Gerunds and Gerundives Chapter 39 Covers the Following

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Does English Have a Genitive Case? [email protected]

2. Amy Rose Deal – University of Massachusetts, Amherst Does English have a genitive case? [email protected] In written English, possessive pronouns appear without ’s in the same environments where non-pronominal DPs require ’s. (1) a. your/*you’s/*your’s book b. Moore’s/*Moore book What explains this complementarity? Various analyses suggest themselves. A. Possessive pronouns are contractions of a pronoun and ’s. (Hudson 2003: 603) B. Possessive pronouns are inflected genitives (Huddleston and Pullum 2002); a morphological deletion rule removes clitic ’s after a genitive pronoun. Analysis A consists of a single rule of a familiar type: Morphological Merger (Halle and Marantz 1993), familiar from forms like wanna and won’t. (His and its contract especially nicely.) No special lexical/vocabulary items need be postulated. Analysis B, on the other hand, requires a set of vocabulary items to spell out genitive case, as well as a rule to delete the ’s clitic following such forms, assuming ’s is a DP-level head distinct from the inflecting noun. These two accounts make divergent predictions for dialects with complex pronominals such as you all or you guys (and us/them all, depending on the speaker). Since Merger operates under adjacency, Analysis A predicts that intervention by all or guys should bleed the formation of your: only you all’s and you guys’ are predicted. There do seem to be dialects with this property, as witnessed by the American Heritage Dictionary (4th edition, entry for you-all). Call these English 1. Here, we may claim that pronouns inflect for only two cases, and Merger operations account for the rest. -

The Term Declension, the Three Basic Qualities of Latin Nouns, That

Chapter 2: First Declension Chapter 2 covers the following: the term declension, the three basic qualities of Latin nouns, that is, case, number and gender, basic sentence structure, subject, verb, direct object and so on, the six cases of Latin nouns and the uses of those cases, the formation of the different cases in Latin, and the way adjectives agree with nouns. At the end of this lesson we’ll review the vocabulary you should memorize in this chapter. Declension. As with conjugation, the term declension has two meanings in Latin. It means, first, the process of joining a case ending onto a noun base. Second, it is a term used to refer to one of the five categories of nouns distinguished by the sound ending the noun base: /a/, /ŏ/ or /ŭ/, a consonant or /ĭ/, /ū/, /ē/. First, let’s look at the three basic characteristics of every Latin noun: case, number and gender. All Latin nouns and adjectives have these three grammatical qualities. First, case: how the noun functions in a sentence, that is, is it the subject, the direct object, the object of a preposition or any of many other uses? Second, number: singular or plural. And third, gender: masculine, feminine or neuter. Every noun in Latin will have one case, one number and one gender, and only one of each of these qualities. In other words, a noun in a sentence cannot be both singular and plural, or masculine and feminine. Whenever asked ─ and I will ask ─ you should be able to give the correct answer for all three qualities. -

Introduction to Gothic

Introduction to Gothic By David Salo Organized to PDF by CommanderK Table of Contents 3..........................................................................................................INTRODUCTION 4...........................................................................................................I. Masculine 4...........................................................................................................II. Feminine 4..............................................................................................................III. Neuter 7........................................................................................................GOTHIC SOUNDS: 7............................................................................................................Consonants 8..................................................................................................................Vowels 9....................................................................................................................LESSON 1 9.................................................................................................Verbs: Strong verbs 9..........................................................................................................Present Stem 12.................................................................................................................Nouns 14...................................................................................................................LESSON 2 14...........................................................................................Strong -

A Study of Three Variants of Gerund Construction from the Contrastive Perspective of Social and Natural Academic Abstracts on Construction Grammar Theory1

