Eric Tomlinson - Recording Engineer Eric Tomlinson Recording Engineer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bomb Scare Clears Kirkbride Therapy for Accident Victim "If It's on Camous and It's by KEN MAMMARELLA Threat Procedure of Leaving the Suspected Karen Seitz

Bulk Rate U.S. Postage PAID ff>ermit No.320 Newark, DE. Friday. April6. 1979 By DEBORAH PETIT MIDDLETOWN, Pa.,- With a potential core melt-down now greatly reduced, officials at the Three Mile Island Nuclear Reactor Site are turning their attention to the pro blems of cleaning up radioactive substances left by the re cent reactor accident. Upon analysis of the extent of damage incurred in the mishap and the level of radioactive contamination left in the reactor, experts will determine the fate of the Three Mile site. An evaluation of the costs involved will leave the officials with the options of either refurbishing or decommissioning the plant. Both of which would require large amounts of time and money. · The projected time for complete decontamination of the reactor now stands at least one to two years. Additional time beyond ~hat estimate would be required to bring the plant back to operational levels. Cost estimates for the refurbishment of the reactor can not be determined from present data. The costs and time involved in decommissioning the site, however, can be more accurately determined from previous studies done by the Nuclear Regulatory Commis sion (NRC). Most data points to a dismantling cost estimate of roughly Review photo by Andy Cline 5 percent to 10 percent of the original construction costs. "THEY'VE PUSHED THE PANIC BUTTON as HAROLD DENTON, Director of the NRC's of The NRC conducted a study of the Trojan reactor site in far as I'm concerned," Mitzi Krause said of fice of Nuclear Reactor Regulation, and Oregon and came up with a dismantling cost in 1978 of just the nuclear accident on near by Three Mile NRC spokesman Joseph Fouchard {left) aid- over $42 million to level the plant. -

Gonna Fly Now Theme from Rocky for Saxophone Quartet Sheet Music

Gonna Fly Now Theme From Rocky For Saxophone Quartet Sheet Music Download gonna fly now theme from rocky for saxophone quartet sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 1 pages partial preview of gonna fly now theme from rocky for saxophone quartet sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 3411 times and last read at 2021-09-25 02:51:20. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of gonna fly now theme from rocky for saxophone quartet you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Piano Solo Ensemble: Mixed Level: Early Intermediate [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Gonna Fly Now Theme From Rocky Saxophone Quartet Gonna Fly Now Theme From Rocky Saxophone Quartet sheet music has been read 4302 times. Gonna fly now theme from rocky saxophone quartet arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-24 11:17:12. [ Read More ] Gonna Fly Now Theme From Rocky For String Quartet Gonna Fly Now Theme From Rocky For String Quartet sheet music has been read 3807 times. Gonna fly now theme from rocky for string quartet arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-24 16:26:01. [ Read More ] Gonna Fly Now Theme From Rocky String Quartet Gonna Fly Now Theme From Rocky String Quartet sheet music has been read 3565 times. Gonna fly now theme from rocky string quartet arrangement is for Intermediate level. -

