Liberated and Occupied Iraq: New Beginnings and Challenges for Press Freedom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cuaderno De Documentacion

SECRETARIA DE ESTADO DE ECONOMÍA, MINISTERIO DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE POLÍTICA ECONÓMICA DE ECONOMÍA SUBDIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE ECONOMÍA INTERNACIONAL CUADERNO DE DOCUMENTACION Número 43 Alvaro Espina Vocal Asesor 22 de Abril 2003 CUADERNO DE DOCUMENTACIÓN 22042003 43 Guerra de Irak: (VIII) 1.- Foreign Affairs May/June 2003, Vol 82, Number 3. Issue Highlight: “The Rise of Ethics in Foreign Policy: Reaching a Values Consensus” by Leslie H. Gelb and Justine A. Rosenthal "Why the Security Council Failed" by Michael Glennon “How to Build a Democratic Iraq” By Adeed Dawisha and Karen Dawisha “A Trusteeship for Palestine?” Martin Indyk “Is Turkey Ready for Europe?” by Michael S. Teitelbaum and Philip L. Martin ………………………………………………………………………………………Página 3 2.- Informe completo días 10, 11, 14, 16 y 17 de abril - April 17, 2003 MIDEAST ROADMAP: IRAQ WAR OPENS 'WINDOW OF OPPORTUNITY' FOR PEACE .………………………………………….. Página 9 - April 16, 2003 IRAQ: THE HUNT FOR 'STUBBORNLY ELUSIVE' WMD…P. 27 - April 14, 2003 POST-IRAQ: SYRIA IS LIKELY 'NEXT VICTIM' OF U.S. 'IMPERIALISM' ……………………………………………………………Página 40 - April 10, 2003 DEATHS OF JOURNALISTS: SUSPICION U.S. ATTACKS WERE 'NO ACCIDENT' 1,? ……………………………………………...…... Página 61 - April 10, 2003 FALL OF BAGHDAD 'IMPRESSIVE' BUT 'TROUBLING' ………………………………………………………………………... Página 76 3.- Brookings Iraq Reports días 10, 11, 12, 14, 15, 16 y 18 de abril ............................................................. ........................Página 99 1 TheNew National Security Strategy: Focus on Failed States by Susan E. Rice………………………………………………………… Página 111 4.- American Outlook Today, días 15, y 16 de abril …...................................................………… Página 117 5.- San Francisco Chronicle, The pictures of the war ……….................................................................. Página 123 “Plan for democracy in Iraq may be folly. Experts also question U.S. -

Mission Report

International Press Freedom and Freedom of Expression Mission to the Maldives A Vibrant Media Under Pressure: An Independent Assessment of Press Freedom in the Maldives July 2006 Contributing Organisations: Article XIX Reporters without Borders (RSF) International Media Support (IMS) International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) South Asia Press Commission (SAPC) The findings in this report are based on a joint assessment mission to the Maldives in May 2006 19 July 2006 Table of Contents Executive Summary 1. Introduction 2. Background and Media Landscape 3. Intimidation and Harassment 4. House Arrest and Detention 5. Media Law Reforms 6. Recommendations Acroymns and Terminology AP Justice Party/ Adaalath Party Dhivehi Official language of the Maldives DRP Dhivehi Raiyyethunge Party (Maldivian Peoples Party) HRCM Human Rights Commission of the Maldives IDP Islamic Democratic Party Majlis Parliament/ Assembly MDP Maldivian Democratic Party MNDF Maldivian National Defence Force MP Member of Parliament NSS National Security Service of the Maldives SAARC South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation Special Majlis Constitutional Parliament/ Assembly UNDP United Nations Development Programme UNHCHR United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights This report is being made publicly available in the interests of sharing information and enhancing coordination amongst freedom of expression, press freedom and media support actors. All information presented in this report is based on interviews and written contributions provided to the mission members during April and May 2006 and should be independently rechecked by any party seeking to use it as a basis for comment or action. The mission team welcomes all feedback and suggestions from organisations or individuals about the report, which can be sent to the participating organisations (please see contact details at the end of the report). -

