A Study of Buddha's Birthday Celebrations in Luoyang During T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Official Colours of Chinese Regimes: a Panchronic Philological Study with Historical Accounts of China

TRAMES, 2012, 16(66/61), 3, 237–285 OFFICIAL COLOURS OF CHINESE REGIMES: A PANCHRONIC PHILOLOGICAL STUDY WITH HISTORICAL ACCOUNTS OF CHINA Jingyi Gao Institute of the Estonian Language, University of Tartu, and Tallinn University Abstract. The paper reports a panchronic philological study on the official colours of Chinese regimes. The historical accounts of the Chinese regimes are introduced. The official colours are summarised with philological references of archaic texts. Remarkably, it has been suggested that the official colours of the most ancient regimes should be the three primitive colours: (1) white-yellow, (2) black-grue yellow, and (3) red-yellow, instead of the simple colours. There were inconsistent historical records on the official colours of the most ancient regimes because the composite colour categories had been split. It has solved the historical problem with the linguistic theory of composite colour categories. Besides, it is concluded how the official colours were determined: At first, the official colour might be naturally determined according to the substance of the ruling population. There might be three groups of people in the Far East. (1) The developed hunter gatherers with livestock preferred the white-yellow colour of milk. (2) The farmers preferred the red-yellow colour of sun and fire. (3) The herders preferred the black-grue-yellow colour of water bodies. Later, after the Han-Chinese consolidation, the official colour could be politically determined according to the main property of the five elements in Sino-metaphysics. The red colour has been predominate in China for many reasons. Keywords: colour symbolism, official colours, national colours, five elements, philology, Chinese history, Chinese language, etymology, basic colour terms DOI: 10.3176/tr.2012.3.03 1. -

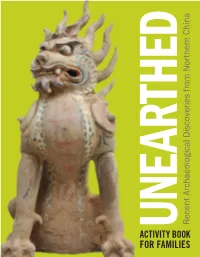

For Families Welcome to the Clark! Draw a Picture of Yourself with This Camel and Let’S Go Exploring! June 16–October 21, 2012

ACTIVITY BOOK FOR FAMILIES Welcome to the Clark! Draw a picture of yourself with this camel and let’s go exploring! JUNE 16–OCTOBER 21, 2012 ACTIVITY BOOK FOR FAMILIES elcome to the Clark and to the special exhibition Unearthed: Recent Archaeological Discoveries Wfrom Northern China. We invite you to join us on a journey to a very wonderful and very faraway place ... achusetts, to Taiyuan, China: alm n, Mass ost 8,00 stow 0 mile liam s! Wil You are here btw With 7,000 years of continuous history, China is one of the oldest civilizations in the world. The USA isn’t even 250 years old! 2 Found in the Ground This exhibition explores another type of journey: the journey from mortal life in this world to eternal life in the afterworld, a journey that ancient Chinese people hoped to take when they died. We can learn about their beliefs by looking at some of the objects that were buried with them in their tombs. Unearthed focuses on three tombs that were discovered underground in recent archaeological digs in China. These tombs give us some sense of what it was like to live in China during the times that these tombs were made. Look at the These types of tombs contained precious possessions and objects that panels on the walls represented activities, events, and things in the lives of the people who to see pictures of were buried there. These things were intended to comfort and care for the sites. their spirits in the afterlife. If you could choose three things that you could have with you forever and ever, what would they be? (Things, not people, because, according to the beliefs of the time, the people who were special to you would be there in the afterlife with you.) Ask some of your friends or 1 _______________________________ family members who came here with you today what they would pick. -

The Transition of Inner Asian Groups in the Central Plain During the Sixteen Kingdoms Period and Northern Dynasties

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2018 Remaking Chineseness: The Transition Of Inner Asian Groups In The Central Plain During The Sixteen Kingdoms Period And Northern Dynasties Fangyi Cheng University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian History Commons, and the Asian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Cheng, Fangyi, "Remaking Chineseness: The Transition Of Inner Asian Groups In The Central Plain During The Sixteen Kingdoms Period And Northern Dynasties" (2018). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2781. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2781 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2781 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Remaking Chineseness: The Transition Of Inner Asian Groups In The Central Plain During The Sixteen Kingdoms Period And Northern Dynasties Abstract This dissertation aims to examine the institutional transitions of the Inner Asian groups in the Central Plain during the Sixteen Kingdoms period and Northern Dynasties. Starting with an examination on the origin and development of Sinicization theory in the West and China, the first major chapter of this dissertation argues the Sinicization theory evolves in the intellectual history of modern times. This chapter, in one hand, offers a different explanation on the origin of the Sinicization theory in both China and the West, and their relationships. In the other hand, it incorporates Sinicization theory into the construction of the historical narrative of Chinese Nationality, and argues the theorization of Sinicization attempted by several scholars in the second half of 20th Century. The second and third major chapters build two case studies regarding the transition of the central and local institutions of the Inner Asian polities in the Central Plain, which are the succession system and the local administrative system. -

