The Cyclic Nature of Joni Mitchell's Court and Spark

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

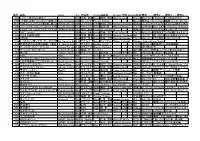

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

The Cord • Wednesday

. 1ng the 009 Polaris prize gala page19 Wednesday, September 23. 2009 thecord.ca The tie that binds Wilfrid Laurier University since 1926 Larger classes take hold at Laurier With classes now underway, the ef fects of the 2009-10 funding cuts can be seen in classrooms at Wil frid Laurier University, as several academic departments have been forced to reduce their numbers of part-time staff. As a result, class sizes have in creased and the number of class es offered each semester has decreased.' "My own view is that our admin istration is not seeing the academic side of things clearly;' said professor of sociology Garry Potter. "I don't think they properly have their eyes YUSUF KIDWAI PHOTOGRAPHY MANAGER on the ball as far as academic plan Michaellgnatieff waves to students, at a Liberal youth rally held at Wilt's on Saturday; students were bussed in from across Ontario. ninggoes:' With fewer professors teaching at Laurier, it is not possible to hold . as many different classes during the academic year and it is also more lgnatieff speaks at campus rally difficult to host multiple sections for each class. By combining sections and reduc your generation has no commit the official opposition, pinpointed ing how many courses are offered, UNDA GIVETASH ment to the political process;' said what he considers the failures of the the number of students in each class Ignatieff. current Conservative government, has increased to accommodate ev I am in it for the same The rally took place the day fol including the growing federal defi eryone enrolled at Laurier. -

Jazz Documentary

Jazz Documentary - A Great Day In Harlem - Art Kane 1958 this probably is the greatest picture of that era of musicians I think ever taken and I'm so proud of it because now it's all over the United States probably the world very something like that it was like a family reunion you know being in one spot but all these great jazz musicians at one time I mean we call big dogs I mean the Giants were there press monk I looked around and it was count face charlie means guff Smith Jessica let's be jolly nice hit oh my my can you imagine if everybody had their instruments and played [Music] back in 1958 when New York was still the jazz capital of the world you could hear important music all over town representing an extraordinary range of periods of styles this film is a story of a magic moment when dozens of the greatest jazz stars of all time gathered for an astonishing photograph whose thing started I guess in the summer of 1958 at which time I was not a photographer art Kane went from this day to become a leading player in the field of photography this was his first picture it was our director of Seventeen magazine he was one of the two or three really great young art directors in New York attack Henry wolf and arcane and one or two other people were really considered to be big bright young Kurtz Robert Benton had not yet become a celebrated Hollywood filmmaker he had only just become Esquires new art director hoping to please his jazz fan boss with an idea for an all jazz issue but his inexperience combined with pains and experience gave -

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. July 1, 2019 to Sun. July 7, 2019 Monday

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. July 1, 2019 to Sun. July 7, 2019 Monday July 1, 2019 4:00 PM ET / 1:00 PM PT 6:00 AM ET / 3:00 AM PT The Top Ten Revealed Classic Albums Guitar Rock Intros - Find out which epic Guitar Intros make our list as rock experts like Lita Ford, Black Sabbath: Paranoid - The second album by Black Sabbath, released in 1970, has long at- Steven Adler (GnR) and Vinnie Paul (Pantera) count us down! tained classic status. Paranoid not only changed the face of rock music forever, but also defined the sound and style of Heavy Metal more than any other record in rock history. 4:30 PM ET / 1:30 PM PT Cyndi Lauper 7:00 AM ET / 4:00 AM PT Punk princess Cyndi Lauper performs “Walk On By” and fun flashbacks like “Time After Time”, Rock Legends “True Colors” and “Girls Just Want To Have Fun”. Jimi Hendrix - Hailed by Rolling Stone as the greatest guitarist of all time, Jimi Hendrix was also one of the biggest cultural figures of the Sixties, a psychedelic voodoo child. Leading music 5:30 PM ET / 2:30 PM PT critics cast fresh light on the career of Jimi Hendrix. Rock Legends Blondie - The perfect punk pop band fronted by the most iconic woman in music. Always 7:30 AM ET / 4:30 AM PT creating, never following, always setting trends. After forming in the 1970s, Blondie continue to Rock & Roll Road Trip With Sammy Hagar make music and tour the world. Sunset Strip - Sammy heads to Sunset Blvd to reminisce at the Whisky A-Go-Go before visit- ing with former Mötley Crüe drummer Tommy Lee at his house. -

Girl Power: Feminine Motifs in Japanese Popular Culture David Endresak [email protected]

