Derozio and the Bengal Renaissance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hinduism” and the Problem of Self- Actualisation in the Colonial Era: Critical Reflections

SOUTH ASIA INSTITUTE PAPERS BEITRÄGE DES SÜDASIEN-INSTITUTS HEIDELBERG Amiya P. Sen (Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi) “Hinduism” and the Problem of Self- Actualisation in the Colonial Era: Critical Reflections CONTACT South Asia Institute Heidelberg University Im Neuenheimer Feld 330 D-69120 Heidelberg ISSUE 01 2015 P: +49(0)6221-548900 21. 8. 2015 F: +49(0)6221-544998 [email protected] ISSN 2365-399X www.sai.uni-heidelberg.de “Hinduism” and the Problem of Self-Actualisation in the Colonial Era: Critical Reflections Amiya P. Sen This paper is the text of a lecture delivered at the South Asia Institute, Hei- delberg, on May 20, 2015, with footnotes added. It discusses how schol- arly perceptions of colonial Hinduism have visibly shifted trajectory over the years. Relating how Hinduism has moved from being ‘discovered’ in the eighteenth century to be seen as discursively ‘invented’ or ‘imagined’ in the nineteenth, it argues that in colonial India, internally generated debates about the origin and nature of Hinduism paralleled ascriptions originating outside but failed to attract adequate attention. It also seeks to ask if not also to definitively answer certain key theoretical questions. For instance, even allowing for the fact that social and religious identities are always po- rous, does it still make sense to ask if unstable and fluid perceptions of the self too were invested with some meaning? I His Excellency, M. Sevela Naik, Consul General of India at Munich; Prof. Ger- rit Kloss, Dean, Philosophical Faculty; Prof. Stefan Klonner, Executive Direc- tor, SAI; Professor Gita Dharampal Frick, Head, Department of History, SAI; Dr. -

The Era of Science Enthusiasts in Bengal (1841-1891): Akshayakumar, Vidyasagar and Rajendralala

Indian Journal of History of Science, 47.3 (2012) 375-425 THE ERA OF SCIENCE ENTHUSIASTS IN BENGAL (1841-1891): AKSHAYAKUMAR, VIDYASAGAR AND RAJENDRALALA ARUN KUMAR BISWAS* (Received 14 March 2012) During the nineteenth century, the Indian sub-continent witnessed two distinct outbursts of scientific enthusiasm in Bengal: one led by Rammohun Roy and his compatriots (1820-1840) and the other piloted by Mahendralal Sircar and Eugene Lafont (1860-1910). The intermediate decades were pioneered by the triumvirate: Akshayakumar, Vidyasagar, Rajendralala and a few others. Several scientific journals such as Tattvabodhinī Patrika–, Vivida–rtha Samgraha, Rahasya Sandarbha etc dominated the intellectual environment in the country. Some outstanding scientific books were written in Bengali by the triumvirate.Vidyasagar reformed the science content in the educational curricula. Akshayakumar was a champion in the newly emerging philosophy of science in India. Rajendralala was a colossus in the Asiatic Society, master in geography, archaeology, antiquity studies, various technical sciences, and proposed a scheme for rendering European scientific terms into vernaculars of India. There was a separate Muslim community’s approach to science in the 19th Century India. Key words: Akshayakumar, Botanical Collection, Geography, Muslim Community approach to Science, Phrenology, Rajendralala, Science enthusiasts (1841-1891), Technical Sciences, Triumvirate, Positivism, Vidyasagar INTRODUCTION It can be proposed that the first science movement in India was chiefly concentrated in the city of Calcutta and spanned the period of approximately quarter of a century (1814-39) coinciding with the entry of *Flat 2A, ‘Kamalini’ 69A, Townshend Road, Kolkata-700026 376 INDIAN JOURNAL OF HISTORY OF SCIENCE Rammohun in the city and James Prinsep’s departure from it. -

PACIFIC WORLD Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies

PACIFIC WORLD Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies Third Series Number 14 Fall 2012 TITLE iii The Buddhist Sanskrit Tantras: “The Samādhi of the Plowed Row” James F. Hartzell Center for Mind/Brain Sciences (CIMeC) University of Trento, Italy ABSTRACT This paper presents a discussion of the Buddhist Sanskrit tantras that existed prior to or contemporaneous with the systematic translation of this material into Tibetan. I have searched through the Tohoku University Catalogue of the Tibetan Buddhist canon for the names of authors and translators of the major Buddhist tantric works. With authors, and occasionally with translators, I have where appropriate converted the Tibetan names back to their Sanskrit originals. I then matched these names with the information Jean Naudou has uncov- ered, giving approximate, and sometimes specific, dates for the vari- ous authors and translators. With this information in hand, I matched the data to the translations I have made (for the first time) of extracts from Buddhist tantras surviving in H. P. Śāstrī’s catalogues of Sanskrit manuscripts in the Durbar Library of Nepal, and in the Asiatic Society of Bengal’s library in Calcutta, with some supplemental material from the manuscript collections in England at Oxford, Cambridge, and the India Office Library. The result of this research technique is a prelimi- nary picture of the “currency” of various Buddhist Sanskrit tantras in the eighth to eleventh centuries in India as this material gained popu- larity, was absorbed into the Buddhist canon, commented upon, and translated into Tibetan. I completed this work in 1996, and have not had the opportunity or means to update it since. -

