3. American Memories of Madame Curie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 the Equation of a Light Leptonic Magnetic Monopole and Its

The equation of a Light Leptonic Magnetic Monopole and its Experimental Aspects Georges Lochak Fondation Louis de Broglie 23, rue Marsoulan F-75012 Paris [email protected] Abstract. The present theory is closely related to Dirac’s equation of the electron, but not to his magnetic monopole theory, except for his relation between electric and magnetic charge. The theory is based on the fact, that the massless Dirac equation admits a second electromagnetic coupling, deduced from a pseudo-scalar gauge invariance. The equation thus obtained has the symmetry laws of a massless leptonic, magnetic monopole, able to interact weakly. We give a more precise form of the Dirac relation between electric and magnetic charges and a quantum form of the Poincaré first integral. In the Weyl representation our equation splits into P-conjugated monopole and antimonopole equations with the correct electromagnetic coupling and opposite chiralities, predicted by P. Curie. Charge conjugated monopoles are symmetric in space and not in time (contrary to the electric particles) : an important fact for the vacuum polarization. Our monopole is a magnetically excited neutrino, which leads to experimental consequences. These monopoles are assumed to be produced by electromagnetic pulses or arcs, leading to nuclear transmutations and, for beta radioactive elements, a shortening of the life time and the emission of monopoles instead of neutrinos in a magnetic field. A corresponding discussion is given in section 15. 1. Introduction. The hypothesis of separated magnetic poles is very old. In the 2nd volume of his famous Treatise of Electricity and Magnetism [1], devoted to Magnetism, Maxwell considered the existence of free magnetic charges as an evidence, just as the evidence of electric charges. -

Alfred Nobel

www.bibalex.org/bioalex2004conf The BioVisionAlexandria 2004 Conference Newsletter November 2003 Volume 1, Issue 2 BioVisionAlexandria ALFRED NOBEL 2004 aims to celebrate the The inventor, the industrialist outstanding scientists and scholars, in a he Nobel Prize is one of the highest distinctions recognized, granting its winner century dominated by instant fame. However, many do not know the interesting history and background technological and T that led to this award. scientific revolutions, through its It all began with a chemist, known as Alfred Nobel, born in Stockholm, Sweden in 1833. Nobel Day on 3 April Alfred Nobel moved to Russia when he was eight, where his father, Immanuel Nobel, 2004! started a successful mechanical workshop. He provided equipment for the Russian Army and designed naval mines, which effectively prevented the British Royal Navy from moving within firing range of St. Petersburg during the Crimean War. Immanuel Nobel was also a pioneer in the manufacture of arms, and in designing steam engines. INSIDE Scientific awards .........3 Immanuel’s success enabled him to Alfred met Ascanio Sobrero, the Italian Confirmed laureates ....4 Lady laureates ............7 provide his four sons with an excellent chemist who had invented Nitroglycerine education in natural sciences, languages three years earlier. Nitroglycerine, a and literature. Alfred, at an early age, highly explosive liquid, was produced by acquired extensive literary knowledge, mixing glycerine with sulfuric and nitric mastering many foreign languages. His acid. It was an invention that triggered a Nobel Day is interest in science, especially chemistry, fascination in the young scientist for many dedicated to many of was also apparent. -

Unerring in Her Scientific Enquiry and Not Afraid of Hard Work, Marie Curie Set a Shining Example for Generations of Scientists

