Dallas Love Field: the Wright and Shelby Amendments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DOMESTIC AVIATION: Changes in Airfares, Service, and Safety

United States General Accounting Office Testimony GAO Before the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation, U.S. Senate For Release on Delivery DOMESTIC AVIATION Expected at 9:30 a.m. EDT Thursday, April 25, 1996 Changes in Airfares, Service, and Safety Since Airline Deregulation Statement of John H. Anderson, Jr., Director, Transportation and Telecommunications Issues, Resources, Community, and Economic Development Division GOA years 1921 - 1996 GAO/T-RCED-96-126 Mr. Chairman and Members of the Committee: We appreciate the opportunity to testify on the changes that have occurred in domestic aviation since the deregulation of the airline industry. The Airline Deregulation Act of 1978 phased out the federal government’s control over airfares and service, relying instead on competitive market forces to decide the price, quantity, and quality of domestic air service. Our testimony today discusses the findings of our report, prepared at the request of this Committee and being released today, in which we compared the changes in airline (1) fares, (2) service quantity and quality, and (3) safety since deregulation for airports serving small, medium-sized, and large communities.1 In summary, we found the following: • Fares per passenger mile, adjusted for inflation, have fallen since deregulation about as much at airports serving small and medium-sized communities as they have at airports serving large communities. A key factor contributing to the overall trend toward lower airfares has been the increased competition spurred by the entry of new low-cost, low-fare airlines, especially at airports in the West and Southwest. Nevertheless, some airports—particularly those serving small and medium-sized communities in the Southeast and in the Appalachian region—have experienced substantial increases in fares since deregulation. -

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ARMYAIR AAC Army Air Corps United Kingdom Civil AgustaWestland Lynx AH.9A/AW159 Wildcat ARMYAIR 200# AAC 2Regt | AAC AH.1 AAC Middle Wallop United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 300# AAC 3Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 400# AAC 4Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 500# AAC 5Regt AAC/RAF Britten-Norman Islander/Defender JHCFS Aldergrove United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 600# AAC 657Sqn | JSFAW | AAC Various RAF Odiham United Kingdom Military Ambassador AAD Mann Air Ltd United Kingdom Civil AIGLE AZUR AAF ZI Aigle Azur France Civil ATLANTIC AAG KI Air Atlantique United Kingdom Civil ATLANTIC AAG Atlantic Flight Training United Kingdom Civil ALOHA AAH KH Aloha Air Cargo United States Civil BOREALIS AAI Air Aurora United States Civil ALFA SUDAN AAJ Alfa Airlines Sudan Civil ALASKA ISLAND AAK Alaska Island Air United States Civil AMERICAN AAL AA American Airlines United States Civil AM CORP AAM Aviation Management Corporation United States Civil -

Airline Schedules

Airline Schedules This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on January 08, 2019. English (eng) Describing Archives: A Content Standard Special Collections and Archives Division, History of Aviation Archives. 3020 Waterview Pkwy SP2 Suite 11.206 Richardson, Texas 75080 [email protected]. URL: https://www.utdallas.edu/library/special-collections-and-archives/ Airline Schedules Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Series Description .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 5 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 - Page 2 - Airline Schedules Summary Information Repository: -

Overview and Trends

9310-01 Chapter 1 10/12/99 14:48 Page 15 1 M Overview and Trends The Transportation Research Board (TRB) study committee that pro- duced Winds of Change held its final meeting in the spring of 1991. The committee had reviewed the general experience of the U.S. airline in- dustry during the more than a dozen years since legislation ended gov- ernment economic regulation of entry, pricing, and ticket distribution in the domestic market.1 The committee examined issues ranging from passenger fares and service in small communities to aviation safety and the federal government’s performance in accommodating the escalating demands on air traffic control. At the time, it was still being debated whether airline deregulation was favorable to consumers. Once viewed as contrary to the public interest,2 the vigorous airline competition 1 The Airline Deregulation Act of 1978 was preceded by market-oriented administra- tive reforms adopted by the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) beginning in 1975. 2 Congress adopted the public utility form of regulation for the airline industry when it created CAB, partly out of concern that the small scale of the industry and number of willing entrants would lead to excessive competition and capacity, ultimately having neg- ative effects on service and perhaps leading to monopolies and having adverse effects on consumers in the end (Levine 1965; Meyer et al. 1959). 15 9310-01 Chapter 1 10/12/99 14:48 Page 16 16 ENTRY AND COMPETITION IN THE U.S. AIRLINE INDUSTRY spurred by deregulation now is commonly credited with generating large and lasting public benefits. -

Appendix C Informal Complaints to DOT by New Entrant Airlines About Unfair Exclusionary Practices March 1993 to May 1999

