Pack Monadnock Raptor Observatory Fall 2018 Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Town of Temple, New Hampshire Planning Board

TOWN OF TEMPLE, NEW HAMPSHIRE PLANNING BOARD NOVEMBER 30, 2011 FINAL MINUTES OF PUBLIC MEETING Board members present: John Kieley, Randy Martin, Bruce Kullgren, Allan Pickman, Richard Whitcomb, and Rose Lowry Call to order by Pickman at 7:20 p.m. after a slight delay in setting up the PowerPoint presentation. Public forum on Large Wind Energy Systems: Lowry welcomed the audience of approximately 60 people and gave an overview of the meeting format. She asked that questions be held until after the initial presentation. Lowry then provided commentary to a PowerPoint display. She explained that Pioneer Green Energy has proposed a multi-tower wind farm project in the neighboring town of New Ipswich, and is also considering placement of 1 to 3 towers in Temple in the area of Kidder Mountain. She indicated planning is still in the preliminary stages. She said Temple is considered an abutter to the New Ipswich project due to regional impact. Even if no turbines are installed in Temple, all New Ipswich towers would be visible in Temple. Lowry stated New Ipswich already has a large wind energy zoning ordinance in place to regulate commercial wind, and now Temple is considering creation of such an ordinance. This would help maintain local control, protect the character of the town, safeguard public health and safety, preserve property values, and protect wildlife and the environment. She also said without any local control the state Site Evaluation Committee (SEC) could become involved, as well as the local Zoning Board of Adjustment (ZBA). Lowry next discussed turbine size and the amount of energy created. -

Agency Real Property Reports Required by Rsa 4

STATE OF NEW HAMPSHIRE AGENCY REAL PROPERTY REPORTS REQUIRED BY RSA 4:39-e FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED JUNE 30, 2019 4:39-e Real Property Owned or Leased by State Agencies; Reporting Requirement. I. On or before July 1, 2013, and biennially thereafter, each state agency, as defined in RSA 21-G:5, III, shall make a report identifying all real property owned or leased by the agency. For each parcel owned by the agency, the report shall include any reversion provisions, conservation or other easements, lease arrangements with third parties, and any other agreement that may affect the future sale of the property. For each parcel leased by the agency, the report shall include the lease term. II. Each state agency shall file the report with the governor, the senate president, the speaker of the house of representatives, the chairperson of the senate capital budget committee, the chairperson of the house public works and highways committee, the chairperson of the long range capital planning and utilization committee established in RSA 17-M:1, and the commissioner of the department of administrative services. III. The commissioner of the department of administrative services shall develop a standard format for agencies to use in submitting the report required under this section. The form of the report shall not be considered a rule subject to the provisions of RSA 541-A. (Source. 2012, 254:1, eff. June 18, 2012.) Introduction and Notes In developing a standard format for all agencies to use in submitting the report required by RSA 4:39-e, Administrative Services (DAS) staff designed and constructed a central state real property database to receive, store, maintain and manage information on all real property assets owned or leased by the State of New Hampshire, and from which all agency reports are generated. -

MOUNT WASHINGTON COG RAILWAY Constructed 1869

The American Society of Mechanical Engineers The American Society of Civil Engineers MOUNT WASHINGTON COG RAILWAY Constructed 1869 National Historic Mechanical and Civil Engineering Landmark June 26, 1976 MOUNT WASHINGTON COG RAILWAY Mount Washington, rising 6288 feet above sea level in the mountainous north country of New Hampshire, is the highest peak in the Northeast. The world's first cog railway ascends a western spur of the mountain between Burt and Ammonoosuc Ravines from the Marshfield Base Station which is almost 3600 feet below the summit. The railway is a tribute to the ingenuity and perseverance of its founder, a civil-mechanical engineer, Sylvester Marsh. History attributes the conception and the execution of the railway idea directly to Mr. Marsh. Indeed, his very actions personify the exacting requirements of the National Historic Engineering Landmark programs of The American Society of Civil Engineers and The American Society of Mechanical Engi- neers. The qualities of the Cog Railway are so impressive that, for the first time, two national engineering societies have combined their conclusions in order to designate the train system as a National Historic Mechanical and Civil Engineering Landmark. Sylvester Marsh was born in Campton, New Hampshire on September 30, 1803. When he was nineteen he walked the 150 miles to Boston in three days to seek a job. There he worked on a farm, returned home for a short time, and then again went to Boston where he entered the provision business. After seven years, he moved to Chicago, then a young town of about 300 settlers. From Chicago, Marsh shipped beef and pork to Boston as he developed into a founder of the meat packing industry in the midwestern city. -