DA Spring 03

DangerousAssignments covering the global press freedom struggle Spring | Summer 2003 www.cpj.org Covering the Iraq War Kidnappings in Colombia Committee to·Protect Cannibalizing the Press in Haiti Journalists CONTENTS Dangerous Assignments Spring|Summer 2003 Committee to Protect Journalists FROM THE EDITOR By Susan Ellingwood Executive Director: Ann Cooper History in the making. 2 Deputy Director: Joel Simon IN FOCUS By Amanda Watson-Boles Dangerous Assignments Cameraman Nazih Darwazeh was busy filming in the West Bank. Editor: Susan Ellingwood Minutes later, he was dead. What happened? . 3 Deputy Editor: Amanda Watson-Boles Designer: Virginia Anstett AS IT HAPPENED By Amanda Watson-Boles Printer: Photo Arts Limited A prescient Chinese free-lancer disappears • Bolivian journalists are Committee to Protect Journalists attacked during riots • CPJ appeals to Rumsfeld • Serbia hamstrings Board of Directors the media after a national tragedy. 4 Honorary Co-Chairmen: CPJ REMEMBERS Walter Cronkite Our fallen colleagues in Iraq. 6 Terry Anderson Chairman: David Laventhol COVERING THE IRAQ WAR 8 Franz Allina, Peter Arnett, Tom Why I’m Still Alive By Rob Collier Brokaw, Geraldine Fabrikant, Josh A San Francisco Chronicle reporter recounts his days and nights Friedman, Anne Garrels, James C. covering the war in Baghdad. Goodale, Cheryl Gould, Karen Elliott House, Charlayne Hunter- Was I Manipulated? By Alex Quade Gault, Alberto Ibargüen, Gwen Ifill, Walter Isaacson, Steven L. Isenberg, An embedded CNN reporter reveals who pulled the strings behind Jane Kramer, Anthony Lewis, her camera. David Marash, Kati Marton, Michael Massing, Victor Navasky, Frank del Why I Wasn’t Embedded By Mike Kirsch Olmo, Burl Osborne, Charles A CBS correspondent explains why he chose to go it alone. -

The Definitive Guide to Cybersecurity in Singapore

The Definitive Guide to Cybersecurity in Singapore 4 Things You Need to Know About the New Singapore Cybersecurity Bill Table of Contents Executive Summary 3 History of Cybersecurity Legislation in Singapore 4-6 Need for Legislation 7-8 Objectives of the Omnibus Bill 9 The Key Parts of the Proposed Legislation 10-12 How Resolve Systems Can Help 13 Conclusion 14 About Us and References 15 Glossary Cyber Security Agency of Singapore (CSA) - Formed in April 2015 under the Prime Minister’s Office, it is the national encag y overseeing cybersecurity strategy, operations, education, outreach, and ecosystem development. Critical Information Infrastructures (CII) – A computer or computer system necessary for continuous delivery of essential services which Singapore relies on; the loss or compromise of which will lead to a debilitating impact on national security, defense, foreign relations, economy, public health, public safety, or public order of Singapore. Computer Misuse and Cybersecurity Act (CMCA) - An Act for securing computer material against unauthorized access or modification. Provides authority to measure and ensure cybersecurity. National Cyber Security Center (NCSC) – Monitors and analyzes cyber threat landscape to maintain cyber situational awareness and anticipate future threats. Ministry of Communications and Information (MCI) – Oversees the development of the infocomm media, cybersecurity, and design sectors of Singapore. Who’s Who in Singapore Mr. Lee Hsien Loong - Prime Minister of Singapore Mr. David Koh – Singapore’s Defense Cyber Chief leading Defense Cyber Organization Mr. Teo Chee Hean - Deputy Prime Minister and Coordinating Minister for National Security Dr. Yaacob Ibrahim - Minister for Communications and Information; Minister-in-charge of Cyber Security Executive Summary Singapore is a highly digitized country and is only becoming more so as they expand upon their goal of being a Smart Nation. -

