Ang Magkaribal: a History of Road Versus Rail in Metropolitan Manila, 1957-1985

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BINONDO FOOD TRIP (4 Hours)

BINONDO FOOD TRIP (4 hours) Eat your way around Binondo, the Philippines’ Chinatown. Located across the Pasig River from the walled city of Intramuros, Binondo was formally established in 1594, and is believed to be the oldest Chinatown in the world. It is the center of commerce and trade for all types of businesses run by Filipino-Chinese merchants, and given the historic reach of Chinese trading in the Pacific, it has been a hub of Chinese commerce in the Philippines since before the first Spanish colonizers arrived in the Philippines in 1521. Before World War II, Binondo was the center of the banking and financial community in the Philippines, housing insurance companies, commercial banks and other financial institutions from Britain and the United States. These banks were located mostly along Escólta, which used to be called the "Wall Street of the Philippines". Binondo remains a center of commerce and trade for all types of businesses run by Filipino- Chinese merchants and is famous for its diverse offerings of Chinese cuisine. Enjoy walking around the streets of Binondo, taking in Tsinoy (Chinese-Filipino) history through various Chinese specialties from its small and cozy restaurants. Have a taste of fried Chinese Lumpia, Kuchay Empanada and Misua Guisado at Quick Snack located along Carvajal Street; Kiampong Rice and Peanut Balls at Café Mezzanine; Kuchay Dumplings at Dong Bei Dumplings and the growing famous Beef Kan Pan of Lan Zhou La Mien. References: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Binondo,_Manila TIME ITINERARY 0800H Pick-up -

Comprehensive Land Use Plan 2016 - 2025

COMPREHENSIVE LAND USE PLAN 2016 - 2025 PART 3: SECTORAL PROFILE 3.1. INFRASTRUCTURE, FACILITIES AND UTILITIES 3.1.1. Flood Control Facilities 3.1.1.1. “Bombastik” Pumping Stations Being a narrow strip of land with a relatively flat terrain and with an aggregate shoreline of 12.5 kilometers that is affected by tidal fluctuations, flooding is a common problem in Navotas City. This is aggravated by pollution and siltation of the waterways, encroachment of waterways and drainage right-of-ways by legitimate and informal settlers, as well as improper waste disposal. The perennial city flooding inevitably became a part of everyday living. During a high tide with 1.2 meter elevation, some parts of Navotas experience flooding, especially the low-lying areas along the coast and riverways. As a mitigating measure, the city government - thru the Local Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Office - disseminates information about the heights of tides for a specific month. This results in an increased awareness among the residents on the time and date of occurrence of high tide. During rainy days, flooding reach higher levels. The residents have already adapted to this situation. Those who are well-off are able to install their own preventive measures, such as upgrading their floorings to a higher elevation. During the term of the then Mayor and now Congressman, Tobias M. Tiangco, he conceptualized a project that aims to end the perennial flooding in Navotas. Since Navotas is surrounded by water, he believed that enclosing the city to prevent the entry of water during high tide would solve the floods. -