Ownership History of the Mount Washington Summit1

STATE OF NEW HAMPSHIRE Inter-Department Communication DATE: July 23, 2018 FROM: K. Allen Brooks AT (OFFICE) Department of Justice Senior Assistant Attorney General Environmental Protection Bureau SUBJECT: Ownership of Mount Washington Summit TO: The Mount Washington Commission ____________________________________ Ownership History of the Mount Washington Summit1 The ownership history of the summit of Mount Washington is interwoven with that of Sargent’s Purchase, Thompson and Meserve’s Purchase, and numerous other early grants and conveyances in what is now Coos County. Throughout these areas, there has never been a shortage of controversy. Confusion over what is now called Sargent’s Purchase began as far back as 1786 when the Legislature appointed McMillan Bucknam to sell certain state lands. Bucknam conveyed land described as being southwest of Roger’s Location, Treadwell’s Location, and Wentworth’s 1 The following history draws extensively from several N.H. Supreme Court opinions (formerly called the Superior Court of Judicature of New Hampshire) and to a lesser extent from various deeds and third-party information, specifically – Wells v. Jackson Iron Mfg. Co., 44 N.H. 61 (1862); Wells v. Jackson Iron Mfg. Co., 47 N.H. 235 (1866); Wells v. Jackson Iron Mfg. Co., 48 N.H. 491 (1869); Wells v. Jackson Iron Co., 50 N.H. 85 (1870); Coos County Registry of Deeds – (“Book/Page”) B8/117; B9/241; B9/245; B9/246; B9/247; B9/249; B9/249; 12/170; 12/172; B15/122; B15/326; 22/28; B22/28; B22/29; 22/68; B25/255; B28/176; B28/334; B30/285; B30/287; -

Hike Leader Handbook

Excursions Committee New Hampshire Chapter Of the Appalachian Mountain Club Hike Leader Handbook February, 2016 AMC-NH Hike Leader Handbook Page 2 of 75. 2AMC–NH Chapter Excursions Committee Hike Leader Handbook Table of Contents Letter to New Graduates The Trail to Leadership – Part D Part 1 - Leader Requirements Part 2 – Hike Leader Bill of Rights Part 2a-Leader-Participant Communication Part 3 - Guidelines for Hike Leaders Part 4 - Hike Submission Procedures Part 5 – On-line Hike Entry Instructions (AMC Database) Part 5a – Meetup Posting Instructions Part 6 – Accident & Summary of Use Report Overview Part 7 - AMC Incident Report Form Part 8 - WMNF Use Report Form Part 9 - Excursions Committee Meetings Part 10 - Mentor Program Overview Part 11 – Leader Candidate Requirements Part 12 - Mentor Requirements Part 13 - Mentor Evaluation Form Part 14 - Class 1 & 2 Peaks List Part 15 - Class 3 Peaks List Part 16 - Liability Release Form Instructions Part 17 - Release Form FAQs Part 18 - Release Form Part 19 - Activity Finance Policy Part 20 - Yahoo Group Part 21 – Leadership Recognition Part 22 – Crosswalk between Classes and Committees NH AMC Excursion Committee Bylaws Page 1 of 2 AMC-NH Hike Leader Handbook Page 3 of 75. Page 2 of 2 AMC-NH Hike Leader Handbook Page 4 of 75. Hello, Leadership Class Graduate! We hope that you enjoyed yourself at the workshop, and found the weekend worthwhile. We also hope that you will consider becoming a NH Chapter AMC Hike leader—you’ll be a welcome addition to our roster of leaders, and will have a fun and rewarding experience to boot! About the Excursions Committee: We are the hikers in the New Hampshire Chapter, and we also lead some cycling hikes. -

