Chapter One: 1920-1929

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Vertical Files Anderson Reading Room Center for Southwest Research Zimmerman Library

“A” – biographical Abiquiu, NM GUIDE TO THE GENERAL VERTICAL FILES ANDERSON READING ROOM CENTER FOR SOUTHWEST RESEARCH ZIMMERMAN LIBRARY (See UNM Archives Vertical Files http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmuunmverticalfiles.xml) FOLDER HEADINGS “A” – biographical Alpha folders contain clippings about various misc. individuals, artists, writers, etc, whose names begin with “A.” Alpha folders exist for most letters of the alphabet. Abbey, Edward – author Abeita, Jim – artist – Navajo Abell, Bertha M. – first Anglo born near Albuquerque Abeyta / Abeita – biographical information of people with this surname Abeyta, Tony – painter - Navajo Abiquiu, NM – General – Catholic – Christ in the Desert Monastery – Dam and Reservoir Abo Pass - history. See also Salinas National Monument Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Afghanistan War – NM – See also Iraq War Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Abrams, Jonathan – art collector Abreu, Margaret Silva – author: Hispanic, folklore, foods Abruzzo, Ben – balloonist. See also Ballooning, Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta Acequias – ditches (canoas, ground wáter, surface wáter, puming, water rights (See also Land Grants; Rio Grande Valley; Water; and Santa Fe - Acequia Madre) Acequias – Albuquerque, map 2005-2006 – ditch system in city Acequias – Colorado (San Luis) Ackerman, Mae N. – Masonic leader Acoma Pueblo - Sky City. See also Indian gaming. See also Pueblos – General; and Onate, Juan de Acuff, Mark – newspaper editor – NM Independent and -

NEA-Annual-Report-1980.Pdf

National Endowment for the Arts National Endowment for the Arts Washington, D.C. 20506 Dear Mr. President: I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Council on the Arts for the Fiscal Year ended September 30, 1980. Respectfully, Livingston L. Biddle, Jr. Chairman The President The White House Washington, D.C. February 1981 Contents Chairman’s Statement 2 The Agency and Its Functions 4 National Council on the Arts 5 Programs 6 Deputy Chairman’s Statement 8 Dance 10 Design Arts 32 Expansion Arts 52 Folk Arts 88 Inter-Arts 104 Literature 118 Media Arts: Film/Radio/Television 140 Museum 168 Music 200 Opera-Musical Theater 238 Program Coordination 252 Theater 256 Visual Arts 276 Policy and Planning 316 Deputy Chairman’s Statement 318 Challenge Grants 320 Endowment Fellows 331 Research 334 Special Constituencies 338 Office for Partnership 344 Artists in Education 346 Partnership Coordination 352 State Programs 358 Financial Summary 365 History of Authorizations and Appropriations 366 Chairman’s Statement The Dream... The Reality "The arts have a central, fundamental impor In the 15 years since 1965, the arts have begun tance to our daily lives." When those phrases to flourish all across our country, as the were presented to the Congress in 1963--the illustrations on the accompanying pages make year I came to Washington to work for Senator clear. In all of this the National Endowment Claiborne Pell and began preparing legislation serves as a vital catalyst, with states and to establish a federal arts program--they were communities, with great numbers of philanthro far more rhetorical than expressive of a national pic sources. -

NEA-Annual-Report-1992.Pdf

N A N A L E ENT S NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR~THE ARTS 1992, ANNUAL REPORT NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR!y’THE ARTS The Federal agency that supports the Dear Mr. President: visual, literary and pe~orming arts to I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report benefit all A mericans of the National Endowment for the Arts for the fiscal year ended September 30, 1992. Respectfully, Arts in Education Challenge &Advancement Dance Aria M. Steele Design Arts Acting Senior Deputy Chairman Expansion Arts Folk Arts International Literature The President Local Arts Agencies The White House Media Arts Washington, D.C. Museum Music April 1993 Opera-Musical Theater Presenting & Commissioning State & Regional Theater Visual Arts The Nancy Hanks Center 1100 Pennsylvania Ave. NW Washington. DC 20506 202/682-5400 6 The Arts Endowment in Brief The National Council on the Arts PROGRAMS 14 Dance 32 Design Arts 44 Expansion Arts 68 Folk Arts 82 Literature 96 Media Arts II2. Museum I46 Music I94 Opera-Musical Theater ZlO Presenting & Commissioning Theater zSZ Visual Arts ~en~ PUBLIC PARTNERSHIP z96 Arts in Education 308 Local Arts Agencies State & Regional 3z4 Underserved Communities Set-Aside POLICY, PLANNING, RESEARCH & BUDGET 338 International 346 Arts Administration Fallows 348 Research 35o Special Constituencies OVERVIEW PANELS AND FINANCIAL SUMMARIES 354 1992 Overview Panels 360 Financial Summary 36I Histos~f Authorizations and 366~redi~ At the "Parabolic Bench" outside a South Bronx school, a child discovers aspects of sound -- for instance, that it can be stopped with the wave of a hand. Sonic architects Bill & Mary Buchen designed this "Sound Playground" with help from the Design Arts Program in the form of one of the 4,141 grants that the Arts Endowment awarded in FY 1992. -