Lrt Line 2 East Extension Project

Roadmap for Transport Infrastructure Development for Metro Manila and Its Surrounding Areas (Region III and Region IV-A) Main Points of the Roadmap Technical Assistance from the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Roadmap Study Objective Study Period To formulate “Transportation March 2013 – March 2014 Infrastructure Roadmap” for sustainable development of Metro Manila and its surrounding areas Stakeholders Consulted (Region III and IV-A) NEDA DPWH Outputs DOTC MMDA Dream plan towards 2030 Others (donors, private sectors, etc.) Roadmap towards 2016 and 2020 Priority projects 2 Significance of the study area: How to ensure sustainable growth of Metro Manila and surrounding regions. Study Area Nueva Ecija Aurora Tarlac GCR: MManila, Region III, Region IV-A Region III 100km Mega Manila: MManila, Bulacan, Rizal, Laguna, Cavite Metro Manila : 17 cities/municipality Pampanga Metro Manila shares 36% of GDP GCR shares 62% of GDP (Population :37%) Bulacan 50km Popuation Population growth rate (%/year) GRDP Metro (000) (Php billion) Rizal (1) GRDP by sector; growth rate (%/year), Manila 25,000 (2) 4,000 (3) sector share (%) 6.3% 2.0% 20,000 1 18 1.5% 3,000 15,000 Cavite 1.8% 3.1% Laguna 2,000 2.4% 6.1% 10,000 6 2.6% 81 2.1% 32 4.6% 63 17 1,000 Batangas 5,000 17 31 28 41 42 31 51 41 Region IV-A 0 0 MetroMetro Region IIIIII RegionRegion IV-A IV Visayas Mindanao ManilaManila Growth rate of population & GRDP is between 2000 and 2010 3 Rapid growth of Metro Manila, 1980 - 2010 1980 2010 2010/’80 Population (000) 5,923 11,856 2.0 Roads (km) 675 1,032 1.5 GRDP @ 2010 price (Php billion) 1,233 3,226 2.6 GRDP per Capita (Php 000) 208 272 1.3 No. -

Ccn Tin Importer Im0006021794 430968150000 Daesang Ricor Corporation Im0002959372 003873536000 Westpoint Industrial Sales Co

CCN TIN IMPORTER IM0006021794 430968150000 DAESANG RICOR CORPORATION IM0002959372 003873536000 WESTPOINT INDUSTRIAL SALES CO. INC. IM0002992817 000695510000 ASIAN CARMAKERS CORPORATION IM0002963779 232347770000 STRONG LINK DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION IM0003299511 002624091000 TABAQUERIA DE FILIPINAS INC. IM0003063011 217711150000 ASIAWIDE REFRESHMENTS CORPORATION IM0002963639 001007787000 GX INTERNATIONAL INC. IM0006830714 456650820000 MOBIATRIX INC IM0003014592 002765139000 INNOVISTA TECHNOLOGIES INC. IM0003214699 005393872000 MONTEORO CHEMICAL CORPORATION IM0004340299 000126640000 LINKWORTH INTERNATIONAL INC. IM0006804179 417272052000 EATON INDUSTRIES PHILIPPINES LLC PH IM0002957590 000419293000 ALLEGRO MICROSYSTEMS PHILS. INC. IM0004143132 001030408000 PUENTESPINA ORCHIDS AND TROPICAL IM0003131297 004558769000 ARCHITECKS METAL SYSTEMS INC. IM0003025799 103873913000 MCMASTER INTERNATIONAL SALES IM0002973979 000296020000 CARE PRODUCTS INC IM0003014231 001026198000 INFRATEX PHILIPPINES INC. IM0002962691 000288655000 EURO-MED LABORATORIES PHILS. INC. IM0003031438 006818264000 NORTHFIELDS ENTERPRISES INT'L. INC. IM0003170217 002925850000 KENRICH INT'L . DISTRIBUTOR INC. IM0003259994 000365522000 KAMPILAN MANUFACTURING CORPORATION IM0003132498 103901522000 PEONY MERCHANDISING IM0002959496 204366533000 GLOBEWIDE TRADING IM0002966514 000070213000 NORKIS TRADING CO INC. IM0003232492 000117630000 ENERGIZER PHILIPPINES INC. IM0003131513 000319974000 HI-Q COMMERCIAL.INC IM0003035816 000237662000 PHILIPPINE INTERNATIONAL DEV'T INC. IM0003090795 113041122000 -

Railway Transport Planning and Implementation in Metropolitan Manila, 1879 to 2014