New Hampshirestate Parks M New Hampshire State Parks M

New Hampshire State Parks Map Parks State State Parks State Magic of NH Experience theExperience nhstateparks.org nhstateparks.org Experience theExperience Magic of NH State Parks State State Parks Map Parks State New Hampshire nhstateparks.org A Mountain Great North Woods Region 19. Franconia Notch State Park 35. Governor Wentworth 50. Hannah Duston Memorial of 9 Franconia Notch Parkway, Franconia Historic Site Historic Site 1. Androscoggin Wayside Possibilities 823-8800 Rich in history and natural wonders; 56 Wentworth Farm Rd, Wolfeboro 271-3556 298 US Route 4 West, Boscawen 271-3556 The timeless and dramatic beauty of the 1607 Berlin Rd, Errol 538-6707 home of Cannon Mountain Aerial Tramway, Explore a pre-Revolutionary Northern Memorial commemorating the escape of Presidential Range and the Northeast’s highest Relax and picnic along the Androscoggin River Flume Gorge, and Old Man of the Mountain plantation. Hannah Duston, captured in 1697 during peak is yours to enjoy! Drive your own car or take a within Thirteen Mile Woods. Profile Plaza. the French & Indian War. comfortable, two-hour guided tour on the 36. Madison Boulder Natural Area , which includes an hour Mt. Washington Auto Road 2. Beaver Brook Falls Wayside 20. Lake Tarleton State Park 473 Boulder Rd, Madison 227-8745 51. Northwood Meadows State Park to explore the summit buildings and environment. 432 Route 145, Colebrook 538-6707 949 Route 25C, Piermont 227-8745 One of the largest glacial erratics in the world; Best of all, your entertaining guide will share the A hidden scenic gem with a beautiful waterfall Undeveloped park with beautiful views a National Natural Landmark. -

THE BROWN BULLETIN Er Stating Reason, on FORM 3547, Postage for Which Is Guaranteed

U. 3. Postage PAID BERLIN, N. H. Permit No. 227 POSTMASTER: If undeliverable FOR ANY REASON notify send- THE BROWN BULLETIN er stating reason, on FORM 3547, postage for which is guaranteed. Published By And For The Employees Of Brown Company Brown Company, Berlin, N. EL Volume BERLIN, NEW HAMPSHIRE, JULY 11, 1950 Number 12 New Insurance Benefits New Contract Provides Wage Available To Employees On July 1, 1950 the new schedule of insurance rates Increase - Three Weeks Norman McRae's and benefits became effective Death Felt By and the old plan was termin- ated. The Company has ar- Many Friends ranged for this increase in Vacation - More Holidays Norman L. McRae, an em- benefits with the Company Results Fruitful ployee of Brown Company carrying a major share of the nr urii D -l since January of 1925, died added premium and the em- Berlin Mills Railway In Many Ways Wednesday, June 28th, fol- ployee contributing an addi- tional 20 cents per month for A new contract was approv- lowing a long period of fail- Buys Forty New Steel Cars ed at a general meeting of ing health. Mr. McRae was the added insurance. With the increased personal benefits, the Union recently after the born in Chatham, New Bruns- favorable completion of dis- wick in 1884 and moved to rates paid by the employee have changed from 40 cents cussions between Brown Com- Berlin, N. H. at the age of 36 pany and Local Union No. 75 to work for Brown Company. to 60 cents per month and de- ductions are being made as of the International Brother- His first work for the com- usual. -