Historical profile Elements of inspiration Unerring in her scientific enquiry and not afraid of hard work, Marie Curie set a shining example for generations of scientists. Bill Griffiths explores the life of a chemical heroine SCIENCE SOURCE / SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY LIBRARY PHOTO SCIENCE / SOURCE SCIENCE 42 | Chemistry World | January 2011 www.chemistryworld.org On 10 December 1911, Marie Curie only elements then known to or ammonia, having a water- In short was awarded the Nobel prize exhibit radioactivity. Her samples insoluble carbonate akin to BaCO3 in chemistry for ‘services to the were placed on a condenser plate It is 100 years since and a chloride slightly less soluble advancement of chemistry by the charged to 100 Volts and attached Marie Curie became the than BaCl2 which acted as a carrier discovery of the elements radium to one of Pierre’s electrometers, and first person ever to win for it. This they named radium, and polonium’. She was the first thereby she measured quantitatively two Nobel prizes publishing their results on Boxing female recipient of any Nobel prize their radioactivity. She found the Marie and her husband day 1898;2 French spectroscopist and the first person ever to be minerals pitchblende (UO2) and Pierre pioneered the Eugène-Anatole Demarçay found awarded two (she, Pierre Curie and chalcolite (Cu(UO2)2(PO4)2.12H2O) study of radiactivity a new atomic spectral line from Henri Becquerel had shared the to be more radioactive than pure and discovered two new the element, helping to confirm 1903 physics prize for their work on uranium, so reasoned that they must elements, radium and its status. -

Progressing Toward Gender- Responsive Science and Technology*

United Nations Nations Unies United Nations Commission on the Status of Women Fifty-fifth session 22 February – 4 March 2011 New York INTERACTIVE EXPERT PANEL Key policy initiatives and capacity-building on gender mainstreaming: focus on science and technology PROGRESSING TOWARD GENDER- RESPONSIVE SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY* by LONDA SCHIEBINGER Professor Stanford University *The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the United Nations. This paper presents key findings and recommendations from the expert group meeting (EGM) on Gender, Science and Technology, Paris, France, 28 September-1 October 2010.1 The potential of science and technology (S&T) to advance development and contribute to people’s well-being has been well-recognized. Science and technology are vital for achieving internationally agreed-upon development goals, for instance by facilitating efforts to eradicate poverty, achieve food security, fight diseases, improve education, and respond to the challenges of climate change. S&T have also emerged as important means for countries to improve productivity and competitiveness and to create decent work opportunities. The contribution of science and technology to development goals can be accelerated by taking gender into account. For example, greater access to and use of existing technologies, as well as products that respond better to women’s needs, can enhance women’s work. Acquiring science and technology education and training can empower women. Eliminating barriers to women’s employment in science and technology fields will further the goals of full employment and decent work. The EGM covered a wide range of issues related to the intersection of sex and gender with S&T. -

A Century of X-Ray Crystallography and 2014 International Year of X-Ray Crystallography

Macedonian Journal of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Vol. 34, No. 1, pp. 19–32 (2015) MJCCA9 – 658 ISSN 1857-5552 Received: January 15, 2015 UDC: 631.416.865(497.7:282) Accepted: February 13, 2015 Review A CENTURY OF X-RAY CRYSTALLOGRAPHY AND 2014 INTERNATIONAL YEAR OF X-RAY CRYSTALLOGRAPHY Biserka Kojić-Prodić Rudjer Bošković Institute, Bijenička c. 54, Zagreb, Croatia [email protected] The 100th anniversary of the Nobel prize awarded to Max von Laue in 1914 for his discovery of diffraction of X-rays on a crystal marked the beginning of a new branch of science - X-ray crystallog- raphy. The experimental evidence of von Laue's discovery was provided by physicists W. Friedrich and P. Knipping in 1912. In the same year, W. L. Bragg described the analogy between X-rays and visible light and formulated the Bragg's law, a fundamental relation that connected the wave nature of X-rays and fine structure of a crystal at atomic level. In 1913 the first simple diffractometer was constructed and structure determination started by the Braggs, father and son. In 1915 their discoveries were acknowl- edged by a Nobel Prize in physics. Since then, X-ray diffraction has been the basic method for determina- tion of three-dimensional structures of synthetic and natural compounds. The three-dimensional structure of a substances defines its physical, chemical, and biological properties. Over the past century the signifi- cance of X-ray crystallography has been recognized by about forty Nobel prizes. X-ray structure analysis of simple crystals of rock salt, diamond and graphite, and later of complex biomolecules such as B12- vitamin, penicillin, haemoglobin/myoglobin, DNA, and biomolecular complexes such as viruses, chroma- tin, ribozyme, and other molecular machines have illustrated the development of the method. -

