Un Ballo in Maschera

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Translation of the German by Tom Hammond

Richard Strauss Susan Bullock Sally Burgess John Graham-Hall John Wegner Philharmonia Orchestra Sir Charles Mackerras CHAN 3157(2) (1864 –1949) © Lebrecht Music & Arts Library Photo Music © Lebrecht Richard Strauss Salome Opera in one act Libretto by the composer after Hedwig Lachmann’s German translation of Oscar Wilde’s play of the same name, English translation of the German by Tom Hammond Richard Strauss 3 Herod Antipas, Tetrarch of Judea John Graham-Hall tenor COMPACT DISC ONE Time Page Herodias, his wife Sally Burgess mezzo-soprano Salome, Herod’s stepdaughter Susan Bullock soprano Scene One Jokanaan (John the Baptist) John Wegner baritone 1 ‘How fair the royal Princess Salome looks tonight’ 2:43 [p. 94] Narraboth, Captain of the Guard Andrew Rees tenor Narraboth, Page, First Soldier, Second Soldier Herodias’s page Rebecca de Pont Davies mezzo-soprano 2 ‘After me shall come another’ 2:41 [p. 95] Jokanaan, Second Soldier, First Soldier, Cappadocian, Narraboth, Page First Jew Anton Rich tenor Second Jew Wynne Evans tenor Scene Two Third Jew Colin Judson tenor 3 ‘I will not stay there. I cannot stay there’ 2:09 [p. 96] Fourth Jew Alasdair Elliott tenor Salome, Page, Jokanaan Fifth Jew Jeremy White bass 4 ‘Who spoke then, who was that calling out?’ 3:51 [p. 96] First Nazarene Michael Druiett bass Salome, Second Soldier, Narraboth, Slave, First Soldier, Jokanaan, Page Second Nazarene Robert Parry tenor 5 ‘You will do this for me, Narraboth’ 3:21 [p. 98] First Soldier Graeme Broadbent bass Salome, Narraboth Second Soldier Alan Ewing bass Cappadocian Roger Begley bass Scene Three Slave Gerald Strainer tenor 6 ‘Where is he, he, whose sins are now without number?’ 5:07 [p. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 118, 1998-1999

BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA 1 I O Z AWA ' T W E N T Y- F I F 1 H ANNIVERSARY SEASO N 1 1 8th Season • 1 998-99 Bring your Steinway: < With floor plans from acre gated community atop 2,100 to 5,000 square feet, prestigious Fisher Hill you can bring your Concert Jointly marketed by Sotheby's Grand to Longyear. International Realty and You'll be enjoying full-service, Hammond Residential Real Estate. single-floor condominium living at Priced from $1,100,000. its absolutefinest, all harmoniously Call Hammond Real Estate at located on an extraordinary eight- (617) 731-4644, ext. 410. LONGYEAR at Jisner Jiill BROOKLINE Seiji Ozawa, Music Director 25TH ANNIVERSARY SEASON Bernard Haitink, Principal Guest Conductor One Hundred and Eighteenth Season, 1998-99 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. R. Willis Leith, Jr., Chairman Nicholas T. Zervas, President Peter A. Brooke, Vice-Chairman William J. Poorvu, Vice-Chairman and Treasurer Harvey Chet Krentzman, Vice-Chairman Ray Stata, Vice-Chairman Harlan E. Anderson Deborah B. Davis Edna S. Kalman Vincent M. O'Reilly Gabriella Beranek Nina L. Doggett George Krupp Peter C. Read James E Cleary Nancy J. Fitzpatrick Mrs. August R. Meyer Hannah H. Schneider John F. Cogan, Jr. Charles K. Gifford, Richard P. Morse Thomas G. Sternberg Julian Cohen ex-ojficio Mrs. Robert B. Stephen R. Weiner William F. Connell Avram J. Goldberg Newman Margaret Williams- William M. Crozier, Jr. Thelma E. Goldberg Robert P. O'Block, DeCelles, ex-qfficio Nader F Darehshori Julian T. Houston ex-ojficio Life Trustees Vernon R. -