Regional Issues

Regional Issues Without a doubt, Berlin has the most stunning location of any community its size in New Hampshire, if not in New England and beyond. The Androscoggin River courses through it, plunging dramatically over a series of falls that were the original source of Berlin’s economic pre-eminence. The Northern Presidentials soar above the community. On a clear day, the 6288’ summit of Mount Washington, New England’s tallest peak, is clearly visible from most parts of the city. Since the closing of the paper mill in nearby Groveton in 2005 and the closing of the pulp mill in Berlin in 2006, a number of demographic, economic development, and marketing efforts have been undertaken focused on Coos County. There is a higher level of cooperation across the county now than many people have seen in years. It is critical for the county that this cooperation continues. As the largest community in the county, it is probably most critical for Berlin that this spirit continues, and that the observations, recommendations, and initiatives are followed through on. As studies are completed, as implementation efforts are considered, there is occasionally a tendency to focus on the details, to lose track of the comprehensive and cohesive view that was intended. Because the success of these regional efforts is so important to Berlin, their major conclusions are summarized here, so that there is one location where all of those initiatives may be viewed collectively, so that as it views its own implementation efforts, the City can readily review the accompanying recommendations to see that those items are being worked on as well. -

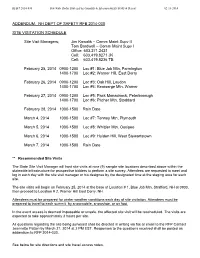

State of New Hampshire

RFB # 2014-030 Statewide Radio System Functionality & Interoperability Study & Report 02-10-2014 ADDENDUM. NH DEPT OF SAFETY RFB 2014-030 SITE VISITATION SCHEDULE Site Visit Managers; Jim Kowalik – Comm Maint Supv II Tom Bardwell – Comm Maint Supv I Office: 603.271.2421 Cell: 603.419.8271 JK Cell: 603.419.8236 TB February 25, 2014 0900-1200 Loc #1: Blue Job Mtn, Farmington 1400-1700 Loc #2: Warner Hill, East Derry February 26, 2014 0900-1200 Loc #3: Oak Hill, Loudon 1400-1700 Loc #4: Kearsarge Mtn, Warner February 27, 2014 0900-1200 Loc #5: Pack Monadnock, Peterborough 1400-1700 Loc #6: Pitcher Mtn, Stoddard February 28, 2014 1000-1500 Rain Date March 4, 2014 1000-1500 Loc #7: Tenney Mtn, Plymouth March 5, 2014 1000-1500 Loc #8: Whittier Mtn, Ossipee March 6, 2014 1000-1500 Loc #9: Holden Hill, West Stewartstown March 7, 2014 1000-1500 Rain Date ** Recommended Site Visits The State Site Visit Manager will host site visits at nine (9) sample site locations described above within the statewide infrastructure for prospective bidders to perform a site survey. Attendees are requested to meet and log in each day with the site visit manager or his designee by the designated time at the staging area for each site. The site visits will begin on February 25, 2014 at the base of Location # 1, Blue Job Mtn, Strafford, NH at 0900, then proceed to Location # 2, Warner Hill East Derry, NH. Attendees must be prepared for winter weather conditions each day of site visitation. Attendees must be prepared to travel to each summit by snowmobile, snowshoe, or on foot. -

December 15, 2020, Volume 18, Number 12 Member Spotlight

MassLand E-News The Newsletter of the Massachusetts Land Conservation Community December 15, 2020, Volume 18, Number 12 Member Spotlight Saving an Iconic Landscape North County Land Trust has a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to protect 200 acres including the south peak of Mt. Watatic. Mt. Watatic is a 1,832-foot monadnock just south of the Massachusetts– New Hampshire border, at the southern end of the Wapack Range of mountains. It lies within Ashburnham and Ashby, in Massachusetts, and New Ipswich in New Hampshire. It’s the terminus for the 22-mile Wapack Trail (heading north into NH) and the 92-mile Midstate Trail (heading south to CT). This parcel is part of a quilt of iconic landscapes and provides a critical addition to an unfragmented block of natural habitat. It would complete preservation of the entire summit of the popular Mt. Watatic. NCLT is working in partnership with the Department Fish and Game, as this property has been on the region’s radar as a key property of conservation interest for decades due to its high conservation and recreational value. Learn more. Or contact NCLT with questions at [email protected] or 978-466-3900. Here's your opportunity to highlight a project in the works, or a current conservation success story! Send a short description and a photo to [email protected]. We'd like to highlight properties in various parts of the state, so if we don't get to you this month, we will soon. If you'd like to support MLTC's efforts to educate, connect, and advocate for the Massachusetts land conservation community, please consider making a monthly or one-time tax-deductible donation Thank you! Donate MassLand News What a pleasure to join Groundwork Lawrence in November for a tour of the Ferrous Site, a beautiful 7.5 acre woodland and meadow created on post-industrial land at the historic and scenic confluence of Lawrence's North Canal and the Spicket and Merrimack Rivers. -

