Mapping Museums Project Interview Transcript Name: Richard Larn Role

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6 Romano-British (AD 43 – 410)

Isles of Scilly Historic Environment Research Framework: Resource Assessment and Research Agenda 6 Romano-British (AD 43 – 410) Edited by Charles Johns from contributions from Sarnia Butcher, Kevin Camidge, Dan Charman, Ralph Fyfe, Andy M Jones, Steve Mills, Jacqui Mulville, Henrietta Quinnell, and Paul Rainbird. 6.1 Introduction Although Scilly was a very remote part of the Roman Empire it occupied a pivotal position on the Atlantic façade along the routes of trade and cultural interchange between Brittany and Western Britain; unlike Cornwall, however, it was not a source of streamed tin. The cultural origins of Roman Scilly are rooted in the local Iron Age but sites can be identified which reflect the cult practices of the wider Roman world. Charles Thomas (1985, 170-2) envisaged Roman Scilly as a place of pilgrimage, dominated by a shrine to a native marine goddess at Nornour in the Eastern Isles. The rich Roman finds from that site are among the most iconic and enigmatic emblems of Scilly’s archaeological heritage. The main characteristics of Scilly’s Romano-British (AD 43 to AD 410) resource are summarised in this review. Fig 6.1 Iron Age and Romano-British sites recorded in the Scilly HER 6.2 Landscape and environmental background Results from the Lyonesse Project (Charman et al 2012) suggest that the present pattern of islands was largely formed by this period, although the intertidal zone was much greater in extent (Fig 6.2). Radiocarbon dating and environmental analysis of the lower peat deposit sample from Old Town Bay, St Mary’s, i n 1997 indicated that from the Late Iron Age to the early medieval period the site consisted of an area of shallow freshwater surrounded by a largely open landscape with arable fields and pasture bordering the wetland (Ratcliffe and Straker 1998, 1). -

Rapid Coastal Zone Assessment for the Isles of Scilly 2004

A Report for English Heritage Rapid Coastal Zone Assessment for The Isles of Scilly Charles Johns Richard Larn Bryn Perry Tapper May 2004 Report No: 2004R030 HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SERVICE Environment and Heritage, Planning Transportation and Estates, Cornwall County Council Kennall Building, Old County Hall, Station Road, Truro, Cornwall, TR1 3AY tel (01872) 323603 fax (01872) 323811 E-mail [email protected] 1 www.cornwall.gov.uk Acknowledgements This study was commissioned by English Heritage. Ian Morrison, Inspector of Ancient Monuments and Fachtna McAvoy, the Project Officer, provided guidance and support throughout, advice and help was also given by Vanessa Straker, South-West Regional Scientific Officer, Ian Oxley, Head of Maritime Archaeology, Annabel Lawrence, Archaeologist (Maritime) and Dave Hooley of the Characterisation Team. Help with the historical research was provided by various individuals and organisations, in particular: Amanda Martin and Sarnia Butcher of the Isles of Scilly Museum; Sophia Exelby, Receiver of Wreck; Sandra Gibson of Gibsons of Scilly; Adrian Webb, Research Manager, Hydrographic Data Centre, UKHO, Taunton; Ron Openshaw of the Bartlett Library, National Maritime Museum, Falmouth; Cornwall County Council’s Library Service and the Helston branch library. David Graty at the National Monument Record and June Dillon at the United Kingdom Hydrographic Office provided advice and help obtaining shipwreck information. Underwater images east of the Bristows, St Martin’s were collected by Dave Parry during a Plymouth Marine Laboratory research expedition in March 2003, funded by DEFRA through projects AE1137 and CDEP 84/5/295 for rapid assessment of marine biodiversity (RAMBLERS) External consultants for the project were: Richard Larn who provided maritime advice and expertise and Gill Arbery, Isles of Scilly Conservation Officer and English Heritage Field Monument warden who facilitated the consultation exercise and advised on conservation issues. -