9310-08 App C 10/12/99 13:40 Page 171 Appendix C Informal Complaints to DOT by New Entrant Airlines About Unfair Exclusionary Practices March 1993 to May 1999 UNFAIR PRICING AND CAPACITY RESPONSES 1. Date Raised: May 1999 Complaining Party: AccessAir Complained Against: Northwest Airlines Description: AccessAir, a new airline headquartered in Des Moines, Iowa, began service in the New York–LaGuardia and Los Angeles to Mo- line/Quad Cities/Peoria, Illinois, markets. Northwest offers connecting service in these markets. AccessAir alleged that Northwest was offering fares in these markets that were substantially below Northwest’s costs. 171 9310-08 App C 10/12/99 13:40 Page 172 172 ENTRY AND COMPETITION IN THE U.S. AIRLINE INDUSTRY 2. Date Raised: March 1999 Complaining Party: AccessAir Complained Against: Delta, Northwest, and TWA Description: AccessAir was a new entrant air carrier, headquartered in Des Moines, Iowa. In February 1999, AccessAir began service to New York–LaGuardia and Los Angeles from Des Moines, Iowa, and Moline/ Quad Cities/Peoria, Illinois. AccessAir offered direct service (nonstop or single-plane) between these points, while competitors generally offered connecting service. In the Des Moines/Moline–Los Angeles market, Ac- cessAir offered an introductory roundtrip fare of $198 during the first month of operation and then planned to raise the fare to $298 after March 5, 1999. AccessAir pointed out that its lowest fare of $298 was substantially below the major airlines’ normal 14- to 21-day advance pur- chase fares of $380 to $480 per roundtrip and was less than half of the major airlines’ normal 7-day advance purchase fare of $680. -

Airline Deregulation - Only Partially a Hoax: the Current Status of the Airline Deregulation Movement James W

Journal of Air Law and Commerce Volume 45 | Issue 4 Article 7 1980 Airline Deregulation - Only Partially a Hoax: The Current Status of the Airline Deregulation Movement James W. Callison Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc Recommended Citation James W. Callison, Airline Deregulation - Only Partially a Hoax: The Current Status of the Airline Deregulation Movement, 45 J. Air L. & Com. 961 (1980) https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc/vol45/iss4/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Air Law and Commerce by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. AIRLINE DEREGULATION-ONLY PARTIALLY A HOAX: THE CURRENT STATUS OF THE AIRLINE DEREGULATION MOVEMENT JAMES W. CALLISON, ESQ.* I. INTRODUCTION N 1975, LONG before any legislation was passed, I wrote an article addressing various airline economic deregulation pro- posals setting forth a number of reasons why extensive deregula- tion was not necessary to achieve the professed goals of its sup- porters.! In short, I put forth the thesis that arguments for airline deregulation might be a hoax, because: (1) the prior Federal Aviation Act2 was already procompetitive and, with the enlightened application which it had generally received, had fostered extensive although not unfettered competition; (2) the former law also provided for price competition and, while the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB or the Board) had not been as liberal in this respect as it had been concerning route competition, there was consider- able price competition in the airline industry with Americans en- joying the world's lowest airline passenger fares and air freight rates; and (3) the former statute also guarded against the other major ghost seen by the deregulators at that time, i.e., the specter of anticompetitive agreements and practices adverse to the public interest.' * Senior Vice President-General Counsel, Delta Air Lines, Inc. -

Political Economy of Hong Kong's Open Skies Legal Regime

The Political Economy of Hong Kong's "Open Skies" Legal Regime: An Empirical and Theoretical Exploration MIRON MUSHKAT* RODA MUSHKAT** TABLE OF CONTENTS I. IN TRO DU CTIO N .................................................................................................. 38 1 II. TOW ARD "O PEN SKIES". .................................................................................... 384 III. H ONG K ONG RESPONSE ..................................................................................... 399 IV. QUEST FOR ANALYTICAL EXPLANATION ............................................................ 410 V. IMPLICATIONS FOR INTERNATIONAL REGIMES .................................................... 429 V 1. C O N CLU SION ..................................................................................................... 4 37 I. INTRODUCTION Hong Kong is widely believed to epitomize the practical virtues of the neoclassical economic model. It consistently outranks other countries in terms of the criteria incorporated into the Heritage Foundation's authoritative Index of Economic Freedom. The periodically challenging and potentially * Adjunct Professor of Economics and Finance, Syracuse University Hong Kong Program. ** Professor of Law and Director of the Center for International and Public Law, Brunel Law School, Brunel University; and Honorary Professor, Faculty of Law, University of Hong Kong. tumultuous transition from British to Chinese rule has thus far had no tangible impact on its status in this respect. A new post-1997 political -

A Free Bird Sings the Song of the Caged: Southwest Airlines' Fight to Repeal the Wright Amendment John Grantham

