Testing a New Approach on Koster Dikes Dolerites with Incipient Amphibolite-Facies Overprint

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geochemistry This

TORONTOTORONTO Vol. 8, No. 4 April 1998 Call for Papers GSA TODAY — page C1 A Publication of the Geological Society of America Electronic Abstracts Submission — page C3 Antarctic Neogene Landscapes—In the 1998 Registration Refrigerator or in the Deep Freeze? Annual Issue Meeting — June GSA Today Introduction The present Molly F. Miller, Department of Geology, Box 117-B, Vanderbilt Antarctic landscape undergoes very University, Nashville, TN 37235, [email protected] slow environmental change because it is almost entirely covered by a thick, slow-moving ice sheet and thus effectively locked in a Mark C. G. Mabin, Department of Tropical Environmental Studies deep freeze. The ice sheet–landscape system is essentially stable, and Geography, James Cook University, Townsville, Queensland 4811, Australia, [email protected] Antarctic—Introduction continued on p. 2 Atmospheric Transport of Diatoms in the Antarctic Sirius Group: Pliocene Deep Freeze Arjen P. Stroeven, Department of Quaternary Research, Stockholm University, S-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden Lloyd H. Burckle, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University, Palisades, NY 10964 Johan Kleman, Department of Physical Geography, Stockholm University, S-106, 91 Stockholm, Sweden Michael L. Prentice, Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans, and Space, University of New Hampshire, Durham, NH 03824 INTRODUCTION How did young diatoms (including some with ranges from the Pliocene to the Pleistocene) get into the Sirius Group on the slopes of the Transantarctic Mountains? Dynamicists argue for emplacement by a wet-based ice sheet that advanced across East Antarctica and the Transantarctic Mountains after flooding of interior basins by relatively warm marine waters [2 to 5 °C according to Webb and Harwood (1991)]. -

The Origin of the Columbia River Flood Basalt Province: Plume Versus Nonplume Models

The Origin of the Columbia River Flood Basalt Province: Plume versus Nonplume Models Peter R. Hooper1, Victor E. Camp2, Stephen P. Reidel3 and Martin E. Ross4 1 Dept of Geology, Washington State University, Pullman, WA 99164 and Open University, Milton Keynes, MK7 6AA, U.K. 2 Dept of Geological Sciences, San Diego State University, San Diego, CA 92182 3 Washington State University Tri-Cities, Richland, Washington 99352 4 Dept of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Northeastern University, 360 Huntington Av., Boston, MA 02115 ABSTRACT As a contribution to the plume-nonplume debate we review the tectonic setting in which huge volumes of monotonous tholeiite of the Columbia River flood basalt province of the Pacific Northwest, USA, were erupted. We record the time-scale and the locations of these eruptions, estimates of individual eruption volumes, and discuss the mechanisms of sheet- flow emplacement, all of which bear on the ultimate origin of the province. An exceptionally large chemical and isotopic data base is used to identify the various mantle sources of the basalt and their subsequent evolution in large lower crustal magma chambers. We conclude by discussing the available data in light of the various deep mantle plume and shallow mantle models recently advocated for the origin of this flood basalt province and we argue that the mantle plume model best explains such an exceptionally large volume of tholeiitic basalt erupted over an unusually short period and within such a restricted area. 1 INTRODUCTION Advocates of mantle plumes have long considered continental flood basalt provinces to be one of the most obvious expressions of plume activity (Campbell and Griffiths, 1990; Richards et al., 1989). -

Provided for Non-Commercial Research and Educational Use. Not for Reproduction, Distribution Or Commercial Use

Provided for non-commercial research and educational use. Not for reproduction, distribution or commercial use. This article was originally published in the Treatise on Geophysics, published by Elsevier and the attached copy is provided by Elsevier for the author’s benefit and for the benefit of the author’s institution, for non-commercial research and educational use including use in instruction at your institution, posting on a secure network (not accessible to the public) within your institution, and providing a copy to your institution’s administrator. All other uses, reproduction and distribution, including without limitation commercial reprints, selling or licensing copies or access, or posting on open internet sites are prohibited. For exceptions, permission may be sought for such use through Elsevier’s permissions site at: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/permissionusematerial Information taken from the copyright line. The Editor-in-Chief is listed as Gerald Schubert and the imprint is Academic Press. Author's personal copy 7.09 Hot Spots and Melting Anomalies G. Ito, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI, USA P. E. van Keken, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA ª 2007 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. 7.09.1 Introduction 372 7.09.2 Characteristics 373 7.09.2.1 Volcano Chains and Age Progression 373 7.09.2.1.1 Long-lived age-progressive volcanism 373 7.09.2.1.2 Short-lived age-progressive volcanism 381 7.09.2.1.3 No age-progressive volcanism 382 7.09.2.1.4 Continental hot spots 383 7.09.2.1.5 The hot-spot reference frame 386 -