Journal of the Eastern Asia Society for Transportation Studies, Vol.12, 2017 Railway Transport Planning and Implementation in Metropolitan Manila, 1879 to 2014 Jose Regin F. REGIDOR a, Dominic S. ALOC b a,b Institute of Civil Engineering, College of Engineering, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City, 1101, Philippines a E-mail: [email protected] b E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: This paper presents a history of rail-based transportation in Metropolitan Manila. This history focuses on urban transport including rail-based streetcars or trams that started operations in the 1880’s but were destroyed during the Second World War and never to be revived. Several plans are discussed. Among these plans are proposals for a monorail network, a heavy rail system, and the more current rail transit plans from recent studies like MMUTIS. An assessment of public transportation in Metro Manila is presented with emphasis on the counterfactual scenario of what could have been a very different metropolis if people could commute using an extensive rail transit system compared to what has been realized so far for the metropolis. Recommendations for the way forward for rail transportation in Metro Manila and further studies are stated in conclusion. Keywords: Transport Planning, Rail Transit, History 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background Rail-based urban transport has had a relatively long history in Metro Manila despite what now seems to be a backlog of rail transportation in the capital city of the Philippines. In fact, the dominant mode of public transportation used to be rail-based with Manila and its adjoining areas served by a network of electric tranvias (i.e., streetcars) and heavy rail lines. -

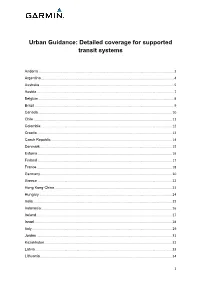

Urban Guidance: Detailed Coverage for Supported Transit Systems

Urban Guidance: Detailed coverage for supported transit systems Andorra .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Argentina ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Australia ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Austria .................................................................................................................................................... 7 Belgium .................................................................................................................................................. 8 Brazil ...................................................................................................................................................... 9 Canada ................................................................................................................................................ 10 Chile ..................................................................................................................................................... 11 Colombia .............................................................................................................................................. 12 Croatia ................................................................................................................................................. -

Intramuros During the American Colonization

Intramuros during the American Colonization Irene G. BORRAS1 University of Santo Tomas MANILA ABSTRACT Intramuros, located in the capital city of the Philppines, became a symbolic siting that represents one’s social status and importance in society during the Spanish colonization. Also known as the “Walled City,” Intramuros is home to the oldest churches, schools, and government offices in the Philippines. When the Americans decided to colonized the Philippines, they did not have to conquer all the islands of the archipelago. They just have to secure Intramuros and the entire country fell to another colonizer. The goal of this paper is to identify the effects of creating a “center” or a city––from the way it is planned and structured––on one’s way of thinking and later on the attitude of the people towards the city. Specifically, the paper will focus on the important and symbolic structures near and inside the “walled city” and its effects on the mindset of the people towards the institutions that they represent. The paper will focus on the transition of Intramuros from a prestigious and prominent place during the Spanish colonization to an ordinary and decaying “Walled City” during the American period. Significantly, the paper will discuss the development of “Extramuros” or those settlements outside the walled city. It will give focus on the planning of Manila by Daniel Burnham during the American period which was basically focused on the development of the suburbs outside Intramuros. The paper will also discuss the important establishments built outside the Walled City during the American period. -

Institutional Spillover Effects of Infrastructure Investment Funded by Foreign Aid: Evidence from a Road Construction Project in Manila

Journal of the Eastern Asia Society for Transportation Studies, Vol. 8, 2010 Institutional Spillover Effects of Infrastructure Investment Funded by Foreign Aid: Evidence from a Road Construction Project in Manila Hironori Kato Crispin Emmanuel D. Diaz Associate Professor Associate Professor Department of Civil Engineering School of Urban and Regional Planning Graduate School of Engineering University of the Philippines University of Tokyo Diliman, Quezon City 7-3-1, Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 1101, Philippines 113-8656 Japan Telefax: +63-2-9206854 Fax: +81-3-5841-7451 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Marie ONGA Master’s Student Department of Civil Engineering Graduate School of Engineering University of Tokyo 7-3-1, Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-8656 Japan Fax: +81-3-5841-8506 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: This paper empirically identifies institutional spillover effects, i.e. the influence of one institution's actions, indirectly or unintentionally, on the actions of another institution, that resulted during the implementation of the Circumferential Road No. 3 construction project in Manila, Philippines which was funded by foreign aid. The paper shows an analysis of the mechanism of the effects, based on an examination of the behavioral process of the main actors - the donor, the recipient, the consulting company, and local organizations. First, the paper looked at the project purposes, processes, and outcomes based on relevant literature and interviews with local stakeholders. Then, focusing on a key event, institutional spillovers effects were identified. These spillover effects were examined through a process that identified the major actors, their motivations, available actions and strategies. -

