Libraries and Librarianship in Estonia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reflections on the Work of Janne Tienari Reflections on the Work of Janne Tienari the Work of Janne Writing and Dialogue: Reflectionsacademic On

Academic writing and dialogue: Reflections on the work of Janne Tienari Academic and dialogue: writing Reflections on Reflections of Janne work the Tienari Susan Meriläinen & Eero Vaara ACADEMIC WRITING AND DIALOGUE: REFLECTIONS ON THE WORK OF JANNE TIENARI Editors: Susan Meriläinen & Eero Vaara ISBN 978-952-60-6655-4 (printed) ISBN ISBN 978-952-60-6656-1 (pdf) Unigrafia Helsinki 2016 CONTENTS Contents ...................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ............................................................................................... 5 Virtues and Vices of Janne Tienari .......................................... 7 1.1 Cultivating goodness, Pasi Ahonen ......................................... 7 1.2 The brave king of researchland, Pikka-Maaria Laine ............ 11 1.3 Being masculine, being finnish: Janne the man, Janne suomalainen mies, Scott Taylor & Emma Bell ...................... 14 1.4 Akateeminen urho, Anu Valtonen .......................................... 18 1.5 The progressive personality: The strange case of Janne Tienari, Antti Ainamo ............................................................ 20 A Man Doing Gender Research ............................................... 24 2.1 One flew over the feminist nest, Yvonne Benschop ............... 24 2.2 Q & A on Janne and other male scholars, Charlotta Holgersson ............................................................................. 28 2.3 Dear ‘birthday boy’, Susan Meriläinen ................................. -

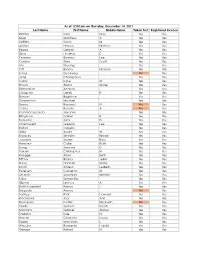

Last Name First Name Middle Name Taken Test Registered License

As of 12:00 am on Thursday, December 14, 2017 Last Name First Name Middle Name Taken Test Registered License Richter Sara May Yes Yes Silver Matthew A Yes Yes Griffiths Stacy M Yes Yes Archer Haylee Nichole Yes Yes Begay Delores A Yes Yes Gray Heather E Yes Yes Pearson Brianna Lee Yes Yes Conlon Tyler Scott Yes Yes Ma Shuang Yes Yes Ott Briana Nichole Yes Yes Liang Guopeng No Yes Jung Chang Gyo Yes Yes Carns Katie M Yes Yes Brooks Alana Marie Yes Yes Richardson Andrew Yes Yes Livingston Derek B Yes Yes Benson Brightstar Yes Yes Gowanlock Michael Yes Yes Denny Racheal N No Yes Crane Beverly A No Yes Paramo Saucedo Jovanny Yes Yes Bringham Darren R Yes Yes Torresdal Jack D Yes Yes Chenoweth Gregory Lee Yes Yes Bolton Isabella Yes Yes Miller Austin W Yes Yes Enriquez Jennifer Benise Yes Yes Jeplawy Joann Rose Yes Yes Harward Callie Ruth Yes Yes Saing Jasmine D Yes Yes Valasin Christopher N Yes Yes Roegge Alissa Beth Yes Yes Tiffany Briana Jekel Yes Yes Davis Hannah Marie Yes Yes Smith Amelia LesBeth Yes Yes Petersen Cameron M Yes Yes Chaplin Jeremiah Whittier Yes Yes Sabo Samantha Yes Yes Gipson Lindsey A Yes Yes Bath-Rosenfeld Robyn J Yes Yes Delgado Alonso No Yes Lackey Rick Howard Yes Yes Brockbank Taci Ann Yes Yes Thompson Kaitlyn Elizabeth No Yes Clarke Joshua Isaiah Yes Yes Montano Gabriel Alonzo Yes Yes England Kyle N Yes Yes Wiman Charlotte Louise Yes Yes Segay Marcinda L Yes Yes Wheeler Benjamin Harold Yes Yes George Robert N Yes Yes Wong Ann Jade Yes Yes Soder Adrienne B Yes Yes Bailey Lydia Noel Yes Yes Linner Tyler Dane Yes Yes -

