Review of Stefan C. Reif, a Jewish Archive from Old Cairo: the History of Cambridge University's Genizah Collection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyrighted Material

chapter 1 life and works nlike most medieval Jewish philosophers, about whom very little is known, Maimonides provided future generations with ample informa- Ution about himself in letters and documents; many of these docu- ments have been preserved in part in the Cairo Geniza, a repository of discarded documents discovered over a century ago in the Ben Ezra synagogue of Fustât (Old Cairo) where Maimonides lived. From these snippets of texts, scholars have been able to reconstruct at least some details surrounding Maimonides’ life. He was known by several names: his original Hebrew name Moses ben Maimon; his Latinized name Maimonides; the Hebrew acronym RaMBaM, standing for Rabbi Moses ben Maimon; his Arabic name al-Ra’is Abu ‘Imran Musa ibn Maymun ibn ‘Abdallah (‘Ubaydallah) al-Qurtubi al-Andalusi al-Isra’ili; the honorific title “the teacher [ha-Moreh]”; and of course “the great eagle.” In this chapter I provide a brief synopsis of Maimonides’ intellectual bio- graphy, against the backdrop of twelfth-century Spain and North Africa. Recent biographies by Kraemer and Davidson have provided us with a detailed reconstruction of Maimonides’ life, drawn from Geniza fragments, letters, observations by his intellectual peers, and comments by Maimonides himself.1 We shall consider, ever so briefly, important philosophical influences upon Maimonides; scholars have explored in great detail which philosophers – Greek, Jewish, and Arabic – were most influential upon his intellectual development. I will then discuss Maimonides’ major philosophical works, most of which we shall examine in more detail in subsequent chapters. Maimonides’COPYRIGHTED Life MATERIAL Moses ben Maimon was born in Cordova, Spain in 1135/8 and died in Cairo in 1204. -

Toolkit for Genizah Scholars: a Practical Guide for Neophytes

EAJS SUMMER LABORATORY FOR YOUNG GENIZAH RESEARCHERS Institut für den Nahen und Mittleren Osten, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, München, 6–7 September 2017 Toolkit for Genizah Scholars: A Practical Guide for Neophytes Compiled by Gregor Schwarb (SOAS, University of London) A) Introductory articles, general overviews, guides and basic reference works: Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2nd edition, vol. 16, cols. 1333–42 [http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/genizah- cairo]. Stefan REIF et al., “Cairo Geniza”, in The Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World, vol. 1, ed . N. Stillman, Leiden: Brill, 2010, pp. 534–555. Nehemya ALLONY, The Jewish Library in the Middle Ages: Book Lists from the Cairo Genizah, ed. Miriam FRENKEL and Haggai BEN-SHAMMAI with the participation of Moshe SOKOLOW, Jerusalem: Ben-Zvi Institute, 2006 [Hebrew]. An update of JLMA, which will include additional book lists and inventories from the Cairo Genizah, is currently being prepared. Haggai BEN-SHAMMAI, “Is “The Cairo Genizah” a Proper Name or a Generic Noun? On the Relationship between the Genizot of the Ben Ezra and the Dār Simḥa Synagogues”, in “From a Sacred Source”: Genizah Studies in Honour of Professor Stefan C. Reif, ed. Ben Outhwaite and Siam Bhayro, Leiden: Brill, 2011, pp. 43–52. Rabbi Mark GLICKMAN, Sacred Treasure: The Cairo Genizah. The Amazing Discoveries of Forgotten Jewish History in an Egyptian Synagogue Attic, Woodstock: Jewish Lights Publishing, 2011. Adina HOFFMAN and Peter COLE, Sacred Trash: The Lost and Found World of the Cairo Geniza, New York: Nextbook, Schocken, 2010. Simon HOPKINS, “The Discovery of the Cairo Geniza”, in Bibliophilia Africana IV (Cape Town 1981). -