Journal of Air Law and Commerce Volume 72 | Issue 2 Article 10 2007 A Free Bird Sings the Song of the Caged: Southwest Airlines' Fight to Repeal the Wright Amendment John Grantham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc Recommended Citation John Grantham, A Free Bird Sings the Song of the Caged: Southwest Airlines' Fight to Repeal the Wright Amendment, 72 J. Air L. & Com. 429 (2007) https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc/vol72/iss2/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Air Law and Commerce by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. A FREE BIRD SINGS THE SONG OF THE CAGED: SOUTHWEST AIRLINES' FIGHT TO REPEAL THE WRIGHT AMENDMENT JOHN GRANTHAM* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .................................. 430 II. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND .................... 432 A. THE BATTLE TO ESTABLISH AIRPORTS IN NORTH T EXAS .......................................... 433 B. PLANNING FOR THE SUCCESS OF THE NEW AIRPORT ........................................ 436 C. THE UNEXPECTED BATTLE FOR AIRPORT CONSOLIDATION ................................... 438 III. THE EXCEPTION TO DEREGULATION ......... 440 A. THE DEREGULATION OF AIRLINE TRAVEL ......... 440 B. DEFINING THE WRIGHT AMENDMENT RESTRICTIONS ................................... 444 C. EXPANDING THE WRIGHT AMENDMENT ........... 447 D. SOUTHWEST COMES OUT AGAINST THE LoVE FIELD RESTRICTIONS ............................... 452 E. THE END OF AN ERA OR THE START OF SOMETHING NEW .................................. 453 IV. THE WRIGHT POLICY ............................ 455 A. COMMERCE CLAUSE ................................. 456 B. THE WRIGHT AMENDMENT WILL REMAIN STRONG LAW IF ALLOWED .................................. 456 1. ConstitutionalIssues ......................... 456 2. Deference to Administrative Agency Interpretation............................... -

American Airlines' Actions Raise Predatory Pricing Concerns

American Airlines’ Actions Raise Predatory Pricing Concerns Michael Baye and Patrick Scholten prepared this case to serve as the basis for classroom discussion rather than to represent economic or legal fact. The case is a condensed and slightly modified version of the public copy documents involving case No. 99-1180-JTM initially filed on May 13, 1999 in United States of America v. AMR Corporation, American Airlines, Inc., and AMR Eagle Holding Corporation. INTRODUCTION1 Between 1995 and 1997 American Airlines competed against several low-cost carriers (LCC) on various airline routes centered on the Dallas-Fort Worth Airport. During this period, these low- cost carriers created a new market dynamic charging markedly lower fares on certain routes. For a certain period (of differing length in each market) consumers of air travel on these routes enjoyed lower prices. The number of passengers also substantially increased. American responded to the low cost carriers by reducing some of its own fares, and increasing the number of flights serving the routes. In each instance, the low-cost carrier failed to establish itself as a durable market presence, and eventually moved its operations, or ceased its separate existence entirely. After the low-cost carrier ceased operations, American generally resumed its prior marketing strategy, and in certain markets reduced the number of flights and raised its prices, roughly to levels comparable to those prior to the period of low-fare competition. American's pricing and capacity decisions on the routes in question could have resulted in pricing its product below cost, and American might have intended to subsequently recoup these costs by supra-competitive pricing by monopolizing or attempting to monopolize these routes. -

Deregulation and the Troglodytes - How the Airline Met Adam Smith Herbert D

Journal of Air Law and Commerce Volume 50 | Issue 2 Article 7 1985 Deregulation and the Troglodytes - How the Airline Met Adam Smith Herbert D. Kelleher Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc Recommended Citation Herbert D. Kelleher, Deregulation and the Troglodytes - How the Airline Met Adam Smith, 50 J. Air L. & Com. 299 (1985) https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc/vol50/iss2/7 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Air Law and Commerce by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. DEREGULATION AND THE TROGLODYTES - HOW THE AIRLINES MET ADAM SMITH By HERBERT D. KELLEHER* A LMOST 200 YEARS after his death, Adam Smith's ethereal invisible hand swept across the American air- line industry, brushing aside in its wake a regulatory struc- ture which for forty years had bred the arrogance, slothful inefficiency and unresponsiveness inherent in an industry which has substituted paternal "regulation" by a suppos- edly omniscient regent for the competitive impetus of a free marketplace. Through a single broad stroke, enacted with the support of a newly-enlightened regulatory agency under the leadership of Chairman Alfred Kahn, Congress set the airlines free of the regulatory strictures which had constrained the innovation of service alterna- tives, restricted market entry and discouraged price com- petition. As might be expected of a troupe of competitive troglodytes emerging from the protective cocoon of a reg- ulated existence, some members of the newly liberated sect suffered, and some prospered, while some fell into a boiling caldron.' Because deregulation of the airline industry provided much of the stimulus for a general reevaluation of the be- neficence of economic regulation of other potentially competitive industries (such as communications, 2 truck- *President and Chief Executive Officer, Southwest Airlines Co. -