Intellectual Property Center, 28 Upper Mckinley Rd. Mckinley Hill Town Center, Fort Bonifacio, Taguig City 1634, Philippines Tel

Intellectual Property Center, 28 Upper McKinley Rd. McKinley Hill Town Center, Fort Bonifacio, Taguig City 1634, Philippines Tel. No. 238-6300 Website: http://www.ipophil.gov.ph e-mail: [email protected] Publication Date: 13 April 2021 1 ALLOWED MARKS PUBLISHED FOR OPPOSITION .................................................................................................... 2 1.1 ALLOWED NATIONAL MARKS ............................................................................................................................................. 2 Intellectual Property Center, 28 Upper McKinley Rd. McKinley Hill Town Center, Fort Bonifacio, Taguig City 1634, Philippines Tel. No. 238-6300 Website: http://www.ipophil.gov.ph e-mail: [email protected] Publication Date: 13 April 2021 1 ALLOWED MARKS PUBLISHED FOR OPPOSITION 1.1 Allowed national marks Application Filing No. Mark Applicant Nice class(es) Number Date 23 January 1 4/2009/00000782 ACZÉE EON PHARMATEK, INC. [PH] 3 2009 7 VS Makan Food Corporation 2 4/2017/00019774 December KUDETAH 43 [PH] 2017 8 August 3 4/2019/00014005 TING`S KITCHEN Ting Ting Xu [PH] 30 and32 2019 3 Sunwealth Land Development 4 4/2019/00015574 September CTC ARCADE 36 Corporation [PH] 2019 12 FERCAMPO Louis Maclean Far East Inc. 5 4/2019/00019668 November 1 FERTILIZER [PH] 2019 4 TITA TRAINING IS Personal Collection Direct 6 4/2019/00020973 December 35 THE ANSWER Selling, Inc. [PH] 2019 4 RITA RECRUITMENT Personal Collection Direct 7 4/2019/00020974 December 35 IS THE ANSWER Selling, Inc. [PH] 2019 4 CITA COLLECTION IS Personal Collection Direct 8 4/2019/00020975 December 35 THE ANSWER Selling, Inc. [PH] 2019 20 Huangteng Group Co., Ltd. 9 4/2019/00022020 December 37 [CN] 2019 1 March 10 4/2019/00501118 SIZZLING CITY Abo, Ranulfo A. -

JEEP Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

JEEP bus time schedule & line map Ever Gotesco Grand Central, Rizal Avenue, JEEP Caloocan City →25th St / Antonio C. Delgado View In Website Mode Intersection, Manila The JEEP bus line Ever Gotesco Grand Central, Rizal Avenue, Caloocan City →25th St / Antonio C. Delgado Intersection, Manila has one route. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Ever Gotesco Grand Central, Rizal Avenue, Caloocan City →25th St / Antonio C. Delgado Intersection, Manila: 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest JEEP bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next JEEP bus arriving. Direction: Ever Gotesco Grand Central, Rizal JEEP bus Time Schedule Avenue, Caloocan City →25th St / Antonio C. Ever Gotesco Grand Central, Rizal Avenue, Caloocan Delgado Intersection, Manila City →25th St / Antonio C. Delgado Intersection, 42 stops Manila Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:00 AM - 10:00 PM Monday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Ever Gotesco Grand Central, Rizal Avenue, Caloocan City Tuesday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Macdonalds, Rizal Avenue, Caloocan City Wednesday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Thursday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Rizal Avenue / Asistio Intersection, Caloocan City Friday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Rizal Ave / 8th Ave West, Caloocan City, Manila Saturday 12:00 AM - 10:00 PM 8th Avenue, Philippines Rizal Ave / 7th Ave West, Caloocan City, Manila Jcsgo Caloocan, Rizal Ave / 6th Ave West, Caloocan City, Manila JEEP bus Info C. Susano, Philippines Direction: Ever Gotesco Grand Central, Rizal Avenue, Caloocan City →25th St / Antonio C. Delgado Circumferential Road 3 / M.H. -