Bodh Gayā in the Cultural Memory of Thailand

Eszter Jakab REMEMBERING ENLIGHTENMENT: BODH GAYĀ IN THE CULTURAL MEMORY OF THAILAND MA Thesis in Cultural Heritage Studies: Academic Research, Policy, Management. Central European University CEU eTD Collection Budapest June 2020 REMEMBERING ENLIGHTENMENT: BODH GAYĀ IN THE CULTURAL MEMORY OF THAILAND by Eszter Jakab (Hungary) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Cultural Heritage Studies: Academic Research, Policy, Management. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner ____________________________________________ Examiner CEU eTD Collection Budapest Month YYYY REMEMBERING ENLIGHTENMENT: BODH GAYĀ IN THE CULTURAL MEMORY OF THAILAND by Eszter Jakab (Hungary) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Cultural Heritage Studies: Academic Research, Policy, Management. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ External Reader CEU eTD Collection Budapest June 2020 REMEMBERING ENLIGHTENMENT: BODH GAYĀ IN THE CULTURAL MEMORY OF THAILAND by Eszter Jakab (Hungary) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European -

N 0 T E S on the Bengal Renaissa-Nce

N 0 T E S on the Bengal Renaissa-nce . People's Publishing House, BOMBAY 4. Publishe·d~ in March, 1946. One Rupee 25334~ 0£ C. 19bo Printed by Sharaf Athar Ali, New Age Printing Press, 190B, Khetwadi Main Road. Bombay 4 and published by him for People's Publishing .House, Raj Bhuvan, Sandhurst Road, Bombay 4. INTRODUCTION This short pamphlet gives no more than the broad frame-work for a study of the Bengal Renaissance from Rammohan Roy to Rabindranath Tagore. The author himself-an eminent Marxist intellectual did not desire its publication at this stage as it is in no sense a detailed study nor is the frame-work indicated here necessarily final or complete. He has agreed to its publication for discussion because at the present crisis in Indian life and thought, it is urgently necessary to uncover the roots of the Bengal Renaissance which moulded the modern Indian mind. Much of that heritage has been lost and forgotten. Much of it has been repudiated and distorted. But it still remains the most powerful influence in moulding current ideas of all schools of social and political thought. We are therefore publishing this pamphlet as a con tribution towards the efforts to bring about a correct and common understanding of the ideas of our own past ideo logical heritage so that we may successfully struggle towards new ideas that will help to liberate our land and build a new life for our people. Bengal was the birth-place of the modern Indian Renaissance. We look to all Bengali intellectuals-irres pective of ideological or political differences-to contribute to the discussion. -

Yoga in the Modern World: the Es Arch for the "Authentic" Practice Grace Heerman University of Puget Sound

University of Puget Sound Sound Ideas Sociology & Anthropology Theses Sociology & Anthropology May 2014 Yoga in the Modern World: The eS arch for the "Authentic" Practice Grace Heerman University of Puget Sound Follow this and additional works at: https://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/csoc_theses Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, and the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Heerman, Grace, "Yoga in the Modern World: The eS arch for the "Authentic" Practice" (2014). Sociology & Anthropology Theses. 5. https://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/csoc_theses/5 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology & Anthropology at Sound Ideas. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology & Anthropology Theses by an authorized administrator of Sound Ideas. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Yoga in the Modern World: The Search for the “Authentic” Practice Grace Heerman Asia 489, Independent Research Project Advisor: Prof. Sunil Kukreja 13 April, 2012 Heerman, 2 Introduction Since its early twentieth century debut into Western consciousness, yoga has quickly gained widespread appeal, resonating in the minds of the health-conscious, freedom-seeking American public. Considered to be the “spiritual capital” with which India hoped to garner material and financial support from the West, yoga was originally presented by its Eastern disseminators as “an antidote to the stresses of modern, urban, industrial life” and “a way to reconnect with the spiritual world” without having to compromise the “productive capitalist base upon which Americans [stake] their futures.”1 Though exact practitioner statistics are hard to come by, it is clear that the popularity of yoga in the U.S. -