Donizetti Operas and Revisions

GAETANO DONIZETTI LIST OF OPERAS AND REVISIONS • Il Pigmalione (1816), libretto adapted from A. S. Sografi First performed: Believed not to have been performed until October 13, 1960 at Teatro Donizetti, Bergamo. • L'ira d'Achille (1817), scenes from a libretto, possibly by Romani, originally done for an opera by Nicolini. First performed: Possibly at Bologna where he was studying. First modern performance in Bergamo, 1998. • Enrico di Borgogna (1818), libretto by Bartolomeo Merelli First performed: November 14, 1818 at Teatro San Luca, Venice. • Una follia (1818), libretto by Bartolomeo Merelli First performed: December 15, 1818 at Teatro San Luca,Venice. • Le nozze in villa (1819), libretto by Bartolomeo Merelli First performed: During Carnival 1820-21 at Teatro Vecchio, Mantua. • Il falegname di Livonia (also known as Pietro, il grande, tsar delle Russie) (1819), libretto by Gherardo Bevilacqua-Aldobrandini First performed: December 26, 1819 at the Teatro San Samuele, Venice. • Zoraida di Granata (1822), libretto by Bartolomeo Merelli First performed: January 28, 1822 at the Teatro Argentina, Rome. • La zingara (1822), libretto by Andrea Tottola First performed: May 12, 1822 at the Teatro Nuovo, Naples. • La lettera anonima (1822), libretto by Giulio Genoino First performed: June 29, 1822 at the Teatro del Fondo, Naples. • Chiara e Serafina (also known as I pirati) (1822), libretto by Felice Romani First performed: October 26, 1822 at La Scala, Milan. • Alfredo il grande (1823), libretto by Andrea Tottola First performed: July 2, 1823 at the Teatro San Carlo, Naples. • Il fortunate inganno (1823), libretto by Andrea Tottola First performed: September 3, 1823 at the Teatro Nuovo, Naples. -

MICHAEL FINNISSY at 70 the PIANO MUSIC (9) IAN PACE – Piano Recital at Deptford Town Hall, Goldsmith’S College, London

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. (2016). Michael Finnissy at 70: The piano music (9). This is the other version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/17520/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] MICHAEL FINNISSY AT 70 THE PIANO MUSIC (9) IAN PACE – Piano Recital at Deptford Town Hall, Goldsmith’s College, London Thursday December 1st, 2016, 6:00 pm The event will begin with a discussion between Michael Finnissy and Ian Pace on the Verdi Transcriptions. MICHAEL FINNISSY Verdi Transcriptions Books 1-4 (1972-2005) 6:15 pm Books 1 and 2: Book 1 I. Aria: ‘Sciagurata! a questo lido ricercai l’amante infido!’, Oberto (Act 2) II. Trio: ‘Bella speranza in vero’, Un giorno di regno (Act 1) III. Chorus: ‘Il maledetto non ha fratelli’, Nabucco (Part 2) IV. -

Carmen: the Complete Opera Free

FREE CARMEN: THE COMPLETE OPERA PDF Georges Bizet,Clinical Professor at the College of Medicine William Berger MD,David Foil | 144 pages | 15 Dec 2005 | Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers Inc | 9781579125080 | English | New York, United States Complete Opera (Carmen) by G. Bizet - free download on MusicaNeo Sheet music file Free. Sheet music file 4. Sheet music file 1. Sheet music file Sheet music file including a license for an unlimited number of performances, limited to one year. Read license 1. Sheet music file 7. Upload Sheet Music. Publish Sheet Music. En De Ru Pt. Georges Bizet. Piano score. Look inside. Sheet music file Free Uploader Library. PDF, Arrangement for piano solo of the opera "Carmen" written by Bizet. If you have any question don't hesitate to contact us at olcbarcelonamusic gmail. Act I. Act II. Act III. Act IV. PDF, 8. Act II No. Act III No. PDF, 9. Act IV No. PDF, 5. Act I, Piano-vocal score. Act II, Piano-vocal score. Act III, Piano-vocal score. Piano-vocal score. Act IV, Piano-vocal score. Overture and Act I. PDF, 2. Overture, for sextet, Op. PDF, 1. Overture, for piano four hands. Overture, for piano. Entr'acte to Act IV, for string quartet. Orchestral harp part. Orchestral Harp. Orchestral cello part. PDF, 4. Orchestral part of Celli. Orchestral contrabasses part. Orchestral part of Contrabasses. Orchestral violin I part. Orchestral Violin I. Orchestral violin II part. Orchestral parts of Violini Carmen: The Complete Opera. Orchestral viola part. Carmen: The Complete Opera part of Viola. Orchestral clarinet I part. -