Militaria Postal Bids Sale

MMiilliittaarriiaa PPoossttaall BBiiddss SSaallee 665566 Bids close 5pm. WWeeddnneessddaayy,, 2233rd JJuullyy,, 22001144 Index Lots 1 – 3646 Badges – Australia 1 - 569 Books By Subject 2149 - 2333 Great Britain 572 - 841 Germany 2344 - 2448 Germany 850 - 1102 Other 2466 - 2495 Other World 1103 - 1325 Uniforms 2496 - 2598 Medals – Australia 1326 - 1353 Headgear 2599 - 2724 Great Britain 1354 - 1444 Equipment 2725 - 2949 Other World 1455 - 1783 Equipment – German 2950 - 2982 Police - Australian & World 1784 - 1819 Guns andOrdnance 2983 - 3035 Antiquities 1821 - 1835 Bayonets 3036 - 3066 Artifacts 1836 - 1843 Swords 3067 - 3085 Bits & Pieces 1844 - 1925 Knives 3086 - 3094 Books – Australian 1926 - 2132 Ephemera 3095 - 3646 Great Britain 2133 - 2148 Viewing at I S Wright premises: 208 Sturt St, Ballarat, Victoria Monday - Tuesday 21st – 22nd July, 2014 9:00am – 4:30 pm Wednesday 23rd July, 2014 9:00am – 3.30pm Viewing other times may be possible, in all cases 24 hrs notice would be appreciated. I S Wright Militaria : 208 Sturt St, Ballarat Victoria, Australia, 3350. : +61 (0)3 5333 3476 FAX: +61 (0)3 5331 6426 Email: [email protected] web: www.iswright.com.au SYDNEY BALLARAT BALLARAT Proprietor: Office Manager: Despatch/Shipping: Stewart Wright David Riley Sharon Orr Office Administration: Militaria Describers : Internet Sales: Sabine Wincote David Riley Adam Werry Derek Brosnan Grant Luke Catalogue Production: Mark Broemmer Tseng Chiung-yao Other I S Wright Group Businesses Dealing In Militaria I S Wright Status International I S Wright I S Wright Shop 23 Adelaide Arcade 1st Floor, 262 Castlereagh St 241 Lonsdale St 3rd Floor, 262 Castlereagh St Rundle Mall SYDNEY MELBOURNE SYDNEY ADELAIDE, SA 5000 NSW 2000. -

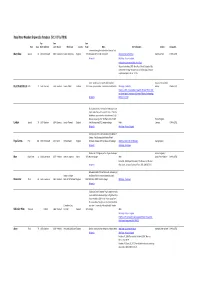

Royal Navy Wooden Shipwrecks Database (V1.3 07 Jul 2018)

Royal Navy Wooden Shipwrecks Database (V1.3 07 Jul 2018) Year Year Year Rate Guns Built Built Yard Lost Manner Where Lost Country Found Notes Site Publications Contact Designation Foundered during the Battle of the Solent in 1545. Mary Rose Second 91 1509 Portsmouth 1545 Foundered Solent, Hampshire England 1971 Excavated 1971 ‐ 1982, 2003‐2005 Web Site ‐ Mary Rose Trust Mary Rose Trust POWA (1973) Wikipedia Web Page ‐ Historic England Publications List from the Mary Rose Trust Wessex Archaeology, 2006, Mary Rose, Solent, Designated Site Assessment: Heritage Management and Archaeological Report, unpublished report ref: 53111.02kk Swan. Sunk in a severe storm while in service. Historic Scotland, Colin Duart Point Wreck Fifth 32 1641 Unknown 1653 Wrecked Sound of Mull Scotland 1979 Found by a naval diver. Excavated by Colin Martin Web Page ‐ CANMORE Martin POWA (1973) Martin C., 1995, A Cromwellian shipwreck off Duart Point, Mull: an interim report, International Journal of Nautical Archaeology Wikipedia (IJNA) 24:1, 15‐32 Built during the Interregnum, she formed part of an English Squadron sent to collect Charles II from the Netherlands and restore him to his throne in 1658. Blew up on passage from Chatham in March 1665. Historic England, London Second 76 1657 Chatham 1664 Blown up Lee (on Thames) England Partially excavated 2015; modern salvage Web ‐ Licensee POWA (1973) Wikipedia Web Page ‐ Historic England Destroyed by the fire and sank during the Battle of Solebay. Possibly located by Historic Wreck Royal James First 102 1672 Portsmouth 1672 Burnt Off Southwold England Recovery, assessed 2009 by Wessex Archaeology Web Site ‐ Historic Wreck Recovery George Spence Wikipedia Web Page ‐ Pastscape Struck rocks off Anglesey in thick fog and broke up. -