B R I a N K I N G M U S I C I N D U S T R Y P R O F E S S I O N a L M U S I C I a N - C O M P O S E R - P R O D U C E R

B R I A N K I N G M U S I C I N D U S T R Y P R O F E S S I O N A L M U S I C I A N - C O M P O S E R - P R O D U C E R Brian’s profile encompasses a wide range of experience in music education and the entertainment industry; in music, BLUE WALL STUDIO - BKM | 1986 -PRESENT film, television, theater and radio. More than 300 live & recorded performances Diverse range of Artists & Musical Styles UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA Music for Media in NYC, Atlanta, L.A. & Paris For more information; www.bluewallstudio.com • As an administrator, professor and collaborator with USC working with many award-winning faculty and artists, PRODUCTION CREDITS - PARTIAL LIST including Michael Patterson, animation and digital arts, Medeski, Martin and Wood National Medal of Arts recipient, composer, Morton Johnny O’Neil Trio Lauridsen, celebrated filmmaker, founder of Lucasfilm and the subdudes (w/Bonnie Raitt) ILM, George Lucas, and his team at the Skywalker Ranch. The B- 52s Jerry Marotta Joseph Arthur • In music education, composition and sound, with a strong The Indigo Girls focus on establishing relations with industry professionals, R.E.M. including 13-time Oscar nominee, Thomas Newman, and 5- Alan Broadbent time nominee, Dennis Sands - relationships leading to PS Jonah internships in L.A. and fundraising projects with ASCAP, Caroline Aiken BMI, the RMALA and the Musician’s Union local 47. Kristen Hall Michelle Malone & Drag The River Melissa Manchester • In a leadership role, as program director, recruitment Jimmy Webb outcomes aligned with career success for graduates Col. -

Christopher Young: El Simbiòtic Házael González

Bandes de so Christopher Young: el simbiòtic Házael González vui dirigirem la nostra mi A rada sobre un compositor amb un nom que sempre ens sona i que poca gent podrá identificar amb un treball que no siguí fantastic o terrorífíc quant a temàtica o a qualitats. Ens referím, és ciar, a Chris topher Young, de qui ara s'aca- ba d'estrenar ni més ni menys que Spider-Man 3 (Sam Raimi, 2007): en aquesta pel-licula, l'Home Aranya s'enfronta a un èsser extraterrestre que té pro- pietats simbiòtiques respecte del eos a qué s'afegeix, és a dir, que du a terme una mena de fusió Í amplifica tant els seus propís poders com els del seu portador. I això, justament, és el que ha fet Young aquesta ve gada: perqué, si ho recordeu, les altres dues parts anteriors (Spider-Man, 2002, i Spider- Man 2, 2004) portaven música de Danny Elfman (encara que a la segona part, Christopher Young ja hi havía parti at 1600, Dwíght H. Little, 1997), Hard Rain (Mikael cipât afegint-h¡ dues petites peces addícionals), un Salomon, 1998), Leyenda Urbana (Urban Legend, veli amie del director que va fer una feina mes que Jamie Blanks, 1998), La Trampa (Entrapment, Jon destacada; ara, Young hà hagut de recollir moites Amiel, 1999), o Jóvenes Prodigiosos (Wonder Boys, de les composícions elfmanianes (per no parlar de Curtís Hanson, 2000). I desprès, continuant amb co les cançonetes afegídes) i començar a recosír i reta ses com Operación Swordfish (Swordfish, Dominic llar, donant-h¡ un nou i personal toc. -

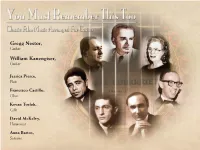

Gregg Nestor, William Kanengiser

Gregg Nestor, Guitar William Kanengiser, Guitar Jessica Pierce, Flute Francisco Castillo, Oboe Kevan Torfeh, Cello David McKelvy, Harmonica Anna Bartos, Soprano Executive Album Producers for BSX Records: Ford A. Thaxton and Mark Banning Album Produced by Gregg Nestor Guitar Arrangements by Gregg Nestor Tracks 1-5 and 12-16 Recorded at Penguin Recording, Eagle Rock, CA Engineer: John Strother Tracks 6-11 Recorded at Villa di Fontani, Lake View Terrace, CA Engineers: Jonathan Marcus, Benjamin Maas Digitally Edited and Mastered by Jonathan Marcus, Orpharian Recordings Album Art Direction: Mark Banning Mr. Nestor’s Guitars by Martin Fleeson, 1981 José Ramirez, 1984 & Sérgio Abreu, 1993 Mr. Kanengiser’s Guitar by Miguel Rodriguez, 1977 Special Thanks to the composer’s estates for access to the original scores for this project. BSX Records wishes to thank Gregg Nestor, Jon Burlingame, Mike Joffe and Frank K. DeWald for his invaluable contribution and oversight to the accuracy of the CD booklet. For Ilaine Pollack well-tempered instrument - cannot be tuned for all keys assuredness of its melody foreshadow the seriousness simultaneously, each key change was recorded by the with which this “concert composer” would approach duo sectionally, then combined. Virtuosic glissando and film. pizzicato effects complement Gold's main theme, a jaunty, kaleidoscopic waltz whose suggestion of a Like Korngold, Miklós Rózsa found inspiration in later merry-go-round is purely intentional. years by uniting both sides of his “Double Life” – the title of his autobiography – in a concert work inspired by his The fanfare-like opening of Alfred Newman’s ALL film music. Just as Korngold had incorporated themes ABOUT EVE (1950), adapted from the main title, pulls us from Warner Bros. -