2020 年 6 月 中国应用语言学(英文) Jun. 2020 第 43 卷 第 2 期 Chinese Journal of Applied Linguistics Vol. 43 No. 2 A Study of Three Variants of Gerund Construction from the Contrastive Perspective of Social and Natural Academic Abstracts on Construction Grammar Theory1 Yan J IN & Mingtuo YANG Northwest Normal University Abstract English gerund construction is a system composed of 3 variants, including “Gerund + ø”, “Gerund + of + NP”, and “Gerund + NP”. The noun and verb attributes of the 3 variants are recursive, and in theory their frequencies vary regularly in different styles. An abstract is placed before the beginning of an academic papers, which has the basic characteristics of conciseness and generalization, and has special requirements for the use of gerunds. The purpose of this study was to empirically explore the system of gerund construction in abstracts of natural science and social science papers, and to specifically explore the inherent characteristics of noun and verb properties of the 3 variants. For this purpose, two corpora were constructed, one is about abstracts of natural science papers, and the other is about abstracts of social science papers. Finally, the results of chi-square test showed that there was no significant difference in the frequencies of the 3 variants in the abstracts of natural science and social science papers, and the two corpora can be studied as a whole. In the combined corpus, there were significant differences in the frequencies of the 3 gerund variants. The frequencies of these 3 variants and their gerund properties showed a recursive change. Keywords: gerund construction, gerund variants, Construction Grammar, nominalization, gerund system 1 The study was supported by the Humanities and Social Sciences Research Planning Fund of Ministry of Education for Western and Frontier Areas (14XJA740001). -

Verbals: Participle Or Gerund? | Verbals Worksheets

Name: ___________________________Key VErbals: Participle or Gerund? A participle is a verb form that functions as an adjective in a sentence. A gerund is a verb form that functions as a noun in a sentence. Below are sentences using either a participle or a gerund. Read each sentence carefully. Write which verbal form appears in the sentence in the blank. 1. The jumping frog landed in her lap. _______________________________________________________________________________ 2. Lucinda had a calling to help other people. _______________________________________________________________________________ 3. The mother barely caught the crawling baby before he went into the street. _______________________________________________________________________________ 4. The house was filled with a haunting spector. _______________________________________________________________________________ 5. Running in the halls is strictly forbidden. _______________________________________________________________________________ 6. They won the award for caring for sick animals. _______________________________________________________________________________ 7. Paul bought new climbing gear. _______________________________________________________________________________ 8. Escaping was the only thought he had. _______________________________________________________________________________ Copyright © 2014 K12reader.com. All Rights Reserved. Free for educational use at home or in classrooms. www.k12reader.com Name: ___________________________Key VErbals: Participle -

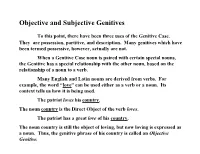

Objective and Subjective Genitives

Objective and Subjective Genitives To this point, there have been three uses of the Genitive Case. They are possession, partitive, and description. Many genitives which have been termed possessive, however, actually are not. When a Genitive Case noun is paired with certain special nouns, the Genitive has a special relationship with the other noun, based on the relationship of a noun to a verb. Many English and Latin nouns are derived from verbs. For example, the word “love” can be used either as a verb or a noun. Its context tells us how it is being used. The patriot loves his country. The noun country is the Direct Object of the verb loves. The patriot has a great love of his country. The noun country is still the object of loving, but now loving is expressed as a noun. Thus, the genitive phrase of his country is called an Objective Genitive. You have actually seen a number of Objective Genitives. Another common example is Rex causam itineris docuit. The king explained the cause of the journey (the thing that caused the journey). Because “cause” can be either a noun or a verb, when it is used as a noun its Direct Object must be expressed in the Genitive Case. A number of Latin adjectives also govern Objective Genitives. For example, Vir miser cupidus pecuniae est. A miser is desirous of money. Some special nouns and adjectives in Latin take Objective Genitives which are more difficult to see and to translate. The adjective peritus, -a, - um, meaning “skilled” or “experienced,” is one of these: Nautae sunt periti navium. -

Genitive Case

GENITIVE CASE The Genitive is the third and last case existing in both English and Latin. In English, all pronouns have a genitive case that shows possession: "his", "her", "my", "their", "whose", etc. These answer the question "Belonging to whom or what?" Regular nouns in English also have a genitive form: in the singular, the ending "'s" is added; in the plural, s'. Consider the following examples: Their father is here. The man's father is here. The boys' father is here. In Latin, the Genitive case may also show possession. However, it may be used for some other things as well, as you will see later on. It's ending of course varies depending on the original ending of the noun: for a-nouns, the singular is -ae and the plural is -ārum; for both us- and um-nouns, the singular is -ī and the plural is - ōrum. Consider the following chart: Nominative, Accusative, and Genitive Cases a-nouns us-nouns um-nouns sg. pl. sg. pl. sg. pl. Nominative a ae us ī um a Accusative Genitive ae ārum ī ōrum ī ōrum A genitive is normally paired with another noun in the sentence which it modifies. In English, it is always placed immediately before the noun it modifies: for example, "my soup", "the boy's shirt", etc. But in Latin, a genitive may be placed either before or after the noun it modifies: for example, feminae panes, panes feminae. In fact, a genitive may occasionally even be separated by another word: panes sunt feminae. Also, keep in mind that the grammatical possession that the genitive case signifies is a fairly broad and vague connection. -

