Updated March 2015 (Replaces February 2010 Version)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1PM in Oregon

(-ia Does not circulate Special Report 1020 October 2000 k 1PMin Oregon: Achievements and Future Directions N EMATOLOGY 4 ENTOMOLOGY 'V SOCIAL SCIEESI Integrated plant protection center OREGONSTATE UNIVERSITY I EXTENSION SERVICE For additional copies of this publication, send $15.00per copy to: Integrated Plant Protection Center 2040 Cordley Hall Oregon State University Corvallis, OR 9733 1-3904 Oregon State University Extension Service SpecialReport 1020 October 2000 1PMin Oregon: Achievements and Future Directions Editors: Myron Shenk Integrated Pest Management Specialist and Marcos Kogan Director, Integrated Plant Protection Center Oregon State University Table of Contents Welcome I Introductions 1 Marcos Kogan, OSU, Director IPPC Words from the President of Oregon State University 3 Paul Risser, President of OSU OSU Extension Service's Commitment to 1PM 5 Lyla Houglum, OSU, Director OSU-ES 1PM on the National Scene 8 Harold Coble, N. Carolina State U.! NatI. 1PM Program Coordinator The Role of Extension in Promoting 1PM Programs 13 Michael Gray, University of Illinois, 1PM Coordinator Performance Criteria for Measuring 1PM Results 19 Charles Benbrook, Benbrook Consulting Services FQPA Effects on Integrated Pest Management in the United States 28 Mark Whalon, Michigan State University and Resistance Management 1PM: Grower Friendly Practices and Cherry Grower Challenges 34 Bob Bailey, Grower, The Dalles Areawide Management of Codling Moth in Pears 36 Philip Vanbuskirk, Richard Hilton, Laura Naumes, and Peter Westigard, OSU Extension Service, Jackson County; Naumes Orchards, Medford Integrated Fruit Production for Pome Fruit in Hood River: Pest Management in the Integrated Fruit Production (IFP) Program 43 Helmut Riedl, Franz Niederholzer, and Clark Seavert, OSU Mid-Columbia Research and Ext. -

Montreal Protocol on Substances That Deplete the Ozone Layer

MONTREAL PROTOCOL ON SUBSTANCES THAT DEPLETE THE OZONE LAYER 1994 Report of the Methyl Bromide Technical Options Committee 1995 Assessment UNEP 1994 Report of the Methyl Bromide Technical Options Committee 1995 Assessment Montreal Protocol On Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer UNEP 1994 Report of the Methyl Bromide Technical Options Committee 1995 Assessment The text of this report is composed in Times Roman. Co-ordination: Jonathan Banks (Chair MBTOC) Composition and layout: Michelle Horan Reprinting: UNEP Nairobi, Ozone Secretariat Date: 30 November 1994 No copyright involved. Printed in Kenya; 1994. ISBN 92-807-1448-1 1994 Report of the Methyl Bromide Technical Options Committee for the 1995 Assessment of the MONTREAL PROTOCOL ON SUBSTANCES THAT DEPLETE THE OZONE LAYER pursuant to Article 6 of the Montreal Protocol; Decision IV/13 (1993) by the Parties to the Montreal Protocol Disclaimer The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the Technology and Economics Assessment Panel co-chairs and members, the Technical and Economics Options Committees chairs and members and the companies and organisations that employ them do not endorse the performance, worker safety, or environmental acceptability of any of the technical options discussed. Every industrial operation requires consideration of worker safety and proper disposal of contaminants and waste products. Moreover, as work continues - including additional toxicity testing and evaluation - more information on health, environmental and safety effects of alternatives and replacements -

Vernal Pool Tadpole Shrimp (Lepidurus Packardi)