An Analysis of the Pattern and Cultural Connotations of Animal Mask Vatan in the Northern Wei Dynasty

2020 2nd International Conference on Humanities, Cultures, Arts and Design (ICHCAD 2020) An Analysis of the Pattern and Cultural Connotations of Animal Mask Vatan in the Northern Wei Dynasty Yong-Lun Li*, Wen-Bo Liu Apparel & Art Design College, Xi’an Polytechnic University, Xi’an, Shaanxi, 710048, China *Corresponding author’s email: [email protected] Keywords: Animal mask vatan, Tuoba xianbei, Buddhism, Cultural connotation Abstract: The mysterious and frightening animal mask vatan in the Northern Wei Dynasty had the function of keeping away evil spirits and holding the ability of the deterrence, which was the embodiment of the power and status of the ruling class. This paper studies and analyzes the artistic features of the animal mask vatan in the Northern Wei Dynasty from the perspective of the historical origin and modeling grain, so as to reveal the deeper cultural connotations behind. 1. Introduction The Northern Wei Dynasty (386-534) was the first ethnic minority (Tuoba Xianbei) to enter and govern the central plains for establishing a regime in history. It was also the first ethnic minority to learn the Han culture of the central plains in an all-round way. Viewing from the history, the Tuoba Xianbei’s government in the Central Plains brings fresh blood to the Han civilization, its culture combined the northern grassland culture, the western culture and the Han culture in the Central Plains, and finally created the Northern Wei culture which integrated all ethnic cultures In other words, its culture is a blending of Han culture in central plains, the northern grassland culture and western culture[1]. -

The Northern Wei Dynasty's View on Gaoche

The Frontiers of Society, Science and Technology ISSN 2616-7433 Vol. 2, Issue 8: 68-69, DOI: 10.25236/FSST.2020.020816 The Northern Wei Dynasty's View on Gaoche ShiYu Wang Inner Mongolia University, School of History and Tourism Culture, Hohhot 010070, China E-mail: 2514235625@qq. com ABSTRACT. Gaoche people is the nomadic people living in the north and northwest of China from the fourth to the sixth century A. D. According to the biography of Gaoche of Weishu, they are probably the descendants of Chidi. In the beginning, they named themselves DiLi, and the North called them Chile, They also were named Gaoche because of their tall wheels with the most spokes. This paper takes the Northern Wei Dynasty's view on Gaoche as the title, which is to sort out, summarize and sum up the relevant historical materials to draw conclusions. Wishing experts to criticize and correct my paper. KEYWORDS: Wei Dynasty's, Gaoche 1. Gaoche cavalry could be used by the court was accepted by the Northern Wei Dynasty In the second year of Emperor Taiwu of Shenjia (429), discussing whether to concentrate on attacking RouRan in the Northern Wei Dynasty, Cui Hao proposed Gaohe are famous for equestrian skill, which can make them submissive and be used by court. According to this we can know that Gaoche people are famous for their good riding skills. Gaoche cavalry was also a significant force that could not be ignored in the Northern and Southern DynastiesIn the fouth year of Shenjia (431), Mofu Kuruoyu, who is the North Chile’s general, led thousands of cavalry to meet Emperor Taiwu. -