TRADITIONAL GRAMMAR REVIEW I. Parts of Speech Traditional

Traditional Grammar Review Page 1 of 15 TRADITIONAL GRAMMAR REVIEW I. Parts of Speech Traditional grammar recognizes eight parts of speech: Part of Definition Example Speech noun A noun is the name of a person, place, or thing. John bought the book. verb A verb is a word which expresses action or state of being. Ralph hit the ball hard. Janice is pretty. adjective An adjective describes or modifies a noun. The big, red barn burned down yesterday. adverb An adverb describes or modifies a verb, adjective, or He quickly left the another adverb. room. She fell down hard. pronoun A pronoun takes the place of a noun. She picked someone up today conjunction A conjunction connects words or groups of words. Bob and Jerry are going. Either Sam or I will win. preposition A preposition is a word that introduces a phrase showing a The dog with the relation between the noun or pronoun in the phrase and shaggy coat some other word in the sentence. He went past the gate. He gave the book to her. interjection An interjection is a word that expresses strong feeling. Wow! Gee! Whew! (and other four letter words.) Traditional Grammar Review Page 2 of 15 II. Phrases A phrase is a group of related words that does not contain a subject and a verb in combination. Generally, a phrase is used in the sentence as a single part of speech. In this section we will be concerned with prepositional phrases, gerund phrases, participial phrases, and infinitive phrases. Prepositional Phrases The preposition is a single (usually small) word or a cluster of words that show relationship between the object of the preposition and some other word in the sentence. -

1St Rule: FANBOYS and Compound Sentences FANBOYS Is a Mnemonic Device, Which Stands for the Coordinating Conjunctions: For, And, Nor, But, Or, Yet, and So

1st Rule: FANBOYS and Compound Sentences FANBOYS is a mnemonic device, which stands for the coordinating conjunctions: For, And, Nor, But, Or, Yet, and So. These words, when used to connect two independent clauses (two complete thoughts), must be preceded by a comma. A sentence is a complete thought, consisting of a Subject and a Verb. Conjunctions should not be confused with conjunctive adverbs, such as However, Therefore, and Moreover or with conjunctions, such as Because. 2nd Rule: Introductory Bits When using an introductory word, phrase, or clause to begin a sentence, it is important to place a comma between the introduction and the main sentence. The introduction is not a complete thought on its own; it simply introduces the main clause. This lets the reader know that the “meat” of the sentence is what follows the comma. You should be able to remove the part which comes before the comma and still have a complete thought. Examples: Generally, John is opposed to overt acts of affection. However, Lucy inspires him to be kind. If the hamster is launched fifty feet, there is too much pressure in the cannon. Although the previous sentence has little to do with John and Lucy, it is a good example of how to use commas with introductory clauses. 3rd Rule: Separating Items in a Series Commas belong between each item in a list. However, in a series of three items, the comma between the second and third item and the conjunction (generally and or or) is optional, whereas in a list of four items, the comma is necessary. -

Conjunction Junction WHAT’S THEIR FUNCTION? What Are Conjunctions, Anyway?

