Iranian Intellectuals and the West, 1960-1990

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2013 3. Szám 2013 Október

Jogelméleti Szemle 20132013////3333.. szám TARTALOM Tanulmányok Bodnár, Zsolt: The interrelationships of segregation and its impact on crime .................................... 2 Frivaldszky János – Frivaldszkyné Jung Csilla: Az öngyilkosság és az abban való közrem űködés a természetes erkölcsi törvény és természetjogi gondolkodás szempontjából ....................................... 7 Hamza Gábor: A magánjog fejl ődése és kodifikációja Mexikóban .................................................. 34 Lázár Nóra Kata: Egy európai kormányzás lehet ősége a nukleáris kérdések területén ..................... 44 Németh Zoltán György: Az orvos szakért ői bizonyítékok jellemz ői a büntet őeljárásban ................ 55 Nótári, Tamás: Legal and historical remarks on Carmina Salisburgensia ......................................... 63 Pokol Béla: Értelmi konkretizálás: Az Alaptörvény alkotmánybírósági értelmezésének vitái ......... 71 Szabó Judit: Az angolszász büntet őeljárás ideológiai alapjai és jellemz ői a kontradiktórius modell tükrében ............................................................................................................................................ 112 Vértesy László: Bankok vs. Alaptörvény ........................................................................................ 123 Vörös Imre: Az állami támogatások uniós jogi megítélésnek hatása a bels ő jogra ......................... 131 Recenziók Nótári, Tamás: Quintus Tullius Cicero kampánystratégiai kézikönyve angolul ............................. 163 Interjú -

Interview with Bahman Jalali1

11 Interview with Bahman Jalali1 By Catherine David2 Catherine David: Among all the Muslim countries, it seems that it was in Iran where photography was first developed immediately after its invention – and was most inventive. Bahman Jalali: Yes, it arrived in Iran just eight years after its invention. Invention is one thing, what about collecting? When did collecting photographs beyond family albums begin in Iran? When did gathering, studying and curating for archives and museum exhibitions begin? When did these images gain value? And when do the first photography collections date back to? The problem in Iran is that every time a new regime is established after any political change or revolution – and it has been this way since the emperor Cyrus – it has always tried to destroy any evidence of previous rulers. The paintings in Esfahan at Chehel Sotoon3 (Forty Pillars) have five or six layers on top of each other, each person painting their own version on top of the last. In Iran, there is outrage at the previous system. Photography grew during the Qajar era until Ahmad Shah Qajar,4 and then Reza Shah5 of the Pahlavi dynasty. Reza Shah held a grudge against the Qajars and so during the Pahlavi reign anything from the Qajar era was forbidden. It is said that Reza Shah trampled over fifteen thousand glass [photographic] plates in one day at the Golestan Palace,6 shattering them all. Before the 1979 revolution, there was only one book in print by Badri Atabai, with a few photographs from the Qajar era. Every other photography book has been printed since the revolution, including the late Dr Zoka’s7 book, the Afshar book, and Semsar’s book, all printed after the revolution8. -

Ali Pirzadeh Exploring the Historical Roots of Culture, Economics, And

Arts, Research, Innovation and Society Ali Pirzadeh Iran Revisited Exploring the Historical Roots of Culture, Economics, and Society Arts, Research, Innovation and Society Series Editors Gerald Bast, University of Applied Arts, Vienna, Austria Elias G. Carayannis, George Washington University, Washington, DC, USA David F.J. Campbell, University of Applied Arts, Vienna, Austria Editors-in-Chief Gerald Bast and Elias G. Carayannis Chief Associate Editor David F.J. Campbell More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/11902 Ali Pirzadeh Iran Revisited Exploring the Historical Roots of Culture, Economics, and Society Ali Pirzadeh Washington , DC , USA Arts, Research, Innovation and Society ISBN 978-3-319-30483-0 ISBN 978-3-319-30485-4 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-30485-4 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016935406 © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifi c statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 73-20,631

THE EFFORT TO ESCAPE FROM TEMPORAL CONSCIOUSNESS AS EXPRESSED IN THE THOUGHT AND WORK OF HERMAN HESSE, HANNAH ARENDT, AND KARL LOEWITH Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Olsen, Gary Raymond, 1940- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 10/10/2021 18:13:22 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/288040 INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Paga(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. -

