2012 Herb of the Year

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redalyc.Comparative Evaluation of Dietary Oregano, Anise and Olive

Revista Brasileira de Ciência Avícola ISSN: 1516-635X [email protected] Fundação APINCO de Ciência e Tecnologia Avícolas Brasil Christaki, EV; Bonos, EM; Florou-Paneri, PC Comparative evaluation of dietary oregano, anise and olive leaves in laying Japanese quails Revista Brasileira de Ciência Avícola, vol. 13, núm. 2, abril-junio, 2011, pp. 97-101 Fundação APINCO de Ciência e Tecnologia Avícolas Campinas, SP, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=179719101003 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Brazilian Journal of Poultry Science Revista Brasileira de Ciência Avícola Comparative Evaluation of Dietary Oregano, Anise ISSN 1516-635X Apr - Jun 2011 / v.13 / n.2 / 97-101 and Olive Leaves in Laying Japanese Quails nAuthor(s) ABSTRACT Christaki EV Bonos EM Aim of the present study was the comparative evaluation of the Florou-Paneri PC effect of ground oregano, anise and olive leaves as feed additives on Laboratory of Nutrition performance and some egg quality characteristics of laying Japanese Faculty of Veterinary Medicine quails. A total of 189 Coturnix japonica quails (126 females and 63 Aristotle University of Thessaloniki Thessaloniki, Greece males), 149 days old, were randomly allocated into seven equal groups with three subgroups of 9 birds each (6 females and 3 males). A commercial laying diet was fed to the control group. The remaining six groups were fed the same diet supplemented with oregano at 10 g/kg or 20 g/kg, anise at 10 g/kg or 20 g/kg and olive leaves at 10 g/ kg or at 20 g/kg. -

Mint in the Garden Kristie Buckland and Dan Drost Vegetable Specialist

Revised May 2020 Mint in the Garden Kristie Buckland and Dan Drost Vegetable Specialist Summary Plants: Mint can be grown from seed or Mint is a rapid growing perennial herb with transplants. Since mints readily hybridize between many varieties that grow up to 3 feet tall and are quite different types, plants grown from seed often fail to be invasive. Mint grows best in full sun to partial shade, true to type. For specific cultivars or varieties, buy should be planted early in the growing season and is established plants from reputable sources, take cuttings generally hardy to -20° F. Mint prefers moist soil from known plants, or divide an established plant. conditions, but excess water will promote root and leaf Divide and replant established plants in the spring diseases. Harvest leaves and stems throughout the before growth starts or early in the fall. season, or cut back within an inch of the ground about Planting and Spacing: Sow seeds ¼ inch deep three times a season, just before the plant blooms. and then thin seedlings once they emerge. Transplants should be planted with roots just beneath the soil Varieties surface. Row spacing should be at least 2 feet apart to allow for growth. Use care when selecting mint varieties. The taste Water: Water regularly during the growing and smell varies greatly between varieties. For cold areas season, supplying up to 1 to 2 inches per week, of Utah, peppermint, spearmint, and woolly mints are depending on temperatures, exposure and soil very hardy. All varieties are well suited to areas of Utah conditions. -