2021-22 LRTA M&G Guideside Final Lo-Res (5-27-21).Indd

www.lakesregion.org 800-60-LAKES www.lakesregion.org 800-60-LAKES MEREDITH BAY ROBERT KOZLOW ROBERT n n n n n n EVP MARKETING and more than 260 other beautiful lakes & ponds! & lakes beautiful other 260 than more and PURITY SPRING RESORT SPRING PURITY Kezar Lake Lake Kezar Lake Highland Ossipee Lake Lake Ossipee n n Lake Winnisquam Lake Opechee Lake Newfound Lake Lake Newfound n n Squam Lake Lake Squam Lake Sunapee Lake Lake Winnipesaukee Winnipesaukee Lake n n WILL BE BE WILL VACATION VACATION LRTA FREE! FREE! OMOT New Hampshire New New Hampshire New of of LAKES REGION LAKES REGION LAKES Map & Guide & Map Guide & Map O F F I C I A L A I C I F F O L A I C I F F O OMOT NHBM Marinas & Boat Rentals E-3 Vacation Home Rentals OTHER EVENTS Popular Hikes for E-4 Families of all Ages E-4 Country Inns G-4 D-3 Shopping E-3 Attractions D-3 D-3 Lake House at E-3 Ferry Point B&B G-6 Healthcare D-3 E-2 E-3 E-4 E-4 Lakes Region Tour Dining E-3 F-3 Spas E-4, E-3, E-3 D-2 State Parks and Swimming Areas D-3 D-4 E-4 E-3 Camping E-2 B-2 n HOLIDAY ACTIVITIES Hotels and Resorts n D-3 Annual Events Christmas at the Castle E-4 Accommodations n n Cabins, Cottages, Golf n Condos and Motels BOAT SHOWS n The Gift of Lights n C-4 E-3 n C-3 E-4 And almost 300 Candlelight Christmas Tours at crystal clear lakes and ponds! ARTS & CRAFTS FAIRS and FESTIVALS Canterbury Shaker Village E-4 C-4 G-3 D-2 C-2 C-2 C-2 D-2 G-3 E-4 C-4 FESTIVALS and FAIRS CRAFTS & ARTS Canterbury Shaker Village Village Shaker Canterbury crystal clear lakes and ponds! and lakes clear crystal Candlelight -

New Hampshire

Town of Jaffrey New Hampshire Annual Report 2013 Dedicated To Maria ChamberlainDedicated to Maria Chamberlain Town Clerk, Jaffrey New Hampshire -‐ 1987 2013 Town Clerk, Jaffrey, New Hampshire 1987 - 2013 “Too often we underestimate the power of a touch, a smile, kind word, a listening “Too ear, often we an underestimate honest the power compliment, of a touch, a smile, a kind or word, the smallest act of caring, all of which a listening have ear, an honest the compliment, potential rn to tu or a the smallest life act of around.” ― caring,Leo Buscaglia all of which have the potential to turn a life around.” As our Town Clerk you made a — Leo difference BuscagliaWe every day. wish you the very best. As our Town Clerk you made a difference every day. We wish you the very best. 2 Town of Jaffrey Table of Contents DIRECTORY OF TOWN OFFICIALS .............................................................................................................. 3 2013 Town Meeting Minutes ...................................................................................................................... 11 2014 Warrant .............................................................................................................................................. 23 Layman’s Warrant....................................................................................................................................... 31 2014 Budget ..............................................................................................................................................