Securitization in Yemen, 2000-2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stand Alone End of Year Report Final

Shelter Cluster Yemen ShelterCluster.org 2019 Coordinating Humanitarian Shelter SHELTER CLUSTER End Year Report Shelter Cluster Yemen Foreword Yemeni people continue to show incredible aspirations and the local real estate market and resilience after ve years of conict, recurrent ood- environmental conditions: from rental subsidies ing, constant threats of famine and cholera, through cash in particular to prevent evictions extreme hardship to access basic services like threats to emergency shelter kits at the onset of a education or health and dwindling livelihoods displacement, or winterization upgrading of opportunities– and now, COVID-19. Nearly four shelters of those living in mountainous areas of million people have now been displaced through- Yemen or in sites prone to ooding. Both displaced out the country and have thus lost their home. and host communities contributed to the design Shelter is a vital survival mechanism for those who and building of shelters adapted to the Yemeni have been directly impacted by the conict and context, resorting to locally produced material and had their houses destroyed or have had to ee to oering a much-needed cash-for-work opportuni- protect their lives. Often overlooked, shelter inter- ties. As a result, more than 2.1 million people bene- ventions provide a safe space where families can tted from shelter and non-food items interven- pause and start rebuilding their lives – protected tions in 2019. from the elements and with the privacy they are This report provides an overview of 2019 key entitled to. Shelters are a rst step towards achievements through a series of maps and displaced families regaining their dignity and build- infographics disaggregated by types of interven- ing their self-reliance. -

Yemen's National Dialogue

arab uprisings Yemen’s National Dialogue March 21, 2013 MOHAMMED HUWAIS/AFP/GETTY IMAGES HUWAIS/AFP/GETTY MOHAMMED POMEPS Briefings 19 Contents Overcoming the Pitfalls of Yemen’s National Dialogue . 5 Consolidating Uncertainty in Yemen . 7 Can Yemen be a Nation United? . 10 Yemen’s Southern Intifada . 13 Best Friends Forever for Yemen’s Revolutionaries? . 18 A Shake Up in Yemen’s GPC? . 21 Hot Pants: A Visit to Ousted Yemeni Leader Ali Abdullah Saleh’s New Presidential Museum . .. 23 Triage for a fracturing Yemen . 26 Building a Yemeni state while losing a nation . 32 Yemen’s Rocky Roadmap . 35 Don’t call Yemen a “failed state” . 38 The Project on Middle East Political Science The Project on Middle East Political Science (POMEPS) is a collaborative network which aims to increase the impact of political scientists specializing in the study of the Middle East in the public sphere and in the academic community . POMEPS, directed by Marc Lynch, is based at the Institute for Middle East Studies at the George Washington University and is supported by the Carnegie Corporation and the Social Science Research Council . It is a co-sponsor of the Middle East Channel (http://mideast .foreignpolicy .com) . For more information, see http://www .pomeps .org . Online Article Index Overcoming the Pitfalls of Yemen’s National Dialogue http://mideast .foreignpolicy .com/posts/2013/03/18/overcoming_the_pitfalls_of_yemen_s_national_dialogue Consolidating Uncertainty in Yemen http://mideast .foreignpolicy .com/posts/2013/02/22/consolidating_uncertainty_in_yemen -

06.22.12-USAID-DCHA Yemen Complex Emergency

FACT SHEET #9, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2012 JUNE 22, 2012 YEMEN – COMPLEX EMERGENCY KEY DEVELOPMENTS From June 19 to 21, USAID Administrator Rajiv Shah traveled to Yemen to discuss humanitarian and development issues in the country with high-level representatives from the Republic of Yemen Government (RoYG)—including President Abdrabuh Mansur Hadi and Foreign Minister Abu Bakr al-Qirbi—and members of the international humanitarian and development communities. During the visit, Administrator Shah announced plans to provide up to $52 million in additional U.S. Government (USG) assistance to Yemen, including approximately $23 million in humanitarian assistance. Administrator Shah’s announcement brings total USG humanitarian and development assistance in FY 2012 to approximately $170 million, including nearly $105 million in humanitarian assistance. The additional humanitarian assistance will help address the humanitarian needs of conflict-affected populations across Yemen through the distribution of emergency relief supplies and food assistance, as well as support for nutrition and water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) interventions. Prior to Administrator Shah’s visit, Nancy Lindborg, Assistant Administrator for USAID’s Bureau for Democracy, Conflict, and Humanitarian Assistance (AA/DCHA), traveled to Yemen’s capital city of Sana’a from June 1 to 3 to discuss humanitarian issues with the RoYG, U.S. Embassy in Sana’a, USAID/Yemen, and international humanitarian community representatives. During her visit, AA/DCHA Lindborg announced an additional $6.5 million in humanitarian assistance to Yemen to address the needs of vulnerable and conflict-affected populations in the country. On May 12, RoYG forces launched an offensive aimed at reclaiming towns and cities controlled by militant groups in Abyan Governorate. -