Lister); an American Folk Rhapsody Deutschmeister Kapelle/JULIUS HERRMANN; Band of the Welsh Guards/Cap

Guild GmbH Guild -Light Catalogue Bärenholzstrasse 8, 8537 Nussbaumen, Switzerland Tel: +41 52 742 85 00 - e-mail: [email protected] CD-No. Title Track/Composer Artists GLCD 5101 An Introduction Gateway To The West (Farnon); Going For A Ride (Torch); With A Song In My Heart QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT FARNON; SIDNEY TORCH AND (Rodgers, Hart); Heykens' Serenade (Heykens, arr. Goodwin); Martinique (Warren); HIS ORCHESTRA; ANDRE KOSTELANETZ & HIS ORCHESTRA; RON GOODWIN Skyscraper Fantasy (Phillips); Dance Of The Spanish Onion (Rose); Out Of This & HIS ORCHESTRA; RAY MARTIN & HIS ORCHESTRA; CHARLES WILLIAMS & World - theme from the film (Arlen, Mercer); Paris To Piccadilly (Busby, Hurran); HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; DAVID ROSE & HIS ORCHESTRA; MANTOVANI & Festive Days (Ancliffe); Ha'penny Breeze - theme from the film (Green); Tropical HIS ORCHESTRA; L'ORCHESTRE DEVEREAUX/GEORGES DEVEREAUX; (Gould); Puffin' Billy (White); First Rhapsody (Melachrino); Fantasie Impromptu in C LONDON PROMENADE ORCHESTRA/ WALTER COLLINS; PHILIP GREEN & HIS Sharp Minor (Chopin, arr. Farnon); London Bridge March (Coates); Mock Turtles ORCHESTRA; MORTON GOULD & HIS ORCHESTRA; DANISH STATE RADIO (Morley); To A Wild Rose (MacDowell, arr. Peter Yorke); Plink, Plank, Plunk! ORCHESTRA/HUBERT CLIFFORD; MELACHRINO ORCHESTRA/GEORGE (Anderson); Jamaican Rhumba (Benjamin, arr. Percy Faith); Vision in Velvet MELACHRINO; KINGSWAY SO/CAMARATA; NEW LIGHT SYMPHONY (Duncan); Grand Canyon (van der Linden); Dancing Princess (Hart, Layman, arr. ORCHESTRA/JOSEPH LEWIS; QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT Young); Dainty Lady (Peter); Bandstand ('Frescoes' Suite) (Haydn Wood) FARNON; PETER YORKE & HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; LEROY ANDERSON & HIS 'POPS' CONCERT ORCHESTRA; PERCY FAITH & HIS ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/JACK LEON; DOLF VAN DER LINDEN & HIS METROPOLE ORCHESTRA; FRANK CHACKSFIELD & HIS ORCHESTRA; REGINALD KING & HIS LIGHT ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/SERGE KRISH GLCD 5102 1940's Music In The Air (Lloyd, arr. -