Conjunction Junction WHAT’S THEIR FUNCTION? What are conjunctions, anyway? A conjunction is a word used to connect clauses or sentences or to coordinate words in the same clause. What kinds of conjunctions are there? • Coordinating conjunctions (=) • FANBOYS • Correlating Conjunctions • Both…and, either…or, neither…nor, whether…or, not only…but also • Subordinating Conjunctions (< ) • After, although, as, because, before, how, if, since, than, that, though, unless, until, what (whatever), when (whenever), where (wherever), whereas, whether, which (whichever), while, who (whom, whomever), whose • Conjunctive Adverb () • Accordingly, however, nonetheless, also, indeed, otherwise, besides, instead, similarly, consequently, likewise, still, conversely, meanwhile, subsequently, finally, moreover, then, furthermore, nevertheless, therefore, hence, next, thus Coordinating Conjunctions • Coordinating Conjunctions are used to connect two complete sentences(independent clauses) and coordinating words and phrases. • All coordinating conjunctions MUST be preceded by a comma if connecting two independent clauses. Coordinating Conjunctions at Work • Miss Smidgin was courteous but cool. (coordinating adjectives) • The next five minutes will determine whether we win or lose. (coordinating verbs) • This chimp is crazy about peanuts but also about strawberries. (coordinating prepositional phrases) • He once lived in mansions, yet now he is living in an empty box. (coordinating independent clauses) • You probably won’t have any trouble spotting him, for he weighs almost three hundred pounds. • She didn’t offer help, nor did she offer any excuse for her laziness. • I wanted to live closer to Nature, so I built myself a cabin in the swamps of Louisiana. Correlating Conjunctions Correlating Conjunctions connect two equal phrases. Correlating Conjunctions at Work • In the fall, Phillip will either start classes at the community college or join the navy. -

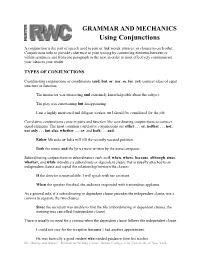

Using-Conjunctions.Pdf

GRAMMAR AND MECHANICS Using Conjunctions A conjunction is the part of speech used to join or link words, phrases, or clauses to each other. Conjunctions help to provide coherence to your writing by connecting elements between or within sentences and from one paragraph to the next in order to most effectively communicate your ideas to your reader. TYPES OF CONJUNCTIONS Coordinating conjunctions or coordinators (and, but, or, nor, so, for, yet) connect ideas of equal structure or function. The instructor was interesting and extremely knowledgeable about the subject. The play was entertaining but disappointing. I am a highly motivated and diligent worker, so I should be considered for the job. Correlative conjunctions come in pairs and function like coordinating conjunctions to connect equal elements. The most common correlative conjunctions are either . or, neither . nor, not only . but also, whether . or, and both . and. Either Miranda or Julia will fill the recently vacated position. Both the music and the lyrics were written by the same composer. Subordinating conjunctions or subordinators such as if, when, where, because, although, since, whether, and while introduce a subordinate or dependent clause that is usually attached to an independent clause and signal the relationship between the clauses. If the director is unavailable, I will speak with her assistant. When the speaker finished, the audience responded with tremendous applause. As a general rule, if a subordinating or dependent clause precedes the independent clause, use a comma to separate the two clauses. Since the secretary was unable to find the file (subordinating or dependent clause), the meeting was cancelled (independent clause). -

The Formation of the Fifth Declension; Uses of the Ablative Case; and at the End of the Lesson We'll Review the Vocabulary Which You Should Memorize in This Chapter

Chapter 22: Fifth Declension. Chapter 22 covers the following: the formation of the fifth declension; uses of the ablative case; and at the end of the lesson we'll review the vocabulary which you should memorize in this chapter. There is one important rule to remember in this chapter: fifth declension represents e-stem nouns which are for the most part feminine in gender. Fifth Declension. Hooray, hooray! Latin only has five declensions, so this is the last declension we'll study. Once you've mastered fifth declension, you've learned everything you need to know about Latin nouns in this class. Fifth declension consists of nouns characterized by -ē. This declension is a unique concoction which the Romans brewed up at one point in their history and which did not survive long. As Latin after classical antiquity began evolving into the various Romance languages, this e-stem category of nouns was conflated into other declensions and disappeared as a separate grammatical category. Here are the endings for fifth-declension nouns. Let's recite them together: -es, -ei, -ei, -em, -e; -es, -erum, -ebus, -es, -ebus. Note the dominance of -e- (often -ē-) which is, without doubt, the most significant feature of this declension, though the -ē- produces no mandatory long marks, meaning no forms are distinguished by macrons in this declension. A close look at the endings shows why it was easy for the post-classical Romans to subsume fifth declension into third, for instance. Fifth and third look a lot like each other. In fact, the majority of fifth-declension endings look like a long ē-stem with third-declension endings appended on to it.