Security Council Distr.: General 27 January 2020

United Nations S/2020/70 Security Council Distr.: General 27 January 2020 Original: English Letter dated 27 January 2020 from the Panel of Experts on Yemen addressed to the President of the Security Council The members of the Panel of Experts on Yemen have the honour to transmit herewith the final report of the Panel, prepared in accordance with paragraph 6 of resolution 2456 (2019). The report was provided to the Security Council Committee established pursuant to resolution 2140 (2014) on 27 December 2019 and was considered by the Committee on 10 January 2020. We would appreciate it if the present letter and the report were brought to the attention of the members of the Security Council and issued as a document of the Council. (Signed) Dakshinie Ruwanthika Gunaratne Coordinator Panel of Experts on Yemen (Signed) Ahmed Himmiche Expert (Signed) Henry Thompson Expert (Signed) Marie-Louise Tougas Expert (Signed) Wolf-Christian Paes Expert 19-22391 (E) 070220 *1922391* S/2020/70 Final report of the Panel of Experts on Yemen Summary After more than five years of conflict, the humanitarian crisis in Yemen continues. The country’s many conflicts are interconnected and can no longer be separated by clear divisions between external and internal actors and events. Throughout 2019, the Houthis and the Government of Yemen made little headway towards either a political settlement or a conclusive military victory. In a continuation from 2018, the belligerents continued to practice economic warfare: using economic obstruction and financial tools as weapons to starve opponents of funds or materials. Profiteering from the conflict is endemic. -

Yemen and The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by LSE Research Online Kuwait Programme on Development, Governance and Globalisation in the Gulf States ‘One blood and one destiny’? Yemen’s relations with the Gulf Cooperation Council Edward Burke June 2012 Number 23 The Kuwait Programme on Development, Governance and Globalisation in the Gulf States is a ten-year multidisciplinary global research programme. It focuses on topics such as globalization and the repositioning of the Gulf States in the global order, capital flows, and patterns of trade; specific challenges facing carbon-rich and resource-rich economic development; diversification, educational and human capital development into post-oil political economies; and the future of regional security structures in the post-Arab Spring environment. The Programme is based in the LSE Department of Government and led by Professor Danny Quah and Dr Kristian Ulrichsen. The Programme produces an acclaimed working paper series featuring cutting-edge original research on the Gulf, published an edited volume of essays in 2011, supports post-doctoral researchers and PhD students, and develops academic networks between LSE and Gulf institutions. At the LSE, the Programme organizes a monthly seminar series, invitational breakfast briefings, and occasional public lectures, and is committed to five major biennial international conferences. The first two conferences took place in Kuwait City in 2009 and 2011, on the themes of Globalization and the Gulf, and The Economic Transformation of the Gulf. The next conference will take place at the LSE in March 2013, on the theme of The Arab Spring and the Gulf: Politics, Economics, and Security. -

The War in Yemen: 2011-2018: the Elusive Road to Peace

Working Paper 18-1 By Sonal Marwah and Tom Clark The War in Yemen: 2011-2018 The elusive road to peace November 2018 The War in Yemen: 2011-2018 The elusive road to peace By Sonal Marwah and Tom Clark Working Paper 18-1 Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publications Data The War in Yemen: 2011-2018: The elusive road to peace ISBN 978-1-927802-24-3 © 2018 Project Ploughshares First published November 2018 Please direct enquires to: Project Ploughshares 140 Westmount Road North Waterloo, Ontario N2L 3G6 Canada Telephone: 519-888-6541 Email: [email protected] Editing: Wendy Stocker Design and layout: Tasneem Jamal Table of Contents Glossary of Terms i List of Figures ii Acronyms and Abbreviations iii Acknowledgements v Executive Summary 1 Introduction 2 Background 4 Participants in the Conflict 6 Major local actors 6 Foreign and regional actors 7 Major arms suppliers 7 Summary of the Conflict (2011-2018) 8 Civil strife breaks out (January 2011 to March 2015) 8 The internationalization of conflict (2015) 10 An influx of weapons and more human-rights abuses (2016) 10 A humanitarian catastrophe (2017- June 2018) 13 The Scale of the Forgotten War 16 Battle-related deaths 17 Forcibly displaced persons 17 Conflict and food insecurity 22 Infrastructural collapse 23 Arming Saudi Arabia 24 Prospects for Peace 26 Regulation of Arms Exports 30 The Path Ahead and the UN 32 Conclusion 33 Authors 34 Endnotes 35 Photo Credits 41 Glossary of Terms Arms Trade Treaty: A multilateral treaty, which entered into force in December 2014, that establishes -