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU Senior Honors Theses Honors College 2006 Girl Power: Feminine Motifs in Japanese Popular Culture David Endresak [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.emich.edu/honors Recommended Citation Endresak, David, "Girl Power: Feminine Motifs in Japanese Popular Culture" (2006). Senior Honors Theses. 322. http://commons.emich.edu/honors/322 This Open Access Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact lib- [email protected]. Girl Power: Feminine Motifs in Japanese Popular Culture Degree Type Open Access Senior Honors Thesis Department Women's and Gender Studies First Advisor Dr. Gary Evans Second Advisor Dr. Kate Mehuron Third Advisor Dr. Linda Schott This open access senior honors thesis is available at DigitalCommons@EMU: http://commons.emich.edu/honors/322 GIRL POWER: FEMININE MOTIFS IN JAPANESE POPULAR CULTURE By David Endresak A Senior Thesis Submitted to the Eastern Michigan University Honors Program in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation with Honors in Women's and Gender Studies Approved at Ypsilanti, Michigan, on this date _______________________ Dr. Gary Evans___________________________ Supervising Instructor (Print Name and have signed) Dr. Kate Mehuron_________________________ Honors Advisor (Print Name and have signed) Dr. Linda Schott__________________________ Dennis Beagan__________________________ Department Head (Print Name and have signed) Department Head (Print Name and have signed) Dr. Heather L. S. Holmes___________________ Honors Director (Print Name and have signed) 1 Table of Contents Chapter 1: Printed Media.................................................................................................. -

By JENELLE RENNER Integrated Studies Final Project Essay (MAIS

AN INTERDISCIPLINARY ANALYSIS OF THE MEDIA’S PORTRAYAL OF VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN IN LEGAL CASES, SUCH AS THE JIAN GHOMESHI TRIAL, AND ITS IMPACT ON UNDER REPORTING OF ABUSE By JENELLE RENNER Integrated Studies Final Project Essay (MAIS 700) submitted to Dr. Angela Specht in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts – Integrated Studies Athabasca, Alberta April, 2016 Renner 2 AN INTERDISCIPLINARY ANALYSIS OF THE MEDIA’S PORTRAYAL OF VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN IN LEGAL CASES, SUCH AS THE JIAN GHOMESHI TRIAL, AND ITS IMPACT ON UNDER REPORTING OF ABUSE Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………………………...Page 3 Introduction………………………………………………………………………….Page 4 Research Method…………………………………………………………………….Page 5 Disciplinary Perspectives and Insights………………………………………...…….Page 6 1. Media and Communication Problems in Truth and Subjectivity in Representation: Sensational Journalism and Rape Culture A General Look at Media’s role in Normalizing and Perpetuating Violence: Humor as a Tool for Desensitization The Media’s impact on the Public’s Perception of Offenders and Victims of Sexual Assault Victim Blaming in Media Narratives Covering Sexual Assaults Problems with Coverage and Lack of Consistency in Media Support 2. Psychology Self-Blame and Internalization of Abuse Possible Reasons for “Irrational Actions” of Alleged Victims of Assault The Re-victimization from Going Public in a Trial Rape Culture and The Ghomeshi Trial The Cycle of Abuse in the Ghomeshi Trial 3. Law/Political Science Gaps in the Criminal Code How the Media Coverage Affects Potential Perpetrators Conflicts, Common Ground and Integration……………………...……………..…Page 20 Potential For Change & Future Study………………………….….……………….Page 21 Conclusion…………………………………………………….…….……………...Page 22 Work Cited………………………………………………………….…....………...Page 24 Renner 3 ABSTRACT For victims, abuse does not end after the assault; “it continues with society’s punishment, which is rarely more merciful than the violent crime itself” (Hamwe, Jasem Al 2011). -

Search Collection ' Random Item Manage Folders Manage Custom Fields Change Currency Export My Collection

Search artists, albums and more... ' Explore + Marketplace + Community + * ) + Dashboard Collection Wantlist Lists Submissions Drafts Export Settings Search Collection ' Random Item Manage Folders Manage Custom Fields Change Currency Export My Collection Collection Value:* Min $3,698.90 Med $9,882.74 Max $29,014.80 Sort Artist A-Z Folder Keepers (500) Show 250 $ % & " Remove Selected Keepers (500) ! Move Selected Artist #, Title, Label, Year, Format Min Median Max Added Rating Notes Johnny Cash - American Recordings $43.37 $61.24 $105.63 over 5 years ago ((((( #366 on R.S. top 500 List LP, Album Near Mint (NM or M-) US 1st Release American Recordings, American Recordings 9-45520-1, 1-45520 Near Mint (NM or M-) Shrink 1994 US Johnny Cash - At Folsom Prison $4.50 $29.97 $175.84 over 5 years ago ((((( #88 on R.S. top 500 List LP, Album Very Good Plus (VG+) US 1st Release Columbia CS 9639 Very Good Plus (VG+) 1968 US Johnny Cash - With His Hot And Blue Guitar $34.99 $139.97 $221.60 about 1 year ago ((((( US 1st LP, Album, Mic Very Good Plus (VG+) top & spine clear taped Sun (9), Sun (9), Sun (9) 1220, LP-1220, LP 1220 Very Good (VG) 1957 US Joni Mitchell - Blue $4.00 $36.50 $129.95 over 6 years ago ((((( #30 on R.S. top 500 List LP, Album, Pit Near Mint (NM or M-) US 1st Release Reprise Records MS 2038 Very Good Plus (VG+) 1971 US Joni Mitchell - Clouds $4.03 $15.49 $106.30 over 2 years ago ((((( US 1st LP, Album, Ter Near Mint (NM or M-) Reprise Records RS 6341 Very Good Plus (VG+) 1969 US Joni Mitchell - Court And Spark $1.99 $5.98 $19.99 -