Redefining Urban Spaces in Cairo at the Turn of the 19 Th and 20 Th

Redefining Urban Spaces in Cairo at the Turn of the19 th and 20 th Centuries Jean-Luc Arnaud, Jean-Charles Depaule To cite this version: Jean-Luc Arnaud, Jean-Charles Depaule. Redefining Urban Spaces in Cairo at the Turn of the19th and 20 th Centuries. Ostle, Robin. Sensibilities of the Islamic Mediterranean, I. B. Tauris, pp.295-312, 2008. halshs-01225162 HAL Id: halshs-01225162 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01225162 Submitted on 5 Nov 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Arnaud 55 (avec J.-C. Depaule) – Redefining Urban Spaces in Cairo at the Turn of the 19th and 20th Centuries Redefining Urban Spaces in Cairo at the Turn of the 19th and 20th Centuries D’après : Jean-Luc Arnaud et Jean-Charles Depaule, "Redefining Urban Spaces in Cairo at the Turn of the 19th and 20th Centuries", chap. 16 de Robin Ostle (ed.), Sensibilities of the Islamic Mediterranean, Londres, I.B. Tauris, 2008, p. 295-312 Résumé Au départ de cette contribution il y a, notamment, une sorte de bizarrerie que l'on observe au Caire dans le vocabulaire urbain. -

1 Between Egypt and Yemen in the Cairo Genizah Amir Ashur Center

Between Egypt and Yemen in the Cairo Genizah Amir Ashur Center for the Study of Conversion and Inter-religious Encounters, Ben Gurion University, the Interdisciplinary Center for the Broader Application of Genizah Research, University of Haifa, and the Department of Hebrew Culture, Tel Aviv University [email protected] Ben Outhwaite University of Cambridge [email protected] Abstract A study of two documents from the Cairo Genizah, a vast repository of medieval Jewish writings recovered from a synagogue in Fusṭāṭ, Egypt, one hundred years ago, shows the importance of this archive for the history of medieval Yemen and, in particular, for the role that Yemen played in the Indian Ocean trade as both a commercial and administrative hub. The first document is a letter from Aden to Fusṭāṭ, dated 1133 CE, explaining the Aden Jewish community’s failure to raise funds to send to the heads of the Palestinian Gaonate in Egypt. It signals the decline of that venerable institution and the increasing independence of the Yemeni Jews. The second text is a legal document, produced by an Egyptian Jewish trader who intended to travel to Yemen, but who wished to ensure his wife was provided for in his absence. Both documents show the close ties between the Egyptian and Yemeni Jewish communities and the increasing commercial importance of Yemen to Egyptian traders. Keywords Cairo Genizah, history, India trade, al-Ǧuwwa, Hebrew, Judaeo- Arabic, marriage, Jewish leadership, legal contract, Aden, Fusṭāṭ. 1. Introduction The discovery of a vast store of manuscripts and early printed material in the Ben Ezra Synagogue in Fusṭāṭ at the end of the nineteenth century revolutionised the academic study of Judaism and provided a wealth of primary sources for the scrutiny of the Mediterranean world at large in the High Middle Ages and Early Modern period. -

Historical Studies (HIS) 1

Historical Studies (HIS) 1 HIS 594B. Egypt. (2 h) HISTORICAL STUDIES (HIS) This course provides an historical introduction to Egypt's Muslim society as the context within which minority Christian communities HIS 501. History of Christianity. (3 h) have practiced their faith. By traveling to the Arab Republic of Egypt, This course surveys the first through the 16th centuries. Attention is students will directly experience Muslim culture and religion as they given to the early Councils, the rise of the papacy, dissenting movements, investigate Egypt's rich religious heritage. The class will visit numerous and the development of the sacraments. Medieval studies include pharaonic, Christian, Muslim, and (historically) Jewish places of worship mysticism, church/state affiliations, and scholasticism. Reformation in the greater Cairo area and in Egypt's stunning archeological sites at issues survey the work of Luther, Zwingli, Calvin and the Radical the southern environs of Luxor. We will witness the grandeur of Islamic Reformers. civilization in Cairo's medieval mosques and modern monuments. We HIS 502. History of Christianity II. (3 h) will discuss the tumultuous history of Jews in Egypt while touring Cairo's This course surveys the 17th through the 20th centuries. Attention is historic Ben Ezra Synagogue. We will examine Christian monasticism given to the rise of modernism and its impact on philosophy, theology, in the place of its origin at the Wadi Natrun. Site visits to numerous ecclesiology and politics. Catholic studies focus on individuals such as Christian churches, including All Saints Anglican Church (with its Sor Juana de la Cruz, Teresa of Avila, Alfred Loisy, Pius IX, John XXII and Sudanese refugee congregation), will expose students to a diversity of Dorothy Day, and the impact of Liberation Theology. -

