Hazardous Digits: Telephone Keypads and Russian Numbers in Tbilisi, Georgia ⇑ Perry Sherouse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

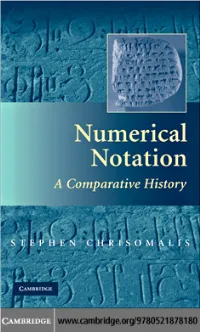

Numerical Notation: a Comparative History

This page intentionally left blank Numerical Notation Th is book is a cross-cultural reference volume of all attested numerical notation systems (graphic, nonphonetic systems for representing numbers), encompassing more than 100 such systems used over the past 5,500 years. Using a typology that defi es progressive, unilinear evolutionary models of change, Stephen Chrisomalis identifi es fi ve basic types of numerical notation systems, using a cultural phylo- genetic framework to show relationships between systems and to create a general theory of change in numerical systems. Numerical notation systems are prima- rily representational systems, not computational technologies. Cognitive factors that help explain how numerical systems change relate to general principles, such as conciseness and avoidance of ambiguity, which also apply to writing systems. Th e transformation and replacement of numerical notation systems relate to spe- cifi c social, economic, and technological changes, such as the development of the printing press and the expansion of the global world-system. Stephen Chrisomalis is an assistant professor of anthropology at Wayne State Uni- versity in Detroit, Michigan. He completed his Ph.D. at McGill University in Montreal, Quebec, where he studied under the late Bruce Trigger. Chrisomalis’s work has appeared in journals including Antiquity, Cambridge Archaeological Jour- nal, and Cross-Cultural Research. He is the editor of the Stop: Toutes Directions project and the author of the academic weblog Glossographia. Numerical Notation A Comparative History Stephen Chrisomalis Wayne State University CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo, Delhi, Dubai, Tokyo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521878180 © Stephen Chrisomalis 2010 This publication is in copyright. -

MUL TILANGUAGE TRANSLATION of NUMERALS by PROLOG Bengt

MUL TILANGUAGE TRANSLATION OF NUMERALS BY PROLOG Bengt Sigurd INTRODUCTION The present paper describes a program (Nummer.pro), which has been developed for PC (MSDOS) in PDC prolog (Prolog Development Center, DK-2605 Broendby). It translates numerals (English, Burmese, Georgian, French and Japanese) and is based on a general theory of numerals, which presumably can be applied to all numeral systems in the world, although with varying success - related to number of exceptions. Languages will show different types of deviations from the general model (cf below). The general model accounting for the structure of numerals is formalized by the following rule: Numer al --> ... (U G3) (U G2) (U Gl) (U GO) In this generative rule U isa unit numeral and G0,Gl,G2,etc. are group numerals. The English numeral "two hundred" consists of the unit (U) numeral "two" and the group (G) word "hundred", which is G2 in the formula. There are no other constituents in this case. An expression within parentheses is called a group constituent. The meaning (value) of such a group constituent is the meaning of the unit word multiplied by the meaning of the group word, in this case 2*100=200, as expressed in the ordinary (decimal) mathematical system. A numeral may consist of one or several such group constituents. The numeral "three hundred and thirty three" consists of three group constituents (disregarding "and"): (three hundred) (thir ty) (three) 117 Some of the irregularities hinted at above show up in this example. The unit numeral for 3 has different forms (the allomorphs three/thir) in its different occurrences and it seems to be more natural to treat thirty, and the numeral thirteen, as complexes not to be further analyzed synchronically (only etymologically). -

![Arxiv:1808.06068V1 [Cs.CL]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1268/arxiv-1808-06068v1-cs-cl-2721268.webp)

Arxiv:1808.06068V1 [Cs.CL]