Culturally Optimised Nutritionally Adequate Food Baskets for Dietary Guidelines for Minimum Wage Estonian Families

nutrients Article Culturally Optimised Nutritionally Adequate Food Baskets for Dietary Guidelines for Minimum Wage Estonian Families Janne Lauk 1,2, Eha Nurk 3, Aileen Robertson 2 and Alexandr Parlesak 2,* 1 Clinical Research Centre, Department of Clinical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, Lund University, Jan Waldenströms gata 35, 214 28 Malmö, Sweden; [email protected] 2 Global Nutrition and Health, University College Copenhagen, Sigurdsgade 26, 2200 Copenhagen, Denmark; [email protected] 3 Department of Nutrition Research, National Institute for Health Development, Hiiu 42, 11619 Tallinn, Estonia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 9 July 2020; Accepted: 24 August 2020; Published: 27 August 2020 Abstract: Although low socioeconomic groups have the highest risk of noncommunicable diseases in Estonia, national dietary guidelines and nutrition recommendations do not consider affordability. This study aims to help develop nutritionally adequate, health-promoting, and culturally acceptable dietary guidelines at an affordable price. Three food baskets (FBs) were optimised using linear programming to meet recommended nutrient intakes (RNIs), or Estonian dietary guidelines, or both. In total, 6255 prices of 422 foods were collected. The Estonian National Dietary Survey (ENDS) provided a proxy for cultural acceptability. Food baskets for a family of four, earning minimum wage, contain between 73 and 96 foods and cost between 10.66 and 10.92 EUR per day. The nutritionally adequate FB that does not follow Estonian dietary guidelines deviates the least (26% on average) from ENDS but contains twice the sugar, sweets, and savoury snacks recommended. The health-promoting FB (40% deviation) contains a limited amount of sugar, sweets, and savoury snacks. -

Name Sex DOB Parent (S) Location VARIATION Aahil M 28-Jan-17

Name Sex DOB Parent (s) Location VARIATION Aahil M 28-Jan-17 Asad Shah London, UK ? Adeline F 1-Nov-94 Adeline Esdale Northern Ireland E198K Adrian Fran M 20-Feb-14 Gardana Klaic Croatia E198k Alexander M 18-Jan-00 Luba Yotkova South Jersey, USA E198K Alex M 1-Nov-00 Leslie Weston Maryland, USA F473L Amelia F 11-May-13 Aga Agnieszka Maliszewska UK E198K Ana F 12-Sep-99 Elena Goloborodko New York, USA E198K Antonio M 22-Aug-13 Fernando Jose Jaimes Plata Columbia E198K Arthur M 12-Dec-11 Tine Larsen & Martin Kirchgässner Denmark E200K Arvid Sakura Holmkvist Sweden ? Asa M Oct 7, 2007 Kim Wilson Mercer, Tennessee, USA E198K Austin M Abby & Tom Anghileri Cambridge, UK Q211P Ava F 20-Nov-13 Pauline G Corral AZ, USA E200K Avianna F 16-Mar-11 Nancy DeOrta Mesa, AZ, USA E197K Billy M Reets and David Lawrence Australia D251V Carlos M 27-Oct-17 Noelia Izpe Spain E198K Cash M 10-Apr-17 Virgil and Holly Snell Texas, USA E200K Cathaoir M Ciara Devlin Mulgrew N Ireland ? Camden M 18-Aug-13 Kristen Sontag-Long Michigan, USA E420K Charlotte F 26-Nov-12 Bethany Blackham Geiger Ohio, USA R253P Connah M 24-Feb-04 Crystal Newman Australia E198K Cooper M 28-Dec-14 Melissa & Dean Hadley Australia R85* Danny M Jennifer Openshaw-Feigenbaum Long Island, NY, USA W207R Delphine F 29-Nov-15 Amanda Mark Minessota, USA E198K Eden F 5-May-99 Sandra Jenssen Kanner & Nathaniel Kanner NY, USA W207R Virginia, USA Ella F 11-Dec-04 Shelby and Greg Holmes Butler E198K Ela F 18mo Nurit and Avi Kaminski Israel ? Elvi F Elina Levaniemi & Janne Koski Helsinki, Finland E198K Emily -