Irreverent Persia

Irreverent Persia IRANIAN IRANIAN SERIES SERIES Poetry expressing criticism of social, political and cultural life is a vital integral part of IRREVERENT PERSIA Persian literary history. Its principal genres – invective, satire and burlesque – have been INVECTIVE, SATIRICAL AND BURLESQUE POETRY very popular with authors in every age. Despite the rich uninterrupted tradition, such texts FROM THE ORIGINS TO THE TIMURID PERIOD have been little studied and rarely translated. Their irreverent tones range from subtle (10TH TO 15TH CENTURIES) irony to crude direct insults, at times involving the use of outrageous and obscene terms. This anthology includes both major and minor poets from the origins of Persian poetry RICCARDO ZIPOLI (10th century) up to the age of Jâmi (15th century), traditionally considered the last great classical Persian poet. In addition to their historical and linguistic interest, many of these poems deserve to be read for their technical and aesthetic accomplishments, setting them among the masterpieces of Persian literature. Riccardo Zipoli is professor of Persian Language and Literature at Ca’ Foscari University, Venice, where he also teaches Conceiving and Producing Photography. The western cliché about Persian poetry is that it deals with roses, nightingales, wine, hyperbolic love-longing, an awareness of the transience of our existence, and a delicate appreciation of life’s fleeting pleasures. And so a great deal of it does. But there is another side to Persian verse, one that is satirical, sardonic, often obscene, one that delights in ad hominem invective and no-holds barred diatribes. Perhaps surprisingly enough for the uninitiated reader it is frequently the same poets who write both kinds of verse. -

On the Modern Politicization of the Persian Poet Nezami Ganjavi

Official Digitized Version by Victoria Arakelova; with errata fixed from the print edition ON THE MODERN POLITICIZATION OF THE PERSIAN POET NEZAMI GANJAVI YEREVAN SERIES FOR ORIENTAL STUDIES Edited by Garnik S. Asatrian Vol.1 SIAVASH LORNEJAD ALI DOOSTZADEH ON THE MODERN POLITICIZATION OF THE PERSIAN POET NEZAMI GANJAVI Caucasian Centre for Iranian Studies Yerevan 2012 Siavash Lornejad, Ali Doostzadeh On the Modern Politicization of the Persian Poet Nezami Ganjavi Guest Editor of the Volume Victoria Arakelova The monograph examines several anachronisms, misinterpretations and outright distortions related to the great Persian poet Nezami Ganjavi, that have been introduced since the USSR campaign for Nezami‖s 800th anniversary in the 1930s and 1940s. The authors of the monograph provide a critical analysis of both the arguments and terms put forward primarily by Soviet Oriental school, and those introduced in modern nationalistic writings, which misrepresent the background and cultural heritage of Nezami. Outright forgeries, including those about an alleged Turkish Divan by Nezami Ganjavi and falsified verses first published in Azerbaijan SSR, which have found their way into Persian publications, are also in the focus of the authors‖ attention. An important contribution of the book is that it highlights three rare and previously neglected historical sources with regards to the population of Arran and Azerbaijan, which provide information on the social conditions and ethnography of the urban Iranian Muslim population of the area and are indispensable for serious study of the Persian literature and Iranian culture of the period. ISBN 978-99930-69-74-4 The first print of the book was published by the Caucasian Centre for Iranian Studies in 2012. -

THE INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY for IRANIAN STUDIES انجمن بین املللی ایران شناسی ISIS Newsletter Volume 37, Number 1 May 2016