EWISH Vo1ce HERALD

- ,- The 1EWISH Vo1CE HERALD /'f) ,~X{b1)1 {\ ~ SERVING RHODE ISLAND AND SOUTHEASTERN MASSACHUSETTS V C> :,I 18 Nisan 5773 March 29, 2013 Obama gains political capital President asserts that political leaders require a push BY RON KAMPEAS The question now is whether Obama has the means or the WASHINGTON (JTA) - For will to push the Palestinians a trip that U.S. officials had and Israelis back to the nego cautioned was not about get tiating table. ting "deliverables," President U.S. Secretary of State John Obama's apparent success Kerry, who stayed behind during his Middle East trip to follow up with Israeli at getting Israel and Turkey Prime Minister Benjamin to reconcile has raised some Netanyahu's team on what hopes for a breakthrough on happens next, made clear another front: Israeli-Pales tinian negotiations. GAINING I 32 Survivors' testimony Rick Recht 'rocks' in concert. New technology captures memories BY EDMON J. RODMAN In the offices of the Univer Rock star Rick Recht to perform sity of Southern California's LOS ANGELES (JTA) - In a Institute for Creative Technol dark glass building here, Ho ogies, Gutter - who, as a teen in free concert locaust survivor Pinchas Gut ager - had survived Majdanek, ter shows that his memory is Alliance hosts a Jewish rock star'for audiences ofall ages the German Nazi concentra cr ystal clear and his voice is tion camp on the outskirts of BY KARA MARZIALI Recht, who has been compared to James Taylor strong. His responses seem a Lublin, Poland, sounds and [email protected] for his soulfulness and folksy flavor and Bono for bit delayed - not that different looks very much alive. -

Declassified Per E.O. 13526

; THE WHITE HOUSE COUP IBENT L"rL 2287 WASHINGTON MEMORANDUM OF CONVERSATION SUBJECT: Meeting with Prime Minister Khaleda Begum Zia of Bangladesh PARTICIPANTS: The President James A. Baker, Secretary of State Brent Scowcroft, Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs Jonathan T. Howe, Deputy Assistant to the for National Security Affairs James Covey, Acting Assistant Secretary, NEA William B. Milam, U.S. Ambassador to adesh Richard Haass, Senior Director for Near East and South Asian Affairs Mahmud Kibria, Interpreter Khaleda Begum Zia, Prime Minister A.S.M. zur Rahman, Foreign Minister Barrister Nazmul Huda, Information Minister Syed Hasan Ahmed, Principal Secretary to the Prime Minister Ambassador Reaz Rahman, Foreign Secretary Ambassador Abul Ahsan, Bangladesh Ambassador Begum Selina Rahman, Member of Parliament DATE, TIME March 19, 1992, 3:00 - 3:45 p.m. EST AND PLACE: Oval Office Welcome. As you pointed out in our meeting, we have not forgotten that Bangladesh contributed to Desert Storm and fought against aggression. You are not a wealthy country. You took an important step and we are grateful. ~ As for ral ties, they are good. We want them to be better. We recognize your financial problems, as well as your commitment to democracy. We should try to find areas to help. (U) The Prime Minister pointed out to me in our private meeting the textile quota problem and the need to bring more women into the work place. Unfortunately, this is a difficult area for us, but CONFIBE!NTIA:L DECLASSIFIED DECLASSIFY ON: OADR PER E.O. 13526 OtooCJ -06S/ ... 1'11< 1'- 1;;;.,11') J/~ 2 we will look at the possibility of a modest quota increase. -

The War Correspondent

The War Correspondent The War Correspondent Fully updated second edition Greg McLaughlin First published 2002 Fully updated second edition first published 2016 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA www.plutobooks.com Copyright © Greg McLaughlin 2002, 2016 The right of Greg McLaughlin to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7453 3319 9 Hardback ISBN 978 0 7453 3318 2 Paperback ISBN 978 1 7837 1758 3 PDF eBook ISBN 978 1 7837 1760 6 Kindle eBook ISBN 978 1 7837 1759 0 EPUB eBook This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental standards of the country of origin. Typeset by Stanford DTP Services, Northampton, England Simultaneously printed in the European Union and United States of America Contents Acknowledgements ix Abbreviations x 1 Introduction 1 PART I: THE WAR CORRESPONDENT IN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE 2 The War Correspondent: Risk, Motivation and Tradition 9 3 Journalism, Objectivity and War 33 4 From Luckless Tribe to Wireless Tribe: The Impact of Media Technologies on War Reporting 63 PART II: THE WAR CORRESPONDENT AND THE MILITARY 5 Getting to Know Each Other: From Crimea to Vietnam 93 6 Learning and Forgetting: From the Falklands to the Gulf 118 7 Goodbye Vietnam Syndrome: The Embed System in Afghanistan and Iraq 141 PART III: THE WAR CORRESPONDENT AND IDEOLOGICAL FRAMEWORKS 8 Reporting the Cold War and the New World Order 161 9 Reporting the ‘War on Terror’ and the Return of the Evil Empire 190 10 Conclusions: ‘Telling Truth To Power’ – the Ultimate Role of the War Correspondent? 214 1 Introduction William Howard Russell is widely regarded as one of the first war cor- respondents to write for a commercial daily newspaper. -