Wessex Archaeology

Wessex Archaeology Early Ships and Boats (Prehistory to 1840) EH 6440 Strategic Desk-based Assessment Ref: 84130.01 January 2013 EARLY SHIPS AND BOATS (PREHISTORY TO 1840) EH 6440 STRATEGIC DESK-BASED ASSESSMENT Prepared by: Wessex Archaeology Portway House Old Sarum Park Salisbury WILTSHIRE SP4 6EB Prepared for: English Heritage Ref: 84130.01 January 2013 © Wessex Archaeology Limited 2013 Wessex Archaeology Ltd is a company limited by guarantee registered in England, company number 1712772. It is also a Charity registered in England and Wales, number 287786; and in Scotland, Scottish Charity number SC042630. Our registered office is at Portway House, Old Sarum Park, Salisbury, Wilts SP4 6EB. Early Ships and Boats (Prehistory to 1840) EH 6440 Strategic Desk-based Assessment ref. 84130.01 EARLY SHIPS AND BOATS (PREHISTORY TO 1840) EH 6440 STRATEGIC DESK-BASED ASSESSMENT Ref: 84130.01 Early Ships and Boats (Prehistory to 1840) Title: Strategic Desk-based Assessment Principal Author(s): Victoria Cooper Managed by: Nikki Cook Origination date: January 2013 Date of last revision: November 2012 Version: .01 Wessex Archaeology QA: Nikki Cook Status: Final Updated draft to incorporate comments from Summary of changes: English Heritage Associated reports: Client Approval: i Early Ships and Boats (Prehistory to 1840) EH 6440 Strategic Desk-based Assessment ref. 84130.01 EARLY SHIPS AND BOATS (PREHISTORY TO 1840) EH 6440 STRATEGIC DESK-BASED ASSESSMENT Ref: 84130.01 Summary The Early Ships and Boats project comprises a strategic desk-based assessment of known and dated vessels from the Prehistoric period up to 1840. At present, very few boats and ships are offered statutory protection in England in comparison to the large numbers of known and dated wrecks and even greater numbers of recorded losses of boats and ships in English waters. -

Sir Cloudesley Shovell Crayford’S Famous Admiral

Sir Cloudesley Shovell Crayford’s Famous Admiral orn in the village of Cockthorpe in the County of Norfolk in B1650, Cloudesley Shovell rose from a humble birth to become one of the leading and finest admirals of the age. He left home aged 12 to be a cabin boy under Sir Christopher Myngs, and was soon in action off the West Indies against the Spanish treasure ships. He showed his metal at an early age during the Four Days War against the Dutch when he volunteered in the heat of the battle to swim from ship to ship bearing a message for assistance which turned defeat into victory. When Myngs was fatally injured, Cloudesley continued his service under Sir John Narbrough. He distinguished himself when he confronted the Dey of Algiers after the Algerians captured a number of English ships and enslaved their crews. Cloudesley set fire to the Algerian ships in their harbour and forced the release of the slaves, also securing the sum of £80,000 in reparations. Sir Cloudesley Shovell (1650-1707). He distinguished himself at the Battle of Bantry Bay during the Artist: Michael Dahl March 1702 - January 1705 Credit: Royal Museums Greenwich BHC3025 ‘Glorious Revolution’ of 1689, after which William III & Mary II ascended to the throne of England. King William knighted him after the battle, and the following year (1690) he was promoted to Admiral of the Blue. At the Battle of Barfleur, the invading French fleet attempting to restore James II to the English throne was defeated, with much of the credit going to Sir Cloudesley. -