Copyrighted Material

Index Page numbers in italics refer to fi gures; those in bold to tables Acasta gneisses 347 sea fl oor divided into 84 diversity of 288–9 accretionary orogens, structure 287, 309, Aleutian accretionary prism growth latest phase of compression 289 336–42 rate 267 Andean foreland, styles of tectonic active, seismic refl ection profi les 295, 315, Aleutian arc, focal mechanism solutions of shortening 292, 292, 293, 294 340, 342 earthquakes 256, 257 foreland basement thrusts 292, 293 Canadian Cordillera 336–7, 338, 339, 341, Aleutian–Alaska arc, prominent gap in segmentation of foreland 292, 294 376 seismicity 259, 261 thick-skinned and thin-skinned fold and common features of 338, 340, 502 alkaline series, includes shoshonitic thrust belts 292, 293 western North America 336, 337 lavas 271 Andean-type subduction, specifi c types of accretionary prisms 251, 264–9, 270 Alpine Fault, New Zealand 228–30, 338 deposit 417–18 accumulation of sediments including accommodation of oblique slip 244, 245, backarc environment, granite belts with olistostromes 267 246 tin and tungsten 417–18 creation of mélange 268 Breaksea Basin once continuous with stratabound copper sulfi des 417 décollement 264, 266 Dagg Basin 220, 221, 222 Andes, central 301–2 sliding on 267 central segment, weakly/non-partitioned arcuate shape (orocline) 294 deformation front 264 style of transpressional evolution of shortening (model) 300 development of 243, 244 deformation 213, 223 fl at and steep subduction zones 289, 291 and development of forearc basin 267 change in relative plate -

And the Digital Data Files Contained on It (The “Content”), Is Governed by the Terms Set out on This Page (“Terms of Use”)

ISBN 978-1-4249-9924-8 [DVD] ISBN 978-1-4249-9925-5[ZIP FILE] THESE TERMS GOVERN YOUR USE OF THIS PRODUCT Your use of this electronic information product (“EIP”), and the digital data files contained on it (the “Content”), is governed by the terms set out on this page (“Terms of Use”). By opening the EIP and viewing the Content , you (the “User”) have accepted, and have agreed to be bound by, the Terms of Use. EIP and Content: This EIP and Content is offered by the Province of Ontario’s Ministry of Northern Development and Mines (MNDM) as a public service, on an “as-is” basis. Recommendations and statements of opinions expressed are those of the author or authors and are not to be construed as statement of government policy. You are solely responsible for your use of the EIP and its Content. You should not rely on the Content for legal advice nor as authoritative in your particular circumstances. Users should verify the accuracy and applicability of any Content before acting on it. MNDM does not guarantee, or make any warranty express or implied, that the Content is current, accurate, complete or reliable or that the EIP is free from viruses or other harmful components. MNDM is not responsible for any damage however caused, which results, directly or indirectly, from your use of the EIP or the Content. MNDM assumes no legal liability or responsibility for the EIP or the Content whatsoever. Links to Other Web Sites: This EIP or the Content may contain links, to Web sites that are not operated by MNDM. -

Regional Dike Swarm Emplacement of Silicic Arc Magma in the Peninsular Ranges Batholith