SeVeN: Augmenting Word Embeddings with Unsupervised Relation Vectors Luis Espinosa-Anke and Steven Schockaert School of Computer Science and Informatics, Cardiff University, UK {Espinosa-AnkeL,SchockaertS1}@cardiff.ac.uk Abstract We present SeVeN (Semantic Vector Networks), a hybrid resource that encodes relationships between words in the form of a graph. Different from traditional semantic networks, these re- lations are represented as vectors in a continuous vector space. We propose a simple pipeline for learning such relation vectors, which is based on word vector averaging in combination with an ad hoc autoencoder. We show that by explicitly encoding relational information in a ded- icated vector space we can capture aspects of word meaning that are complementary to what is captured by word embeddings. For example, by examining clusters of relation vectors, we observe that relational similarities can be identified at a more abstract level than with tradi- tional word vector differences. Finally, we test the effectiveness of semantic vector networks in two tasks: measuring word similarity and neural text categorization. SeVeN is available at bitbucket.org/luisespinosa/seven. 1 Introduction Word embedding models such as Skip-gram (Mikolov et al., 2013a) and GloVe (Pennington et al., 2014) use fixed-dimensional vectors to represent the meaning of words. These word vectors essentially cap- ture a kind of similarity structure, which has proven to be useful in a wide range of Natural Language Processing (NLP) tasks. Today, one of the major applications of word embeddings is their interaction with neural network architectures, enabling a kind of generalization beyond those words that were only observed during training. -

A Study of Our Present Numbering System: an Histo

A STUDY OF OUR PRESENT NUMBERING SYSTEM: AN HISTO~t CAL A~RO&~H A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FUIJFILLMBNT OF THE REQUIREMBNTS FOR THE DE(~?.EE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE BY MAE FRANCES WIlSON DEPA1~rMBNT OF MATHEMATICS ATLANTA, GEORGIA AUGUST 196t~ ii ~‘- TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES. • . • • • • Iii Chapter I. INTRODUCTION. .• . 1 II. NU_~4ERATION . 3 III. SYSTE~ ND THEIR PROPERTIES. 10 B IBLIOGf?JkFHY. , • • . • • 22 ii EGYPTIAN NUMERALS I I A VtR.TICaL 10 (1 A HE~i.- BONE 10 A [email protected] I. 0~ A~~° A LÔTUS 1. ü~ I k POINTIkI6 IU A 6u9%8o1 FsU 1. 0 ~ A- (4111” 1W A-$TON~$JtM~VT Figure 1 iii AT ~ a.xn~ç~ ill III UU~Od,d, III UUU~Ø~ =(Ub4(QIJS-~o I) b4 (~c?I)/ ~b..cb1 l(1IVVU&~ =(V(oI)E09~h~Z III L)ULI = (i)S4-(o~)L 5L IIIL)L) (,)~-f-(oOZ = Ii V :~7:J ~ ~ (~~o” # ~ 0/)£ ~ (‘i, 01)1 ~1Q £ I S?~I~EJWnN NVIJ~J~-D~ A 6 —~(4oV4Q14.Q1 AAA >~~PI~P’>I~ L2 Q~. — Q?4O~ 1,1 A> II > 0l AAIAA~AA1L b AAAAAAA L 9 S ~AAA ~A4 Al Z A I ~~Wri/q fV~bNINQ7A~’d~ STht~3’~WnN ~io~ I~T~U1N ~TvINQ~UEya OOb, L~ Ob e b c9oo~’ LL8 ILOOL cOL X009 09 9 c?,QQS (LOS (LOOI7 71 Oh ~L- OQE D OO~ )I OZ 0~ 00/ 7 0/ ~IY~{~W11t~ )I~O S a.zn2T~ COb 00~ CCL 009 00.9 OOtT 001 002 00/ L~ L UQLL~ S~T3~QNnH Oh Q~OL 09 OS 0*701 OZ 0? SN3± b~~9S-&~ZI qLL[LLLLCt~~ S~LINfl $IV~WflN ~ 9 e.in2t~ ~,1- co’ 4- 01 itt b 37d WYX~ 9 -ç 4.7 z I 5 7j1≥13(AJPAJ 3~3/IVd4’I— 3S3IVIfI) 741>13W fiN ~‘flQ ~I~HflN ~S~vdvf-~9~NIHD L ‘~T~!i •~7’~74,4J Qb’ FQ~/ ~v ~, Ob~ ~J9h-6 ~ZL ‘q~’ wi ~44OA/ -% A’~VW..t f7~fs~3,4/g4/ ~ b VA L C’? ~ ~4 I Q’b’ 914 ~9A 000/ P~ ~ $~TVV~flN ~IEWV-flG$EIR CHI&PrER I INTRODUCTION The meaningful approach to the teaching of arithmetic is widely accepted. -