Vernal Pool Tadpole Shrimp (Lepidurus packardi) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Sacramento Fish and Wildlife Office Sacramento, California September 2007 5-YEAR REVIEW Vernal pool tadpole shrimp (Lepidurus packardi) I. GENERAL INFORMATION I.A. Methodology used to complete the review: This review was prepared by the Sacramento Fish and Wildlife Office (SFWO) of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) using information from the 2005 Recovery Plan for Vernal Pool Ecosystems of California and Southern Oregon (Recovery Plan) (Service 2005a), species survey and monitoring reports, peer-reviewed journal articles, documents generated as part of Endangered Species Act (Act) section 7 consultations and section 10 coordination, Federal Register notices, the California Natural Diversity Database (CNDDB) maintained by the California Department of Fish and Game (CDFG), and species experts who have been monitoring various occurrences of this species. We also considered information from a Service- contracted report. The Recovery Plan and personal communications with experts were our primary sources of information used to update the “species status” and “threats” sections of this review. I.B. Contacts Lead Regional or Headquarters Office – Diane Elam, Deputy Division Chief for Listing, Recovery, and Habitat Conservation Planning, and Jenness McBride, Fish and Wildlife Biologist, California/Nevada Operations Office, 916-414-6464 Lead Field Office – Kirsten Tarp, Recovery Branch, Sacramento Fish and Wildlife Office, 916- 414-6600 I.C. Background I.C.1. FR Notice citation announcing initiation of this review: 71 FR 14538, March 22, 2006. This notice requested information from the public; we received no information in response to the notice. -

Risk Analysis of Alien Grasses Occurring in South Africa

Risk analysis of alien grasses occurring in South Africa By NKUNA Khensani Vulani Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science at Stellenbosch University (Department of Botany and Zoology) Supervisor: Dr. Sabrina Kumschick Co-supervisor (s): Dr. Vernon Visser : Prof. John R. Wilson Department of Botany & Zoology Faculty of Science Stellenbosch University December 2018 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis/dissertation electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: December 2018 Copyright © 2018 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved i Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract Alien grasses have caused major impacts in their introduced ranges, including transforming natural ecosystems and reducing agricultural yields. This is clearly of concern for South Africa. However, alien grass impacts in South Africa are largely unknown. This makes prioritising them for management difficult. In this thesis, I investigated the negative environmental and socio-economic impacts of 58 alien grasses occurring in South Africa from 352 published literature sources, the mechanisms through which they cause impacts, and the magnitudes of those impacts across different habitats and regions. Through this assessment, I ranked alien grasses based on their maximum recorded impact. Cortaderia sellonoana had the highest overall impact score, followed by Arundo donax, Avena fatua, Elymus repens, and Festuca arundinacea. -

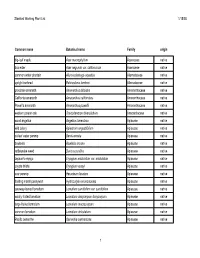

Plant List for Web Page

Stanford Working Plant List 1/15/08 Common name Botanical name Family origin big-leaf maple Acer macrophyllum Aceraceae native box elder Acer negundo var. californicum Aceraceae native common water plantain Alisma plantago-aquatica Alismataceae native upright burhead Echinodorus berteroi Alismataceae native prostrate amaranth Amaranthus blitoides Amaranthaceae native California amaranth Amaranthus californicus Amaranthaceae native Powell's amaranth Amaranthus powellii Amaranthaceae native western poison oak Toxicodendron diversilobum Anacardiaceae native wood angelica Angelica tomentosa Apiaceae native wild celery Apiastrum angustifolium Apiaceae native cutleaf water parsnip Berula erecta Apiaceae native bowlesia Bowlesia incana Apiaceae native rattlesnake weed Daucus pusillus Apiaceae native Jepson's eryngo Eryngium aristulatum var. aristulatum Apiaceae native coyote thistle Eryngium vaseyi Apiaceae native cow parsnip Heracleum lanatum Apiaceae native floating marsh pennywort Hydrocotyle ranunculoides Apiaceae native caraway-leaved lomatium Lomatium caruifolium var. caruifolium Apiaceae native woolly-fruited lomatium Lomatium dasycarpum dasycarpum Apiaceae native large-fruited lomatium Lomatium macrocarpum Apiaceae native common lomatium Lomatium utriculatum Apiaceae native Pacific oenanthe Oenanthe sarmentosa Apiaceae native 1 Stanford Working Plant List 1/15/08 wood sweet cicely Osmorhiza berteroi Apiaceae native mountain sweet cicely Osmorhiza chilensis Apiaceae native Gairdner's yampah (List 4) Perideridia gairdneri gairdneri Apiaceae -