Click to Download

v8n4 covers.qxd 5/13/03 1:58 PM Page c1 Volume 8, Number 4 Original Music Soundtracks for Movies & Television Action Back In Bond!? pg. 18 MeetTHE Folks GUFFMAN Arrives! WIND Howls! SPINAL’s Tapped! Names Dropped! PLUS The Blue Planet GEORGE FENTON Babes & Brits ED SHEARMUR Celebrity Studded Interviews! The Way It Was Harry Shearer, Michael McKean, MARVIN HAMLISCH Annette O’Toole, Christopher Guest, Eugene Levy, Parker Posey, David L. Lander, Bob Balaban, Rob Reiner, JaneJane Lynch,Lynch, JohnJohn MichaelMichael Higgins,Higgins, 04> Catherine O’Hara, Martin Short, Steve Martin, Tom Hanks, Barbra Streisand, Diane Keaton, Anthony Newley, Woody Allen, Robert Redford, Jamie Lee Curtis, 7225274 93704 Tony Curtis, Janet Leigh, Wolfman Jack, $4.95 U.S. • $5.95 Canada JoeJoe DiMaggio,DiMaggio, OliverOliver North,North, Fawn Hall, Nick Nolte, Nastassja Kinski all mentioned inside! v8n4 covers.qxd 5/13/03 1:58 PM Page c2 On August 19th, all of Hollywood will be reading music. spotting editing composing orchestration contracting dubbing sync licensing music marketing publishing re-scoring prepping clearance music supervising musicians recording studios Summer Film & TV Music Special Issue. August 19, 2003 Music adds emotional resonance to moving pictures. And music creation is a vital part of Hollywood’s economy. Our Summer Film & TV Music Issue is the definitive guide to the music of movies and TV. It’s part 3 of our 4 part series, featuring “Who Scores Primetime,” “Calling Emmy,” upcoming fall films by distributor, director, music credits and much more. It’s the place to advertise your talent, product or service to the people who create the moving pictures. -

We Have Liftoff! the Rocket City in Space SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 29, 2020 • 7:30 P.M

POPS FOUR We Have Liftoff! The Rocket City in Space SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 29, 2020 • 7:30 p.m. • MARK C. SMITH CONCERT HALL, VON BRAUN CENTER Huntsville Symphony Orchestra • C. DAVID RAGSDALE, Guest Conductor • GREGORY VAJDA, Music Director One of the nation’s major aerospace hubs, Huntsville—the “Rocket City”—has been heavily invested in the industry since Operation Paperclip brought more than 1,600 German scientists to the United States between 1945 and 1959. The Army Ballistic Missile Agency arrived at Redstone Arsenal in 1956, and Eisenhower opened NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in 1960 with Dr. Wernher von Braun as Director. The Redstone and Saturn rockets, the “Moon Buggy” (Lunar Roving Vehicle), Skylab, the Space Shuttle Program, and the Hubble Space Telescope are just a few of the many projects led or assisted by Huntsville. Tonight’s concert celebrates our community’s vital contributions to rocketry and space exploration, at the most opportune of celestial conjunctions: July 2019 marked the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon-landing mission, and 2020 brings the 50th anniversary of the U.S. Space and Rocket Center, America’s leading aerospace museum and Alabama’s largest tourist attraction. S3, Inc. Pops Series Concert Sponsors: HOMECHOICE WINDOWS AND DOORS REGIONS BANK Guest Conductor Sponsor: LORETTA SPENCER 56 • HSO SEASON 65 • SPRING musical selections from 2001: A Space Odyssey Richard Strauss Fanfare from Thus Spake Zarathustra, op. 30 Johann Strauss, Jr. On the Beautiful Blue Danube, op. 314 Gustav Holst from The Planets, op. 32 Mars, the Bringer of War Venus, the Bringer of Peace Mercury, the Winged Messenger Jupiter, the Bringer of Jollity INTERMISSION Mason Bates Mothership (2010, commissioned by the YouTube Symphony) John Williams Excerpts from Close Encounters of the Third Kind Alexander Courage Star Trek Through the Years Dennis McCarthy Jay Chattaway Jerry Goldsmith arr. -