THE INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR IRANIAN STUDIES انجمن بین املللی ایران شناسی www.societyforiranianstudies.org ISIS Newsletter Volume 37, Number 1 May 2016 PRESIDENT’S NOTE Although the festivities of Nowruz 1395 have come to an end, nevertheless I would like to take this opportunity to wish all members of our society a very happy and prosperous 1395! Since the publication of the last issue of the newsletter, the online election for the new president was held and my good friend Touraj Daryaee now stands as the President-Elect. Also, Elena Andreeva and Afshin Marashi joined the Council. I am very grateful to the collective team of colleagues on the board for their commitment to our society. Preparation for the forthcoming Eleventh Biennial Conference of The International Society for Iranian Studies is underway and the head of the Conference Committee, Florian Schwarz, and Programme Committee Chair Camron Amin together with their colleagues on both committees are doing their best to make the Eleventh Biennial another successful conference, this time in Vienna. I look forward to seeing all our members at the beginning of August in Vienna. Touraj Atabaki Amsterdam, April 2016 The International Society for Iranian Studies Founded in 1967 ISIS 2016 OFFICERS ISIS Newsletter Volume 37, Number 1 May 2016 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE The second reason is that some years ago when we were on summer vacation 2016 AFRO-IRANIANS: in Iran with family and friends, I saw an Afro-Iranian man for the first time. We went to a football match between Bargh Shiraz FC and Aluminium Hormozgan FC. The TOURAJ ATABAKI AN ELEMENT IN A MOSAIC PRESIDENT man was the fan leader of the Hormozgan team and I was quickly drawn to the way the fans joyfully and rhythmically chanted for their team. -

In the Eyes of the Iranian Intellectuals of The

“The West” in the Eyes of the Iranian Intellectuals of the Interwar Years (1919–1939) Mehrzad Boroujerdi n 1929, after a lecture by Arnold Toynbee (from the notes of Denison Ross, the fi rst director of the School of Oriental and African Studies) on the subject of the modern- ization of the Middle East, a commentator said, Persia has not been modernized and has not in reality been Westernized. Look at the map: there is Persia right up against Russia. For the past hundred years, living cheek by jowl with Russia, Persia has maintained her complete independence of Russian thought. Although sixty to seventy percent of her trade for the past hundred years has been with Russia, Persia remains aloof in spirit and in practice. For the past ten years, Persia has been living alongside the Union of Socialist Soviet Republics, and has remained free from any impregnation by their basic ideas. Her freedom is due to her cultural independence. For the safety of Persia it is essential, if she is to continue to develop on her own lines, that she should not attempt modernization, and I do not think that the attempt is being made. It is true that the Persians have adopted motor-cars and in small way railways. But let us remember that the Persians have always been in the forefront in anything of that sort. The fi rst Eastern nation to enter the Postal Union and to adopt a system of telegraphs was Persia, which country was also among the fi rst of the Eastern nations to join the League of Nations and to become an active member. -

197 Comparative Literature in Iran

International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Development International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Development Online ISSN: 2349-4182, Print ISSN: 2349-5979, Impact Factor: RJIF 5.72 www.allsubjectjournal.com Volume 3; Issue 11; November 2016; Page No. 197-203 Comparative literature in Iran: Origin and development Mukhtar Ahmed Centre for Persian and Central Asian Studies/ SL/ JNU, New Delhi, India Abstract This paper seeks to trace the historical tracks of comparative literature in modern Iran. I am following the early footsteps of comparative literature of Iran through the life of Fatemeh Sayyah (1902-1947), who is credited to be the founder of the discipline of Comparative literature in Iran, which started off as discipline with the introduction of a literary program for the first time at Tehran University in 1938. The very first academic comparative work with respect to Persian literature was done by an Indian scholar Umar Bin Mohammad Daudpota almost 11 years before its introduction in Iranian university curriculum, in 1927 at Cambridge University, with the title of ‘The effect of Arabic poetry on Persian poetry’. As a discipline, throughout its journey that comparative literature encountered in Iran as far as its development is concerned has had to overcome obstacles in its way. Many a time the program faced its closures and reopening. The process of literary interaction with French literature, its impact on Iranian literature and the outcome of this process, which I believe is more out of a protest than anything else, though it was leveraged to some extent by Pahlavi dynasty in a bid to protect its claims for monarchy. -