Georgian Language

M. Nikolaishvili N. Bagration-Davitashvili Georgian Language (Intensive Course) Tbilisi 2012 1 УДК 809.463.1 N67 The present work represents the English version of M.Nikolaishvili’s book «Грузинский Язык» («Georgian Language») published in 1999. which is recognised by the Ministry of Education of Georgia as a sound basic course text book of the Georgian Language for the non-Georgian students. The course includes all topics needed for everyday relations and also gives an idea of the basic grammatical peculiarities of the Georgian language. The book can be used as a self study course as well. Editor Doctor of Philological Sciences, Professor E. Babunashvili, K. Gelashvili Reviewers: Doctor of Philological Sciences, Professor F. Uturgaidze, Professor T. Injia Proof Reader: Lydia West. Technical Editor: P. Korkia All rights reserved. © M. Nikolaishvili, N. Bagration-Davitashvili ISBN 978-9941-0-4539-4 BY THE AUTHOR The present book represents a basic course of the Georgian language, with a preface stating the general characteristics of the grammar of this language. The book begins with the study of writing and reading. Then follow texts, that encompass all the main topics of the language spoken in everyday life and are intended for an exact knowledge of the spoken Georgian language. There are ten topics in the book and each of them is divided into sections short texts, composed of the most frequently used words, grammatical explanations, the need of which may arise from the text. The explanations concern other forms of individual words marked with an asterisk. Ibidem are exercises, lexical groups connected with a topic, and at the end, a text that includes represented dialogues on certain subjects. -

Chapter 7 MISCELLANEOUS NUMBER BASES. the VIGESIMAL

The Number Concept: Its Origin and Development By Levi Leonard Conant Ph. D. Chapter 7 MISCELLANEOUS NUMBER BASES. THE VIGESIMAL SYSTEM. In its ordinary development the quinary system is almost sure to merge into either the decimal or the vigesimal system, and to form, with one or the other or both of these, a mixed system of counting. In Africa, Oceanica, and parts of North America, the union is almost always with the decimal scale; while in other parts of the world the quinary and the vigesimal systems have shown a decided affinity for each other. It is not to be understood that any geographical law of distribution has ever been observed which governs this, but merely that certain families of races have shown a preference for the one or the other method of counting. These families, disseminating their characteristics through their various branches, have produced certain groups of races which exhibit a well-marked tendency, here toward the decimal, and there toward the vigesimal form of numeration. As far as can be ascertained, the choice of the one or the other scale is determined by no external circumstances, but depends solely on the mental characteristics of the tribes themselves. Environment does not exert any appreciable influence either. Both decimal and vigesimal numeration are found indifferently in warm and in cold countries; in fruitful and in barren lands; in maritime and in inland regions; and among highly civilized or deeply degraded peoples. Whether or not the principal number base of any tribe is to be 20 seems to depend entirely upon a single consideration; are the fingers alone used as an aid to counting, or are both fingers and toes used? If only the fingers are employed, the resulting scale must become decimal if sufficiently extended. -