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

NPS Form 10-900-b OMB No. 1024-0018 (March 1992) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. X New Submission _ Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Historic Theaters and Opera Houses of Kansas B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) The Historical Development of Public Entertainment in Kansas, 18 54-1955 C. Form Prepared by name/title Elizabeth Rosin. Partner, assisted by Dale Nimz, Ph.D., Historian and Kristen Ottesen. Architectural Historian company Historic Preservation Services. LLC street & number 323 West 8th Street, Suite 112___________ telephones 16-221-5133 city or town Kansas City___________________________________ state MO zip code 64105 D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation. -

HISTORIC HOUSES in the DNA

HISTORIC HOUSES in the DNA Albuquerque’s DOWNTOWN Neighborhoods Association HISTORIC HOUSES in the DNA Albuquerque’s DOWNTOWN Neighborhoods Association This book is published by DNA with the support of a Bernalillo County Neighborhood Outreach Grant Book layout, design and photography by Chan Graham The text has been taken from historic sources. © 2014 Downtown Neighborhoods Association CONTENTS Introduction and Acknowledgments Page 2 Remembering Susan Dewitt Page 3 Historic Properties in the DNA Pages 4-5 Preface Page 5 A History of the Dna Page 6 Houses in the Fourth Ward Historic District Pages 7-21 Houses in the Eighth Street Forrester Historic District Pages 22-29 Houses in the Manzano Court Historic District Pages 30-31 Houses in the Watson Historic District Pages 32-37 Houses in the Orilla de la Acequia Historic District Pages 38-39 Houses & Buildings Outside of Historic Districts Pages 40-43 1 Introduction and Acknowledgments The DNA HISTORY PROJECT The DNA History Project began in the Fall of 2012 when the Budget Committee of the Downtown Neigh - borhoods Association (DNA) decided to apply for one of the Bernalillo County Neighborhood Outreach Grants. We discussed, at length, what should be included in the grant application and what the name of our project should be. The DNA HISTORY PROJECT was chosen as the project name and our grant application was submitted. We were successful in receiving one of the larger grants. For the first phase of the project we took pictures of people in front of their homes. The images are up, on-line, as history.abqDNA.com . -

Rio Puerco Resource Management Draft Plan & Environmental Impact Statement

Rio Puerco Resource Management Draft Plan & Environmental Impact Statement Volume III August 2012 United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Albuquerque District Rio Puerco Field Office TABLE OF CONTENTS A CULTURAL RESOURCES ON NON-BLM LANDS LISTED ON THE NRHP ........ A-1 B DESCRIPTION OF GRAZING ALLOTMENTS BY ACREAGE AND AUMS ......... B-1 C EXAMPLES OF PRESCRIBED GRAZING SYSTEMS .............................................. C-1 C.1 Rest-Rotation Grazing ................................................................................................ C-1 C.2 Deferred Rotation Grazing .......................................................................................... C-1 C.3 Deferred Grazing ........................................................................................................ C-1 C.4 Alternate Grazing ........................................................................................................ C-1 C.5 Short-Duration, High-Intensity Grazing ..................................................................... C-2 D RANGELAND IMPROVEMENTS ............................................................................... D-1 D.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................. D-1 D.2 Structural Improvements ............................................................................................. D-1 D.2.1 Fences .............................................................................................................................. -