Conflict in Yemen

conflict in yemen abyan’s DarkEst hour amnesty international is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the universal declaration of human rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. first published in 2012 by amnesty international ltd Peter benenson house 1 easton street london Wc1X 0dW united kingdom © amnesty international 2012 index: mde 31/010/2012 english original language: english Printed by amnesty international, international secretariat, united kingdom all rights reserved. this publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. the copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. for copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. to request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover phot o: a building in Zinjibar destroyed during the fighting, July 2012. © amnesty international amnesty.org CONFLICT IN YEMEN: ABYAN’S DARKEST HOUR CONTENTS Contents ......................................................................................................................1 -

USG Yemen Complex Emergency Program

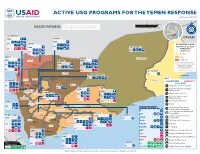

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS FOR THE YEMEN RESPONSE Last Updated 02/12/20 0 50 100 mi INFORMA Partner activities are contingent upon access to IC TI PH O A N R U G SAUDI ARABIA conict-aected areas and security concerns. 0 50 100 150 km N O I T E G U S A A D ID F /DCHA/O AL HUDAYDAH IOM AMRAN OMAN IOM IPs SA’DAH ESTIMATED FOOD IPs SECURITY LEVELS IOM HADRAMAWT IPs THROUGH IPs MAY 2020 IPs Stressed HAJJAH Crisis SANA’A Hadramawt IOM Sa'dah AL JAWF IOM Emergency An “!” indicates that the phase IOM classification would likely be worse IPs Sa'dah IPs without current or planned IPs humanitarian assistance. IPs Source: FEWS NET Yemen IPs AL MAHRAH Outlook, 02/20 - 05/20 Al Jawf IP AMANAT AL ASIMAH Al Ghaedha IPs KEY Hajjah Amran Al Hazem AL MAHWIT Al Mahrah USAID/OFDA USAID/FFP State/PRM Marib IPs Hajjah Amran MARIB Agriculture and Food Security SHABWAH IPs IBB Camp Coordination and Camp Al Mahwit IOM IPs Sana'a Management Al Mahwit IOM DHAMAR Sana'a IPs Cash Transfers for Food Al IPs IPs Economic Recovery and Market Systems Hudaydah IPs IPs Food Voucher Program RAYMAH IPs Dhamar Health Raymah Al Mukalla IPs Shabwah Ataq Dhamar COUNTRYWIDE Humanitarian Coordination Al Bayda’ and Information Management IP Local, Regional, and International Ibb AD DALI’ Procurement TA’IZZ Al Bayda’ IOM Ibb ABYAN IOM Al BAYDA’ Logistics Support and Relief Ad Dali' OCHA Commodities IOM IOM IP Ta’izz Ad Dali’ Abyan IPs WHO Multipurpose Cash Assistance Ta’izz IPs IPs UNHAS Nutrition Lahij IPs LAHIJ Zinjubar UNICEF Protection IPs IPs WFP Ready-to-Use Therapeutic Food IOM Al-Houta ADEN FAO Refugee and Migrant Assistance IPs Aden IOM UNICEF Risk Management Policy and Practice Shelter and Settlements IPs WFP SOCOTRA DJIBOUTI, ETHIOPIA, U.S. -

Yemen on the Verge of Total State Collapse While the Global Community Remains Silent