Joni Mitchell Changes with the Times

September 21. ls-79 San Francisco'Foghorn Page 15 Greg Kihn Rocks From start to finish, the band displayed their line musicianship in all forms. Ihe rhythm section ol by Denise Sullivan "We could open with 'Sweet Larry Lynch on drums and Steve Hard driving rock and roll .lane' but we'd rather keep Wright on bass especially shone characterized the Greg Kihn building it up until thc end." stated during the encore numbers. Band's return to San Francisco Kihn flatly. "Wc do our own thing, When asked to comment on the Saturday night at thc Old Waldorf. regardless." new wave movement, Kihn's Though thc show kicked-off on a Kihn was relatively happy with immediate response was. "I like the laid-back note. Kihn and his band the night's first performance. From Pants," as he sat comfortably in managed to get the audience the onset the band rocked tightly. skintight black slacks. "I like jumping by thc final encores. "We weren't out of tune or modern girls and the modern During an informal backstage anything," smiled Kihn. world," he joked. interview between sets. Mr. Kihn The first set featured such well- Kihn is a firm supporter of new gave some of his views on rock and known numbers as "Secret bands and encourages his fans to revealed some of his thoughts on Meetings" and "Cold Hard Cash" support other local club acts like returning to thc Bay Area. from the "Next of Kihn" LP, as they backed himself in the early "We toured all thc big cities, but well as his covers of "Rendezvous days. -

Joni Mitchell," 1966-74

"All Pink and Clean and Full of Wonder?" Gendering "Joni Mitchell," 1966-74 Stuart Henderson Just before our love got lost you said: "I am as constant as a northern star." And I said: "Constantly in the darkness - Where 5 that at? Ifyou want me I'll be in the bar. " - "A Case of You," 1971 Joni Mitchell has always been difficult to categorize. A folksinger, a poet, a wife, a Canadian, a mother, a party girl, a rock star, a hermit, a jazz singer, a hippie, a painter: any or all of these descriptions could apply at any given time. Moreover, her musicianship, at once reminiscent of jazz, folk, blues, rock 'n' roll, even torch songs, has never lent itself to easy categorization. Through each successive stage of her career, her songwriting has grown ever more sincere and ever less predictable; she has, at every turn, re-figured her public persona, belied expectations, confounded those fans and critics who thought they knew who she was. And it has always been precisely here, between observers' expec- tations and her performance, that we find contested terrain. At stake in the late 1960s and early 1970s was the central concern for both the artist and her audience that "Joni Mitchell" was a stable identity which could be categorized, recognized, and understood. What came across as insta- bility to her fans and observers was born of Mitchell's view that the honest reflection of growth and transformation is the basic necessity of artistic expres- sion. As she explained in 1979: You have two options. -

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: an Analysis Into Graphic Design's

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres by Vivian Le A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems (Honors Scholar) Presented May 29, 2020 Commencement June 2020 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Vivian Le for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems presented on May 29, 2020. Title: Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres. Abstract approved:_____________________________________________________ Ryann Reynolds-McIlnay The rise of digital streaming has largely impacted the way the average listener consumes music. Consequentially, while the role of album art has evolved to meet the changes in music technology, it is hard to measure the effect of digital streaming on modern album art. This research seeks to determine whether or not graphic design still plays a role in marketing information about the music, such as its genre, to the consumer. It does so through two studies: 1. A computer visual analysis that measures color dominance of an image, and 2. A mixed-design lab experiment with volunteer participants who attempt to assess the genre of a given album. Findings from the first study show that color scheme models created from album samples cannot be used to predict the genre of an album. Further findings from the second theory show that consumers pay a significant amount of attention to album covers, enough to be able to correctly assess the genre of an album most of the time. -