Land, Property Rights and Institutional Durability in Medieval Egypt

Land, Property Rights and Institutional Durability in Medieval Egypt Lisa Blaydes - Stanford University LSE-Stanford-Universidad de los Andes Conference on Long-Run Development in Latin America, London School of Economics and Political Science, 16-17 May 2018 Land, Property Rights and Institutional Durability in Medieval Egypt Lisa Blaydes∗ Associate Professor Department of Political Science Stanford University April 2018 Abstract Historical institutionalists have long been concerned with the conditions under which political institutions provoke their own processes of internal change. Using data on changing landholding patterns during the Mamluk Sultanate (1250-1517 CE), I demon- strate that land shifted from temporary and revocable land grants offered in exchange for service to Islamic religious endowments and hybridized land types, representing a transformation away from state authority over agricultural resources to more priva- tized forms of property control. Predation on collective state resources by individual mamluks | state actors themselves | was a negative externality associated with the foundational principle of the impermissibility of transferring mamluk status to one's sons. My characterization of mamluk political institutions provides an empirical il- lustration of a self-undermining equilibrium with implications for understanding how Middle Eastern political institutions differed from those in other world regions, partic- ularly medieval Europe. ∗Many thanks to Connor Kennedy, Shivonne Logan, Vivan Malkani and Kyle Van Rensselaer for out- standing research assistance. Scott Abramson, Gary Cox, David Laitin, Hans Lueders and Yuki Takagi provided helpful comments and assistance. 1 What explains institutional durability? An influential literature suggests that institu- tional equilibria can be indirectly strengthened or weakened by processes dynamically intro- duced by the institutions themselves (Greif and Laitin 2004). -

The Holy Family Inegypt

The Holy Family inEgypt 1 INTRODUCTION Egypt is the cradle of human civilization: a fact hardly Because the Egyptian people are the essential product contested among authoritative historians. But Egypt also of this “harmony in diversity”, “otherness” has become an enjoys a focal geo-political position, connecting Africa, Asia, integral component of their awareness, a basic constituent and Europe through the Mediterranean Sea. On its land, of their national and cultural identity. This characteristic has migrations of people, traditions, philosophies and religious yielded one important result: Egypt was, and still is, the land beliefs succeeded each other for thousands of years. Evidence of refuge in the widest sense of the word, a place of tolerance of this succession is still visible in the accumulation of and dialogue for peoples, races, cultures and religions. monuments and sites attesting to a uniquely comprehensive On this land of Egypt, the first voice proclaiming the cultural heritage. Indeed, one of the phenomena which Oneness of God rang out in the 14th century B.C. through shaped Egypt s distinctive identity, and explains its pervasive ’ Akhnaton’s monotheistic creed. Moses and Jesus lived in this influence on the then known world, was a dynamism that same land. Later, Islam entered without conflict. accommodated and re-formulated these successive cultures into one homogenous and harmonious Egyptian canvas. Egypt is one civilization woven of many strands, threaded by successive and intertwining eras; and of these, the most luminous are, without doubt, the Pharaonic, the Graeco- Roman, the Coptic Christian, and the Islamic eras. 3 The advent of the Holy prediction of the effect the Family to Egypt, seeking holy Infant was to have on refuge, is an event of the Egypt and the Egyptians: utmost significance in our “Behold, the Lord rides on dear country’s long, long a swift cloud, and will come history. -

Exhibit Shows How Christians, Muslims, and Jews Created a Vibrant Society in Medieval Cairo a New Exhibition at the University

