Religion and the Discourse of Human Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Martha L. Minow

Martha L. Minow 1525 Massachusetts Avenue Griswold 407, Harvard Law School Cambridge, MA 02138 (617) 495-4276 [email protected] Current Academic Appointments: 300th Anniversary University Professor, Harvard University Harvard University Distinguished Service Professor Faculty, Harvard Graduate School of Education Faculty Associate, Carr Center for Human Rights, Harvard Kennedy School of Government Current Activities: Advantage Testing Foundation, Vice-Chair and Trustee American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Access to Justice Project American Bar Association Center for Innovation, Advisory Council American Law Institute, Member Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society, Harvard University, Director Campaign Legal Center, Board of Trustees Carnegie Corporation, Board of Trustees Committee to Visit the Harvard Business School, Harvard University Board of Overseers Facing History and Ourselves, Board of Scholars Harvard Data Science Review, Associate Editor Initiative on Harvard and the Legacy of Slavery Law, Violence, and Meaning Series, Univ. of Michigan Press, Co-Editor MacArthur Foundation, Director MIT Media Lab, Advisory Council MIT Schwarzman College of Computing, Co-Chair, External Advisory Council National Academy of Sciences' Committee on Science, Technology, and Law Profiles in Courage Award Selection Committee, JFK Library, Chair Russell Sage Foundation, Trustee Skadden Fellowship Foundation, Selection Trustee Susan Crown Exchange Foundation, Trustee WGBH Board of Trustees, Trustee Education: Yale Law School, J.D. 1979 Articles and Book Review Editor, Yale Law Journal, 1978-1979 Editor, Yale Law Journal, 1977-1978 Harvard Graduate School of Education, Ed.M. 1976 University of Michigan, A.B. 1975 Phi Beta Kappa, Magna Cum Laude James B. Angell Scholar, Branstrom Prize New Trier East High School, Winnetka, Illinois, 1968-1972 Honors and Fellowships: Leo Baeck Medal, Nov. -

Marking 200 Years of Legal Education: Traditions of Change, Reasoned Debate, and Finding Differences and Commonalities

MARKING 200 YEARS OF LEGAL EDUCATION: TRADITIONS OF CHANGE, REASONED DEBATE, AND FINDING DIFFERENCES AND COMMONALITIES Martha Minow∗ What is the significance of legal education? “Plato tells us that, of all kinds of knowledge, the knowledge of good laws may do most for the learner. A deep study of the science of law, he adds, may do more than all other writing to give soundness to our judgment and stability to the state.”1 So explained Dean Roscoe Pound of Harvard Law School in 1923,2 and his words resonate nearly a century later. But missing are three other possibilities regarding the value of legal education: To assess, critique, and improve laws and legal institutions; To train those who pursue careers based on legal training, which may mean work as lawyers and judges; leaders of businesses, civic institutions, and political bodies; legal academics; or entre- preneurs, writers, and social critics; and To advance the practice in and study of reasoned arguments used to express and resolve disputes, to identify commonalities and dif- ferences, to build institutions of governance within and between communities, and to model alternatives to violence in the inevi- table differences that people, groups, and nations see and feel with one another. The bicentennial of Harvard Law School prompts this brief explo- ration of the past, present, and future of legal education and scholarship, with what I hope readers will not begrudge is a special focus on one particular law school in Cambridge, Massachusetts. ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– ∗ Carter Professor of General Jurisprudence; until July 1, 2017, Morgan and Helen Chu Dean and Professor, Harvard Law School. -