KHERAD-DISSERTATION-2013.Pdf

Copyright by Nastaran Narges Kherad 2013 The Dissertation Committee for Nastaran Narges Kherad Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: RE-EXAMINING THE WORKS OF AHMAD MAHMUD: A FICTIONAL DEPICTION OF THE IRANIAN NATION IN THE SECOND HALF OF THE 20TH CENTURY Committee: M.R. Ghanoonparvar, Supervisor Kamran Aghaie Kristen Brustad Elizabeth Richmond-Garza Faegheh Shirazi RE-EXAMINING THE WORKS OF AHMAD MAHMUD: A FICTIONAL DEPICTION OF THE IRANIAN NATION IN THE SECOND HALF OF THE 20TH CENTURY by Nastaran Narges Kherad, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2013 Dedication Dedicated to my son, Manai Kherad-Aminpour, the joy of my life. May you grow with a passion for literature and poetry! And may you face life with an adventurous spirit and understanding of the diversity and complexity of humankind! Acknowledgements The completion of this dissertation could not have been possible without the ongoing support of my committee members. First and for most, I am grateful to Professor Ghanoonparvar, who believed in this project from the very beginning and encouraged me at every step of the way. I thank him for giving his time so generously whenever I needed and for reading, editing, and commenting on this dissertation, and also for sharing his tremendous knowledge of Persian literature. I am thankful to have the pleasure of knowing and working with Professor Kamaran Aghaei, whose seminars on religion I cherished the most. -

Philosophy of Power and the Mediation of Art:The Lasting Impressions of Artistic Intermediality from Seventeenth Century Persia to Present Shadieh Emami Mirmobiny

Maine State Library Digital Maine Academic Research and Dissertations Maine State Library Special Collections 2018 Philosophy of Power and the Mediation of Art:The Lasting Impressions of Artistic Intermediality from Seventeenth Century Persia to Present Shadieh Emami Mirmobiny Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalmaine.com/academic PHILOSOPHY OF POWER AND THE MEDIATION OF ART: THE LASTING IMPRESSIONS OF ARTISTIC INTERMEDIALITY FROM SEVENTEENTH CENTURY PERSIA TO PRESENT Shadieh Emami Mirmobiny Submitted to the faculty of The Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy May, 2018 Accepted by the faculty of the Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts in partial fulfillment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. COMMITTEE MEMBERS Committee Chair: Ali Anooshahr, Ph.D. Professor, Department of History University of California, Davis Committee Member: Christopher Yates, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Philosophy, and Art Theory Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts Committee Member: EL Putnam, Ph.D. Assistant Lecturer, Dublin School of Creative Arts Dublin Institute of Technology ii © 2018 Shadieh Emami Mirmobiny ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii “Do we need a theory of power? Since a theory assumes a prior objectification, it cannot be asserted as a basis for analytical work. But this analytical work cannot proceed without an ongoing conceptualization. And this conceptualization implies critical thought—a constant checking.” — Foucault To my daughter Ariana, and the young generation of students in the Middle East in search of freedom. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe a debt of gratitude to a number of people, without whose assistance and support this dissertation project would not have taken shape and would not have been successfully completed as it was. -

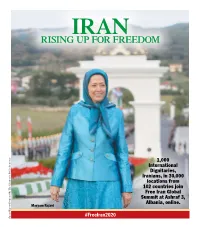

Rising up for Freedom

IRAN RISING UP FOR FREEDOM 1,000 International Dignitaries, Iranians, in 30,000 locations from 102 countries join Free Iran Global Summit at Ashraf 3, Albania, online. Maryam Rajavi #FreeIran2020 Special Report Sponsored The by Alliance Public for Awareness Iranian dissidents rally for regime change in Tehran BY BEN WOLFGANG oppressive government that has ruled Iran from both political parties participating has proven it can’t deliver for its people. tHe WasHInGtOn tImes since the Islamic Revolution of 1979. Leaders represented a who’s who list of American “The Iranian people want change, to of the NCRI, which is comprised of multiple “formers,” including former Sen. Joseph I. have democracy, finally to have human Iran’s theocracy is at the weakest point other organizations, say the council has seen Lieberman of Connecticut, former Penn- rights, to finally have economic wealth, of its four-decade history and facing un- its stature grow to the point that Iranian sylvania Gov. Tom Ridge, former Attorney no more hunger. The will of the people precedented challenges from a courageous officials can no longer deny its influence. General Michael Mukasey, retired Marine is much stronger than any oppressive citizenry hungry for freedom, Iranian dis- The NCRI has many American support- Commandant James T. Conway and others. measure of an Iranian regime,” said Martin sidents and prominent U.S. and European ers, including some with close relationships Several current U.S. officials also delivered Patzelt, a member of German Parliament. politicians said Friday at a major interna- to Mr. Trump, such as former New York remarks, including Sen.