REGIONAL DIKE SWARM EMPLACEMENT OF SILICIC ARC MAGMA IN THE PENINSULAR RANGES BATHOLITH: THE SAN MARCOS DIKE SWARM (SMDS) OF NORTHERN BAJA CALIFORNIA Phil FARQUHARSON (presenter), David L. KIMBROUGH, and R. Gordon GASTIL, Department of Geological Sciences, San Diego State University Rancho San Marcos A densely intruded, northwest-striking, predominantly silicic regional dike The SMDS occurs entirely within the western province of the PRB, which is charac- swarm is exposed over an approximately 100 km-long segment in the terized by gabbro-tonalite-granodiorite plutons with primitive island arc geochemical west-central portion of the Cretaceous Peninsular Ranges batholith (PRB) affinities (DePaolo, 1981; Silver & Chappell, 1988; Todd et al., 1988, 1994), and in northern Baja California. Dike compositions range from basalt to rhyo- Rancho El Campito U/Pb zircon ages of 120-100 Ma. The extent of the swarm is shown schematically lite and are locally strongly bimodal. The swarm is intruded into two main N on the Gastil et al. (1975) 1:250 000 map of Baja California. units; 1) Triassic-Jurassic (?) turbidite flysch and 2) older, presumably pre- The swarm is intruded into two main units; 1) Triassic-Jurassic(?) turbidite flysch of 120 Ma batholithic rocks. Cross-cutting field relationships and a prelimi- the Rancho Vallecitos Formation (Reed, 1993) that is correlated to Julian Schist and nary U-Pb zircon age of 120±1 Ma clearly establish the swarm as an inte- Middle Jurassic Bedford Canyon Formation north of the border, and 2) older, pre- gral feature in the magmatic evolution of the PRB. Surprisingly, despite Agua Blanca Fault sumably pre-120 Ma batholithic rocks for which little data is currently available. -

Field-Trip Guide to the Vents, Dikes, Stratigraphy, and Structure of the Columbia River Basalt Group, Eastern Oregon and Southeastern Washington

Field-Trip Guide to the Vents, Dikes, Stratigraphy, and Structure of the Columbia River Basalt Group, Eastern Oregon and Southeastern Washington Scientific Investigations Report 2017–5022–N U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. Palouse Falls, Washington. The Palouse River originates in Idaho and flows westward before it enters the Snake River near Lyons Ferry, Washington. About 10 kilometers north of this confluence, the river has eroded through the Wanapum Basalt and upper portion of the Grande Ronde Basalt to produce Palouse Falls, where the river drops 60 meters (198 feet) into the plunge pool below. The river’s course was created during the cataclysmic Missoula floods of the Pleistocene as ice dams along the Clark Fork River in Idaho periodically broke and reformed. These events released water from Glacial Lake Missoula, with the resulting floods into Washington creating the Channeled Scablands and Glacial Lake Lewis. Palouse Falls was created by headward erosion of these floodwaters as they spilled over the basalt into the Snake River. After the last of the floodwaters receded, the Palouse River began to follow the scabland channel it resides in today. Photograph by Stephen P. Reidel. Field-Trip Guide to the Vents, Dikes, Stratigraphy, and Structure of the Columbia River Basalt Group, Eastern Oregon and Southeastern Washington By Victor E. Camp, Stephen P. Reidel, Martin E. Ross, Richard J. Brown, and Stephen Self Scientific Investigations Report 2017–5022–N U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior RYAN K. ZINKE, Secretary U.S. -

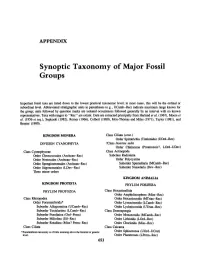

Synoptic Taxonomy of Major Fossil Groups

APPENDIX Synoptic Taxonomy of Major Fossil Groups Important fossil taxa are listed down to the lowest practical taxonomic level; in most cases, this will be the ordinal or subordinallevel. Abbreviated stratigraphic units in parentheses (e.g., UCamb-Ree) indicate maximum range known for the group; units followed by question marks are isolated occurrences followed generally by an interval with no known representatives. Taxa with ranges to "Ree" are extant. Data are extracted principally from Harland et al. (1967), Moore et al. (1956 et seq.), Sepkoski (1982), Romer (1966), Colbert (1980), Moy-Thomas and Miles (1971), Taylor (1981), and Brasier (1980). KINGDOM MONERA Class Ciliata (cont.) Order Spirotrichia (Tintinnida) (UOrd-Rec) DIVISION CYANOPHYTA ?Class [mertae sedis Order Chitinozoa (Proterozoic?, LOrd-UDev) Class Cyanophyceae Class Actinopoda Order Chroococcales (Archean-Rec) Subclass Radiolaria Order Nostocales (Archean-Ree) Order Polycystina Order Spongiostromales (Archean-Ree) Suborder Spumellaria (MCamb-Rec) Order Stigonematales (LDev-Rec) Suborder Nasselaria (Dev-Ree) Three minor orders KINGDOM ANIMALIA KINGDOM PROTISTA PHYLUM PORIFERA PHYLUM PROTOZOA Class Hexactinellida Order Amphidiscophora (Miss-Ree) Class Rhizopodea Order Hexactinosida (MTrias-Rec) Order Foraminiferida* Order Lyssacinosida (LCamb-Rec) Suborder Allogromiina (UCamb-Ree) Order Lychniscosida (UTrias-Rec) Suborder Textulariina (LCamb-Ree) Class Demospongia Suborder Fusulinina (Ord-Perm) Order Monaxonida (MCamb-Ree) Suborder Miliolina (Sil-Ree) Order Lithistida -