January 13, 2015 Contact: Emily Teeter 773 702 1062 [email protected] Susie Allen [email protected] 773 702-4009 Exhibit Shows How Christians, Muslims, and Jews created a Vibrant Society in Medieval Cairo A new exhibition at the University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute Museum will offer a glimpse into everyday life in a lively, multicultural city in ancient Egypt. “A Cosmopolitan City: Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Old Cairo” features many objects that have never been displayed in the museum before and shows how people of different faiths interacted to create a vibrant society. The exhibit is on view from February 17 through September 13, 2015. The exhibit sheds light on Egypt in the time between the pharaohs and the modern city, roughly 650–1170 AD, when the main population lived in the area known as Fustat, located in today’s southern Cairo. Fustat was established in 641 by the first Muslim ruler of Egypt, ‘Amr Ibn al-‘As. His administration included Christians, whose community was established there some 600 years before, and Jews, who had settlements in the Nile Valley for over a millennium. "So much is known about Fustat from written sources,” said Jack Green, Chief Curator of the Oriental Institute Museum. “This exhibit also presents some the material possessions of the community, providing insights into the everyday lives of the people who lived in this bustling city.” Visitors to the exhibit will explore how Old Cairo’s communities lived together and melded their traditions to create a multicultural society. The neighborhoods of Fustat were populated by people from a patchwork of religious and ethnic communities, including native Egyptians and immigrants from Arabia, North Africa, and other regions of the Middle East. -

Lecture Transcript: Karaites in Egypt

Lecture Transcript: Karaites in Egypt: The Preservation of Jewish-Egyptian Heritage Sunday, September 13, 2020 Louise Bertini: Hello, everyone, and good afternoon or good evening, depending on where you are joining us from. And welcome to our special September lecture, titled, "Karaites in Egypt: The Preservation of Egyptian-Jewish Heritage." I'm Dr. Louise Bertini, the executive director of the American Research Center in Egypt. ARCE is a nonprofit organization composed of educational and cultural institutions, professional scholars and members alike whose mission is to support research on all aspects of Egyptian history and culture, foster a broader knowledge about Egypt among the general public and to strengthen American-Egyptian cultural ties. I want to extend a special welcome to any ARCE members who are joining us today, and if you are not already a member, I encourage you to visit our website, arce.org, where you can find further information on how to join. I want to direct your attention to the Q and A button, to which you can pose questions at the end of the lecture. Today's lecture is also done in partnership with the Drop of Milk Association, whose mission is to promote interfaith tolerance through the preservation of Egyptian-Jewish heritage and promotion of its history through cultural events. I will shortly be introducing Magda Haroun, the head of the Egyptian-Jewish community in Cairo. In 2019, ARCE, in partnership with the Drop of Milk Association, was awarded a grant from the US Ambassadors Fund for Cultural Preservation to document the remaining areas of the historic Bassatine Cemetery, as well as pilot a conservation project in the two burial grounds belonging to the Menasha and Lichaa families, who are prominent members of Egypt's Karaite community. -

Threshold to the Sacred: the Ark Door of Cairo's Ben Ezra Synagogue

For Immediate Release Contact: Michael Kaminer, 212‐260‐9733 [email protected] MEDIEVAL TORAH ARK DOOR FROM CAIRO’S BEN‐EZRA SYNAGOGUE OFFERS DOORWAY INTO JEWISH CAIRO’S REMARKABLE PAST NOW ON VIEW AT YESHIVA UNIVERSITY MUSEUM WHAT: Threshold to the Sacred: The Ark Door of Cairo’s Ben Ezra Synagogue WHEN: October 27, 2013 – February 23, 2014 WHERE: Yeshiva University Museum, 15 W. 16th Street, NYC, 212‐294‐8330 COST: Adults: $8; seniors and students: $6. Free for members and children under 5 WEB: http://yumuseum.tumblr.com/ArkDoor or www.yumuseum.org “Threshold to the Sacred: The Ark Door of Cairo’s Ben Ezra Synagogue” Includes Rare Manuscripts by Philosopher and Physician Moses Maimonides and Poet and Philosopher Judah Halevi Medieval Treasure Re‐Discovered in Florida in 1990s New York City, October 24 2013 – An exquisite artifact from a celebrated Cairo synagogue sheds light on daily life in the medieval Mediterranean – and illuminates the city’s remarkable pluralistic past – in an extraordinary new exhibition at Yeshiva University Museum. Yeshiva University Museum, at the Center for Jewish History (15 West 16th Street) near Union Square in New York City, explores and interprets the artistic and cultural experience of Jewish life. Threshold to the Sacred: The Ark Door of Cairo's Ben Ezra Synagogue focuses on a work of beauty and historical significance: an intricately carved and inscribed wood panel that formed part of the door to the ark 8holding the Torah scrolls in the Ben Ezra Synagogue of Old Cairo. The ark door, which dates to the 11th century but was re‐decorated over centuries of use, is jointly owned by Yeshiva University Museum and the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore. -