Wolfgang Pauli Niels Bohr Paul Dirac Max Planck Richard Feynman

Wolfgang Pauli Niels Bohr Paul Dirac Max Planck Richard Feynman Louis de Broglie Norman Ramsey Willis Lamb Otto Stern Werner Heisenberg Walther Gerlach Ernest Rutherford Satyendranath Bose Max Born Erwin Schrödinger Eugene Wigner Arnold Sommerfeld Julian Schwinger David Bohm Enrico Fermi Albert Einstein Where discovery meets practice Center for Integrated Quantum Science and Technology IQ ST in Baden-Württemberg . Introduction “But I do not wish to be forced into abandoning strict These two quotes by Albert Einstein not only express his well more securely, develop new types of computer or construct highly causality without having defended it quite differently known aversion to quantum theory, they also come from two quite accurate measuring equipment. than I have so far. The idea that an electron exposed to a different periods of his life. The first is from a letter dated 19 April Thus quantum theory extends beyond the field of physics into other 1924 to Max Born regarding the latter’s statistical interpretation of areas, e.g. mathematics, engineering, chemistry, and even biology. beam freely chooses the moment and direction in which quantum mechanics. The second is from Einstein’s last lecture as Let us look at a few examples which illustrate this. The field of crypt it wants to move is unbearable to me. If that is the case, part of a series of classes by the American physicist John Archibald ography uses number theory, which constitutes a subdiscipline of then I would rather be a cobbler or a casino employee Wheeler in 1954 at Princeton. pure mathematics. Producing a quantum computer with new types than a physicist.” The realization that, in the quantum world, objects only exist when of gates on the basis of the superposition principle from quantum they are measured – and this is what is behind the moon/mouse mechanics requires the involvement of engineering. -

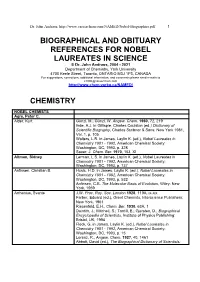

Biographical References for Nobel Laureates

Dr. John Andraos, http://www.careerchem.com/NAMED/Nobel-Biographies.pdf 1 BIOGRAPHICAL AND OBITUARY REFERENCES FOR NOBEL LAUREATES IN SCIENCE © Dr. John Andraos, 2004 - 2021 Department of Chemistry, York University 4700 Keele Street, Toronto, ONTARIO M3J 1P3, CANADA For suggestions, corrections, additional information, and comments please send e-mails to [email protected] http://www.chem.yorku.ca/NAMED/ CHEMISTRY NOBEL CHEMISTS Agre, Peter C. Alder, Kurt Günzl, M.; Günzl, W. Angew. Chem. 1960, 72, 219 Ihde, A.J. in Gillispie, Charles Coulston (ed.) Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Charles Scribner & Sons: New York 1981, Vol. 1, p. 105 Walters, L.R. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 328 Sauer, J. Chem. Ber. 1970, 103, XI Altman, Sidney Lerman, L.S. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 737 Anfinsen, Christian B. Husic, H.D. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 532 Anfinsen, C.B. The Molecular Basis of Evolution, Wiley: New York, 1959 Arrhenius, Svante J.W. Proc. Roy. Soc. London 1928, 119A, ix-xix Farber, Eduard (ed.), Great Chemists, Interscience Publishers: New York, 1961 Riesenfeld, E.H., Chem. Ber. 1930, 63A, 1 Daintith, J.; Mitchell, S.; Tootill, E.; Gjersten, D., Biographical Encyclopedia of Scientists, Institute of Physics Publishing: Bristol, UK, 1994 Fleck, G. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 15 Lorenz, R., Angew. -