Giant Radiating Mafic Dyke Swarm of the Emeishan Large Igneous Province: Identifying the Mantle Plume Centre

doi: 10.1111/ter.12154 Giant radiating mafic dyke swarm of the Emeishan Large Igneous Province: Identifying the mantle plume centre Hongbo Li,1,2 Zhaochong Zhang,1 Richard Ernst,3,4 Linsu L€u,2 M. Santosh,1 Dongyang Zhang1 and Zhiguo Cheng1 1State Key Laboratory of Geological Processes and Mineral Resources, China University of Geosciences, Beijing 100083, China; 2Geologi- cal Museum of China, Beijing 100034, China; 3Department of Earth Sciences, Carleton University, Ottawa, ON K1S 5B6, Canada; 4Ernst Geosciences, 43 Margrave Avenue, Ottawa, ON K1T 3Y2, Canada ABSTRACT In many continental large igneous provinces, giant radiating and recognized six dyke sub-swarms, forming an overall dyke swarms are typically interpreted to result from the arri- radiating dyke swarm and converging in the Yongren area, val of a mantle plume at the base of the lithosphere. Mafic Yunnan province. This location coincides with the maximum dyke swarms in the Emeishan large igneous province (ELIP) pre-eruptive domal uplift, and is close to the locations of have not received much attention prior to this study. We high-temperature picrites. Our study suggests that the Yon- show that the geochemical characteristics and geochronologi- gren area may represent the mantle plume centre during the cal data of the mafic dykes are broadly similar to those of peak of Emeishan magmatism. the spatially associated lavas, suggesting they were derived from a common parental magma. Based on the regional geo- Terra Nova, 27, 247–257, 2015 logical data and our field observations, we mapped the spa- tial distribution patterns of mafic dyke swarms in the ELIP, ridge by a continent (Gower and swarms and their distributions pro- Introduction Krogh, 2002), edge-driven enhanced vide an opportunity to further test Large igneous provinces (LIPs) are mantle convection (King and Ander- the plume model for the ELIP. -

Instability of the Southern Canadian Shield During the Late Proterozoic 2 3 Kalin T

1 Instability of the southern Canadian Shield during the late Proterozoic 2 3 Kalin T. McDannella,b*, Peter K. Zeitlera, and David A. Schneiderc 4 5 aDepartment of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Lehigh University, 1 W. Packer Ave. Bethlehem PA, 18015 USA 6 7 bGeological Survey of Canada, Natural Resources Canada, 3303 – 33 St NW Calgary AB, T2L 2A7 Canada 8 9 cDepartment of Earth & Environmental Sciences, University of Ottawa, 25 Templeton Ave., Ottawa ON, K1N 6N5 10 Canada 11 12 *corresponding author: [email protected]; [email protected] 13 14 ABSTRACT 15 Cratons are generally considered to comprise lithosphere that has remained tectonically 16 quiescent for billions of years. Direct evidence for stability is mainly founded in the Phanerozoic 17 sedimentary record and low-temperature thermochronology, but for extensive parts of Canada, 18 earlier stability has been inferred due to the lack of an extensive rock record in both time and 19 space. We used 40Ar/39Ar multi-diffusion domain (MDD) analysis of K-feldspar to constrain 20 cratonic thermal histories across an intermediate (~150-350°C) temperature range in an attempt 21 to link published high-temperature geochronology that resolves the timing of orogenesis and 22 metamorphism with lower-temperature data suited for upper-crustal burial and unroofing 23 histories. This work is focused on understanding the transition from Archean-Paleoproterozoic 24 crustal growth to later intervals of stability, and how uninterrupted that record is throughout 25 Earth’s Proterozoic “Middle Age.” Intermediate-temperature thermal histories of cratonic rocks 26 at well-constrained localities within the southern Canadian Shield of North America challenge 27 the stability worldview because our data indicate that these rocks were at elevated temperatures 28 in the Proterozoic. -