The Situation of Freedom of Information in Egypt

Reporters Without Borders Contact: Soazig Dollet Head of the Middle East and North Africa Desk Tel: +33 1 4483 8478 Email: [email protected] Contact Geneva: Hélène Sackstein: [email protected] UN Human Rights Council – Universal Periodic Review 20th session - 27 October - 7 November 2014 The situation of freedom of information in Egypt Three years after the “25 January Revolution,” the situation of freedom of information is extremely worrying in Egypt. The different governments since President Hosni Mubarak’s removal have tried to control the media and have not hesitated to adopt repressive measures against journalists. In the past three years, at least nine journalists have been killed in connection with their work, more than 50 have been injured and more than 200 have been arrested. No independent investigation has been carried out to identify and punish those responsible for these abuses. The Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, which governed from February 2011 to June 2012, was open in its attempts to gag the media and used military courts to try journalists and bloggers. After consulting with the SCAF, the information minister announced a temporary freeze on licences for satellite TV stations in September 2011 because of the “need to restore order to increasingly chaotic media scene.” He also threatened other TV stations, accusing them of jeopardizing stability and security. His comments amounted to a declaration of war on the broadcast media and, in particular, independent satellite TV stations that dared to criticize the SCAF’s policies. “Brotherization” of Egypt’s media under Morsi The installation of a Muslim Brotherhood government in the summer of 2012 did not result in any improvement in respect for fundamental freedoms. -

Malda Training Diary

Page 1 of 1 ATI Monograph 13/2006 For restricted circulation only A Probationer’s Training Diary COVER PAGE P. Bhattacharya Learning to Serve Administrative Training Institute Page 2 of 2 Government of West Bengal Page 3 of 3 ATI Monograph 13/2006 For restricted circulation A Probationer’s Training Diary TITLE PAGE P. Bhattacharya Learning to Serve Administrative Training Institute Government of West Bengal Page 4 of 4 Block FC, Bidhannagar (Salt Lake) Kolkata-700106 Page 5 of 5 PREFACE New entrants to the Indian Administrative Service and the West Bengal Civil Service (Executive) have to maintain a Training Diary as part of their district training. While supervising their work in the districts, the ATI faculty has found that in the majority of cases the probationers do not maintain their diaries properly, although these are intended to be records of the details of the training they undergo so that superior officers can check whether they have assimilated the proper lessons from the exposure in the field. During interactions with their Counsellors in the ATI, the trainees have complained that they are handicapped by not having an example to follow. A similar handicap has been reported regarding writing reports of enquiries assigned to probationers in the district. In view of this feedback, the ATI is publishing the diary I maintained in detail as probationer in Malda in 1972, trusting that it will provide civil service probationers with an example of how a training diary can be maintained. We were supposed to send the National Academy of Administration an official training diary and also maintain a personal one. -

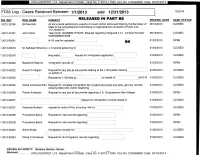

Cases Received Between 1/1/2013 and 12/31/2013 RELEASED IN

UNCLASSIFIED U.S. Department of State Case No. F-2013-17945 Doc No. C05494608 Date: 04/16/2014 FOIA Log - Cases Received Between 1/1/2013 and 12/31/2013 1/2/2014 tEQ REF REQ_NAME SUBJECT RELEASED IN PART B6 RECEIVE DATE CASE STATUS 2012-26796 Bill Marczak All documents pertaining to exports of crowd control items submitted by the Secretary of 08/14/2013 CLOSED State to the Congressional Committees on Appropriations pursuant to Public Law 112-74042512 2012-31657 John Calvit Task Order: SAQMMA11F0233. Request regarding Vanguard 2.2.1. Contract Number: 08/14/2013 CLOSED GS00Q09BGF0048 L-2013-00001 H-1B visa for requester B6 01/02/2013 OPEN 2013-00078 M. Kathleen Minervino J-1 records pertaining to 01/02/2013 CLOSED F-2013-00218 Requestor request for immigration application 01/02/2013 CLOSED F-2013-00220 Bashist M Sharma immigration records of 01/02/2013 OPEN F-2013-00222 Robert D Ahlgren Request for any and all documents relating to the 1-130 petition filed by 01/02/2013 CLOSED on behalf of F-2013-00223 Request for 1-130 filed 1.)- on behalf of NVC # 01/02/2013 CLOSED F-2013-00224 Gloria Contreras Edin Request for complete immigration file including all entries and exits, and any records 01/02/2013 CLOSED showing false USC claims regarding F-2013-00226 Parker Anderson Request for any and all documents regarding U.S. Congressman Sam Steiger. 01/02/2013 OPEN F-2013-00227 request for immigration records receipt # 01/02/2013 CLOSED F-2013-00237 Kayleyne Brottem request for entire A-File, including 1-94 for 01/02/2013 CLOSED F-2013-00238 Providence Spina Request for visa records regarding 01/02/2013 OPEN F-2013-00239 Providence Spina Request for visa records regarding 01/02/2013 OPEN F-2013-00242 Sonia Alcala Immigration records for 01/02/2013 CLOSED F-2013-00243 Gloria C Cardenas Request for all immigration records regarding 01/02/2013 CLOSED REVIEW AUTHORITY: Barbara Nielsen, Senior Reviewer UNCLASSIFIED U.S. -

