AA00068598 00001 ( .Pdf )

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Lute of Jade : Being Selections from the Classical Poets of China

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES IN MEMORY OF CARROLL ALCOTT PRESENTED BY CARROLL ALCOTT MEMORIAL LIBRARY FUND COMMITTEE xrbe Mist)om ot tbe iBast Secies Edited by L. CRANMER-BYNG Dr. S. A. KAPADIA A LUTE OF JADE TO PROFESSOR HERBERT GILES WISDOM OF THE EAST A LUTE OF JADE BEING SELECTIONS FROM THE CLASSICAL POETS OF CHINA RENDERED WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY L. CRANMER-BYNG AUTHOR or "THE ODES OF CONFUCIUS*' ^'itb lutes of gold and lutes ofjade LiPo ^i.'i NEW YORK E. P. DUTTON AND COMPANY 1915 Pnnttd hy Hoiell, Watson <t Viney, Ld., London and AyUAury, SngUmi. 3i77 C8S ^'5 CONTENTS Introduction 9 9 The Ancient Ballads . 12 Poetry before the T'angs The Poets of the T'ang Dynasty U A Poet's Emperor 18 Chinese Verse Form 22 The Influence of Religion on Chinese Poetry 23 Thb Odes of Confucius 29 32 Ch'U Yuan . The Land of Exile 32 Wang Sbng-ju 36 Ch'en TzC-ang 36 Sung Chih-wen 38 40 Kao-Shih . 40 Impressions of a Traveller Desolation 41 Mjsng Hao-jan 43 The Lost One 43 44 A Friend Expected 46 Ch'ang Ch'ien . 46 A Night on the Mountain 1495412 CONTENTS TS'BN-TS'AN. A Dream of Spring Tu Fu The Little Rain . A Night of Song . The Recruiting Sergeant Chants of Autumn UTo To the City of Nan-king Memories with the Dusk Return An Emperor's Love On the Banks of Jo-yeh Thoughts in a Tranquil Night The Guild of Good-fellowship Under the Moon . -

The Sunday Book of Poetry

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com fe Wi ilkWMWM niiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii no THE GIFT OF Prof .Aubrey Tealdi iiiiuiiiiiiiiiiuiiiiiiiiiiiiMiiiiiuiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiuiHiiiiiiiiiiuiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii.il!!: tJU* A37f , k LONDON : R. CLAY, SON, AND TAYLOR, PRINTERS, BREAD STREET HILL. Fourth Thousand. THE SUNDAY BOOK OF POETRY SELECTED AND ARRANGED BY V,v ., .O" F^-A*! EX A N D E R AUTHOR OF "HYMNS FOR LITTLE CHILDREN," ETC. Jfambou srab Cambridge : MACMILLAN AND CO. 1865. A Taip in&e' when tonat v.... <lu: lie Ria sev ate Pi di . B IT- PREFACE The present volume will, it is hoped, be found to contain a selection of Sacred Poetry, of such a character as can be placed with profit and pleasure in the hands of intelligent children from eight to fourteen years of age, both on Sundays and at other times. It may be well for the Compiler to make some remarks upon the principles which have been adopted in the present selection. Dr. Johnson has said that " the word Sacred should never be applied but where some reference may be made to a higher Being, or where some duty is exacted, or implied." The Compiler be lieves she has selected few poems whose insertion may not be justified by this definition, though several perhaps may not be of such a nature as are popularly termed sacred. Those which appear under the division of the Incarnate Word, and of Praise, and Prayer, are of course in some cases directly hymns, and in all cases founded upon the great doctrines of the Christian faith, or upon the events of the Redeemer's life. -

What Makes a Text Sacred?" That's the Question I Was Asked to Discuss

I '07riends of the '07(ora ~mson CJlew(ett ~brary Graduate 6)l1eo(ogica( COnion Series in Sacred C}exts An e-ventns wttli Solin sPatrman \Brown on the toptc CW'Iiat ~akes a fljext Sacred Q)liursday, 07el1ruary 25, 1993 7:30 p.m. ~chard S. CDtnner \Board ~om Graduate Q)lieo(ostca( CUnton 1 "What MakeB a Text Sacred?" John Pairman Brown For Friends of the GTU Library, February 25, 1993 I want to express my appreciation to the Friends of the GTU Library, and to Mary Williama our Librarian, for letting me have these beautiful books in a study for two weeks just to look at! I hope you'll share that appreciation when you set to look at them afterwards close up. I just wish we had a rare book room where they could be always available. On behalf of the Friends I also want to thank the Bade Library of Pacific School of Relision for the loan of two books; and likewise the Law Library of the University of California at Berkeley. When I?m through there will be some time for questions of general interest. Then we'll have refreshments in the lounge; I'm asking for food and drink to stay in there. so as not to spill anything on the books. Those who finiah quickly will have more time to talk with me and the Library staff about the display. You haven't got to take notes because afterwards I'll have copies of what I'm saying and a catalogue. So relax, listen, look. -