Requirel'fflnts for ATLANTA, GEORGIA

ON FRACTIONS IN SOME NUMERATION SYSTEMS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREl'fflNTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE BY THEODORE ROOSEVELT NICHOLSON DEPARTMENT OF MATHEMATICS ATLANTA, GEORGIA JANUARY 1965 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION 1 A, Historical Background 1 B. Definitions 3 CHAPTER II FRACTIONS IN THE DECIMAL SYSTEl'I OF NUMERATION.... $ A. General Representation of Fractions 5 B. Conversion of Base Ten Fractions in Other Numeration Systems 5 C. Converting Any Decimal Fraction to Any Other System 8 D. Conversion of Fractions in Non-decimal Systems to Fractions in the Decimal System... 11 CHAPTER III ARITHMETICAL COMPUTATIONS 13 A. Addition of Fractions in Different Numeration Systems 13 B. Multiplication of Fractions in Different Numeration Systems 15 BIBLIOGRAPHY 18 ii \ « CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Much enphasis has been put on the expression of integers in base systems other than ten, but very little work has been done in the field of numeration systems regarding expression of fractions. Currently, many textbook writers are including this material in books for elemen- tary, junior and senior high schools. Many believe that the conversion of integers from one numeration system to another increases the stu¬ dent's computational ability. The author of this thesis through years of teaching experience has observed repeatedly that students experience great difficulty with computations involving fractions, and since stu¬ dents develop skills in arithmetical computations to a high degree by the use of integers and fractions, it is the purpose of this thesis to present methods of converting fractions from one system of numeration to another. -

Incorporating Different Number Bases Into the Elementary School Classroom

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 8-2006 Incorporating Different Number Bases into the Elementary School Classroom. Crystal Michele Hall East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Recommended Citation Hall, Crystal Michele, "Incorporating Different Number Bases into the Elementary School Classroom." (2006). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2220. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/2220 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Incorporating Different Number Bases into the Elementary School Classroom _____________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of Mathematics East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science in Mathematical Science _____________________ by Crystal Michele Hall August, 2006 _____________________ Anant Godbole, Chair George Poole Rick Norwood Keywords: Base, Rote, Elementary, Education, Place value ABSTRACT Incorporating Different Number Bases into the Elementary School Classroom by Crystal Michele Hall Since becoming an educator and gaining extensive classroom experience, I have concluded that it would be beneficial to elementary school children to learn other number bases and their basic functions and operations. In this thesis, I have developed five units involving lesson plans for incorporating various number bases into the existing curriculum. -

A Short Research in Danish Cardinal and Ordinal Numerals on Indo-European Background

FOLIA SCANDINAVICA DOI: 10.1515/fsp-2015-0002 VOL. 16 POZNA Ń 2014 A SHORT RESEARCH IN DANISH CARDINAL AND ORDINAL NUMERALS ON INDO-EUROPEAN BACKGROUND BŁA ŻEJ GARCZY ŃSKI Adam Mickiewicz University in Pozna ń ABSTRACT . The article focuses on the Danish numerals 1-1000. It presents their Proto-Indo-European, Proto-Germanic, Old Danish and present forms whilst providing additional information on their development and corresponding numerals in other European languages. It focuses primarily on the vigesimal counting system, whose traces can be found in Danish, and which is the source of some unique forms unseen in other languages. Therefore, special attention is paid to the numerals of the series 50-90. Though these appear to be unique and exotic, the article shows that they are not to be perceived as an anomaly but rather a different path of development within the language Moreover, a brief explanation of the origins of the vigesimal system in Danish is provided. Also, several units of measurement showing traces of the vigesimal, duodecimal and sexagesimal systems are discussed. Finally, language reforms aimed at changing the numeral forms will be shortly portrayed. 1. INTRODUCTION Danish is, as are its Scandinavian and Germanic relatives, a descendant of Proto-Indo-European (PIE). Therefore, its numeral forms are chiefly inherited from PIE. In the article, Danish cardinal and ordinal numbers will first be investigated by shortly describing the PIE counting system and the possibility of its reconstruction. Further on, several counting systems that have different numeral bases which can be found among European languages will be distinguished. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University Press