Oregon Invasive Species Action Plan

Oregon Invasive Species Action Plan June 2005 Martin Nugent, Chair Wildlife Diversity Coordinator Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife PO Box 59 Portland, OR 97207 (503) 872-5260 x5346 FAX: (503) 872-5269 [email protected] Kev Alexanian Dan Hilburn Sam Chan Bill Reynolds Suzanne Cudd Eric Schwamberger Risa Demasi Mark Systma Chris Guntermann Mandy Tu Randy Henry 7/15/05 Table of Contents Chapter 1........................................................................................................................3 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 3 What’s Going On?........................................................................................................................................ 3 Oregon Examples......................................................................................................................................... 5 Goal............................................................................................................................................................... 6 Invasive Species Council................................................................................................................. 6 Statute ........................................................................................................................................................... 6 Functions ..................................................................................................................................................... -

Global Environmental and Socio-Economic Impacts of Selected Alien Grasses As a Basis for Ranking Threats to South Africa

A peer-reviewed open-access journal NeoBiota 41: 19–65Global (2018) environmental and socio-economic impacts of selected alien grasses... 19 doi: 10.3897/neobiota.41.26599 RESEARCH ARTICLE NeoBiota http://neobiota.pensoft.net Advancing research on alien species and biological invasions Global environmental and socio-economic impacts of selected alien grasses as a basis for ranking threats to South Africa Khensani V. Nkuna1,2, Vernon Visser3,4, John R.U. Wilson1,2, Sabrina Kumschick1,2 1 South African National Biodiversity Institute, Kirstenbosch Research Centre, Cape Town, South Africa 2 Centre for Invasion Biology, Department of Botany and Zoology, Stellenbosch University, Matieland, 7602, South Africa 3 SEEC – Statistics in Ecology, Environment and Conservation, Department of Statistical Scien- ces, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch, 7701 South Africa 4 African Climate and Development Initiative, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch, 7701, South Africa Corresponding author: Sabrina Kumschick ([email protected]) Academic editor: C. Daehler | Received 14 May 2018 | Accepted 14 November 2018 | Published 21 December 2018 Citation: Nkuna KV, Visser V, Wilson JRU, Kumschick S (2018) Global environmental and socio-economic impacts of selected alien grasses as a basis for ranking threats to South Africa. NeoBiota 41: 19–65. https://doi.org/10.3897/ neobiota.41.26599 Abstract Decisions to allocate management resources should be underpinned by estimates of the impacts of bio- logical invasions that are comparable across species and locations. For the same reason, it is important to assess what type of impacts are likely to occur where, and if such patterns can be generalised. In this paper, we aim to understand factors shaping patterns in the type and magnitude of impacts of a subset of alien grasses. -

Polypogon Monspeliensis (L.) Desf., 1798, CONABIO, Junio 2016 Polypogon Monspeliensis (L.) Desf., 1798

Método de Evaluación Rápida de Invasividad (MERI) para especies exóticas en México Polypogon monspeliensis (L.) Desf., 1798, CONABIO, Junio 2016 Polypogon monspeliensis (L.) Desf., 1798 Foto: Philipp Weigell, 2013. Fuente: Wikimedia Polypogon monspeliensis es una hierba anual reportada como invasora en varios países (PIER, 2011), al parecer esta especie es huésped del nematodo Anguina sp . el cual es vector de la bacteria Clavibacter toxicus , productor de la corynetoxina causante de la muerte del ganado conocida como toxicidad de ballica anual (ARGT) (Halvorson & Guertin, 2003; McKay et al., 1993), en Estados Unidos P. monspeliensis ha afectado a Orcuttia inaequidens, Orcurttia pilosa y Tuctoria greenei , especies con categoría de riesgo (CABI, 2014). Información taxonómica Reino: Plantae División: Tracheophyta Clase: Magnoliopsida Orden: Poales Familia: Poaceae Género: Polypogon Especie: Polypogon monspeliensis (L.) Desf., 1798 Nombre común: rabo de cordero, rabo de zorra, cola de zorro (Secretaria Distrital de Ambiente, 2009). 1 Método de Evaluación Rápida de Invasividad (MERI) para especies exóticas en México Polypogon monspeliensis (L.) Desf., 1798, CONABIO, Junio 2016 Valor de invasividad: 0.4656 Categoría de riesgo : Alto Descripción de la especie Polypogon monspeliensis es una hierba anual con tallos y hojas envainantes y alternas, lígula membranosa. La Inflorescencia en panícula densa, oblongoidea, sedosa, a veces lobada. Las espiguillas con una flor hermafrodita, pedúnculos articulados en la parte superior, 2 glumas subiguales, mayores que las flores, emarginadas, aristadas, con espículos cónicos en la base. Lemas dentadas, con arista terminal. Con tres estambres (Secretaria Distrital de Ambiente, 2009). se reproduce por semillas que son dispersadas por animales (CABI, 2014; PIER, 2011). Distribución original Originario de Europa, África y Asia. -