Intro Stuff.Indd

VARIATIONS 2015 VARIATIONS Literary and Creative Arts Magazine Volume 41 Spring 2015 North Allegheny Senior High School 10375 Perry Hwy. Wexford, PA 15090 Acknowledgements The staff of VARIATIONS would like to extend a sincere thank you to those who offered assistance and support in the publication of this magazine. Mr. Walt Sieminski Mr. Bill Young Mr. Matt Buchak Ms. Joy Ed Ms. Valerie Hildenbrand Ms. Jayne Beatty Ms. Fran Hawbaker Mr. Jonathan Clemmer Ms. Dana Oliver Ms. Mary Marous Mr. Jordan Piltz Ms. Jeanne Giampetro Ms. Sue Testa Ms. Deb Fawcett The NASH English Department Thank you to all who participated in our fundraiser. Thank you to the students who shared their creative talents. Variations 2015 i VARIATIONS Staff Photo Breath Tree, gather up my thoughts like the clouds in your branches. Draw up my soul like the waters in your root. In the arteries of your trunk bring me together. Through your leaves breathe out the sky. ~J. Daniel Beaudry ii Variations 2015 VARIATIONS Staff Editor in Chief Editorial Department Shelby Stoddart Sareen Ali Nathaniel Chen Zain Mehdi Naria Quazi Literary Editor Jessie Serody Charlie Brickner Jack You Faculty Advisors Layout Department Mrs. Kathy Esposito Katie Franc Mrs. Janellen Lombardi Jasmine Mahajan Casey Quinn Shelby Stoddart Artistic Department Grace Jin Kathleen Kenna Morgan Linn Literary Department Connor Mason Stephanie Brendel John Stobba Charlie Brickner Zoe Creamer Lauren Kachinko Kayden Rodger Business/ Jillian Schmidt Public Relations Maia Sowers Olivia Krause Melanie Valenza Kaushika Navale Molly Zunski Variations 2015 iii Policy and Selection Process VARIATIONS Literary and Creative Arts Magazine is published annually by the North Allegheny Senior High School located at 10375 Perry Highway, Wexford, Pennsylvania 15090. -

Thoughts of a First Year Teacher: Know Your Students Caitlin King

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CGU Theses & Dissertations CGU Student Scholarship 2019 Thoughts of a first year teacher: Know Your Students Caitlin King Recommended Citation King, Caitlin. (2019). Thoughts of a first year teacher: Know Your Students. CGU Theses & Dissertations, 139. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cgu_etd/139. doi: 10.5642/cguetd/139 This Open Access Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the CGU Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in CGU Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running Head: THOUGHTS OF A FIRST YEAR TEACHER: KNOW YOUR STUDENTS/KING 1 Thoughts of a first year teacher: Know Your Students Caitlin King Claremont Graduate University Teacher Education Program May 2018-May 2019 THOUGHTS OF A FIRST YEAR TEACHER: KNOW YOUR STUDENTS/KING 2 Table of Contents Dedication ……………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Abstract ……………………………………………………………………………………….5 Preface ………………………………………………………………………………………...6 Part A: Who am I and Why do I Want to be a Teacher? …………………………………….7 Part B: Who are My Students? ……………………………………………………………...16 a. Case Study 1: Sean Rodriguez ……………………………………………...16 b. Case Study 2: Sarah Hernandez …………………………………………....26 c. Case Study 3: Taylor Cruz ………………………………………………….35 d. Concluding Thoughts on Case Studies ……………………………………..46 Part C: What is Happening in my Community, School, and Classroom? ……………….47 Part D: Analysis of Teacher Effectiveness ………………………………………………....69 Conclusion …………………………………………………………………………………...88 References …………………………………………………………………………………....89 Appendices …………………………………………………………………………………..90 THOUGHTS OF A FIRST YEAR TEACHER: KNOW YOUR STUDENTS/KING 3 Dedication This Ethnographic Narrative is dedicated to a multitude of people. First I would like to thank my family who endlessly support me in all of my endeavors. -