Jewish Law and Current Legal Problems

JEWISH LAW AND CURRENT LEGAL PROBLEMS JEWISH LAW AND CURRENT LEGAL PROBLEMS EDITED BY NAHUM RAKOVER The Library of Jewish Law The Library of Jewish Law Ministry of Justice The Jewish Legal Heritage Society Foundation for the Advancement of Jewish Law PROCEEDINGS of the First International Seminar on The Sources Of Contemporary Law: The Bible and Talmud and Their Contribution to Modern Legal Systems Jerusalem. August 1983 © The Library of Jewish Law The Jewish Lcg<1l Heritage Society P.O.Box 7483 Jerusalem 91074 1984 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE 9 GREETINGS OF THE MINISTER OF JUSTICE, Moshe Nissim II LEGAL THEORY Haim H. Cohn THE LESSON OF JEWISH LAW FOR 15 LEGAL CHANGE Meyer S. Feldblum THE EMERGENCE OF THE HALAKHIC 29 LEGAL SYSTEM Classical and Modern Perceptions Norman Solomon EXTENSIVE AND RESTRICTIVE 37 INTERPRETATION LAW IN CHANGING SOCIETIES Yedidya Cohen THE KIBBUTZ AS A LEGAL ENTITY 55 Reuben Ahroni THE LEVIRATE AND HUMAN RIGHTS 67 JUDICIAL PROCESS Haim Shine COMPROMISE 77 5 POLITICAL THEORY Emanuel Rackman THE CHURCH FATHERS AND HEBREW 85 POLITICAL THOUGHT LAW AND RELIGION John Wade THE INFLUENCE OF RELIGION UPON LAW 97 Bernard J. Meis/in THE TEN COMMANDMENTS IN AMERICAN 109 LAW PENAL LAW Ya'akov Bazak MAIMONIDES' VIEWS ON CRIME AND 121 PUNISHMENT Yehuda Gershuni EXTRADITION 127 Nahum Rakover COERCION IN CONJUGAL RELATIONS 137 SELF-INCRIMINATION Isaac Braz THE PRIVILEGE AGAINST SELF 161 INCRIMINATION IN ANGLO-AMERICAN LAW The Influence of Jewish Law Arnold Enker SELF-INCRIMINATION 169 Malvina Halberstam THE RATIONALE FOR EXCLUDING 177 INCRIMINATING STATEMENTS U.S. Law Compared to Ancient Jewish Law Stanley Levin DUE PROCESS IN RABBINICAL AND 191 ISRAELI LAW Abuse and Subversion 6 MEDICAL ETHICS David A. -

German Law in Israeli Courts

German Law in Israeli Courts Nili Cohen Introduction: Alexander the Great as Comparatist Comparisons constitute a focal point for the perception of cultures, na- tions, and ourselves. The crux of comparison is the marking of dis- tinctions and similarities. Paradoxically, the scrutiny of differences can yield unifying factors and the affirmation of gaps can build bridges. Law, which is a normative system built on tradition and culture, has long been the object of comparative inquiry. The comparative study of law can be traced to antiquity. The Tal- mud tells of a meeting between Alexander the Great and the king of an imaginary state called Katsia.1 Alexander is interested in the gover- nance of that land and is invited by its monarch to attend a trial dealing with the purchase of a residence. The dispute, which concerns some treasure found in the house, takes an unexpected turn. Both the vendor and the purchaser claim that the treasure-trove belongs to the other: the purchaser argues that as he bought only the house, the treasure ought to be restored to the vendor, while the vendor argues that as he sold the house with its contents, the treasure should stay with the purchaser. The king of Katsia rules that the vendor’s son and the purchaser’s daughter should marry, with the treasure then becoming part of their common property. Alexander is shocked. In his kingdom, both claimants would have been beheaded, and the treasure would have been awarded to the king. Now it is the turn of the king of Katsia to be shocked. -