The Nordic Emergency Medical Services 1 8 FUTURE WORK 43

The Nordic Emergency Medical Services PROJECT ON DATA COLLECTION AND BENCHMARKING 2014 - 2018 Report ORDERING NR IS-2750 CONTENT Summary 3 1 BACKGROUND 5 1.1 Nordic EMS project –data collection and benchmarking 5 1.2 Why quality indicators are important 5 1.3 Organizing of the project 6 1.4 Other data collection initiatives 8 2 THE EMS SYSTEMS IN THE NORDIC COUNTRIES 9 2.1 Norway 9 2.2 Sweden 11 2.3 Denmark 13 2.4 Iceland 15 2.5 Finland 17 3 COMMON NORDIC DEFINITIONS 20 3.1 The Emergency Medical Dispatch center 20 3.2 Data availability and data collection 23 3.3 Quality indicator template 24 3.4 Common Nordic EMS time points and time intervals 24 3.5 Data structure and definitions 26 3.6 Preconditions 26 4 WORKING GROUP KEY STATISTICS 27 4.1 Introduction 27 4.2 Selecting Nordic quality indicators 27 4.3 Key statistics and process indicators recommended by the Working group 29 4.4 Preliminary results on key statistics and process quality indicators 29 5 WORKING GROUP ASSESS, TREAT AND RELEASE 35 5.1 Quality indicators for patient group Assess treat and release 35 5.2 Data structure for Assess, treat and release - patients 36 5.3 Research is needed 37 6 WORKING GROUP AMI, CARDIAC ARREST AND STROKE 39 6.1 Introduction 39 6.2 Pre-assumptions 39 7 WORKING GROUP ICPC-2 41 7.1 Introduction 41 7.2 Use of ICPC-2 in EMS 41 The Nordic Emergency Medical Services 1 8 FUTURE WORK 43 8.1 Publishing of the report 43 8.2 Follow up in a Nordic Ministry Council 43 8.3 Challenges for the future 44 9 DEFINITIONS OF TERMS 45 9.1 Definition of basic concepts and terms 45 10 ATTACHMENT 47 10.1 Descriptions of the Nordic quality indicators 47 11 Validation report 56 The Nordic Emergency Medical Services 2 Summary The Nordic countries are among the top-ranking health care services1 and have a long tradition of collecting data, documenting and publishing their outcomes for the patients. -