Muslim-Jewish Relations in the Middle Islamic Period

© 2017, V&R unipress GmbH, Göttingen ISBN Print: 9783847107927 – ISBN E-Book: 9783847007920 Mamluk Studies Volume 16 Edited by Stephan Conermann and Bethany J. Walker Editorial Board: Thomas Bauer (Münster, Germany), Albrecht Fuess (Marburg, Germany), ThomasHerzog (Bern, Switzerland), Konrad Hirschler (London, Great Britain),Anna Paulina Lewicka (Warsaw, Poland), Linda Northrup (Toronto, Canada), Jo VanSteenbergen (Gent, Belgium) © 2017, V&R unipress GmbH, Göttingen ISBN Print: 9783847107927 – ISBN E-Book: 9783847007920 Stephan Conermann (ed.) Muslim-Jewish Relations in the Middle Islamic Period Jews in the Ayyubid and Mamluk Sultanates (1171–1517) V&Runipress Bonn University Press © 2017, V&R unipress GmbH, Göttingen ISBN Print: 9783847107927 – ISBN E-Book: 9783847007920 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available online: http://dnb.d-nb.de. ISSN 2198-5375 ISBN 978-3-8470-0792-0 You can find alternative editions of this book and additional material on our website: www.v-r.de Publications of Bonn University Press are published by V&R unipress GmbH. Sponsored by the Annemarie Schimmel College ªHistory and Society during the Mamluk Era, 1250±1517º. © 2017, V&R unipress GmbH, Robert-Bosch-Breite 6, 37079 Göttingen, Germany / www.v-r.de All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior written permission from the publisher. Cover image: Ben Ezra Synagogue, Cairo, Egypt (photographer: Faris Knight, 10/12/2011). © 2017, V&R unipress GmbH, Göttingen ISBN Print: 9783847107927 – ISBN E-Book: 9783847007920 Contents Stephan Conermann Introduction................................. -

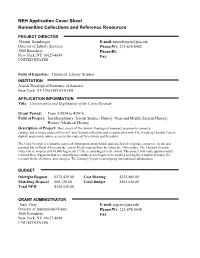

NEH Application Cover Sheet Humanities Collections and Reference Resources

NEH Application Cover Sheet Humanities Collections and Reference Resources PROJECT DIRECTOR Naomi Steinberger E-mail:[email protected] Director of Library Services Phone(W): 212-678-8982 3080 Broadway Phone(H): New York, NY 10027-4649 Fax: UNITED STATES Field of Expertise: Technical: Library Science INSTITUTION Jewish Theological Seminary of America New York, NY UNITED STATES APPLICATION INFORMATION Title: Conservation and Digitization of the Cairo Genizah Grant Period: From 5/2014 to 4/2016 Field of Project: Interdisciplinary: Jewish Studies; History: Near and Middle Eastern History; History: Medieval History Description of Project: The Library of The Jewish Theological Seminary proposes to conserve, catalog, and re-house material from its Cairo Genizah collection and, in partnership with The Friedberg Genizah Project, digitize and provide online access to this material for scholars and the public. The Cairo Genizah is a valuable source of information about Jewish and non-Jewish religious, economic, social, and personal life in North Africa and the eastern Mediterranean from the 9th to the 19th century. The Library's Genizah collection is comprised of 43,000 fragments ??? the second-largest in the world. This project will make approximately 6,000 of these fragments that are currently unreadable or too fragile to be handled and digitized widely available for research for the first time, and complete The Library???s part in an ongoing international collaboration. BUDGET Outright Request $272,429.00 Cost Sharing $222,469.00 Matching Request $68,120.00 Total Budget $563,018.00 Total NEH $340,549.00 GRANT ADMINISTRATOR Josie Gray E-mail:[email protected] Director of Institutional Grants Phone(W): 212-678-8048 3080 Broadway Fax: New York, NY 10027-4649 UNITED STATES The Library of The Jewish Theological Seminary Application to NEH Division of Preservation and Access, HCRR Program, July 2013 Implementation Grant for Conservation and Digitization of the Cairo Genizah 1.