Blankg5 Copy 7/1/11 3:56 PM Page 208 5Gerry:Blankg5 Copy 7/1/11 3:56 PM Page 209

5gerry:blankG5 copy 7/1/11 3:56 PM Page 208 5gerry:blankG5 copy 7/1/11 3:56 PM Page 209 TOM GERRY “I Sing My Sorrow and I Paint My Joy”: Joni Mitchell’s Songs and Images ONI MITCHELL is best known as a musician. She is a popular music superstar, and has been since the early 1970s. Surprisingly, considering Mitchell’s Jstatus in the music world, she has often said that for her, painting is primary, music and writing secondary. Regarding Mingus, her 1979 jazz album, she commented that with it she “was trying to become the Jackson Pollock of music.” In a 1998 interview Mitchell reflected, “I think of myself as a painter who writes music.”1 In our era, when many critics and philosophers view interarts relationships with suspicion, it is remarkable that Mitchell persists so vigorously in creating work that involves multiple arts. To consider Mitchell’s art as the productions of a multi-talented person does not get us far with the works themselves, since this approach immediately invokes the abstractions and speculations of psychology. On the other hand, postmodernism has taught us that there is no absolute, tran- scendent meaning available as content for various forms. In the face of such strong objections to coalescing arts, Mitchell insists through her works that her art is intrinsically multidisciplinary and needs to be understood as such. Interarts relationships have been studied at least since Aristotle decreed that the lexis, the words, takes precedence over the opsis, the spectacle, of drama. Although recognized as being distinct, the arts have also commonly been discussed as though they are analogous. -

番号 曲名 Name インデックス 作曲者 Composer 編曲者 Arranger作詞

番号 曲名 Name インデックス作曲者 Composer編曲者 Arranger作詞 Words出版社 備考 備考2 備考3 備考4 595 1 2 3 ~恋がはじまる~ 123Koigahajimaru水野 良樹 Yoshiki鄕間 幹男 Mizuno Mikio Gouma ウィンズスコアWSJ-13-020「カルピスウォーター」CMソングいきものがかり 1030 17世紀の古いハンガリー舞曲(クラリネット4重奏)Early Hungarian 17thDances フェレンク・ファルカシュcentury from EarlytheFerenc 17th Hungarian century Farkas Dances from the Musica 取次店:HalBudapest/ミュージカ・ブダペスト Leonard/ハル・レナード編成:E♭Cl./B♭Cl.×2/B.Cl HL50510565 1181 24のプレリュードより第4番、第17番24Preludes Op.28-4,1724Preludesフレデリック・フランソワ・ショパン Op.28-4,17Frédéric福田 洋介 François YousukeChopin Fukuda 音楽之友社バンドジャーナル2019年2月スコアは4番と17番分けてあります 840 スリー・ラテン・ダンス(サックス4重奏)3 Latin Dances 3 Latinパトリック・ヒケティック Dances Patric 尾形Hiketick 誠 Makoto Ogata ブレーンECW-0010Sax SATB1.Charanga di Xiomara Reyes 2.Merengue Sempre di Aychem sunal 3.Dansa Lationo di Maria del Real 997 3☆3ダンス ソロトライアングルと吹奏楽のための 3☆3Dance福島 弘和 Hirokazu Fukushima 音楽之友社バンドジャーナル2017年6月号サンサンダンス(日本語) スリースリーダンス(英語) トレトレダンス(イタリア語) トゥワトゥワダンス(フランス語) 973 360°(miwa) 360domiwa、NAOKI-Tmiwa、NAOKI-T西條 太貴 Taiki Saijyo ウィンズスコアWSJ-15-012劇場版アニメ「映画ドラえもん のび太の宇宙英雄記(スペースヒーローズ)」主題歌 856 365日の紙飛行機 365NichinoKamihikouki角野 寿和 / 青葉 紘季Toshikazu本澤なおゆき Kadono / HirokiNaoyuki Honzawa Aoba M8 QH1557 歌:AKB48 NHK連続テレビ小説『あさが来た』主題歌 685 3月9日 3Gatu9ka藤巻 亮太 Ryouta原田 大雪 Fujimaki Hiroyuki Harada ウィンズスコアWSL-07-0052005年秋に放送されたフジテレビ系ドラマ「1リットルの涙」の挿入歌レミオロメン歌 1164 6つのカノン風ソナタ オーボエ2重奏Six Canonic Sonatas6 Canonicゲオルク・フィリップ・テレマン SonatasGeorg ウィリアム・シュミットPhilipp TELEMANNWilliam Schmidt Western International Music 470 吹奏楽のための第2組曲 1楽章 行進曲Ⅰ.March from Ⅰ.March2nd Suiteグスタフ・ホルスト infrom F for 2ndGustav Military Suite Holst