Press Information Eno 2013/14 Season

PRESS INFORMATION ENO 2013/14 SEASON 1 #ENGLISHENO1314 NATIONAL OPERA Press Information 2013/4 CONTENTS Autumn 2013 4 FIDELIO Beethoven 6 DIE FLEDERMAUS Strauss 8 MADAM BUtteRFLY Puccini 10 THE MAGIC FLUte Mozart 12 SATYAGRAHA Glass Spring 2014 14 PeteR GRIMES Britten 18 RIGOLetto Verdi 20 RoDELINDA Handel 22 POWDER HeR FAce Adès Summer 2014 24 THEBANS Anderson 26 COSI FAN TUtte Mozart 28 BenvenUTO CELLINI Berlioz 30 THE PEARL FISHERS Bizet 32 RIveR OF FUNDAMent Barney & Bepler ENGLISH NATIONAL OPERA Press Information 2013/4 3 FIDELIO NEW PRODUCTION BEETHoven (1770–1827) Opens: 25 September 2013 (7 performances) One of the most sought-after opera and theatre directors of his generation, Calixto Bieito returns to ENO to direct a new production of Beethoven’s only opera, Fidelio. Bieito’s continued association with the company shows ENO’s commitment to highly theatrical and new interpretations of core repertoire. Following the success of his Carmen at ENO in 2012, described by The Guardian as ‘a cogent, gripping piece of work’, Bieito’s production of Fidelio comes to the London Coliseum after its 2010 premiere in Munich. Working with designer Rebecca Ringst, Bieito presents a vast Escher-like labyrinth set, symbolising the powerfully claustrophobic nature of the opera. Edward Gardner, ENO’s highly acclaimed Music Director, 2013 Olivier Award-nominee and recipient of an OBE for services to music, conducts an outstanding cast led by Stuart Skelton singing Florestan and Emma Bell as Leonore. Since his definitive performance of Peter Grimes at ENO, Skelton is now recognised as one of the finest heldentenors of his generation, appearing at the world’s major opera houses, including the Metropolitan Opera, New York, and Opéra National de Paris. -

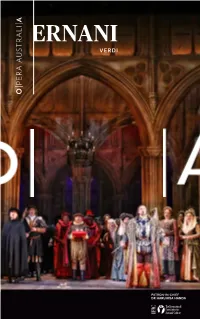

Ernani Program

VERDI PATRON-IN-CHIEF DR HARUHISA HANDA Celebrating the return of World Class Opera HSBC, as proud partner of Opera Australia, supports the many returns of 2021. Together we thrive Issued by HSBC Bank Australia Limited ABN 48 006 434 162 AFSL No. 232595. Ernani Composer Ernani State Theatre, Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) Diego Torre Arts Centre Melbourne Librettist Don Carlo, King of Spain Performance dates Francesco Maria Piave Vladimir Stoyanov 13, 15, 18, 22 May 2021 (1810-1876) Don Ruy Gomez de Silva Alexander Vinogradov Running time: approximately 2 hours and 30 Conductor Elvira minutes, including one interval. Carlo Montanaro Natalie Aroyan Director Giovanna Co-production by Teatro alla Scala Sven-Eric Bechtolf Jennifer Black and Opera Australia Rehearsal Director Don Riccardo Liesel Badorrek Simon Kim Scenic Designer Jago Thank you to our Donors Julian Crouch Luke Gabbedy Natalie Aroyan is supported by Costume Designer Roy and Gay Woodward Kevin Pollard Opera Australia Chorus Lighting Designer Chorus Master Diego Torre is supported by Marco Filibeck Paul Fitzsimon Christine Yip and Paul Brady Video Designer Assistant Chorus Master Paul Fitzsimon is supported by Filippo Marta Michael Curtain Ina Bornkessel-Schlesewsky and Matthias Schlesewsky Opera Australia Actors The costumes for the role of Ernani in this production have been Orchestra Victoria supported by the Concertmaster Mostyn Family Foundation Sulki Yu You are welcome to take photos of yourself in the theatre at interval, but you may not photograph, film or record the performance. -