Slægten« Gammelt Og Nyt Fra Musicals

Bedste dokumentarfilm: »Gravity is my Enemy« (kort) og »Who Are the De- Gammelt og nyt Bolts? And Where Did They Get Nine- teen Kids?«. fra musicals Bedste visuelle effekter: John Stears, For den musical-interesserede er der John Dykstra, Richard Edlund, Grant spændende gammelt nyt i tre plader redi McCune og Robert Blalack (»Star geret af Hugh Fordin. De tre LP’er rummer Wars«). udelukkende materiale, der ikke kom med i de endelige filmversioner. I nogle tilfælde fordi kvaliteten har været for ringe, i andre Anders Refn tilfælde fordi et musicalnummer, der i sig selv kan være fortrinligt, ikke altid hænger snart klar med ordentligt sammen med resten af filmen. Et eksempel på det sidste turde nok være film efter Wieds Judy Garland-nummeret »Mr. Monotony«, som Irving Berlin skrev til »Easter Parade«. »Slægten« De tre plader rummer i øvrigt så mange sange med Judy Garland (alene eller i sel Bodil 1978 Scene 64 Helmuths stue. Helmuth øver skab med andre musical-stjerner), at pla sig i franske manerer. Optagelse 102. derne alene af den grund er værd at an Bedste danske film: »Mig og Charly« Anders Refn i afslappet stil under ind skaffe sig. Men der er også sange med {Morten Arnfred & Henning Kristiansen). spilningen af et af nyere dansk films mest Fred Astaire (en duet med Nanette Fabray Bedste skuespiller: Frits Helmuth (»Lille ambitiøse projekter, Gustav Wieds »Slæg fra »The Band Wagon«), Betty Garrett, Bet spejl«). ten«, som han selv og Flemming Quist Møl ty Grable, Ethel Merman, Alice Faye, Frank Bedste birolle: Poul Bundgaard (»Hær ler har skrevet manuskript til, og som Sinatra og Gene Kelly. -

If the Stones Were the Bohemian Bad Boys of the British R&B Scene, The

anEHEl s If the Stones were the bohemian bad boys of the British R&B scene, the Animals were its working-class heroes. rom the somber opening chords of the than many of his English R&B contemporaries. The Animals’ first big hit “House of the Rising Animals’ best records had such great resonance because Sun,” the world could tell that this band Burdon drew not only on his enthusiasm, respect and was up to something different than their empathy for the blues and the people who created it, but British Invasion peers. When the record also on his own English working class sensibilities. hitP #1 in England and America in the summer and fall of If the Stones were the decadent, bohemian bad boys 1964, the Beatles and their Mersey-beat fellow travellers of the British R&B scene, the Animals were its working- dominated the charts with songs like “I Want to Hold Your class heroes. “We Gotta Get Out of This Place” and “It’s My Hand” and “Glad All Over.” “House of the Rising Sun,” a tra Life,” two Brill Building-penned hits for the band, were ditional folk song then recently recorded by Bob Dylan on informed as much by working-class anger as by Burdons his debut album, was a tale of the hard life of prostitution, blues influences, and the bands anthemic background poverty and despair in New Orleans. In the Animals’ vocals underscored the point. recording it became a full-scale rock & roll drama, During the two-year period that the original scored by keyboardist Alan Price’s rumbling organ play Animals recorded together, their electrified reworkings of ing and narrated by Eric Burdons vocals, which, as on folk songs undoubtedly influenced the rise of folk-rock, many of the Animals’ best records, built from a foreboding and Burdons gritty vocals inspired a crop of British and bluesy lament to a frenetic howl of pain and protest. -

Gordon Mccallum (Sound Engineer) 26/5/1919 - 10/9/1989 by Admin — Last Modified Jul 27, 2008 02:38 PM