A Look at Two Groundings of Naval Vessels Separated by Over Two

Does History Ever Repeat Itself? A Look at Two Groundings of Naval Vessels Separated by Over Two Centuries. Derek McCann Abstract This narrative outline of two very similar naval disasters, separated by over two centuries, shows how history can be repeated and for very similar reasons. It demonstrates the frailty of human decision-making, using a brain that has scarcely evolved over the past 10,000 years, and it attempts to explain some of the mental aberrations behind human error. Experience is no guarantor of exactitude, and in fact, seasoned leaders are often guilty of recklessness while their juniors, fearful of retribution, take a good deal more care over their decisions1. Going home Whether he’s a first tripper or a seasoned tar, no sailor has immunity to that frisson in the gut resulting in heightend mood and a feeling of benevolence towards all, even the cook. The affliction is known as “Channel Fever”. The year was 1707 and the battle weary seamen and officers on board the ships of Admiral Sir Cloudesly FIGURE 1 ADMIRAL CLOUDESELY SHOVALL. NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY. Shovell’s Royal Navy squadron all shared the same HTTPS://COMMONS.WIKIMEDIA.ORG/WIKI/FILE:WP_ CLOUDESLEY_SHOVELL.JPG 32 CORIOLIS VOLUME 10, NUMBER 1, 2020 reaction, whether they admitted to it or not, as orders were received for the fleet to return to England. Not quite two months previously, on the 22nd August2, they had manned the guns outside the harbor of Toulon, while on shore the Allied armies had attempted to take the town – unsuccessfully as it turned out. -

Charles Miller Ltd Miller Charles Maritime and Scientific Models, Instruments & Art & Instruments Models, Scientific and Maritime

7 Charles Miller Ltd Charles Miller Charles Miller Ltd Maritime and Scientific Models, Instruments & Art London Wednesday 20th April 2011 London Wednesday 20th April 2011 London Wednesday Charles Miller Ltd 25 Blythe Road, London, W14 0PD Tel: +44 (0) 207 806 5530 • Fax: +44 (0) 207 806 5531 • Email: [email protected] Auction Enquiries and Information Sale Number: 007 Code name: Princess Enquiries Catalogue Tel: +44 (0) 207 806 5530 Charles Miller £15 plus postage Fax: +44 (0) 207 806 5531 Clair Boluski Email: [email protected] Historical Consultant Online Catalogue Michael Naxton www.charlesmillerltd.com www.antiquestradegazette.com/charlesmillerltd Charles Miller Ltd 25 Blythe Road London W14 0PD Listen to the Auction Live: +44(0)20 7806 5535 Bid Live via the-saleroom.com: See page 96 for details Important Information for Buyers All Lots are offered subject to Charles Miller Ltd.’s Conditions of Business and to reserves. The Conditions of Business for Buyers are published at the end of the catalogue. Estimates are published as a guide only and are subject to review. The actual hammer price of a lot may well be higher or lower than the range of figures given and there are no fixed “starting prices”. A Buyer’s Premium of 20% is applicable to all lots in this sale. Excepting lots sold under Temporary Import Rules which are marked with the symbol ‡ (see below), the Buyer’s Premium is subject to VAT at the standard rate (currently 20%). Lots offered for sale under the auctioneer’s margin scheme and VAT on the Buyer’s Premium is payable by all buyers.