Cytogenetic Studies in Some Representatives of the Subfamily Pooideae (Poaceae) in South Africa

Bothalia 26,1: 63-67(1996) Cytogenetic studies in some representatives of the subfamily Pooideae (Poaceae) in South Africa. 2. The tribe Aveneae, subtribes Phalaridinae and Alopecurinae J.J. SPIES*, S.K. SPIES*, S.M.C. VAN WYK*, A.F. MALAN*t and E.J.L. LIEBENBERG** Keywords: Aveneae, chromosomes, meiosis, Poaceae, polyploidy, Pooideae ABSTRACT This is a report on chromosome numbers for the subtribes Phalaridinae and Alopecurinae (tribe Aveneae) which are. to a large extent, naturalized in South Africa. Chromosome numbers of 34 specimens, representing nine species and four genera, are presented. These numbers include the first report on Agrostis avenacea Gmel. (n = 4x = 28). New ploidv levels are reported for Phalaris aquatica L. (n = x = 7), Agrostis barbuligera Stapf var. barbuligera (n = 2x = 14 and n = 4x = 28) and A. lachnantha Nees var. lachnantha (n = 3x = 21). INTRODUCTION terial used and the collecting localities are listed in Table 1. Voucher specimens are housed in the Geo Potts Her The first paper in this series on chromosome num barium, Department of Botany and Genetics, University bers of representatives of the tribe Aveneae in South Af of the Orange Free State, Bloemfontein (BLFU) or the rica, indicated the importance of determining the ploidy National Herbarium, Pretoria (PRE). levels and basic chromosome numbers of naturalized and endemic flora in South Africa (Spies et al. 19%). This Anthers were squashed in aceto-carmine and meioti- second paper in the series is restricted to the subtribes cally analysed (Spies et al. 1996). Chromosome numbers Phalaridinae and Alopecurinae. are presented as haploid chromosome numbers to conform to previous papers on chromosome numbers in this journal The subtribe Phalaridinae Rchb. -

Biology and Control of the Anguinid Nematode

BIOLOGY AND CONTROL OF THE AIIGTIINID NEMATODE ASSOCIATED WITH F'LOOD PLAIN STAGGERS by TERRY B.ERTOZZI (B.Sc. (Hons Zool.), University of Adelaide) Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The University of Adelaide (School of Agriculture and Wine) September 2003 Table of Contents Title Table of contents.... Summary Statement..... Acknowledgments Chapter 1 Introduction ... Chapter 2 Review of Literature 2.I Introduction.. 4 2.2 The 8acterium................ 4 2.2.I Taxonomic status..' 4 2.2.2 The toxins and toxin production.... 6 2.2.3 Symptoms of poisoning................. 7 2.2.4 Association with nematodes .......... 9 2.3 Nematodes of the genus Anguina 10 2.3.1 Taxonomy and sYstematics 10 2.3.2 Life cycle 13 2.4 Management 15 2.4.1 Identifi cation...................'..... 16 2.4.2 Agronomicmethods t6 2.4.3 FungalAntagonists l7 2.4.4 Other strategies 19 2.5 Conclusions 20 Chapter 3 General Methods 3.1 Field sites... 22 3.2 Collection and storage of Polypogon monspeliensis and Agrostis avenaceø seed 23 3.3 Surface sterilisation and germination of seed 23 3.4 Collection and storage of nematode galls .'.'.'.....'.....' 24 3.5 Ext¡action ofjuvenile nematodes from galls 24 3.6 Counting nematodes 24 3.7 Pot experiments............. 24 Chapter 4 Distribution of Flood Plain Staggers 4.1 lntroduction 26 4.2 Materials and Methods..............'.. 27 4.2.1 Survey of Murray River flood plains......... 27 4.2.2 Survey of southeastern South Australia .... 28 4.2.3 Surveys of northern New South Wales...... 28 4.3 Results 29 4.3.1 Survey of Murray River flood plains... -