The Matriyoshka Settlement: a Historical Geography of the Evolving Definitions of Metropolitan Manila During the Marcos Era

The Matriyoshka Settlement: A Historical Geography of the Evolving Definitions of Metropolitan Manila during the Marcos Era Marco Stefan B. Lagman Department of Geography University of the Philippines-Diliman Abstract For the past four decades, it has become natural for Filipinos to perceive Metropolitan Manila as an agglomeration of 17 settlements all of which, save for one, has attained the status of highly urbanized city. While this particular geographic definition of Metro Manila has become normalized into popular consciousness, many have a very faint idea of its history as a planning and administrative creation. Using studies from the education, marketing and economics disciplines, urban and transport planning documents, journal articles, and studies during the 1960s to the early part of the 1980s, and geographic information systems knowledge, this paper seeks to provide a history of how Manila and its surrounding towns eventually came to be perceived as a metropolitan region that became the object of research, policy-making, planning, and administration by the state and other institutions. This study also aims to emphasize that the Metro Manila that we know today underwent several iterations as planners and policymakers seemingly employed several criteria such as urbanization, land use, population, and even car registration and traffic congestion as the bases for which to include in the metropolitan region. By rendering these into Geographic Information Systems-based maps, the multiple versions of the Metropolitan Manila Area over the years could be best understood, appreciated, and imagined in visual format. Moreover, as Metro Manila was being defined, an even larger area called the Manila Bay Metropolitan Region that included the former was being proposed by the authorities as a means for further directing growth and development of the largest cluster of rapidly urbanizing settlements in the country during the 1970s. -

52083-002: Malolos-Clark Railway Project

Environmental Monitoring Report Semi-annual Environmental Monitoring Report No. 1 March 2020 PHI: Malolos-Clark Railway Project – Tranche 1 Volume VI September 2019 – March 2020 Prepared by the Project Management Office (PMO) of the Department of Transportation (DOTr) for the Government of the Republic of the Philippines and the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 30 March 2020) Currency unit – Philippine Peso (PHP) PHP1.00 = $0.02 $1.00 = PHP50.96 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank BMB – Biodiversity Management Bureau Brgy – Barangay CCA – Climate Change Adaptation CCC – Climate Change Commission CDC – Clark Development Corporation CEMP – Contractor’s Environmental Management Plan CENRO – City/Community Environment and Natural Resources Office CIA – Clark International Airport CIAC – Clark International Airport Corporation CLLEx – Central Luzon Link Expressway CLUP – Comprehensive Land Use Plan CMR – Compliance Monitoring Report CMVR – Compliance Monitoring and Validation Report CNO – Certificate of No Objection CPDO – City Planning and Development Office DAO – DENR Administrative Order DD / DED – Detailed Design Stage / Detailed Engineering Design Stage DENR – Department of Environment and Natural Resources DepEd – Department of Education DIA – Direct Impact Area DILG – Department of Interior and Local Government DOH – Department of Health DOST – Department of Science and Technology DOTr – Department of Transportation DPWH – Department of Public Works and Highways DSWD – Department of Social Welfare and Development