Pueblo Deco Tour

Art Deco Society of New Mexico Albuquerque Tricentennial Pueblo Deco Tour KiMo Theater, 1926-27, Carl Boller & Robert Boller, Central Avenue @ 5th Street SW, Albuquerque, New Mexico. Photograph: Copyright Carla Breeze, 2005 Instruction for using self-guided Albuquerque Art Deco Tour. Print guide, fold all pages in half vertically. Staple along spine of fold. Tour guide is designed to be printed front & back of paper, Page1 printed on one side, Page 2 on the back of Page 1, etc. Begin tour in Albuquerque’s Central Business District, at the NE corner of Central Avenue & 5th Street. Follow directions for walking KiMo Theater, 1926-27, Carl Boller & Robert Boller, Central Avenue @ 5th Street SW, from KiMo to other buildings in Central Business District. The remainder Albuquerque, New Mexico. Photograph: Copyright Carla Breeze, 2005 of buildings on tour are located further east along Central Avenue and Lomas. It is much easier to see buildings if on foot or bicycle. Interiors of some buildings may be accessible, but call ahead fi rst. A guided tour will be offered September 3, 2005 led by ar- chitectural photographer, Carla Breeze, author of Pueblo Deco, and most recently, American Art Deco: Architecture and Regionalism. Albuquerque Tricentennial Pueblo Deco Tour is sponsored by Albuquerque Cultural Af- fairs and the Art Deco Society of New Mexico. ADSNM would like to thank Don Wagy for logo design and Mil- lie Santillanes, Director of the City of Albuquerque’s Cultural Affairs De- partment. KiMo Theater, detail of faience tiles in foyer. Photograph: Copyright Carla Breeze, 2005 Begin the self guided tour by parking in the public parking ga- rage behind the KiMo Theater, on 5th Street & Copper, the SE corner. -

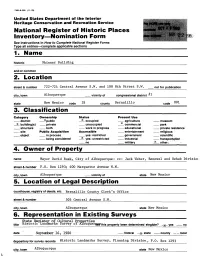

National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form 1

FHR-8-300 (11-78) United States Department of the Interior Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections________________ 1. Name historic Skinner Building and/or common 2. Location street & number 722-724 Central Avenue S.W. and 108 8th Street S.W. not for publication city, town Albuquerque vicinity of congressional district state New Mexico cocje 35 county Bernalillo code 001 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district xpublic x occupied agriculture museum x building(s) private unoccupied x commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process yes: restricted government scientific being considered x yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military x other- 4. Owner of Property name Mayor David Rusk, City of Albuquerque: cc: Jack Weber, Renewal and Rehab Divisioi street & number P.O. Box 1293; 400 Marquette Avenue N.W. city, town Albuquerque vicinity of state New Mexico 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Bernalillo County Clerk f s Office street & number 505 Central Avenue S.W. city, town Albuquerque state New Mexico 6. Representation in Existing Surveys State Biegister of Cultural Properties title Historic Landmarks Survey of Albuquer>uquerflajetnjs property been determined elegible? x Ves —_ no date September 16, 1980 federal __x- state __county __ local depository for survey records Historic Landmarks Survey, Planning Division, P.O. Box 1293 city, town Albuquerque state New Mexico 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent deteriorated unaltered x original site x good ruins X altered moved date fair unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance A small and well-detailed Art Deco commercial building, the J.A. -

NEW MEXICO HISTORIC PRESERVATION: a Plan for the Year 2001

NEW MEXICO HISTORIC PRESERVATION: A Plan for the Year 2001 La Capilla de Estaca. A gathering of residents and friends viewing historic photographs as part of the writing of the historic context and State Register nomination for the Capilla. Prepared by The New Mexico State Historic Preservation Division Office of Cultural Affairs 228 East Palace Avenue Santa Fe, NM 87501 Phone: (505) 827-6320 Fax: 505-827-6338 1998 New Mexico Historic Preservation: A Plan for the Year 2001 1 New Mexico Historic Preservation: A Plan for the Year 2001 2 Acknowledgments New Mexico Historic Preservation Division (State Historic Preservation Office) The planning process that resulted in this plan has included the participation of so many people it is The Cultural Properties Review Committee and the State Historic Preservation Office staff have been indispensable impossible to acknowledge you all. We are particularly indebted to those of you who expressed your in their contribution of ideas, help and participation in the forum and surveys, and preparation of materials and ideas about historic preservation in the public participation portions of the plan-in the forum (100 critiques of the draft version of this plan. The staff will be responsible for the coordination of the next state plan and, attendees) and the survey (624 respondents). We also appreciate your participation in the review and in part, for the implementation of this plan. The staff welcomes comments and inquiries from the public regarding this plan, as well as specific historic preservation issues in New Mexico. comment of the first draft of this plan. Officer of Cultural Affairs - J.Edson Way, Ph.D. -