Ion Trap Nobel

The Nobel Prize in Physics 2012 Serge Haroche, David J. Wineland The Nobel Prize in Physics 2012 was awarded jointly to Serge Haroche and David J. Wineland "for ground-breaking experimental methods that enable measuring and manipulation of individual quantum systems" David J. Wineland, U.S. citizen. Born 1944 in Milwaukee, WI, USA. Ph.D. 1970 Serge Haroche, French citizen. Born 1944 in Casablanca, Morocco. Ph.D. from Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA. Group Leader and NIST Fellow at 1971 from Université Pierre et Marie Curie, Paris, France. Professor at National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and University of Colorado Collège de France and Ecole Normale Supérieure, Paris, France. Boulder, CO, USA www.college-de-france.fr/site/en-serge-haroche/biography.htm www.nist.gov/pml/div688/grp10/index.cfm A laser is used to suppress the ion’s thermal motion in the trap, and to electrode control and measure the trapped ion. lasers ions Electrodes keep the beryllium ions inside a trap. electrode electrode Figure 2. In David Wineland’s laboratory in Boulder, Colorado, electrically charged atoms or ions are kept inside a trap by surrounding electric fields. One of the secrets behind Wineland’s breakthrough is mastery of the art of using laser beams and creating laser pulses. A laser is used to put the ion in its lowest energy state and thus enabling the study of quantum phenomena with the trapped ion. Controlling single photons in a trap Serge Haroche and his research group employ a diferent method to reveal the mysteries of the quantum world. -

Nobel Prizes Social Network

Nobel prizes social network Marie Skłodowska Curie (Phys.1903, Chem.1911) Nobel prizes social network Henri Becquerel (Phys.1903) Pierre Curie (Phys.1903) = Marie Skłodowska Curie (Phys.1903, Chem.1911) Nobel prizes social network Henri Becquerel (Phys.1903) Pierre Curie (Phys.1903) = Marie Skłodowska Curie (Phys.1903, Chem.1911) Irène Joliot-Curie (Chem.1935) Nobel prizes social network Henri Becquerel (Phys.1903) Pierre Curie (Phys.1903) = Marie Skłodowska Curie (Phys.1903, Chem.1911) Irène Joliot-Curie (Chem.1935) = Frédéric Joliot-Curie (Chem.1935) Nobel prizes social network Henri Becquerel (Phys.1903) Pierre Curie (Phys.1903) = Marie Skłodowska Curie (Phys.1903, Chem.1911) Paul Langevin Irène Joliot-Curie (Chem.1935) = Frédéric Joliot-Curie (Chem.1935) Nobel prizes social network Henri Becquerel (Phys.1903) Pierre Curie (Phys.1903) = Marie Skłodowska Curie (Phys.1903, Chem.1911) Paul Langevin Maurice de Broglie Louis de Broglie (Phys.1929) Irène Joliot-Curie (Chem.1935) = Frédéric Joliot-Curie (Chem.1935) Nobel prizes social network Sir J. J. Thomson (Phys.1906) Henri Becquerel (Phys.1903) Pierre Curie (Phys.1903) = Marie Skłodowska Curie (Phys.1903, Chem.1911) Paul Langevin Maurice de Broglie Louis de Broglie (Phys.1929) Irène Joliot-Curie (Chem.1935) = Frédéric Joliot-Curie (Chem.1935) Nobel prizes social network (more) Sir J. J. Thomson (Phys.1906) Nobel prizes social network (more) Sir J. J. Thomson (Phys.1906) Owen Richardson (Phys.1928) Nobel prizes social network (more) Sir J. J. Thomson (Phys.1906) Owen Richardson (Phys.1928) Clinton Davisson (Phys.1937) Nobel prizes social network (more) Sir J. J. Thomson (Phys.1906) Owen Richardson (Phys.1928) Charlotte Richardson = Clinton Davisson (Phys.1937) Nobel prizes social network (more) Sir J. -