The National Library of India

THE ~AT I O~AL LIB JCARY tlF INDIA SOUVE:\IR J3 VOLUL\IE 19.5 .'J THE NATIONAL LIBRARY OF INDIA Golden Jubilee .Souvenir Sunday, lst~ebruary,1953 " c!J. do not want m!J houoe to &e waffeJ in on aff oideo and m!J window& to Se otu{{ed. c!J. want cuftureo of aff fando to · te tfown aBout m!J Aouoe a& /reeft; ao poooitle. GJ3ut c!J. re{uoe to 8e tfown o{f ml.J /eet t~J antJ."-MAHATMA GANDHI PRINTED BY THE MANAGER GOVERNMENT OF INDIA PRESS, CALCUTTA, INDIA, 1953 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Foreword 1. History, growth and future of the National Library I 2. Brief history of Belvedere • '. 5 3. Perspective in time • 6 4. List of Chairmen, members and secretaries 8 S. The National Library forty years ago ., • 11 6. The Bibliography of Indology • 16 7. Towards a Basic Bibliography on Indology 21 8. The Section on ancient Indian history and culture 26 9. The Section on Sanskrit, Pali and Prakri\ 30 10. A short account of the Bubar Library 47. 11. List of Librarians 51 12. The Senior Staff of the National Library .· 51 13. Publications of the Library .51 14. In Memoriam . 52 15. Our Thanks 53 16. An ••tract from the "Englishman", Saturday, January 31st 1903 54 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS CoVEll PAGE ! NOilTHERN CoRRIDOR OF THE STACK ROOM FRONTISPIECE :-i _Lo_r~ c'""ur:_on who ln~uguratcd the lmpcrloillbiilrYJ Plate I. Picture of Belvedere Mansion Between pages 10 and 11 .. 2 • Periodical Room .. .. 3. Card Cabinet Room . -

Colonialism & Cultural Identity: the Making of A

COLONIALISM & CULTURAL IDENTITY: THE MAKING OF A HINDU DISCOURSE, BENGAL 1867-1905. by Indira Chowdhury Sengupta Thesis submitted to. the Faculty of Arts of the University of London, for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Oriental and African Studies, London Department of History 1993 ProQuest Number: 10673058 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673058 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT This thesis studies the construction of a Hindu cultural identity in the late nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries in Bengal. The aim is to examine how this identity was formed by rationalising and valorising an available repertoire of images and myths in the face of official and missionary denigration of Hindu tradition. This phenomenon is investigated in terms of a discourse (or a conglomeration of discursive forms) produced by a middle-class operating within the constraints of colonialism. The thesis begins with the Hindu Mela founded in 1867 and the way in which this organisation illustrated the attempt of the Western educated middle-class at self- assertion. -

Scott of Bengal”: Examining the European Legacy in the Historical Novels of Bankimchandra Chatterjee

“Scott of Bengal”: Examining the European Legacy in the Historical Novels of Bankimchandra Chatterjee Nilanjana Dutta A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department English and Comparative Literature Chapel Hill 2009 Approved by: Sucheta Mazumdar John McGowan Eric Downing Srinivas Aravamudan Tony Stewart ABSTRACT Nilanjana Dutta: “Scott of Bengal”: Examining the European Legacy in the Historical Novels of Bankimchandra Chatterjee (Under the direction of Sucheta Mazumdar) It is generally agreed that the novel is of European origin and that it was imported into non-European countries through colonial contact. While acknowledging this European precedence, it is important to also acknowledge the unique ways in which non- European authors indigenized the form to respond to the needs of their contemporary readers who were their intended audience. The works of the nineteenth-century Indian novelist Bankimchandra Chatterjee are a case in point. This dissertation focuses on the role the historical novels of Bankim performed in determining Indian identities at a particular juncture in Indian colonial history. A comparative study with selected novels of Sir Walter Scott, the premier historical novelist of Europe, helps illustrate the singularity of Bankim’s task; Scott and Bankim occupied quite different worlds and their works serve as metaphors of this difference. As the first successful novelist of India, Bankim took on the task of invoking history to create a national identity for a people who, he felt, did not have one. This identity had to be imagined through complex negotiations of race, religion, and gender, each of which required constant redefining. -