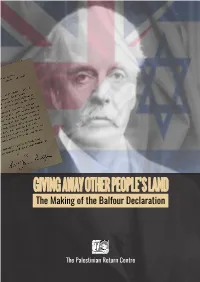

The Making of the Balfour Declaration

The Making of the Balfour Declaration The Palestinian Return Centre i The Palestinian Return Centre is an independent consultancy focusing on the historical, political and legal aspects of the Palestinian Refugees. The organization offers expert advice to various actors and agencies on the question of Palestinian Refugees within the context of the Nakba - the catastrophe following the forced displacement of Palestinians in 1948 - and serves as an information repository on other related aspects of the Palestine question and the Arab-Israeli conflict. It specializes in the research, analysis, and monitor of issues pertaining to the dispersed Palestinians and their internationally recognized legal right to return. Giving Away Other People’s Land: The Making of the Balfour Declaration Editors: Sameh Habeeb and Pietro Stefanini Research: Hannah Bowler Design and Layout: Omar Kachouch All rights reserved ISBN 978 1 901924 07 7 Copyright © Palestinian Return Centre 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publishers or author, except in the case of a reviewer, who may quote brief passages embodied in critical articles or in a review. مركز العودة الفلسطيني PALESTINIAN RETURN CENTRE 100H Crown House North Circular Road, London NW10 7PN United Kingdom t: 0044 (0) 2084530919 f: 0044 (0) 2084530994 e: [email protected],uk www.prc.org.uk ii Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................3 -

CCAR Journal the Reform Jewish Quarterly

CCAR Journal The Reform Jewish Quarterly Halachah and Reform Judaism Contents FROM THE EDITOR At the Gates — ohrgJc: The Redemption of Halachah . 1 A. Brian Stoller, Guest Editor ARTICLES HALACHIC THEORY What Do We Mean When We Say, “We Are Not Halachic”? . 9 Leon A. Morris Halachah in Reform Theology from Leo Baeck to Eugene B . Borowitz: Authority, Autonomy, and Covenantal Commandments . 17 Rachel Sabath Beit-Halachmi The CCAR Responsa Committee: A History . 40 Joan S. Friedman Reform Halachah and the Claim of Authority: From Theory to Practice and Back Again . 54 Mark Washofsky Is a Reform Shulchan Aruch Possible? . 74 Alona Lisitsa An Evolving Israeli Reform Judaism: The Roles of Halachah and Civil Religion as Seen in the Writings of the Israel Movement for Progressive Judaism . 92 David Ellenson and Michael Rosen Aggadic Judaism . 113 Edwin Goldberg Spring 2020 i CONTENTS Talmudic Aggadah: Illustrations, Warnings, and Counterarguments to Halachah . 120 Amy Scheinerman Halachah for Hedgehogs: Legal Interpretivism and Reform Philosophy of Halachah . 140 Benjamin C. M. Gurin The Halachic Canon as Literature: Reading for Jewish Ideas and Values . 155 Alyssa M. Gray APPLIED HALACHAH Communal Halachic Decision-Making . 174 Erica Asch Growing More Than Vegetables: A Case Study in the Use of CCAR Responsa in Planting the Tri-Faith Community Garden . 186 Deana Sussman Berezin Yoga as a Jewish Worship Practice: Chukat Hagoyim or Spiritual Innovation? . 200 Liz P. G. Hirsch and Yael Rapport Nursing in Shul: A Halachically Informed Perspective . 208 Michal Loving Can We Say Mourner’s Kaddish in Cases of Miscarriage, Stillbirth, and Nefel? . 215 Jeremy R. -

4. Asep Iqbal

Religió: Jurnal Studi Agama-agama ISSN: (p) 2088-6330; (e) 2503-3778 Vol. 6, No. 2 (2016); pp. 207-229 Varied Impacts of Globalization on Religion in a Contemporary Society Asep Muhamad Iqbal Institut Agama Islam Negeri Palangka Raya, Indonesia and Asia Research Centre, Murdoch University, Australia [email protected] Abstract This article discusses the current situation of religion caused by the forces of globalization by analyzing the developing phenomenon related to religion in contemporary society. It argues that globalization has a mixed impact on religion in ways that lead to the opposing view of secularist scholars that religion will be diminished. Apparently, religion has experienced a revival in many parts of the world, mainly in the form of religious fundamentalism. Problems and challenges posed by globalization, such as the environmental crisis and secular society have provided the opportunity and the power to religion to revitalize itself and to transform themselves into a religion with a new form that has a role and a new identity. Furthermore, globalization may lead to the decline of organized religion in modern society and certain intellectual subculture, but it does not cause the death of religion in private life. This is in line with the emergence of the phenomenon of “believing without belonging”. In short, globalization has helped to transform the religion itself and changed its strategy to address the problems and challenges of globalization to create “world de- secularization”. [Artikel ini membahas keadaan mutakhir agama yang diakibatkan oleh kekuatan-kekuatan globalisasi dengan melakukan analisa atas fenomena yang sedang berkembang terkait agama dalam masyarakat kontemporer. -