A Freer Stela Reconsidered / Stanley K

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION WASHINGTON, D.C. A Freer Stela Reconsidered A Freer Stela Reconsidered Stanley K. Abe Occasional Papers 2002/voL 3 FREER GALLERY OF ART ARTHUR M. SACKLER GALLERY SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION WA S H I N G T N , D . C . „; '>ii'^.^"'j:'s;f tvf l-'i; —— © 2002 Smithsonian Institution Funding for this publication was provided All rights reserved by the Freer and Sackler Galleries' Publications Endowment Fund, initially Aimed at the specialist audience, the established with a grant from the Andrew Occasional Papers series represents important W. Mellon Foundation and generous new contributions and interpretations by contributions from private donors. international scholars that advance art histor- ical and conservation research. Published by Board ofthe Freer and Sackler Galleries the Freer Gallery of Art and the Anhur M. Mrs. Hart Fessenden, Chair ofthe Board Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, the Mr. Richard Danziger, Vice Chair ofthe Board series is a revival of the original Freer Gallery of Art Occasional Papers. Contributions, Dr. Siddharth K. Bhansali including monographic studies, translations, Mr. Jeffrey Cunard scientific studies of of art span the and works Mrs. Mary Patricia Wilkie Ebrahimi broad range of Asian art. Each publication Mr. George Fan its emphasis of art draws primary from works Dr. Robert Feinberg in the Freer and Sackler collections. Dr. Kurt Gitter Mrs. Margaret Haldeman Edited by Gail Spilsbury Mrs. Richard Helms Designed by Denise Arnot Sir Joseph Hotung Typeset in Garamond and Meta Mrs. Ann Kinney Printed by Weadon Printing & Mr. H. Christopher Luce Communications, Alexandria, Virginia Mrs. Jill Hornor Ma Mr. Paul Marks Cover and frontispiece: Details, stela, Ms. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced fromm icrofilm the master. UMI films the text directly firom the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be ft’om any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9218985 Spatialization in the ‘‘Shiji” Jian, Xiaobin, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1992 Copyright ©1992 by Jian, Xiaobin. All rights reserved. -

A Comparative Study of Urban Divisions Between Luoyang City in Han and Wei Dynasties and Rome City in Imperial Period

International Journal of Innovative Technologies in Social Science ISSN 2544-9338 HISTORY A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF URBAN DIVISIONS BETWEEN LUOYANG CITY IN HAN AND WEI DYNASTIES AND ROME CITY IN IMPERIAL PERIOD Jin Lipeng, PhD of department history of the Belarusian State University, Minsk, Belarus DOI: https://doi.org/10.31435/rsglobal_ijitss/30062020/7135 ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Received 27 April 2020 The author of this article briefly analyzes the layout and division of Luoyang Accepted 09 June 2020 and Roman cities during the Han and Wei Dynasties from a historical Published 30 June 2020 perspective, and explores the characteristics and traditional craftsmanship of ancient buildings in the East and the West from a comparison. KEYWORDS Luoyang City, Hanwei, Roman City, City Division. Citation: Jin Lipeng. (2020) A Comparative Study of Urban Divisions Between Luoyang City in Han and Wei Dynasties and Rome City in Imperial Period. International Journal of Innovative Technologies in Social Science. 5(26). doi: 10.31435/rsglobal_ijitss/30062020/7135 Copyright: © 2020 Jin Lipeng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms. The study of ancient Chinese and Western architecture, Luoyang City and Ancient Roman City as the representative works of ancient Chinese and Western architectural groups, is the hotspot most scholars discuss. -

Chinese Foreign Aromatics Importation

CHINESE FOREIGN AROMATICS IMPORTATION FROM THE 2ND CENTURY BCE TO THE 10TH CENTURY CE Research Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with research distinction in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University. by Shiyong Lu The Ohio State University April 2019 Project Advisor: Professor Scott Levi, Department of History 1 Introduction Trade served as a major form of communication between ancient civilizations. Goods as well as religions, art, technology and all kinds of knowledge were exchanged throughout trade routes. Chinese scholars traditionally attribute the beginning of foreign trade in China to Zhang Qian, the greatest second century Chinese diplomat who gave China access to Central Asia and the world. Trade routes on land between China and the West, later known as the Silk Road, have remained a popular topic among historians ever since. In recent years, new archaeological evidences show that merchants in Southern China started to trade with foreign countries through sea routes long before Zhang Qian’s mission, which raises scholars’ interests in Maritime Silk Road. Whether doing research on land trade or on maritime trade, few scholars concentrate on the role of imported aromatics in Chinese trade, which can be explained by several reasons. First, unlike porcelains or jewelry, aromatics are not durable. They were typically consumed by being burned or used in medicine, perfume, cooking, etc. They might have been buried in tombs, but as organic matters they are hard to preserve. Lack of physical evidence not only leads scholars to generally ignore aromatics, but also makes it difficult for those who want to do further research. -

Downloaded010006 from Brill.Com09/25/2021 09:53:09AM Via Free Access Northern and Southern Dynasties and the Course of History 89