Religious Reformation in Bengal Renaissance

MARBURG JOURNAL OF RELIGION, Vol. 22, No. 2 (2020) 1 Religious Reformation in the Bengal Renaissance: Prelude to Science Museums in India Lyric Banerjee Research Fellow, The Asiatic Society In the history of mankind, “the Renaissance” signifies more than the period in European intellectual history with which it is commonly associated. It signifies the expansion of both mental and geographical horizons, and a free-spirited approach towards inventions which encouraged men to accept new ideas and to challenge old ideas and customs while rejecting subservience to fate. While the European Renaissance predates the modern sciences, the “Renaissance approach” is still perceived as a precondition for the inquisitive search for new knowledge that is associated with modern empirical sciences. The popular image of the European Renaissance is thus of a period when knowledge began to blossom. Europe was throbbing with passion for knowledge of the arts, as well as of the natural sciences. The present chapter intends to employ the concept of “Renaissance” to highlight the preconditions for the development of science museums in India, where the intimate relationship between traditional belief and scientific enlightenment appears to have played an important role. This specific amalgamation can be termed as a notion of a new awakening or “Renaissance” which was the guiding force behind the growth of the Indian museums. I have analysed all these developments through surveys of leading Indian public intellectuals, and literature reviews on science exhibitions in museums of colonial India. Also associated with “Renaissance” is the notion that people learnt to discover their inner being and their own worth, and therefore started taking more and more interest in whatever is human. -

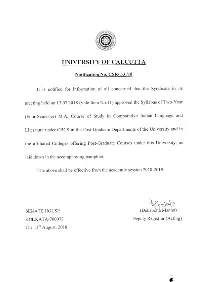

Department of Comparative Indian Language and Literature (CILL) CSR

Department of Comparative Indian Language and Literature (CILL) CSR 1. Title and Commencement: 1.1 These Regulations shall be called THE REGULATIONS FOR SEMESTERISED M.A. in Comparative Indian Language and Literature Post- Graduate Programme (CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM) 2018, UNIVERSITY OF CALCUTTA. 1.2 These Regulations shall come into force with effect from the academic session 2018-2019. 2. Duration of the Programme: The 2-year M.A. programme shall be for a minimum duration of Four (04) consecutive semesters of six months each/ i.e., two (2) years and will start ordinarily in the month of July of each year. 3. Applicability of the New Regulations: These new regulations shall be applicable to: a) The students taking admission to the M.A. Course in the academic session 2018-19 b) The students admitted in earlier sessions but did not enrol for M.A. Part I Examinations up to 2018 c) The students admitted in earlier sessions and enrolled for Part I Examinations but did not appear in Part I Examinations up to 2018. d) The students admitted in earlier sessions and appeared in M.A. Part I Examinations in 2018 or earlier shall continue to be guided by the existing Regulations of Annual System. 4. Attendance 4.1 A student attending at least 75% of the total number of classes* held shall be allowed to sit for the concerned Semester Examinations subject to fulfilment of other conditions laid down in the regulations. 4.2 A student attending at least 60% but less than 75% of the total number of classes* held shall be allowed to sit for the concerned Semester Examinations subject to the payment of prescribed condonation fees and fulfilment of other conditions laid down in the regulations. -

Memory of the World Register

MEMORY OF THE WORLD REGISTER लघकालचकर्तन्तर्राजटीकाु (िवमलपर्भा) laghukālacakratantrarājatikā (Vimalaprabhā) (India) Ref N° 2010-63 PART A – ESSENTIAL INFORMATION 1 SUMMARY Laghukālacakratantrarājatikā (Vimalaprabhā) is the most important Commentary of the Kālacakra Tantra. Within the śramana tradition of Indian culture, Tantric lineage has its own importance. It has, since ancient times, influenced the religion and culture of many countries of Asia. New cultures have also evolved in the wake of Buddhist and Tantric view of life and existence. Buddhist Tantra is an important part of Mahāyāna Buddhism. The Mahāyāna lineage holds that Buddhist Tantras were delivered by the Buddha himself. Buddhist Tantrik literature is both vast and extensive, and the Kālacakra Tantra is a distinguished paradigm among them. It comprehends Āyurveda, Jyotisa, and canons of arts, besides a host of other domains of knowledge and practice. It was on this Tantra that the King Pundarīka, one of the thirty-two Kings of Shambhala, had composed the great commentary named Vimalaprabhā, in the ninth century C.E. In ancient times there were a large number of manuscripts of Kālacakra Tantra and its commentaries in India. But as Buddhism disappeared from India during the twelfth and thirteenth century C.E., a large body of Buddhist literature too went into oblivion. Many of the literary creations went away to neighbouring countries and regions such as Nepal and Tibet. In the nineteenth century C.E., when European scholars commenced their studies in Buddhism, they came across abundant literary materials in Nepal. B. H. Hodgson, an English administrator, ethnologist and a resident at the royal court of Nepal, bequeathed 144 manuscripts to the Asiatic Society, Kolkata with a view to preserving them.