Richard P. Feynman Author

Title: The Making of a Genius: Richard P. Feynman Author: Christian Forstner Ernst-Haeckel-Haus Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena Berggasse 7 D-07743 Jena Germany Fax: +49 3641 949 502 Email: [email protected] Abstract: In 1965 the Nobel Foundation honored Sin-Itiro Tomonaga, Julian Schwinger, and Richard Feynman for their fundamental work in quantum electrodynamics and the consequences for the physics of elementary particles. In contrast to both of his colleagues only Richard Feynman appeared as a genius before the public. In his autobiographies he managed to connect his behavior, which contradicted several social and scientific norms, with the American myth of the “practical man”. This connection led to the image of a common American with extraordinary scientific abilities and contributed extensively to enhance the image of Feynman as genius in the public opinion. Is this image resulting from Feynman’s autobiographies in accordance with historical facts? This question is the starting point for a deeper historical analysis that tries to put Feynman and his actions back into historical context. The image of a “genius” appears then as a construct resulting from the public reception of brilliant scientific research. Introduction Richard Feynman is “half genius and half buffoon”, his colleague Freeman Dyson wrote in a letter to his parents in 1947 shortly after having met Feynman for the first time.1 It was precisely this combination of outstanding scientist of great talent and seeming clown that was conducive to allowing Feynman to appear as a genius amongst the American public. Between Feynman’s image as a genius, which was created significantly through the representation of Feynman in his autobiographical writings, and the historical perspective on his earlier career as a young aspiring physicist, a discrepancy exists that has not been observed in prior biographical literature. -

More Eugene Wigner Stories; Response to a Feynman Claim (As Published in the Oak Ridger’S Historically Speaking Column on August 29, 2016)

More Eugene Wigner stories; Response to a Feynman claim (As published in The Oak Ridger’s Historically Speaking column on August 29, 2016) Carolyn Krause has collected a couple more stories about Eugene Wigner, plus a response by Y- 12 to allegations by Richard Feynman in a book that included a story on his experience at Y-12 during World War II. … Mary Ann Davidson, widow of Jack Davidson, a longtime member of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory’s Instrumentation and Controls Division, told me about Jack’s encounter with Wigner one day. Once Eugene Wigner had trouble opening his briefcase while visiting ORNL. He was referred to Jack Davidson in the old Instrumentation and Controls Division. Jack managed to open it for him. As was his custom, Wigner asked Jack about his research. Jack, who later won an R&D-100 award, said he was building a camera that will imitate a fly’s eye; in other words, it will capture light coming from a variety of directions. The topic of television and TV cameras came up. Wigner said he wondered how TV works. So Davidson explained the concept to him. Charles Jones told me this story about Eugene Wigner when he visited ORNL in the 1980s. Jones, who was technical director of the Holifield Heavy Ion Research Facility, said he invited Wigner to accompany him to the top of the HHIRF tower, and Wigner happily accepted the offer. At the top Wigner looked down at all the ORNL buildings, most of which had been constructed after he was the lab’s research director in 1946-47. -

Science Foundation Ss

CONFERENCE REPORT WOMEN &SCIENCE CELEBRATING ACHIEVEMENTS, CHARTING CHALLENGES NATIONAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION Women & Science Celebrating Achievements Charting Challenges Conference Report March 1997 National Science Foundation 4201 Wilson Boulevard Arlington, VA 22230 http://www.ehr.nsf.gov/conferences/women95.htm The material presented in this report constitutes a summary of the views and opinions of those who participated in the Women & Science conference. In particular, the summaries of the various breakout sessions and the sidebars containing opinions of individual conference participants do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. ii Table of Contents Executive Summary...................................................................................................v Statement from the Deputy Director of the National Science Foundation.........vii The Conference About the Conference and This Report..................................................................1 Disciplinary Breakout Sessions Biological Sciences ...............................................................................................5 Computer and Information Science and Engineering....................................10 Engineering ........................................................................................................15 Geosciences and Polar Programs ......................................................................20 Mathematical and Physical Sciences .................................................................25