KING FM SEATTLE OPERA CHANNEL Featured Full-Length Operas

KING FM SEATTLE OPERA CHANNEL Featured Full-Length Operas GEORGES BIZET EMI 63633 Carmen Maria Stuarda Paris Opera National Theatre Orchestra; René Bologna Community Theater Orchestra and Duclos Chorus; Jean Pesneaud Childrens Chorus Chorus Georges Prêtre, conductor Richard Bonynge, conductor Maria Callas as Carmen (soprano) Joan Sutherland as Maria Stuarda (soprano) Nicolai Gedda as Don José (tenor) Luciano Pavarotti as Roberto the Earl of Andréa Guiot as Micaëla (soprano) Leicester (tenor) Robert Massard as Escamillo (baritone) Roger Soyer as Giorgio Tolbot (bass) James Morris as Guglielmo Cecil (baritone) EMI 54368 Margreta Elkins as Anna Kennedy (mezzo- GAETANO DONIZETTI soprano) Huguette Tourangeau as Queen Elizabeth Anna Bolena (soprano) London Symphony Orchestra; John Alldis Choir Julius Rudel, conductor DECCA 425 410 Beverly Sills as Anne Boleyn (soprano) Roberto Devereux Paul Plishka as Henry VIII (bass) Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and Ambrosian Shirley Verrett as Jane Seymour (mezzo- Opera Chorus soprano) Charles Mackerras, conductor Robert Lloyd as Lord Rochefort (bass) Beverly Sills as Queen Elizabeth (soprano) Stuart Burrows as Lord Percy (tenor) Robert Ilosfalvy as roberto Devereux, the Earl of Patricia Kern as Smeaton (contralto) Essex (tenor) Robert Tear as Harvey (tenor) Peter Glossop as the Duke of Nottingham BRILLIANT 93924 (baritone) Beverly Wolff as Sara, the Duchess of Lucia di Lammermoor Nottingham (mezzo-soprano) RIAS Symphony Orchestra and Chorus of La Scala Theater Milan DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 465 964 Herbert von -

25 Recommended Recordings of Negro

25 Recommended Recordings of Negro Spirituals for Solo Vocalist Compiled by Randye Jones This is a sample of recordings recommended for enhancing library collections of Spirituals and, thus, is limited (with one exception) to recordings available on compact disc. This list includes a variety of voice types, time periods, interpretative styles, and accompaniment. Selections were compiled from The Spirituals Database, a resource referencing more than 450 recordings of Negro Spiritual art songs. Marian Anderson, Contralto He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands (1994) RCA Victor 09026-61960-2 CD, with piano Songs by Hall Johnson, Harry T. Burleigh, Lawrence Brown, J. Rosamond Johnson, Hamilton Forrest, Florence Price, Edward Boatner, Roland Hayes Spirituals (1999) RCA Victor Red Seal 09026-63306-2 CD, recorded between 1936 and 1952, with piano Songs by Hall Johnson, John C. Payne, Harry T. Burleigh, Lawrence Brown, Hamilton Forrest, Robert MacGimsey, Roland Hayes, Florence Price, Edward Boatner, R. Nathaniel Dett Angela Brown, Soprano Mosiac: a collection of African-American spirituals with piano and guitar (2004) Albany Records TROY721 CD, variously with piano, guitar Songs by Angela Brown, Undine Smith Moore, Moses Hogan, Evelyn Simpson- Curenton, Margaret Bonds, Florence Price, Betty Jackson King, Roland Hayes, Joseph Joubert Todd Duncan, Baritone Negro Spirituals (1952) Allegro ALG3022 LP, with piano Songs by J. Rosamond Johnson, Harry T. Burleigh, Lawrence Brown, William C. Hellman, Edward Boatner Denyce Graves, Mezzo-soprano Angels Watching Over Me (1997) NPR Classics CD 0006 CD, variously with piano, chorus, a cappella Songs by Hall Johnson, Harry T. Burleigh, Marvin Mills, Evelyn Simpson- Curenton, Shelton Becton, Roland Hayes, Robert MacGimsey Roland Hayes, Tenor Favorite Spirituals (1995) Vanguard Classics OVC 6022 CD, with piano Songs by Roland Hayes Barbara Hendricks, Soprano Give Me Jesus (1998) EMI Classics 7243 5 56788 2 9 CD, variously with chorus, a cappella Songs by Moses Hogan, Roland Hayes, Edward Boatner, Harry T. -

