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this thesis prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the Master’s requirement. -

Shijing and Han Yuefu

SONGS THAT TOUCH OUR SOUL A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF FOLK SONGS IN TWO CHINESE CLASSICS: SHIJING AND HAN YUEFU by Yumei Wang A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Art Graduate Department of the East Asian Studies University of Toronto © Yumei Wang 2012 SONGS THAT TOUCH OUR SOUL A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF FOLK SONGS IN TWO CHINESE CLASSICS: SHIJING AND HAN YUEFU Yumei Wang Master of Art Graduate Department of the East Asian Studies University of Toronto 2012 Abstract The subject of my thesis is the comparative study of classical Chinese folk songs. Based on Jeffrey Wainwright, George Lansing Raymond, and Liu Xie’s theories, this study was conducted from four perspectives: theme, content, prosody structure and aesthetic features. The purposes of my thesis are to trace the originality of 160 folk songs in Shijing and 47 folk songs in Han yuefu , to illuminate the origin of Chinese folk songs and to demonstrate the secularism reflected in Chinese folk songs. My research makes contribution to the following four areas: it explores the relation between folk songs in Shijing and Han yuefu and compares the similarities and differences between them ; it reveals the poetic kinship between Shijing and Han yuefu; it evaluates the significance of the common people’s compositions; and it displays the unique artistic value and cultural influence of Chinese early folk songs. ii Acknowledgments I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor Professor Graham Sanders for his supervision, inspirations, and encouragements during my two years M.A study in the Department of East Asian Studies at University of Toronto. -

An Explanation of Gexing

Front. Lit. Stud. China 2010, 4(3): 442–461 DOI 10.1007/s11702-010-0107-5 RESEARCH ARTICLE XUE Tianwei, WANG Quan An Explanation of Gexing © Higher Education Press and Springer-Verlag 2010 Abstract Gexing 歌行 is a historical and robust prosodic style that flourished (not originated) in the Tang dynasty. Since ancient times, the understanding of the prosody of gexing has remained in debate, which focuses on the relationship between gexing and yuefu 乐府 (collection of ballad songs of the music bureau). The points-of-view held by all sides can be summarized as a “grand gexing” perspective (defining gexing in a broad sense) and four major “small gexing” perspectives (defining gexing in a narrow sense). The former is namely what Hu Yinglin 胡应麟 from Ming dynasty said, “gexing is a general term for seven-character ancient poems.” The first “small gexing” perspective distinguishes gexing from guti yuefu 古体乐府 (tradition yuefu); the second distinguishes it from xinti yuefu 新体乐府 (new yuefu poems with non-conventional themes); the third takes “the lyric title” as the requisite condition of gexing; and the fourth perspective adopts the criterion of “metricality” in distinguishing gexing from ancient poems. The “grand gexing” perspective is the only one that is able to reveal the core prosodic features of gexing and give specification to the intension and extension of gexing as a prosodic style. Keywords gexing, prosody, grand gexing, seven-character ancient poems Received January 25, 2010 XUE Tianwei ( ) College of Humanities, Xinjiang Normal University, Urumuqi 830054, China E-mail: [email protected] WANG Quan International School, University of International Business and Economics, Beijing 100029, China E-mail: [email protected] An Explanation of Gexing 443 The “Grand Gexing” Perspective and “Small Gexing” Perspective Gexing, namely the seven-character (both unified seven-character lines and mixed lines containing seven character ones) gexing, occupies an equal position with rhythm poems in Tang dynasty and even after that in the poetic world. -

Dissertation Section 1

Elegies for Empire The Poetics of Memory in the Late Work of Du Fu (712-770) Gregory M. Patterson Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 ! 2013 Gregory M. Patterson All rights reserved ABSTRACT Elegies for Empire: The Poetics of Memory in the Late Work of Du Fu (712-770) Gregory M. Patterson This dissertation explores highly influential constructions of the past at a key turning point in Chinese history by mapping out what I term a poetics of memory in the more than four hundred poems written by Du Fu !" (712-770) during his two-year stay in the remote town of Kuizhou (modern Fengjie County #$%). A survivor of the catastrophic An Lushan rebellion (756-763), which transformed Tang Dynasty (618-906) politics and culture, Du Fu was among the first to write in the twilight of the Chinese medieval period. His most prescient anticipation of mid-Tang concerns was his restless preoccupation with memory and its mediations, which drove his prolific output in Kuizhou. For Du Fu, memory held the promise of salvaging and creatively reimagining personal, social, and cultural identities under conditions of displacement and sweeping social change. The poetics of his late work is characterized by an acute attentiveness to the material supports—monuments, rituals, images, and texts—that enabled and structured connections to the past. The organization of the study attempts to capture the range of Du Fu’s engagement with memory’s frameworks and media. It begins by examining commemorative poems that read Kuizhou’s historical memory in local landmarks, decoding and rhetorically emulating great deeds of classical exemplars. -