7.09 Hot Spots and Melting Anomalies G

7.09 Hot Spots and Melting Anomalies G. Ito, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI, USA P. E. van Keken, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA ª 2007 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. 7.09.1 Introduction 372 7.09.2 Characteristics 373 7.09.2.1 Volcano Chains and Age Progression 373 7.09.2.1.1 Long-lived age-progressive volcanism 373 7.09.2.1.2 Short-lived age-progressive volcanism 381 7.09.2.1.3 No age-progressive volcanism 382 7.09.2.1.4 Continental hot spots 383 7.09.2.1.5 The hot-spot reference frame 386 7.09.2.2 Topographic Swells 387 7.09.2.3 Flood Basalt Volcanism 388 7.09.2.3.1 Continental LIPs 388 7.09.2.3.2 LIPs near or on continental margins 389 7.09.2.3.3 Oceanic LIPs 391 7.09.2.3.4 Connections to hot spots 392 7.09.2.4 Geochemical Heterogeneity and Distinctions from MORB 393 7.09.2.5 Mantle Seismic Anomalies 393 7.09.2.5.1 Global seismic studies 393 7.09.2.5.2 Local seismic studies of major hot spots 395 7.09.2.6 Summary of Observations 399 7.09.3 Dynamical Mechanisms 400 7.09.3.1 Methods 400 7.09.3.2 Generating the Melt 401 7.09.3.2.1 Temperature 402 7.09.3.2.2 Composition 402 7.09.3.2.3 Mantle flow 404 7.09.3.3 Swells 405 7.09.3.3.1 Generating swells: Lubrication theory 405 7.09.3.3.2 Generating swells: Thermal upwellings and intraplate hot spots 407 7.09.3.3.3 Generating swells: Thermal upwellings and hot-spot–ridge interaction 408 7.09.3.4 Dynamics of Buoyant Upwellings 410 7.09.3.4.1 TBL instabilities 410 7.09.3.4.2 Thermochemical instabilities 411 7.09.3.4.3 Effects of variable mantle properties 412 7.09.3.4.4 Plume -

EPSC 233: Earth and Life History

EPSC 233: Earth and Life History Galen Halverson Fall Semester, 2014 Contents 1 Introduction to Geology and the Earth System 1 1.1 The Science of Historical Geology . 1 1.2 The Earth System . 4 2 Minerals and Rocks: The Building Blocks of Earth 6 2.1 Introduction . 6 2.2 Structure of the Earth . 6 2.3 Elements and Isotopes . 7 2.4 Minerals . 9 2.5 Rocks . 10 3 Plate Tectonics 16 3.1 Introduction . 16 3.2 Continental Drift . 16 3.3 The Plate Tectonic Revolution . 17 3.4 An overview of plate tectonics . 20 3.5 Vertical Motions in the Mantle . 24 4 Geological Time and the Age of the Earth 25 4.1 Introduction . 25 4.2 Relative Ages . 25 4.3 Absolute Ages . 26 4.4 Radioactive dating . 28 4.5 Other Chronostratigraphic Techniques . 31 5 The Stratigraphic Record and Sedimentary Environments 35 5.1 Introduction . 35 5.2 Stratigraphy . 35 5.3 Describing and interpreting detrital sedimentary rocks . 36 6 Life, Fossils, and Evolution 41 6.1 Introduction . 41 6.2 Fossils . 42 6.3 Biostratigraphy . 44 6.4 The Geological Time Scale . 45 6.5 Systematics and Taxonomy . 46 6.6 Evolution . 49 6.7 Gradualism Versus Punctuated Equilibrium . 53 i ii 7 The Environment and Chemical Cycles 55 7.1 Introduction . 55 7.2 Ecology . 56 7.3 The Atmosphere . 57 7.4 The Terrestrial Realm . 61 7.5 The Marine Realm . 63 8 Origin of the Earth and the Hadean 66 8.1 Introduction . 66 8.2 Origin of the Solar System .