John Bel Edwards Earned a Remarkable Win for Reelection; Here's How He Did It

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix File Anes 1988‐1992 Merged Senate File

Version 03 Codebook ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE ANES 1988‐1992 MERGED SENATE FILE USER NOTE: Much of his file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As a result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. MASTER CODES: The following master codes follow in this order: PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE CAMPAIGN ISSUES MASTER CODES CONGRESSIONAL LEADERSHIP CODE ELECTIVE OFFICE CODE RELIGIOUS PREFERENCE MASTER CODE SENATOR NAMES CODES CAMPAIGN MANAGERS AND POLLSTERS CAMPAIGN CONTENT CODES HOUSE CANDIDATES CANDIDATE CODES >> VII. MASTER CODES ‐ Survey Variables >> VII.A. Party/Candidate ('Likes/Dislikes') ? PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PEOPLE WITHIN PARTY 0001 Johnson 0002 Kennedy, John; JFK 0003 Kennedy, Robert; RFK 0004 Kennedy, Edward; "Ted" 0005 Kennedy, NA which 0006 Truman 0007 Roosevelt; "FDR" 0008 McGovern 0009 Carter 0010 Mondale 0011 McCarthy, Eugene 0012 Humphrey 0013 Muskie 0014 Dukakis, Michael 0015 Wallace 0016 Jackson, Jesse 0017 Clinton, Bill 0031 Eisenhower; Ike 0032 Nixon 0034 Rockefeller 0035 Reagan 0036 Ford 0037 Bush 0038 Connally 0039 Kissinger 0040 McCarthy, Joseph 0041 Buchanan, Pat 0051 Other national party figures (Senators, Congressman, etc.) 0052 Local party figures (city, state, etc.) 0053 Good/Young/Experienced leaders; like whole ticket 0054 Bad/Old/Inexperienced leaders; dislike whole ticket 0055 Reference to vice‐presidential candidate ? Make 0097 Other people within party reasons Card PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PARTY CHARACTERISTICS 0101 Traditional Democratic voter: always been a Democrat; just a Democrat; never been a Republican; just couldn't vote Republican 0102 Traditional Republican voter: always been a Republican; just a Republican; never been a Democrat; just couldn't vote Democratic 0111 Positive, personal, affective terms applied to party‐‐good/nice people; patriotic; etc. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Infonnation Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 KLÀNNISHNESS AND THE KU KLUX KLAN: THE RHETORIC AND ETHICS OF GENRE THEORY DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Brian Robert McGee, B.S., M.S. -

FMOL Letter.6 FMOL Deal Letter

4200 ESSEN LANE 200 HENRY CLAY AVENUE BATON ROUGE, LA 70809 NEW ORLEANS, LA 70118 (225) 922-7447 (504) 899-9511 December 1, 2017 VIA COURIER AND UNITED STATES MAIL The Honorable John Bel Edwards Governor of the State of Louisiana 900 North Third Street, Fourth Floor Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70802 Re: North Louisiana Graduate Medical Education and Health Care Dear Governor Edwards: Please allow this letter to serve as our second and most urgent request to discuss options to collaborate with the State of Louisiana and Louisiana State University regarding graduate medical education and continued care for the uninsured or under-insured in the Shreveport and Monroe areas. We understand the State has granted BRF latitude to pursue options for addressing the problems in Shreveport and Monroe. We respectfully request a meeting as soon as possible to discuss a potential collaboration in greater detail. The importance of keeping and improving graduate medical education in North Louisiana cannot be overstated. Historically, the vast majority of new doctors tend to remain in the geographical area where they were trained. With the shortage of physicians in Louisiana, it is imperative to keep our teaching facilities open and thriving. Similarly, the care provided to the most needy of the State must be preserved. University Health has historically served the Medicaid and indigent population. Preserving and enhancing their access to care is not only required under the Louisiana constitution, but critical to the long term development of growth of our State. While other providers may have historically been unwilling to partner with LSU and the State to support graduate medical education and care for the Medicaid and indigent population, LCMC and FMOLHS chose to support the State’s goals to create successful partnerships in New Orleans and Baton Rouge. -