The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Wai Kit Wicky Tse University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Tse, Wai Kit Wicky, "Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier" (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 589. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Abstract As a frontier region of the Qin-Han (221BCE-220CE) empire, the northwest was a new territory to the Chinese realm. Until the Later Han (25-220CE) times, some portions of the northwestern region had only been part of imperial soil for one hundred years. Its coalescence into the Chinese empire was a product of long-term expansion and conquest, which arguably defined the egionr 's military nature. Furthermore, in the harsh natural environment of the region, only tough people could survive, and unsurprisingly, the region fostered vigorous warriors. Mixed culture and multi-ethnicity featured prominently in this highly militarized frontier society, which contrasted sharply with the imperial center that promoted unified cultural values and stood in the way of a greater degree of transregional integration. As this project shows, it was the northwesterners who went through a process of political peripheralization during the Later Han times played a harbinger role of the disintegration of the empire and eventually led to the breakdown of the early imperial system in Chinese history. -

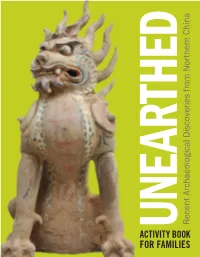

For Families Welcome to the Clark! Draw a Picture of Yourself with This Camel and Let’S Go Exploring! June 16–October 21, 2012

ACTIVITY BOOK FOR FAMILIES Welcome to the Clark! Draw a picture of yourself with this camel and let’s go exploring! JUNE 16–OCTOBER 21, 2012 ACTIVITY BOOK FOR FAMILIES elcome to the Clark and to the special exhibition Unearthed: Recent Archaeological Discoveries Wfrom Northern China. We invite you to join us on a journey to a very wonderful and very faraway place ... achusetts, to Taiyuan, China: alm n, Mass ost 8,00 stow 0 mile liam s! Wil You are here btw With 7,000 years of continuous history, China is one of the oldest civilizations in the world. The USA isn’t even 250 years old! 2 Found in the Ground This exhibition explores another type of journey: the journey from mortal life in this world to eternal life in the afterworld, a journey that ancient Chinese people hoped to take when they died. We can learn about their beliefs by looking at some of the objects that were buried with them in their tombs. Unearthed focuses on three tombs that were discovered underground in recent archaeological digs in China. These tombs give us some sense of what it was like to live in China during the times that these tombs were made. Look at the These types of tombs contained precious possessions and objects that panels on the walls represented activities, events, and things in the lives of the people who to see pictures of were buried there. These things were intended to comfort and care for the sites. their spirits in the afterlife. If you could choose three things that you could have with you forever and ever, what would they be? (Things, not people, because, according to the beliefs of the time, the people who were special to you would be there in the afterlife with you.) Ask some of your friends or 1 _______________________________ family members who came here with you today what they would pick. -

The Transition of Inner Asian Groups in the Central Plain During the Sixteen Kingdoms Period and Northern Dynasties

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2018 Remaking Chineseness: The Transition Of Inner Asian Groups In The Central Plain During The Sixteen Kingdoms Period And Northern Dynasties Fangyi Cheng University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian History Commons, and the Asian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Cheng, Fangyi, "Remaking Chineseness: The Transition Of Inner Asian Groups In The Central Plain During The Sixteen Kingdoms Period And Northern Dynasties" (2018). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2781. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2781 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2781 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Remaking Chineseness: The Transition Of Inner Asian Groups In The Central Plain During The Sixteen Kingdoms Period And Northern Dynasties Abstract This dissertation aims to examine the institutional transitions of the Inner Asian groups in the Central Plain during the Sixteen Kingdoms period and Northern Dynasties. Starting with an examination on the origin and development of Sinicization theory in the West and China, the first major chapter of this dissertation argues the Sinicization theory evolves in the intellectual history of modern times. This chapter, in one hand, offers a different explanation on the origin of the Sinicization theory in both China and the West, and their relationships. In the other hand, it incorporates Sinicization theory into the construction of the historical narrative of Chinese Nationality, and argues the theorization of Sinicization attempted by several scholars in the second half of 20th Century. The second and third major chapters build two case studies regarding the transition of the central and local institutions of the Inner Asian polities in the Central Plain, which are the succession system and the local administrative system. -

A Study of Buddha's Birthday Celebrations in Luoyang During T

《 》學報 ‧ 藝文│第十五期 外文論文 The Influence of Indian and Buddhist Elements in Medieval China: A Study of Buddha’s Birthday Celebrations In Luoyang during the Northern Wei dynasty Poh Yee WONG (aka Jue Wei SHI) Director, Nan Tien Institute Humanistic Buddhism Centre The Buddha’s birthday festival reached an unprecedented level of grandeur during the rule of Northern Wei when its capital was at Luoyang (495 to 534 CE). Buddhism1 was indigenous to neither the rulers nor the native Han Chinese. Yet, the Buddha’s birthday celebration on the eighth day of the fourth lunar month became a popular ritual in which the entire city participated. This paper studies a particular phenomenon in this public ritual, the use of carriages in image processions, tracing the heritage of these carriages back to the religion’s land of origin, India, and their literary sources. The intention of this paper is to study the reasons for such phenomenal success, in particular as they relate to the functional role of a religious festival and how the tenets of a religion can enable itself to be popular and sustainable. The Buddha’s birthday is a relevant case study because over 1,500 years later, countries such as Cambodia, Hong Kong, Macau, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, Singapore, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Taiwan, Thailand and Vietnam continue to celebrate it as their public holiday. BACKGROUND TO NORTHERN WEI AND BUDDHISM Disunity and discord accompanied warfare during the turbulent Northern 1. Dorothy Wong stated that Buddhism became a state religion under the Northern Wei in Dorothy C. Wong, Chinese Steles: Pre-Buddhist and Buddhist Use of a Symbolic Form (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2004), 46.