A Curriculum About Route 66 in New Mexico Acknowledgements

Road Trips A Curriculum about Route 66 in New Mexico Acknowledgements Sponsors – New Mexico Department of Transportation New Mexico Department of Cultural Affairs Partners – New Mexico History Museum ~ a division of the Department of Cultural Affairs Statewide Outreach Department ~ a division of the Department of Cultural Affairs Exhibit Team Project Directors ~ Shelley Thompson and Frances Levine, Ph.D. Project Manager ~ Kimberly Mann Lead Educator ~ Jamie Brytowski Curriculum ~ Beth Maloney Exhibition and Graphic Design ~ Discovery Exhibits We wish to thank the following people and institutions for their contributions: Palace of the Governors, Nancy Tucker, Joe Sonderman, Center for Southwest Research, Museum of New Mexico Press, Tom Willis and his staff, Santa Fe Vintage Car Club, Buddy Roybal, Ed Baca, Jack Sullivan, Jim Ross, James Hart Photography, Todd Anderson, Subia, Inc., Erica Tapia, Andrew Houghton, and Nicholas Olrik 2 Table of Contents Overview . 4 Background Information . 5 Suggested pre-visit activities . 10 Lesson Plans for 4th Grade . 12 Lesson Plans for 7th Grade . 23 Lesson Plans for 12th Grade . 33 Vocabulary List . 43 Bibliography of Print and On-line Resources . 45 List of Historic places along Route 66 in New Mexico . 50 Curriculum Evaluation . 52 3 Overview Goals of Our Project Road Trips The lessons in this curriculum are designed to support a visit to the Road Trips exhibition on the Van of Enchantment. These The exhibition explores the history of Route 66 in New Mexico lessons use primary and secondary sources—photographs, and what impact this important road has had on the people and postcards, interviews, written material, images and maps—as the communities of New Mexico. -

Case Studies of the People and Places of Route 66

Technical Report, Volume ii Tales from the mother Road: case Studies of the people and places of Route 66 A study conducted by Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in collaboration with the National Park Service Route 66 Corridor Preservation Program and World Monuments Fund Study funded by American Express TECHNICAL REPORT, VOLUME II Tales from the Mother Road: Case Studies of the People and Places of Route 66 A study conducted by Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in collaboration with the National Park Service Route 66 Corridor Preservation Program and World Monuments Fund Study funded by American Express Center for Urban Policy Research Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey New Brunswick, New Jersey June 2011 AUTHORS David Listokin and David Stanek Kaitlynn Davis with Michelle Riley Andrea Ryan Sarah Collins Samantha Swerdloff Jedediah Drolet other participating researchers include Carissa Johnson Bing Wang Joshua Jensen Center for Urban Policy Research Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey New Brunswick, New Jersey ISBN-10 0-9841732-5-0 ISBN-13 978-0-9841732-5-9 This report in its entirety may be freely circulated; however content may not be reproduced independently without the permission of Rutgers, the National Park Service, and World Monuments Fund. Table of Contents Technical Report, Volume II INTRODUCTION TO ROUTE 66 AND TALES FROM THE MOTHER ROAD ................................................................................................ 6 CHAPTER ONE History of Route 66 and Contemporary Efforts to Preserve the Mother Road .............................................................. 21 CHAPTER TWO Tales from the Mother Road: Introduction ................................................................................................................... -

National Register of Historic Places

NFS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department off the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory — Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries— complete applicable sections _______________ 1. Name historic Hi 1 ton Hotel and/or common Plaza Hotel; La Posada de Albuquerque 2. Location street & number 125 Second St. N.W. not for publication city, town Albuquerque vicinity of state New Mexico code 35 county Bernalillo code 001 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public x occupied agriculture museum x building(s) x private unoccupied x commercial park structure both x work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process X yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation X N/A no military other: 4. Owner of Property name Thomas Childers, Southwestern Resorts street & number p.p. Box 5538 city, town Beverly Hills vicinity of state California 90210 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Bernalillo County Records street & number 505 Central N.W. city, town Albuquerque state New Mexico 6. Representation in Existing Surveys__________ ,. Albuquerque title Historic Landmarks Survey of has this property been determined eligible? __yes _x_no date November, 1978; November, 1983 federal state county x local depository for survey records Community & Economic Development Dept. 600 2nd St. N.W city, town Albuquerque state New Mexico 7. Description Condition Check one Check one __ excellent __ deteriorated __ unaltered X original site goad , f,.j __ ruins _X_ altered __ moved date ';^%» __ unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance The old Hilton Hotel stands at the southwest corner of the intersection of Second Street and Copper Avenue in Downtown Albuquerque, a half-block north of Central Avenue, the city's major thoroughfare.