OF 15Th 2003 Rabbinic and Lay Communal Authority.Pdf (934.2Kb)

Rabbinic and Lay Communal Authority edited by Suzanne Last Stone Robert S. Hirt, Series Editor THE MICHAEL SCHARF PUBLICATION TRUST of the YESHIVA UNIVERSITY PRESs New York forum 15 r08 draft 7b balanced.iiii iii 31/12/2006 11:47:12 THE ORTHODOX FORUM The Orthodox Forum, initially convened by Dr. Norman Lamm, Chancellor of Yeshiva University, meets each year to consider major issues of concern to the Jewish community. Forum participants from throughout the world, including academicians in both Jewish and secular fields, rabbis,rashei yeshivah, Jewish educators, and Jewish communal professionals, gather in conference as a think tank to discuss and critique each other’s original papers, examining different aspects of a central theme. The purpose of the Forum is to create and disseminate a new and vibrant Torah literature addressing the critical issues facing Jewry today. The Orthodox Forum gratefully acknowledges the support of the Joseph J. and Bertha K. Green Memorial Fund at the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary established by Morris L. Green, of blessed memory. The Orthodox Forum Series is a project of the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary, an affiliate of Yeshiva University forum 15 r08 draft 7b balanced.iii ii 31/12/2006 11:47:12 Copyright © 2006 Yeshiva University Press Typeset by Jerusalem Typesetting, www.jerusalemtype.com * * * Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Orthodox Forum (15th : 2003 : New York, N.Y.) Rabbinic and lay communal authority / edited by Suzanne Last Stone. p. cm. – (Orthodox forum series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-88125-953-7 1. Rabbis – Office – Congresses. -

Descendants of the Anusim (Crypto-Jews) in Contemporary Mexico

Descendants of the Anusim (Crypto-Jews) in Contemporary Mexico Slightly updated version of a Thesis for the degree of “Doctor of Philosophy” by Schulamith Chava Halevy Hebrew University 2009 © Schulamith C. Halevy 2009-2011 This work was carried out under the supervision of Professor Yom Tov Assis and Professor Shalom Sabar To my beloved Berthas In Memoriam CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................7 1.1 THE PROBLEM.................................................................................................................7 1.2 NUEVO LEÓN ............................................................................................................ 11 1.2.1 The Original Settlement ...................................................................................12 1.2.2 A Sephardic Presence ........................................................................................14 1.2.3 Local Archives.......................................................................................................15 1.3 THE CARVAJAL TRAGEDY ....................................................................................... 15 1.4 THE MEXICAN INQUISITION ............................................................................. 17 1.4.1 José Toribio Medina and Alfonso Toro.......................................................17 1.4.2 Seymour Liebman ...............................................................................................18 1.5 CRYPTO‐JUDAISM -

1 Beginning the Conversation

NOTES 1 Beginning the Conversation 1. Jacob Katz, Exclusiveness and Tolerance: Jewish-Gentile Relations in Medieval and Modern Times (New York: Schocken, 1969). 2. John Micklethwait, “In God’s Name: A Special Report on Religion and Public Life,” The Economist, London November 3–9, 2007. 3. Mark Lila, “Earthly Powers,” NYT, April 2, 2006. 4. When we mention the clash of civilizations, we think of either the Spengler battle, or a more benign interplay between cultures in individual lives. For the Spengler battle, see Samuel P. Huntington, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996). For a more benign interplay in individual lives, see Thomas L. Friedman, The Lexus and the Olive Tree (New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1999). 5. Micklethwait, “In God’s Name.” 6. Robert Wuthnow, America and the Challenges of Religious Diversity (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005). “Interview with Robert Wuthnow” Religion and Ethics Newsweekly April 26, 2002. Episode no. 534 http://www.pbs.org/wnet/religionandethics/week534/ rwuthnow.html 7. Wuthnow, America and the Challenges of Religious Diversity, 291. 8. Eric Sharpe, “Dialogue,” in Mircea Eliade and Charles J. Adams, The Encyclopedia of Religion, first edition, volume 4 (New York: Macmillan, 1987), 345–8. 9. Archbishop Michael L. Fitzgerald and John Borelli, Interfaith Dialogue: A Catholic View (London: SPCK, 2006). 10. Lily Edelman, Face to Face: A Primer in Dialogue (Washington, DC: B’nai B’rith, Adult Jewish Education, 1967). 11. Ben Zion Bokser, Judaism and the Christian Predicament (New York: Knopf, 1967), 5, 11. 12. Ibid., 375. -