SFAN Early Detection V1.4

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Program Center Early Detection of Invasive Plant Species in the San Francisco Bay Area Network A Volunteer-Based Approach Natural Resource Report NPS/SFAN/NRR—2009/136 ON THE COVER Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy employee Elizabeth Speith gathers data on an invasive Cotoneaster shrub. Photograph by: Andrea Williams, NPS. Early Detection of Invasive Plant Species in the San Francisco Bay Area Network A Volunteer-Based Approach Natural Resource Report NPS/SFAN/NRR—2009/136 Andrea Williams Marin Municipal Water District Sky Oaks Ranger Station 220 Nellen Avenue Corte Madera, CA 94925 Susan O'Neil Woodland Park Zoo 601 N 59th Seattle, WA 98103 Elizabeth Speith USGS NBII Pacific Basin Information Node Box 196 310 W Kaahumau Avenue Kahului, HI 96732 Jane Rodgers Socio-Cultural Group Lead Grand Canyon National Park PO Box 129 Grand Canyon, AZ 86023 August 2009 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Program Center Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Program Center publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate high-priority, current natural resource management information with managerial application. The series targets a general, diverse audience, and may contain NPS policy considerations or address sensitive issues of management applicability. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. -

Notes on Newly Recorded Grasses in Taiwan

Taiwania, 51(1): 25-31, 2006 Notes on Newly Recorded Grasses in Taiwan Ming-Jer Jung(1), Tian-Shung Wu(2,3) and Chang-Sheng Kuoh(1,4) (Manuscript received 15 August, 2005; accepted 30 September, 2005) ABSTRACT: Agrostis avenacea J. F. Gmel., Agrostis stolonifera L., Alopecurus pratensis L., and Deschampsia atropurpurea (Wahl.) Scheele were recently found at middle elevations of southern and central Taiwan, respectively. We present their descriptions, distribution map, and line-drawings. KEY WORDS: Agrostis avenacea, Agrostis stolonifera, Alopecurus pratensis, Deschampsia atropurpurea, Gramineae, Naturalized grasses, Poaceae, Taiwan, Taxonomy. INTRODUCTION Culms erect, to 1 m tall, 3-5-noded; prostrate at fruiting. Leaf sheath glabrous, ligule ca. 5 mm long, In participation of a long term project, we have membranous, apex acuminate; blades 5-20 cm long. been collecting plant materials in Taiwan for drug Inflorescence a panicle, effuse, asymmetrical, with screening since 2002. We found four species of 2-4 nodes, 12-30 cm long; pedicels 5-10 cm long, grasses new to the flora of Taiwan recently. They are scabrous. Spikelet pedicellate, laterally compressed, two species of Agrostis, one species of Alopecurus, with one floret. Lower glume ca. 3 mm long, and one species of Deschampsia, respectively. The one-veined, scabrous on vein, apex acuminate. genus Agrostis L. consists of ca. 220 species in Upper glume slightly shorter than lower glume, temperate areas and on tropical mountains (Clayton one-veined, scabrous on vein, apex acuminate. and Renvoize, 1986). In Taiwan, Agrostis has been Rachilla ca. 0.3 mm long, hairy; callus bearded. revised by several authors (Hsu, 1978; Veldkamp, Lemma elliptical to ovate, hairy, awn arising from 1982; Kuoh and Chen, 2000), and five taxa were middle, ca.