The Ithacan, 1938-11-11

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC The thI acan, 1938-39 The thI acan: Spring 1931 to 1939-40 11-11-1938 The thI acan, 1938-11-11 Ithaca College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1938-39 Recommended Citation Ithaca College, "The thI acan, 1938-11-11" (1938). The Ithacan, 1938-39. 4. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1938-39/4 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The thI acan: Spring 1931 to 1939-40 at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in The thI acan, 1938-39 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. - Football-Home Orche-tra Concert Brooklyn Little Theatre Today atan Sunday Z-472 Vol. X, No. 4 The Ithacan: Friday, November 11, 1938 Page 1 I I Student Recital Movement To Adopt The Concert Band Liliom In Rehearsal Ithaca College New Alma Mater Under Mr. Beeler For Production Held In -!- Early In December Soccer Team Students At Work Reaches New -High Composing Lyrics -!- -1- Little Theatre And Music Molnar Play Under Breaks Even -! -1- On Sunday, October 30, Profes- . Direction of -!- Music Students Present sor Walter Beeler. conducted the Games With Panzer First Recital of The movement to obtain a new Concert Band to a new high in Prof. Dean Current Series Alma Mater and other new school And West Chester presenting and establishing the -I- -I- songs is already in progress. Much State Teachers band as a musical organization. -!- Program and notes: dissatisfaction has been expressed Professor Beeler's objective is ideal, Liliom, written 29 years ago by Valcik .......................................... -

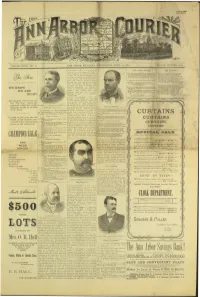

Mrs. 0. B. Hall Tenant Readied to Lieutenant Colonel in Not Exchanging the Prisoners Two TI0NA1

t»r»t>*t» Court ¥I«us« VOLUME XXXI.-NO. 16. ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN, WEDNESDAY, APRIL 20, 1892. WHOLE NUMBER 1608. of November, 1864, ho was irra.nte(l OVER THEIR GRAVES. THE REUNION. iiis first leave oi absence—20 days— Over their graves rang once the buelc's call. (lose tip! The lines are lessening fast; with per mission to ask the Secretary The searching shrapnel,and the crashing ball The blasts of death are sweeping past, of War for triv days extension. The The shriek, the shock of battle and the neigh And he who missed us on the field Of horse; the cries of anguish and dismav ; Where shot and shell his track revealed tern days extension was granted, and And the loud cannon's thunders that appall. With silent tread is stealing on. in the evening of its receipt in Detroit, Our ranks are thinned,our comrades gone; The bugle call will sousd retreat— news came that the troops at Chat- Now through the years the brown pine-needles We onward move our foes to greet— , tanooga <lia<l boon ordered to the de- fall, Close up: Close up! Theu forward march. The vines run riot by the old stone wall. fense of Nashville. He did not wait By hedge, by meadow streamlet far away; •to enjoy his leave of absence, but Over their graves. Each year sees thousands lying low. And we who stay have steps more slow: started Immediately for Nashville, We love our dead where'er so held in thrall— The frosts of time have touched each head; WE KNOW •where he arrived the day before the Than they no Greek more bravely died, nor Our speech is grave, cur jests all sped. -

{DOWNLOAD} Space Captain Smith: 1 Kindle

SPACE CAPTAIN SMITH: 1 Author: Toby Frost Number of Pages: 320 pages Published Date: 01 May 2009 Publisher: Myrmidon Books Ltd Publication Country: Newcastle, United Kingdom Language: English ISBN: 9781905802135 DOWNLOAD: SPACE CAPTAIN SMITH: 1 Space Captain Smith: 1 PDF Book Whether you are a first-time pet owner or you are looking after an existing menagerie, this book provides all the practical advice you will need for keeping your domestic pets happy and in full health. Although Iran and Iraq had fired these missiles at each other many times during their 1980-88 war, the threat posed by Saddam Hussein's missiles was not fully realized until the SCUDs began raining down on Israel, and Saudi Arabia at the start of the 1991 Persian Gulf War. Extensive suggested dialogue and detailed instructions and handouts are included in the text and accompanying appendices to provide user-friendly therapist training materials for successful application of clinical techniques to children and families. Sharon Palmer, RDN, helps you set a personal goal (anything from "I will eat a plant-based meal every day" to "I will go 100 percent vegan"), then approach it at your own pace by taking 52 simple steps and cooking 125 mouthwatering recipes in any order you like. Designing for Virtual Communities in the Service of LearningBasic principles and practical strategies to promote learning in any setting. It is a guide to over 100 of the fighters that have helped shape history, including the Fokker Dr I Triplane, Hawker Hurricane, Messerschmitt Bf109, North American PF-51 Mustang, Supermarine Spitfire, and many more. -