1 the Paul and Dorothy Grob Lecture on American Jewish Life the Nuremberg Trials at 75

The Paul and Dorothy Grob Lecture on American Jewish Life The Nuremberg Trials at 75: Lessons and Legacies April 6, 2021 Professor Martha Minow (Harvard Law School) This transcript has been edited for clarity. James Loeffler [JL] [00:00:08]: Good evening. My name is James Loeffler and I am a professor of history here at the University of Virginia, as you can see virtually behind me. I also serve as the Ida and Nathan Kolodiz Director of the Jewish Studies Program here at UVA. We are, if you’re not familiar with us, a multidisciplinary program that explores Judaism and Jewish historical experience through a combination of research, pedagogy, that is, teaching, and programing, which is one of the reasons we are gathered here tonight. If you want to know more about what we do, you are welcome to visit us online at www.jewishstudies.as.virginia.edu. You can also find a link there to get onto our mailing list for other programs like this that we do all the time. Now, as I mentioned to you, one of our core aims at the University of Virginia and in the Jewish Studies Program is to engage with critical issues of our day and our society, particularly as they intersect with Jewish themes and themes of Jewish history. In that regard, we’re very proud tonight to introduce to you the latest in our installment of Lectures in Paul and Dorothy Grob Memorial Lecture series on American Jewish Life. This is supported through the generosity of Dr. Mayer Grob, an alumnus of the University, and his wife, Dr. -

Maharam of Padua V. Giustiniani; the Sixteenth-Century Origins of the Jewish Law of Copyright

Draft: July 2007 44 Houston Law Review (forthcoming 2007) Maharam of Padua v. Giustiniani; the Sixteenth-Century Origins of the Jewish Law of Copyright Neil Weinstock Netanel* Copyright scholars are almost universally unaware of Jewish copyright law, a rich body of copyright doctrine and jurisprudence that developed in parallel with Anglo- American and Continental European copyright laws and the printers’ privileges that preceded them. Jewish copyright law traces its origins to a dispute adjudicated some 150 years before modern copyright law is typically said to have emerged with the Statute of Anne of 1709. This essay, the beginning of a book project about Jewish copyright law, examines that dispute, the case of the Maharam of Padua v. Giustiniani. In 1550, Rabbi Meir ben Isaac Katzenellenbogen of Padua (known by the Hebrew acronym, the “Maharam” of Padua) published a new edition of Moses Maimonides’ seminal code of Jewish law, the Mishneh Torah. Katzenellenbogen invested significant time, effort, and money in producing the edition. He and his son also added their own commentary on Maimonides’ text. Since Jews were forbidden to print books in sixteenth- century Italy, Katzenellenbogen arranged to have his edition printed by a Christian printer, Alvise Bragadini. Bragadini’s chief rival, Marc Antonio Giustiniani, responded by issuing a cheaper edition that both copied the Maharam’s annotations and included an introduction criticizing them. Katzenellenbogen then asked Rabbi Moses Isserles, European Jewry’s leading juridical authority of the day, to forbid distribution of the Giustiniani edition. Isserles had to grapple with first principles. At this early stage of print, an author- editor’s claim to have an exclusive right to publish a given book was a case of first impression.