Congressional Record—Senate S7020

S7020 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE December 9, 2016 While BARBARA’s departure leaves diction, helping Congress to pass the term limit pledge he had made to his the Senate without one of its strongest Comprehensive Addiction and Recov- Hoosier constituents and did not run champions for the environment, col- ery Act, CARA, to improve prevention for reelection to the Senate. lege affordability, and reproductive and treatment, support those in recov- For many people, 18 years in Con- rights, we will continue to fight for ery, and ensure first responders have gress might be enough, but Senator these core priorities as she would have the tools they need. She helped to pass COATS was just getting started. After done. legislation to reauthorize the Violence he left the Senate, he joined the pres- It has been a privilege to serve along- Against Women Act, crack down on tigious law firm of Verner, Liipfert, side a steadfast champion like BAR- sexual assault in the military, make Bernhard, McPherson and Hand. In BARA. college campuses safer, and improve 2001, then-President Bush nominated She has served Maryland with utter mental health first aid training and Senator COATS to be Ambassador to the conviction, and I know she will con- suicide prevention programs. Federal Republic of Germany. He ar- tinue to be a progressive force in this Senator AYOTTE has followed in the rived in Germany just 3 days before the new chapter of her life. footsteps of other Republican Senators September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. Aloha, BARBARA, and a hui hou, from New England, such as Robert In the aftermath of 9/11, Ambassador ‘‘until we meet again.’’ Stafford of Vermont and John Chafee Coats established excellent relations f of Rhode Island, who are true conserv- with then-opposition leader and future TRIBUTES TO DEPARTING atives when it comes to the environ- German Chancellor Angela Merkel—a SENATORS ment. -

Southern University and A&M College Commencement Program

Southern University and A&M College Commencement SPRING 2020 SUMMER 2020 AUGUST 7, 2020 B A T O N R O U G E , L O U I S I A N A Southern University and A&M College B A T O N R O U G E, L O U I S I A N A Spring & Summer Commencement August 7, 2020 Southern University and A & M C ollege History he movement in Louisiana for an equal opportunity institution of higher learning was sponsored in the 1879 Louisiana State Constitutional Convention by delegates P.B.S. Pinchback, T.T. Allain, T.B. Stamps, and Henry Demas. TTheir efforts resulted in the establishment of this institution for the education of persons of color in New Orleans. Southern University, chartered by Legislative Act 87 in April 1880, had a 12-member Board of Trustees. The act provided for the establishment of a faculty of “arts and letters” competent in “every branch of liberal education.” The charter sought to open doors of state higher education to all “persons competent and deserving.” Southern opened with 12 students and a $10,000 appropriation. With the passage of the 1890 Morrill Act, the University was reorganized to receive land-grant funds. In 1912, Legislative Act 118 authorized the closing of Southern University in New Orleans, the sale of its property, and the reestablishment of the University on a new site. In 1914, the “new” Southern University opened in Scotlandville, Louisiana, receiving a portion of a $50,000 national land-grant appropriation. Southern University in New Orleans and Southern University in Shreveport were authorized by Legislative Acts 28 and 42 in 1956 and 1964 respectively. -

A FAILURE of INITIATIVE Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina

A FAILURE OF INITIATIVE Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina U.S. House of Representatives 4 A FAILURE OF INITIATIVE A FAILURE OF INITIATIVE Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina Union Calendar No. 00 109th Congress Report 2nd Session 000-000 A FAILURE OF INITIATIVE Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina Report by the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpoacess.gov/congress/index.html February 15, 2006. — Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U. S. GOVERNMEN T PRINTING OFFICE Keeping America Informed I www.gpo.gov WASHINGTON 2 0 0 6 23950 PDF For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-0001 COVER PHOTO: FEMA, BACKGROUND PHOTO: NASA SELECT BIPARTISAN COMMITTEE TO INVESTIGATE THE PREPARATION FOR AND RESPONSE TO HURRICANE KATRINA TOM DAVIS, (VA) Chairman HAROLD ROGERS (KY) CHRISTOPHER SHAYS (CT) HENRY BONILLA (TX) STEVE BUYER (IN) SUE MYRICK (NC) MAC THORNBERRY (TX) KAY GRANGER (TX) CHARLES W. “CHIP” PICKERING (MS) BILL SHUSTER (PA) JEFF MILLER (FL) Members who participated at the invitation of the Select Committee CHARLIE MELANCON (LA) GENE TAYLOR (MS) WILLIAM J. -