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-87818-0 - Numerical Notation: A Comparative History Stephen Chrisomalis Index More information Index Numerical notation systems are indexed alphabetically by name of system (e.g., “Aramaic numerals”). Number words are indexed under “lexical numerals, Language-name” (e.g., “lexical numerals, English”). Writing systems are indexed under “writing system, Script-name” (e.g., “writing system, Greek”). abacists 123, 147, 220 Aegean numerical notation systems abacus 97, 104, 115–6, 123–4, 144, 147, 182, 218, See Linear A / Linear B numerals 220, 259, 264, 266, 269, 315 Afro-Asiatic languages 319 Gerbert’s abacus 220 Agabo 152 ghubar 218 Agora (Athens) 100, 142 Greco-Roman 266 Agrippa of Nettesheim 354 Inka 315 Ahar stone inscriptions 197 pebble-board 97, 104, 144 Akinidad stela 52, 53 and Roman numerals 115–16, 124 Akkadians 71, 243–4, 248 schety 182 Akko 76 soroban 264 aksharapallî numerals 205, 210–13 suan pan 259, 264, 269 Aksumites 153 Abaj Tabalik 288 Albelda (Logrono), Spain 219 Abbasid caliphate 219, 403 al-Biruni 170 Abraham ibn Ezra 159, 184, 216, 237 Alexander the Great 143, 388 abstract numbers 18, 237 Alexandria 153, 192 abugida See alphasyllabary Alexandrine conquest 252, 258, 413 Abusir papyri 43, 47 Alexandrine period 104, 143, 192 Achaeans 64 Algorismus vulgaris 221 Achaemenid Empire 73, 76, 86, 83, 92, 142, 249, algorithmists 123, 147, 221 256–8, 413 al-Jāhiz 215 acrophonic principle 102–3, 107–8, 128, 435 al-Khwārizmī, Muhammad ibn Mūsā 128, 166, Adab al-kuttāb 215 214, 217 Adair, James 348 -

Remapping the Affordances of Russian Language in Tbilisi, Georgia

QUALITY, COMFORT, AND EASE: REMAPPING THE AFFORDANCES OF RUSSIAN LANGUAGE IN TBILISI, GEORGIA by Perry Maxfield Waldman Sherouse A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in the University of Michigan 2014 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Alaina Lemon, Chair Professor Michael Makin Professor Bruce Mannheim Associate Professor Paul Manning, Trent University Acknowledgments This dissertation would not been possible without funding from the International Institute at the University of Michigan. From the University of Michigan, I also received grants from the Center of Russian and East European Studies, Rackham Graduate School, and the Department of Anthropology. Thank you to my Georgian teachers: Tamriko Bakuradze, Dodona Kiziria, Ramaz Kurdadze, Nestan Ratiani, and Nana Tevzaia. For language study, I am grateful to have received Title VIII grants and FLAS grants for both Russian and Georgian. Thank you to Svitlana Rogovyk at the University of Michigan for an engaging Russian class. Without my Georgian friends and contacts none of this would have been possible. Thanks to the coaches at GEOWF, especially Giorgi Asanidze, Avtandil Gakhokidze, Ramaz Gurgenidze, Temur Janjgava, Gela Makharashvili, Aleko Nozadze, and Guram Parulava. To the weightlifters, keep training hard. Thank you to my amazing research assistant, Elene Chumburidze. Thank you to those who provided me with conversation, ideas, contacts, and inspiration: Rusiko Amirejibi-Mullen, Nargiza Arjevanidze, Tinatin Bolkvadze, Hans Gutbrod, Lamara Kadagidze, Ani Kurdgelashvili, Neli Melkadze, Manana Tabidze, Natia Tananashvili, and Lika Tsuladze. Thanks to Dato and Lika for your hospitality, and to Vakho for hypnotizing me so I could learn Georgian.