Baby Boy Names Registered in 2017

Page 1 of 43 Baby Boy Names Registered in 2017 # Baby Boy Names # Baby Boy Names # Baby Boy Names 1 Aaban 3 Abbas 1 Abhigyan 1 Aadam 2 Abd 2 Abhijot 1 Aaden 1 Abdaleh 1 Abhinav 1 Aadhith 3 Abdalla 1 Abhir 2 Aadi 4 Abdallah 1 Abhiraj 2 Aadil 1 Abd-AlMoez 1 Abic 1 Aadish 1 Abd-Alrahman 1 Abin 2 Aaditya 1 Abdelatif 1 Abir 2 Aadvik 1 Abdelaziz 11 Abraham 1 Aafiq 1 Abdelmonem 7 Abram 1 Aaftaab 1 Abdelrhman 1 Abrham 1 Aagam 1 Abdi 1 Abrielle 2 Aahil 1 Abdihafid 1 Absaar 1 Aaman 2 Abdikarim 1 Absalom 1 Aamir 1 Abdikhabir 1 Abu 1 Aanav 1 Abdilahi 1 Abubacarr 24 Aarav 1 Abdinasir 1 Abubakar 1 Aaravjot 1 Abdi-Raheem 2 Abubakr 1 Aarez 7 Abdirahman 2 Abu-Bakr 1 Aaric 1 Abdirisaq 1 Abubeker 1 Aarish 2 Abdirizak 1 Abuoi 1 Aarit 1 Abdisamad 1 Abyan 1 Aariv 1 Abdishakur 13 Ace 1 Aariyan 1 Abdiziz 1 Achier 2 Aariz 2 Abdoul 4 Achilles 2 Aarnav 2 Abdoulaye 1 Achyut 1 Aaro 1 Abdourahman 1 Adab 68 Aaron 10 Abdul 1 Adabjot 1 Aaron-Clive 1 Abdulahad 1 Adalius 2 Aarsh 1 Abdul-Azeem 133 Adam 1 Aarudh 1 Abdulaziz 2 Adama 1 Aarus 1 Abdulbasit 1 Adamas 4 Aarush 1 Abdulla 1 Adarius 1 Aarvsh 19 Abdullah 1 Adden 9 Aaryan 5 Abdullahi 4 Addison 1 Aaryansh 1 Abdulmuhsin 1 Adedayo 1 Aaryav 1 Abdul-Muqsit 1 Adeel 1 Aaryn 1 Abdulrahim 1 Adeen 1 Aashir 2 Abdulrahman 1 Adeendra 1 Aashish 1 Abdul-Rahman 1 Adekayode 2 Aasim 1 Abdulsattar 4 Adel 1 Aaven 2 Abdur 1 Ademidesireoluwa 1 Aavish 1 Abdur-Rahman 1 Ademidun 3 Aayan 1 Abe 5 Aden 1 Aayandeep 1 Abed 1 A'den 1 Aayansh 21 Abel 1 Adeoluwa 1 Abaan 1 Abenzer 1 Adetola 1 Abanoub 1 Abhaypratap 1 Adetunde 1 Abantsia 1 Abheytej 3 -

First Name Americanization Patterns Among Twentieth-Century Jewish Immigrants to the United States

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2017 From Rochel to Rose and Mendel to Max: First Name Americanization Patterns Among Twentieth-Century Jewish Immigrants to the United States Jason H. Greenberg The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1820 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] FROM ROCHEL TO ROSE AND MENDEL TO MAX: FIRST NAME AMERICANIZATION PATTERNS AMONG TWENTIETH-CENTURY JEWISH IMMIGRANTS TO THE UNITED STATES by by Jason Greenberg A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Linguistics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Linguistics, The City University of New York 2017 © 2017 Jason Greenberg All Rights Reserved ii From Rochel to Rose and Mendel to Max: First Name Americanization Patterns Among Twentieth-Century Jewish Immigrants to the United States: A Case Study by Jason Greenberg This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Linguistics in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in Linguistics. _____________________ ____________________________________ Date Cecelia Cutler Chair of Examining Committee _____________________ ____________________________________ Date Gita Martohardjono Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT From Rochel to Rose and Mendel to Max: First Name Americanization Patterns Among Twentieth-Century Jewish Immigrants to the United States: A Case Study by Jason Greenberg Advisor: Cecelia Cutler There has been a dearth of investigation into the distribution of and the alterations among Jewish given names. -

Challenges in the 21St Century Edited by Anu Koivunen, Jari Ojala and Janne Holmén