Journal of Chinese Humanities � (�0�5) 88-��9 brill.com/joch Northern and Southern Dynasties and the Course of History Since Middle Antiquity Li Zhi’an Translated by Kathryn Henderson Abstract Two periods in Chinese history can be characterized as constituting a North/South polarization: the period commonly known as the Northern and Southern Dynasties (420AD-589AD), and the Southern Song, Jin, and Yuan Dynasties (1115AD-1368AD). Both of these periods exhibited sharp contrasts between the North and South that can be seen in their respective political and economic institutions. The North/South parity in both of these periods had a great impact on the course of Chinese history. Both before and after the much studied Tang-Song transformation, Chinese history evolved as a conjoining of previously separate North/South institutions. Once the country achieved unification under the Sui Dynasty and early part of the Tang, the trend was to carry on the Northern institutions in the form of political and economic adminis- tration. Later in the Tang Dynasty the Northern institutions and practices gave way to the increasing implementation of the Southern institutions across the country. During the Song Dynasty, the Song court initially inherited this “Southernization” trend while the minority kingdoms of Liao, Xia, Jin, and Yuan primarily inherited the Northern practices. After coexisting for a time, the Yuan Dynasty and early Ming saw the eventual dominance of the Southern institutions, while in middle to late Ming the Northern practices reasserted themselves and became the norm. An analysis of these two periods of North/South disparity will demonstrate how these differences came about and how this constant divergence-convergence influenced Chinese history. -

New Information on the Degree of “Sinicization” of the Tuyuhun

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2019 New Information on the Degree of “Sinicization” of the Tuyuhun Clan during Tang Times through Their Marriage Alliances: A Case Study Based on the Epitaphs of Two Chinese Princesses Escher, Julia Barbara Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-181630 Journal Article Published Version Originally published at: Escher, Julia Barbara (2019). New Information on the Degree of “Sinicization” of the Tuyuhun Clan during Tang Times through Their Marriage Alliances: A Case Study Based on the Epitaphs of Two Chinese Princesses. Journal of Asian History, 53(1):55-96. Offprint from: JOURNAL OF ASIAN HISTORY edited by Dorothee Schaab-Hanke and Achim Mittag 53 (2019) 1 Harrassowitz Verlag · Wiesbaden Editors / Contact: Dorothee Schaab-Hanke (Großheirath): [email protected] Achim Mittag (Tübingen): [email protected] International Advisory Board: Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Behr (Zuerich), Prof. Dr. Timothy Brook (British Columbia), Prof. Dr. Christopher Cullen (Cambridge), Prof. Dr. Roderich Ptak (Munich), Prof. Dr. Nicolas Standaert (Leuven), Prof. Dr. Barend Jan Terwiel (Hamburg) The Journal of Asian History is a refereed journal. Zugang zur elektronischen Version / Access to electronic format Diese Zeitschrift kann auch in elektronischer Form über JSTOR (www.jstor.org) bezogen werden. This journal can also be accessed electronically via JSTOR (www.jstor.org). © Otto Harrassowitz GmbH & Co. KG, Wiesbaden 2019 This journal, including all of its parts, is protected by copyright. Any use beyond the limits of copyright law without the permission of the publisher is forbidden and subject to penalty. -

From Barbarians to the Middle Kingdom: the Rise of the Title “Emperor, Heavenly Qaghan” and Its Significance

From Barbarians to the Middle Kingdom: The Rise of the Title “Emperor, Heavenly Qaghan” and Its Significance Han-je Park* INTRODUCTION The entrance of the Five Barbarians wuhu( 五胡) people into the Central Plain of China is a historical event of great significance in the East, comparable in importance to the migration of Germanic tribes into the Roman Empire. The Five Barbarians became the main actors in the establishment of an array of dynasties throughout the periods of the Sixteen Kingdoms of Five Hu, the Northern Dynasties, and eventually the cosmopolitan empires of the Sui (隋) and the Tang (唐). With the passing of time, they lost their original culture and customs, and many came to lose their ethnonym. This phenomenon is described as their sinicization (hanhua 漢化), although there is also a contrary view that the Han (漢) people in China were barbaricized (huhua 胡化) and thus widened the range of Chinese culture. But, we may ask, do the terms “sinicization” and “barbaricization” adequately convey what really happened? Aside from arguments regarding sinicization or barbaricization, what role did the Five Barbarians actually play in the history of China? Were they indeed a people without a culture, who could therefore not bring anything novel to China itself,1 or were they a civilization with a sophisticated culture of their own? *Seoul National University (Seoul, Korea) Journal of Central Eurasian Studies, Volume 3 (October 2012): 23–68 © 2012 Center for Central Eurasian Studies 24 Han-je Park The Han and Tang empires are often joined together and referred to as the “empires of the Han and the Tang,” implying that these two dynasties have a great deal in common.