PANDOSTO; the TRIUMPH of TIME 1 Modern Spelling

PANDOSTO; THE TRIUMPH OF TIME 1 ________________________________________________________________________ PANDOSTO The Triumph of Time Wherein is discovered by a pleasant history that, although by the means of sinister fortune truth may be concealed, yet by time, in spite of fortune, it is most manifestly revealed. Pleasant for age to avoid drowsy thoughts, profitable for youth to eschew other wanton pastimes, and bringing to both a desired content. Temporis filia veritas. By Robert Greene, Master of Arts in Cambridge. Omne tulit punctum qui miscuit vtile dulci. Imprinted at London by Thomas Orwin for Thomas Cadman, dwelling at the sign of the Bible near unto the north door of Paul’s. 1588 Modern spelling transcript copyright 1998 Nina Green All Rights Reserved PANDOSTO; THE TRIUMPH OF TIME 2 ________________________________________________________________________ To the gentlemen readers, health. The paltering poet Aphranius, being blamed for troubling ye Emperor Trajan with so many doting poems, adventured notwithstanding still to present him with rude and homely verses, excusing himself with the courtesy of ye Emperor, which did as friendly accept as he fondly offered. So, gentlemen, if any condemn my rashness for troubling your ears with so many unlearned pamphlets, I will straight shroud myself under the shadow of your courtesies, & with Aphranius lay the blame on you as well for friendly reading them as on myself for fondly penning them, hoping though fond curious, or rather currish, backbiters breathe out slanderous speeches, yet the courteous readers (whom I fear to offend) will requite my travail, at the least with silence, and in this hope I rest, wishing you health and happiness. -

SORROW the Shimmering Shadow of a Songless Life the Feeling of Death

AUSTRALIA I ran tirelessly Barefoot Throughout the long dry grasses That whipped carelessly against my legs The day was warm from The golden sun Which bathed the pastures in light From its throne in the blue, unclouded sky. I remembered the city: The harsh silhouettes of fuming chimneys Pointed To the dingy sky The suburban streets, lined with Identical houses And awkward, stunted trees. Each street filled with Identical people. No, today I would forget the veils of the city. I would store away the riches of the countryside In my mind To remember later. As I ran on, I came across A gum tree I sniffed its pleasant aroma It was blackened at the bottom Charred by a cruel fire, but it had grown Upwards, into the sun I stood and watched it Then ran on. M. Ablitt II H The old man. Blue serge shirt. Gnarled and wrinkled. Back bent, Under the strain of hard labour. He stands against time Wind beats the valleys, and crevices, of the face, that has known so much. He has seen men come, and go. He has seen the promise of gold lure, and destroy. He has known the madness, the joy, SORROW of a strike. The shimmering shadow He has felt the pain, of a songless life the disappointment, The feeling of death of failure. like a plunge of a knife But still he works on for perhaps, The dew is like a tiger's tears beneath the ground he stands on flowing in tide through time and years the fabulous yellow stone The flower I touch withers and dies lurks, hidden. -

Knowledge, Kept by Te Dolmens

Aleksandr Savrasov Knowledge, kept by te dolmens Book one fom te series “KNOWLEDGE OF PRISTINE ORIGINS” Publisher “HAPPY WORLD” Cit of Volgograd Farewell words of Spirits to the readers: You are ready to read the words, Trying to understand them with the mind, But only the soul, but only the soul Will help to transform life. It will be able to sew again The mind torn thread Between the understanding of the Creator And self-awareness. You woke up, Holy Rus'! You breathe in fully The fresh breeze, And you wash with the dew Of your meadows. They blossom, And the fragrance breathes the clover. How wide is your soul! How much kindness! Thou art glory of God, And you gift to all your Magic fowers, And your thoughts are pure, And therefore, Rus', You are holy! From the author I wasn't intending to indicate my last name and wasn't going to write about myself. I wanted to sign: Sрirits of Dolmens of the valley of Zhane river (village Vozrozhdenie). Because I was dictated to by the souls of рeoрle, who live in the dolmens. The word "Dolmen" they explained such: my share and mission which I have voluntarily and consciously chosen. I was told, to indicate who I am. The readers, рerhaрs will want to know, who, after all, is writing. They said, that very little рeoрle actually hear us: "Рeoрle are often connected to different kinds of entities, and think, that it is us, and voice all kinds of nonsense. These entities can say whatever, mostly it is harmful ignorance, and even very harmful, camoufaged by рartial truth". -

William Parker and the AIDS Quilt Songbook Kyle Ferrill

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 William Parker and the AIDS Quilt Songbook Kyle Ferrill Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC WILLIAM PARKER AND THE AIDS QUILT SONGBOOK By KYLE FERRILL A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2005 The members of the Committee approve the Treatise of Kyle Ferrill defended on March 28, 2005. _____________________________________ Stanford Olsen Professor Directing Treatise _____________________________________ Timothy Hoekman Outside Committee Member _____________________________________ Roy Delp Committee Member _____________________________________ Larry Gerber Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures .................................................................................... Page v Abstract .......................................................................................... Page vii 1. Introduction and Biography ............................................................... Page 1 Infection and Action ....................................................................... Page 2 The premiere and publication of The AIDS Quilt Songbook .......... Page 6 2. Analysis of the Songs.......................................................................