The Nordic Economic, Social and Political Model The Nordic model is the 20th-century Scandinavian recipe for combining stable democracies, individual freedom, economic growth and comprehensive systems for social security. But what happens when Sweden and Finland – two countries topping global indexes for competitiveness, productivity, growth, quality of life, prosperity and equality – start doubting themselves and their future? Is the Nordic model at a crossroads? Historically, consensus, continuity, social cohesion and broad social trust have been hailed as key components for the success and for the self-images of Sweden and Finland. In the contemporary, however, political debates in both countries are increasingly focused on risks, threats and worry. Social disintegration, political polarization, geopolitical anxieties and threat of terrorism are often dominant themes. This book focuses on what appears to be a paradox: countries with low-income differences, high faith in social institutions and relatively high cultural homogeneity becoming fixated on the fear of polarization, disintegration and diminished social trust. Unpacking the presentist discourse of “worry” and a sense of interregnum at the face of geopolitical tensions, digitalization and globalization, as well as challenges to democracy, the chapters take steps back in time and explore the current conjecture through the eyes of historians and social scientists, addressing key aspects of and challenges to both the contemporary and the future Nordic model. In addition, the functioning and efficacy of the participatory democracy and current protocols of decision-making are debated. This work is essential reading for students and scholars of the welfare state, social reforms and populism, as well as Nordic and Scandinavian studies. -

1 Norwegian in the American Midwest

Norwegian in the American Midwest: A common lexicolect Janne Bondi Johannessen* and Signe Laake** *MultiLing, Department of Linguistics and Scandinavian Studies ** Department of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages University of Oslo Abstract The American Midwest is an area that stretches over huge distances. Yet it seems that the Norwegian language in this whole area has some similarities, particularly at the lexical level. Comparisons of three types of vocabulary across the whole area, as well as across time, building on accounts in the previous literature from Haugen (1953) onwards, are carried out. The results of these comparisons convince the authors that it is justified to refer to this language as one lexically defined dialect, which we call lexicolect. Keywords: Heritage Norwegian, loanwords, types of words, one common language variety, different dialects, koiné, diglossia, lexicolect 1. Introduction1 During the first fieldwork the present authors undertook in 2010, an unfamiliar use of certain words came to our attention. This was all the more noticeable since it happened across vast distances in the American Midwest. That a new speech variety can develop in a close-knit community is not surprising. It is also possible to see how members of a society tied together by mass media, especially radio, television and social media, can develop a common language variety. However, when people live far apart in a vast and sparsely populated area like the American Midwest, one would have thought it less likely that the language would develop common linguistic features. Add to this that travel was hard, expensive and time-consuming, and the relevant mass media only existed in print. -

Orange County Public Schools Teachers Out-Of-Field As of 08/02/2019 1

Orange County Public Schools Teachers Out-of-Field as of 08/02/2019 Description Last Name First Name Job Title Out of Field Area Out of Field Area ACCELERATION EAST ROBSON SHELLEY LANGUAGE ARTS ESOL Endorsement ACCELERATION EAST TRIMBLE CAROLINE PHYSICAL EDUCATION Health ACCELERATION WEST CURRY DAPHNEE LANGUAGE ARTS ESOL Endorsement ALOMA ELEMENTARY MCAULIFFE KATHERINE TEACHER - GRADE FIVE ESOL Endorsement ALOMA ELEMENTARY KAYE MARYBETH TEACHER - GRADE FOUR ESOL Endorsement ALOMA ELEMENTARY RODRIGUEZ ROSANNA TEACHER - GRADE ONE ESOL Endorsement ALOMA ELEMENTARY LANGHORST NICOLE TEACHER - GRADE ONE ESOL Endorsement ALOMA ELEMENTARY HANSEN KELLIE GIFTED Gifted Endorsement ALOMA ELEMENTARY QUINONEZ PRISCILLA GIFTED Gifted Endorsement ALOMA ELEMENTARY LIVINGSTON JOYCE TEACHER - GRADE FOUR Gifted Endorsement ANDOVER ELEMENTARY AYALA OJEDA ERICKA AUTISTIC Autism Endorsement ANDOVER ELEMENTARY ACEVEDO ACEVEDO GLORIBEL AUTISTIC ESOL Endorsement ANDOVER ELEMENTARY RIOS RODRIGUEZ JAMARY KINDERGARTEN TEACHER ESOL Endorsement ANDOVER ELEMENTARY HOWE LEEANNE TEACHER - GRADE ONE ESOL Endorsement ANDOVER ELEMENTARY SELZER MADELIN TEACHER - GRADE ONE ESOL Endorsement ANDOVER ELEMENTARY ATIENZA KRYSTAL TEACHER - GRADE THRE ESOL Endorsement ANDOVER ELEMENTARY RICH CHRISTINA TEACHER - GRADE THRE ESOL Endorsement APOPKA ELEMENTARY WASHINGTON MONICA INSTRUCTIONAL COACH ESOL Endorsement APOPKA ELEMENTARY SMITH ANGEL KINDERGARTEN TEACHER ESOL Endorsement APOPKA ELEMENTARY MCELROY MARLEY TEACHER - GRADE FOUR ESOL Endorsement APOPKA ELEMENTARY PENA MEJIA ROSALBA -