Verdian Musicodramatic Expression in Un Ballo in Maschera

VERDIAN MUSICODRAMATIC EXPRESSION IN UN BALLO IN MASCHERA A RESEARCH PAPER SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTERS OF MUSIC BY JERRY POLMAN DR. CRAIG PRIEBE – ADVISER BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA JULY 2010 | 1 On September 19, 1857, Giuseppe Verdi wrote to the impresario at San Carlo that he was “in despair.” He was commissioned to write an opera for the 1858 carnival season but could not find what he deemed a suitable libretto. For many years he desired to compose an opera based on Shakespeare‟s King Lear but he deemed the singers in Naples to be inadequate for the task. Nevertheless, he writes in the same letter that he is now “…condensing a French drama, Gustave III di Svezia, libretto by Scribe, given at the [Paris Grand Opéra with music by Auber] about twenty years ago [1833]. It is grand and vast; it is beautiful; but this too has the conventional forms of all works for music, something which I have never liked and I now find unbearable. I repeat, I am in despair, because it is too late to find other subjects.”1 Despite finding it “unbearable” Verdi continued to work on Gustave, calling on the talents of Antonia Somma to write the libretto. However, Verdi did not foresee the intense scrutiny that would be leveled against it. Upon receiving word from Vincenzo Torelli (the impresario of the San Carlo Opera House), that nothing less than a new production would suffice to fulfill his contract, Verdi and Somma set to work immediately on Gustave. -

Così Fan Tutte Cast Biography

Così fan tutte Cast Biography (Cahir, Ireland) Jennifer Davis is an alumna of the Jette Parker Young Artist Programme and has appeared at the Royal Opera, Covent Garden as Adina in L’Elisir d’Amore; Erste Dame in Die Zauberflöte; Ifigenia in Oreste; Arbate in Mitridate, re di Ponto; and Ines in Il Trovatore, among other roles. Following her sensational 2018 role debut as Elsa von Brabant in a new production of Lohengrin conducted by Andris Nelsons at the Royal Opera House, Davis has been propelled to international attention, winning praise for her gleaming, silvery tone, and dramatic characterisation of remarkable immediacy. (Sacramento, California) American Mezzo-soprano Irene Roberts continues to enjoy international acclaim as a singer of exceptional versatility and vocal suppleness. Following her “stunning and dramatically compelling” (SF Classical Voice) performances as Carmen at the San Francisco Opera in June, Roberts begins the 2016/2017 season in San Francisco as Bao Chai in the world premiere of Bright Sheng’s Dream of the Red Chamber. Currently in her second season with the Deutsche Oper Berlin, her upcoming assignments include four role debuts, beginning in November with her debut as Urbain in David Alden’s new production of Les Huguenots led by Michele Mariotti. She performs in her first Ring cycle in 2017 singing Waltraute in Die Walküre and the Second Norn in Götterdämmerung under the baton of Music Director Donald Runnicles, who also conducts her role debut as Hänsel in Hänsel und Gretel. Additional roles for Roberts this season include Rosina in Il barbiere di Siviglia, Fenena in Nabucco, Siebel in Faust, and the title role of Carmen at Deutsche Oper Berlin. -

Le Cheval De Bronze De Daniel Auber

GALERÍA DE RAREZAS Le cheval de bronze de Daniel Auber por Ricardo Marcos oy exploraremos una sala encantadora, generosamente iluminada, con grandes mesas en donde podemos degustar algunos de los chocolates franceses más sofisticados y deliciosos, de esta galería de rarezas operísticas. El compositor en cuestión gozó de la gloria operística y fue el segundo director en la historia del Conservatorio de París. Su Hmusa es ligera e irresistible, si bien una de sus grandes creaciones es una obra dramática. Durante la década de 1820 París se convirtió en el centro del mundo musical gracias en gran medida a tres casas de ópera emblemáticas; La Opéra de Paris, la Opéra Comique y el Thêatre Italien. Daniel Auber, quien había estudiado con Luigi Cherubini, se convirtió en el gran señor de la ópera cómica y habría de ser modelo para compositores como Adolphe Adam, Francois Bazin y Victor Masse, entre otros. Dotado desde pequeño para la música, Auber había aprendido a tocar violín y el piano pero fue hasta 1811 en que perfeccionó sus estudios musicales y se dedicó de tiempo completo a la composición. Entre sus mejores obras dentro del campo de la ópera cómica se encuentran joyas como Fra Diavolo y Le domino noir; sin embargo, hay una obra más para completar un trío de obras maestras que, junto con las grandes óperas La muette de Portici, Haydée y Gustave III, conforman lo mejor de su producción. Estrenada el 23 de marzo de 1835, con un libreto de Eugène Scribe, el sempiterno libretista francés de la primera mitad del siglo XIX, El caballo de bronce es una obra deliciosa por la vitalidad de sus duetos, ensambles y la gracia de sus arias, muchas de ellas demandantes; con dos roles brillantes para soprano, uno para tenor, uno para barítono y uno para bajo.