Understanding the 2016 Gubernatorial Elections by Jennifer M

GOVERNORS The National Mood and the Seats in Play: Understanding the 2016 Gubernatorial Elections By Jennifer M. Jensen and Thad Beyle With a national anti-establishment mood and 12 gubernatorial elections—eight in states with a Democrat as sitting governor—the Republicans were optimistic that they would strengthen their hand as they headed into the November elections. Republicans already held 31 governor- ships to the Democrats’ 18—Alaska Gov. Bill Walker is an Independent—and with about half the gubernatorial elections considered competitive, Republicans had the potential to increase their control to 36 governors’ mansions. For their part, Democrats had a realistic chance to convert only a couple of Republican governorships to their party. Given the party’s win-loss potential, Republicans were optimistic, in a good position. The Safe Races North Dakota Races in Delaware, North Dakota, Oregon, Utah Republican incumbent Jack Dalrymple announced and Washington were widely considered safe for he would not run for another term as governor, the incumbent party. opening the seat up for a competitive Republican primary. North Dakota Attorney General Wayne Delaware Stenehjem received his party’s endorsement at Popular Democratic incumbent Jack Markell was the Republican Party convention, but multimil- term-limited after fulfilling his second term in office. lionaire Doug Burgum challenged Stenehjem in Former Delaware Attorney General Beau Biden, the primary despite losing the party endorsement. eldest son of former Vice President Joe Biden, was Lifelong North Dakota resident Burgum had once considered a shoo-in to succeed Markell before founded a software company, Great Plains Soft- a 2014 recurrence of brain cancer led him to stay ware, that was eventually purchased by Microsoft out of the race. -

Ronald Reagan, Louisiana, and the 1980 Presidential Election Matthew Ad Vid Caillet Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2011 "Are you better off "; Ronald Reagan, Louisiana, and the 1980 Presidential election Matthew aD vid Caillet Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Caillet, Matthew David, ""Are you better off"; Ronald Reagan, Louisiana, and the 1980 Presidential election" (2011). LSU Master's Theses. 2956. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2956 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ―ARE YOU BETTER OFF‖; RONALD REAGAN, LOUISIANA, AND THE 1980 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History By Matthew David Caillet B.A. and B.S., Louisiana State University, 2009 May 2011 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to many people for the completion of this thesis. Particularly, I cannot express how thankful I am for the guidance and assistance I received from my major professor, Dr. David Culbert, in researching, drafting, and editing my thesis. I would also like to thank Dr. Wayne Parent and Dr. Alecia Long for having agreed to serve on my thesis committee and for their suggestions and input, as well. -

The Gubernatorial Elections of 2015: Hard-Fought Races for the Open Seats by Jennifer M

GOVERNORS The Gubernatorial Elections of 2015: Hard-Fought Races for the Open Seats By Jennifer M. Jensen and Thad Beyle Only three governors were elected in 2015. Kentucky, Louisiana and Mississippi are the only states that hold their gubernatorial elections during the year prior to the presidential election. This means that these three states can be early indicators of any voter unrest that might unleash itself more broadly in the next year’s congressional and presidential elections, and we saw some of this in the two races where candidates were vying for open seats. Mississippi Gov. Phil Bryant (R) was elected to a second term, running in a state that strongly favored his political party. Both Kentucky and Louisiana have elected Democrats and Republicans to the governorship in recent years, and each race was seen as up for grabs by many political pundits. In the end, each election resulted in the governorship turning over to the other political party. Though Tea Party sentiments played a signifi- he lost badly to McConnell, he had name recog- cant role in the primary elections in Kentucky and nition when he entered the gubernatorial race as Louisiana, none of the general elections reflected an anti-establishment candidate who ran an out- the vigor that the Tea Party displayed in the 2014 sider’s campaign against two Republicans who had gubernatorial elections. With only two open races held elected office. Bevin funded the vast majority and one safe incumbent on the ballot, the 2015 of his primary spending himself, contributing more elections were generally not characterized as a than $2.4 million to his own campaign. -