Declarations of Rockford Swedes 1859-1870 Nils William Olsson

Swedish American Genealogist Volume 1 | Number 1 Article 12 3-1-1981 Declarations of Rockford Swedes 1859-1870 Nils William Olsson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/swensonsag Part of the Genealogy Commons, and the Scandinavian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Olsson, Nils William (1981) "Declarations of Rockford Swedes 1859-1870," Swedish American Genealogist: Vol. 1 : No. 1 , Article 12. Available at: https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/swensonsag/vol1/iss1/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Augustana Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Swedish American Genealogist by an authorized editor of Augustana Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Declarations of Intention by Swedes in Rockford 1859-1870 Nils William Olsson Declarations of intention to become United States citizens and the final naturalization documents are among the best sources for determinging the pres ence in a given community of early Swedish settlers. Up until the time that the law was changed in 1906, with the establishment of the Immigration and Natur alization Service under the U.S. Department of Justice, which then took over the sole function of the naturalization of foreign subjects, any foreigner in the United States had been able to secure his or her naturalization in almost any court of justice, ranging from the U.S. District courts to the police courts of individual cities and towns. Any foreigner coming to the United States could become a citizen of this country, after having resided here a minimum of five years, renouncing his loyalty to the sovereign of the country of his birth, and after having taken out the "first paper" or the declaration of intention, which could be done a year after arrival. -

Overlap in Present-Day Finnish Place Names, Given Names, and Surnames

Unni Leino Overlap in present-day Finnish place names, given names, and surnames 1. Names and patterns One of the fundamental questions – if not the question – in onomastics is the nature and origins of proprical expressions. Until the mid-20th century, the prevailing consensus was that names were descriptive in origin. While this was especially relevant in the case of toponyms, the origins of anthroponyms was viewed similarly. As a general onomastic principle this traces back to GoTTfrIEd WILHELm VoN LEIBNIz (1710): “Illud enim pro axiomate habeo, omnia nomina quæ vocamus propria, aliquando appellativa fuisse, alioqui ratione nulla constarent.” Especially in the past few decades, scholars have increasingly started to disagree with this view, to the extent of suggesting that proper names are in fact primary and appellative nouns a secondary development (e.g. VAN LANGENdoNck 2007: 116–118), or that properhood itself is not a categorical property but rather a matter of pragmatics (e.g. COATES 2005, 2006). In any case, however, it is clear that there are interactions between appellative nouns and proper names, and between proper names in different categories. The transition from seeing names as a development of descriptive appellations started in the latter half of the 20th century, when several onomasticians (notably VINcENT BLANÁr and rudoLf ŠrÁmEk in Czechoslovakia, and KURT zILLIAcus and EEro kIVINIEmI in Finland) began formulating a theoretical framework that saw naming as a pattern-based process. Most of this pioneer work was done in the context of toponyms (e.g. zILLIAcus 1966, ŠrÁmEk 1972, kIVINIEmI 1977), but the model-based approach applies equally well to anthroponyms (BLANÁr 1990, PAIKKALA 2004: 44–51) and is compatible with a cognitive view on linguistics (sJöBLom 2006, LEINO 2007).