Report of the Global Inquiry by the International News Safety Institute Into the Protection of Journalists

KILLING THE Messenger REPORT OF THE GLOBAL INQUIRY BY THE INTERNATIONAL NEWS SAFETY INSTITUTE INTO THE PROTECTION OF JOURNALISTS MARCH 2007 KILLING THE Messenger REPORT OF THE GLOBAL INQUIRY BY THE INTERNATIONAL NEWS SAFETY INSTITUTE INTO THE PROTECTION OF JOURNALISTS MARCH 2007 REMIT To prepare a report on the legal, professional and practical issues related to covering the protection of journalists in dangerous situations. The report will consider proposals for reinforcing existing levels of protection including the possible need for a new international convention dealing specifically with the safety and protection of journalists including, if required, an emblem to achieve a secure and safe environment for journalists and those who work with them. Published in Belgium by the International News Safety Institute © 2006 INSI International Press Centre Résidence Palace, Block C 155 rue de la Loi B-1040 Brussels No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of the Editor and publisher. The contents of this book are covered by authors’ rights and the rights to use of contributions rests with the Editor and authors themselves. Designed by Mary Schrider [email protected] Printed by Druk. Hoeilaart, Belgium Contents 1. Foreword ................................................................................................................................2 2. Executive Summary .............................................................................................................6 3. Definitions ...........................................................................................................................15 -

Shoot the Messenger

INSIDE: BEHIND THE MASK OF THE EXECUTIONER G AMERICA’S HOLY WARRIORS G RAPTORS, ROBOTS AND RODS FROM GOD G FOOTBALL & VIOLENCE ThCold e Type READER WRITING WORTH READING G ISSUE 11 G FEBRUARY 2007 SHOOT THE MESSENGER By JESSELYN RADAK DO YOU remember the famous 2001 trophy photo of John Walker Lindh – the American Taliban – the most prominent prisoner of the Afghan war? Although he was seriously wounded, starving, freezing, and exhausted, U.S. soldiers handcuffed him naked, scrawled “shithead” across the blindfold, duct-taped him to a stretcher in an unheated and unlit shipping container, threatened him with death, and posed with him for pictures. Parts of his ordeal were captured on videotape. Sound familiar? – SEE PAGE 22 ThCold e Type READER 3. BEHIND THE MASK OF THE EXECUTIONER By Mara Verheyden-Hilliard 11. EXECUTION IN THE NAME OF FREEDOM By Felicity Arbuthnot 15. AMERICA’S HOLY WARRIORS By Chris Hedges 19. FOOTBALL AND VIOLENCE GO TOGETHER By Robert Fisk ISSUE 11 | FEBUARY 2007 22. COVER STORY – SHOOT THE MESSENGER Editor: By Jesselyn Radack Tony Sutton [email protected] 27. SHOW ME THE INTELLIGENCE For a free subscription By Ray McGovern to the ColdType Reader, email Julia Sutton 31. LOOKING FOR AN EXTREME MAKEOVER at [email protected] By Bill Berkowitz Please type “SUBSCRIBE” in the subject line 34. RAPTORS, ROBOTS AND RODS FROM GOD By Frida Berrigan 41. JOHNNY GOT HIS GUN By William Blum 48. BUSH ANTI-TERROR SUCCESSES ARE ALL FICTION By David Swanson 51. MONEY VERSUS THE MONSOON By Stan Cox 57. KILLING JOURNALISTS IS A WAR CRIME By Amy Goodman 59.