OCTOBER-DECEMBER 2019 Journal of the International Society of Air Safety Investigators

Air Safety Through Investigation OCTOBER-DECEMBER 2019 Journal of the International Society of Air Safety Investigators ISASI Goes to the Netherlands page 4 ISASI Honors Capt. Akrivos Tsolakis with 2019 Jerome F. Lederer Award page 12 Comparing UA232 and AA383 Uncontained Events page 15 ISASI Kapustin Scholarship Essay—Applying Human Factors to Commercial Space Operations page 20 LAMIA Flight 2933: Who Lived, Who Died, and Why page 23 CONTENTS Air Safety Through Investigation Journal of the International Society of Air Safety Investigators FEATURES Volume 52, Number 4 Publisher Frank Del Gandio 4 ISASI Goes to the Netherlands Editorial Advisor Richard B. Stone By J. Gary DiNunno, Editor, ISASI Forum—ISASI holds its 50th annual seminar in The Editor J. Gary DiNunno Hague, the Netherlands September 3-5. Participants attended technical presentations, Design Editor Jesica Ferry social events, and the traditional awards banquet. The ISASI 2020 host committee discussed Associate Editor Susan Fager plans for the next seminar to be held in Montreal, Que., Canada. ISASI Forum (ISSN 1088-8128) is published quar- terly by the International Society of Air Safety 12 ISASI Honors Capt. Akrivos Tsolakis Investigators. Opinions expressed by authors do with 2019 Jerome F. Lederer Award not necessarily represent official ISASI position or policy. By J. Gary DiNunno, Editor, ISASI Forum—During the ISASI 2019 awards banquet, held in The Hague, the Netherlands, the Society presented its highest recognition for lifetime air Editorial Offices: Park Center, 107 East Holly Ave- safety achievement to Capt. Akrivos Tsolakis, Hellenic Air Accident Investigation & Aviation nue, Suite 11, Sterling, VA 20164-5405. -

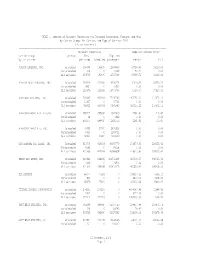

TABLE 1. Summary of Aircraft Departures and Enplaned

TABLE 1. Summary of Aircraft Departures and Enplaned Passengers, Freight, and Mail by Carrier Group, Air Carrier, and Type of Service: 2000 ( Major carriers ) -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Aircraft Departures Enplaned revenue-tones Carrier Group Service Total Enplaned by air carrier performed Scheduled passengers Freight Mail -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ALASKA AIRLINES, INC. Scheduled 158308 165435 12694899 63018.40 19220.01 Nonscheduled 228 0 12409 50.32 0.00 All services 158536 165435 12707308 63068.72 19220.01 AMERICA WEST AIRLINES, INC. Scheduled 204018 212692 19706774 31326.34 35926.29 Nonscheduled 8861 0 9632 0.00 0.00 All services 212879 212692 19716406 31326.34 35926.29 AMERICAN AIRLINES, INC. Scheduled 769485 800908 77205742 367155.22 210672.12 Nonscheduled 21437 0 37701 0.00 0.00 All services 790922 800908 77243443 367155.22 210672.12 AMERICAN EAGLE AIRLINES,INC Scheduled 459247 499830 11623833 2261.84 713.67 Nonscheduled 28 0 1922 0.00 0.00 All services 459275 499830 11625755 2261.84 713.67 AMERICAN TRANS AIR, INC. Scheduled 49496 50210 5830539 0.00 0.00 Nonscheduled 9425 0 1189721 0.00 0.00 All services 58921 50210 7020260 0.00 0.00 CONTINENTAL AIR LINES, INC. Scheduled 413746 419998 40947770 148373.63 128123.41 Nonscheduled 9592 0 41058 0.00 0.00 All services 423338 419998 40988828 148373.63 128123.41 DELTA AIR LINES, INC. Scheduled 916463 946995 101756198 400539.37 346435.53 Nonscheduled 5156 0 74975 0.04 0.00 All services 921619 946995 101831173 400539.41 346435.53 DHL AIRWAYS Scheduled 68777 77823 0 314057.33 5305.19 Nonscheduled 802 0 0 6872.73 3338.03 All services 69579 77823 0 320930.06 8643.22 FEDERAL EXPRESS CORPORATION Scheduled 274215 274215 0 4478347.96 11348.92 Nonscheduled 2927 0 0 6177.09 0.00 All services 277142 274215 0 4484525.05 11348.92 NORTHWEST AIRLINES, INC.