Charlotte Hohmann / Said AlDailami Yemen on the Verge of Total State Collapse While the Global Community Remains Silent Six years after the successful protests of the so-called “Arab Spring” leading to the resignation of former President Ali Abdallah Saleh, Yemen is facing a war on multip- le fronts. The Arab world’s poorest country is suffering from a political situation that has already been fragile and is now on the verge of total state collapse. The violence has triggered a humanitarian disaster with at least three million Yemenis being in- ternally displaced and a famine threatening the country. An end of the conflict is not yet in sight. The international community seems to follow their own interests instead of trying to conclude a ceasefire and peace agreement. Schlagwörter: Arab Spring - Yemen - Civil War - Sunni-Shia - Conflict Saudi Arabia-Iran - Houthi - Saleh - International Intervention YEMEN ON THE VERGE OF TOTAL STATE COLLAPSE WHILE THE GLOBAL COMMUNITY REMAINS SILENT || Charlotte Hohmann / Sail AlDailami Introductory Remarks Generally speaking, Yemen is now divided between two warring parties. Six years after the start of the 2011 The country has been devastated by a uprising and the successful protests of struggle between forces loyal to the in- the so-called “Arab Spring”, leading to ternationally recognized government the resignation of former President Ali under president Hadi and those allied to Abdallah Saleh, Yemen is facing a war on the Houthi rebel movement. Since March multiple fronts. The combination of 2015 at least 10,000 civilians have been proxy wars, sectarian violence, state killed and 42,000 injured2 – the majority collapse and militia rule has sadly be- due to air strikes effected by a Saudi-led come part of the everyday routine. -

Political Instability in Yemen (1962- 2014)

T.C. ANKARA YILDIRIM BEYAZIT UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCE POLITICAL INSTABILITY IN YEMEN (1962- 2014) MASTER’S THESIS Sohaib Abdulhameed Abdulsalam SHAMSAN DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE AND PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION ANKARA, 2020 T.C. ANKARA YILDIRIM BEYAZIT UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES POLITICAL INSTABILITY IN YEMEN (1962- 2014) MASTER’S THESIS Sohaib Abdulhameed Abdulsalam SHAMSAN DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE AND PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION Prof. Dr. Yılmaz BINGÖL ANKARA 2020 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences __________________________ Assoc. Prof. Dr. Seyfullah YILDIRIM Manager of Institute of Social Science I certify that this thesis satisfies the entire requirement as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in Political Science and Public Administration. ___________________________ Prof. Dr. Yılmaz Bingöl Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. ___________________________ Prof. Dr. Yılmaz Bingöl Supervisor Examining Committee Members: 1. Prof. Dr. Yılmaz BİNGÖL AYBU, PSPA ________________________ 2. Assist. Prof. Dr Güliz Dinç. AYBU, PSPA ________________________ 3. Prof. Dr. Murat ÖNDER ASBÜ ________________________ DECLARATION I hereby declare that all information in this document obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Sohaib Abdulhameed Abdulsalam SHAMSAN ___________________________ ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First, I wish to show my gratitude to, and express my sincere appreciation to my supervisor, Professor Dr. -

Struggle for Citizenship.Indd

From the struggle for citizenship to the fragmentation of justice Yemen from 1990 to 2013 Erwin van Veen CRU Report From the struggle for citizenship to the fragmentation of justice FROM THE STRUGGLE FOR CITIZENSHIP TO THE FRAGMENTATION OF JUSTICE Yemen from 1990 to 2013 Erwin van Veen Conflict Research Unit, The Clingendael Institute February 2014 © Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright holders. Clingendael Institute P.O. Box 93080 2509 AB The Hague The Netherlands Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.clingendael.nl/ Table of Contents Executive summary 7 Acknowledgements 11 Abbreviations 13 1 Introduction 14 2 Selective centralisation of the state: Commerce and security through networked rule 16 Enablers: Tribes, remittances, oil and civil war 17 Tools: Violence, business and religion 21 The year 2011 and the National Dialogue Conference 26 The state of justice in 1990 and 2013 28 3 Trend 1: The ‘instrumentalisation’ of state-based justice 31 Key strategies in the instrumentalisation of justice 33 Consequences of politicisation and instrumentalisation 34 4 Trend 2: The weakening of tribal customary law 38 Functions and characteristics of tribal law 40 Key factors that have weakened tribal law 42 Consequences of weakened tribal law 44 Points of connection -

A New Model for Defeating Al Qaeda in Yemen

A New Model for Defeating al Qaeda in Yemen Katherine Zimmerman September 2015 A New Model for Defeating al Qaeda in Yemen KATHERINE ZIMMERMAN SEPTEMBER 2015 A REPORT BY AEI’S CRITICAL THREATS PROJECT TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Part I: Al Qaeda and the Situation in Yemen ................................................................................................. 5 A Broken Model in Yemen ...................................................................................................................... 5 The Collapse of America’s Counterterrorism Partnership ........................................................................ 6 The Military Situation in Yemen ........................................................................................................... 10 Yemen, Iran, and Regional Dynamics ................................................................................................... 15 The Expansion of AQAP and the Emergence of ISIS in Yemen ............................................................ 18 Part II: A New Strategy for Yemen ............................................................................................................. 29 Defeating the Enemy in Yemen ............................................................................................................