Gordon McCallum (sound engineer) 26/5/1919 - 10/9/1989 by admin — last modified Jul 27, 2008 02:38 PM BIOGRAPHY: Gordon McCallum entered the British film industry in 1935 as a loading boy for Herbert Wilcox at British and Dominions. He soon moved into the sound department and worked as a boom swinger on many films of the late 1930s at Denham, Pinewood and Elstree. During the Second World War he worked with both Michael Powell and David Lean on some of their most celebrated films. Between 1945 and 1984 as a resident sound mixer at Pinewood Studios, he made a contribution to over 300 films, including the majority of the output of the Rank Organisation, as well as later major international productions such as The Day of the Jackal (1973), Superman (1978), Blade Runner (1982) and the James Bond series. In 1972 he won an Oscar for his work on Fiddler on the Roof (1971). SUMMARY: In this interview McCallum discusses many of the personalities and productions he has encountered during his long career, as well as reflecting on developments in sound technology, and the qualities needed to make a good dubbing mixer. BECTU History Project - Interview No. 58 [Copyright BECTU] Transcription Date: 2002-09-20 Interview Date: 1988-10-11 Interviewer: Alan Lawson Interviewee: Gordon McCallum Tape 1, Side 1 Alan Lawson : Now, Mac...when were you born? Gordon McCallum : May 26th 1919. Alan Lawson : And where was that? Gordon McCallum : In Chicago. Alan Lawson : In Chicago? Gordon McCallum : [Chuckles.] Yes...that has been a surprise to many people! Alan Lawson : Yes! Gordon McCallum : I came back to England with my parents, who are English, when I was about four, and my schooling, therefore, was in England - that's why they came back, largely. -

Human' Jaspects of Aaonsí F*Oshv ÍK\ Tke Pilrns Ana /Movéis ÍK\ É^ of the 1980S and 1990S

DOCTORAL Sara MarHn .Alegre -Human than "Human' jAspects of AAonsí F*osHv ÍK\ tke Pilrns ana /Movéis ÍK\ é^ of the 1980s and 1990s Dirigida per: Dr. Departement de Pilologia jA^glesa i de oermanisfica/ T-acwIfat de Uetres/ AUTÓNOMA D^ BARCELONA/ Bellaterra, 1990. - Aldiss, Brian. BilBon Year Spree. London: Corgi, 1973. - Aldridge, Alexandra. 77» Scientific World View in Dystopia. Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Research Press, 1978 (1984). - Alexander, Garth. "Hollywood Dream Turns to Nightmare for Sony", in 77» Sunday Times, 20 November 1994, section 2 Business: 7. - Amis, Martin. 77» Moronic Inferno (1986). HarmorKlsworth: Penguin, 1987. - Andrews, Nigel. "Nightmares and Nasties" in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the MecBa. London and Sydney: Ruto Press, 1984:39 - 47. - Ashley, Bob. 77» Study of Popidar Fiction: A Source Book. London: Pinter Publishers, 1989. - Attebery, Brian. Strategies of Fantasy. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1992. - Bahar, Saba. "Monstrosity, Historicity and Frankenstein" in 77» European English Messenger, vol. IV, no. 2, Autumn 1995:12 -15. - Baldick, Chris. In Frankenstein's Shadow: Myth, Monstrosity, and Nineteenth-Century Writing. Oxford: Oxford Clarendon Press, 1987. - Baring, Anne and Cashford, Jutes. 77» Myth of the Goddess: Evolution of an Image (1991). Harmondsworth: Penguin - Arkana, 1993. - Barker, Martin. 'Introduction" to Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the Media. London and Sydney: Ruto Press, 1984(a): 1-6. "Nasties': Problems of Identification" in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the MecBa. London and Sydney. Ruto Press, 1984(b): 104 - 118. »Nasty Politics or Video Nasties?' in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the Medß.