'Voting Rights Act Made Things Happen'

www.mississippilink.com Vol. 21, No. 52 october 22- 28, 2015 50¢ October is Hispanic Heritage Month ‘Voting Rights Act Latinfest becomes made things happen’ largest Latino Mississippi Department of Archives and History joins Center of Southern Culture in historic festival in Mississippi film/discussion of 50-year-old Voting Rights Act By Janice K. Neal-Vincent, Ph.D. Contributing Writer The Voting Rights Act of 1965 was signed into law by President Lyn- don Johnson on August 6, 1965. It purported to overcome legal barriers at the state and local lev- Civil rights veteran els that prevented African Robert Clark Americans from exer- cising their right to vote huge crowd. under the 15th Amendment McLemore re- (1870) to the Constitution of vealed that he the United States. grew up in De A filmed Southern Docu- Soto County and mentary Project was shown that Sam Williams and discussed recently at the was the first black Mississippi Department of voter in that par- Archives and History. MDAH ticular county. He commended Wil- Israel Martinez (at podium), Latin American Business Association, is joined by JCVB representatives partnered with the Center of Jennifer Byrd, Cherry Ratliff, Jennifer Chance, Rickey Thigpen, Mary Current, and (seated) Jay Southern Culture in Film at liams, Medgar The Voting Rights Act film Huffstatler, of the American Red Cross. the University of Mississippi. Wiley Evers, who Director and producer was the first per- fought the oppressive regime. By Ayesha K. Mustafaa panic population reaching without ever leaving the Andy Harper (Instructional manent field secretary for the And because of their efforts, Editor over 81,000, Latinfest orga- state of Mississippi. -

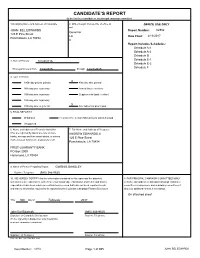

Candidate's Report

CANDIDATE’S REPORT (to be filed by a candidate or his principal campaign committee) 1.Qualifying Name and Address of Candidate 2. Office Sought (Include title of office as OFFICE USE ONLY well JOHN BEL EDWARDS Report Number: 62862 Governor 125 E Pine Street LA Date Filed: 2/13/2017 Ponchatoula, LA 70454 0 Report Includes Schedules: Schedule A-1 Schedule A-2 Schedule B Schedule E-1 3. Date of Primary 10/24/2015 Schedule E-2 Schedule F This report covers from 11/2/2015 through 12/21/2015 4. Type of Report: X 180th day prior to primary 40th day after general 90th day prior to primary Annual (future election) 30th day prior to primary Supplemental (past election) 10th day prior to primary X 10th day prior to general Amendment to prior report 5. FINAL REPORT if: Withdrawn Filed after the election AND all loans and debts paid Unopposed 6. Name and Address of Financial Institution 7. Full Name and Address of Treasurer (You are required by law to use one or more ANDREW EDWARDS, II banks, savings and loan associations, or money 125 E Pine Street market mutual fund as the depository of all Ponchatoula, LA 70454 FIRST GUARANTY BANK PO Box 2009 Hammond, LA 70404 9. Name of Person Preparing Report GWEN B BARSLEY Daytime Telephone (985) 386-9525 10. WE HEREBY CERTIFY that the information contained in this report and the attached 8. FOR PRINCIPAL CAMPAIGN COMMITTEES ONLY schedules is true and correct to the best of our knowledge, information and belief, and that no a. -

Johnston (J. Bennett) Papers

Johnston (J. Bennett) Papers Mss. #4473 Inventory Compiled by Emily Robison & Wendy Rogers Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections Special Collections, Hill Memorial Library Louisiana State University Libraries Baton Rouge, Louisiana Spring 2002 J. Bennett Johnston Papers Mss. 4473 1957-1997 LSU Libraries Special Collections Contents of Inventory Summary 3 Biographical/Historical Note 4 Scope and Content Note 5 Series, Sub-Series Description 6 Index Terms 16 Container List 19 Appendices 20 Use of manuscript materials. If you wish to examine items in the manuscript group, please fill out a call slip specifying the materials you wish to see. Consult the container list for location information needed on the call slip. Photocopying. Should you wish to request photocopies, please consult a staff member before segregating the items to be copied. The existing order and arrangement of unbound materials must be maintained. Publication. Readers assume full responsibility for compliance with laws regarding copyright, literary property rights, and libel. Permission to examine archival and manuscript materials does not constitute permission to publish. Any publication of such materials beyond the limits of fair use requires specific prior written permission. Requests for permission to publish should be addressed in writing to the Head of Public Services, Special Collections, LSU Libraries, Baton Rouge, LA, 70803-3300. When permission to publish is granted, two copies of the publication will be requested for the LLMVC. Proper acknowledgment of LLMVC materials must be made in any resulting writing or publications. The correct form of citation for this manuscript group is given on the summary page. Copies of scholarly publications based on research in the Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections are welcomed.