Tips for Cooking with Coriander / Cilantro Russian Green Bean Salad

Recipes Tips for Cooking with Coriander / Cilantro • Gently heat seeds in a dry pan until fragrant before crushing or grinding to enhance the flavor. • Crush seeds using a mortar and pestle or grind seeds in a spice mill or coffee grinder. • Seeds are used whole in pickling recipes. • Cilantro is best used fresh as it loses flavor when dried. • Clean cilantro bunches by swishing the leaves in water and patting dry. • For the best color, flavor and texture, add cilantro leaves towards the end of the cooking time. • The stems have flavor too, so tender stems may be chopped and added along with the leaves. • Store cilantro stem in a glass of water in the refrigerator, with a loose plastic bag over the top. Russian Green Bean Salad with Garlic, Walnuts, Basil, Cilantro and Coriander Seed ½ cup broken walnuts ¼ cup firmly packed basil leaves 2 large cloves garlic, peeled and each cut into ¼ cup firmly packed cilantro leaves and several pieces tender stems 4 Tbsp extra-virgin olive oil 1 pound fresh green beans, stems removed 2 Tbsp white wine vinegar and steamed until crisp – tender and cooled 1 Tbsp lemon juice in ice water 1 Tbsp water ½ cup thinly sliced green onions 1 tsp ground coriander seed ½ cup thinly sliced radishes ⅛ to ¼ tsp hot pepper sauce such as Tabasco Salt and freshly ground pepper to taste 2 Tbsp firmly packed parsley leaves and tender stems To prepare dressing, place walnuts and garlic in food processor fitted with knife blade; chop, using pulse control, until evenly fine. Add olive oil, vinegar, lemon juice, water, coriander seed and hot pepper sauce; process until smooth. -

Borage, Calendula, Cosmos, Johnny Jump Up, and Pansy Flowers: Volatiles, Bioactive Compounds, and Sensory Perception

European Food Research and Technology https://doi.org/10.1007/s00217-018-3183-4 ORIGINAL PAPER Borage, calendula, cosmos, Johnny Jump up, and pansy flowers: volatiles, bioactive compounds, and sensory perception Luana Fernandes1,2,3 · Susana Casal2 · José A. Pereira1 · Ricardo Malheiro1 · Nuno Rodrigues1 · Jorge A. Saraiva3 · Elsa Ramalhosa1 Received: 27 June 2018 / Accepted: 28 October 2018 © Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2018 Abstract The aim of the present work was to study the main volatile and bioactive compounds (monomeric anthocyanins, hydrolys- able tannins, total flavonoids, and total reducing capacity) of five edible flowers: borage (Borage officinalis), calendula (Calendula arvensis), cosmos (Cosmos bipinnatus), Johnny Jump up (Viola tricolor), and pansies (Viola × wittrockiana), together with their sensory attributes. The sensory analysis (10 panelists) indicated different floral, fruity, and herbal odors and taste. From a total of 117 volatile compounds (SPME–GC–MS), esters were most abundant in borage, sesquiterpenes in calendula, and terpenes in cosmos, Johnny Jump up, and pansies. Some bioactive and volatile compounds influence the sensory perception. For example, the highest content of total monomeric anthocyanins (cosmos and pansies) was associ- ated with the highest scores of colors intensity, while the floral and green fragrances detected in borage may be due to the presence of ethyl octanoate and 1-hexanol. Therefore, the presence of some volatiles and bioactive compounds affects the sensory perception of the flowers. Keywords Edible flowers · Volatile compounds · Sensory analysis · Bioactive compounds Introduction and fragrances of flowers are analyzed through their vola- tile essential oils [1]. Currently, there are some studies that Edible flowers are becoming more popular in recent years have applied solid-phase microextraction (SPME) method to due to the interest of consumers and professional chefs. -

Sage Salvia Officinalis Garden Sage, Red Sage, Salvia Salvatrix Photo

Sage Salvia officinalis Garden Sage, Red Sage, Salvia salvatrix Photo: LuvlyMikimoto 9/1/07 Botanical Description Salvia officinalis can be used for both culinary and medical needs. Sage generally grows to be approximately a foot tall with leaves one and a half to two inches long. The leaves grow in pairs on the thin stems. Over time the plant eventually becomes woody and much like a shrubbery. All parts of the plant have a strong scent due to the essential oils within them.1 The essential oil is made up of thujone, 1,8-cineole, camphor, borneol, isobutyl acetate, camphene, linalool, alpha- and beta-pinene, viridiflorol, alpa- and beta-caryphyllene. Sage blossoms in August. The flowers are labiate (lip-like) with a light purple, white, or pink color.2 Cultivation Sage grows well in almost all types of garden soil. It thrives in partial shade and warm, dryer soil. Though sage is a perennial, it usually needs to be replanted every few years due to the thinning of the plant.3 Origins The name scientific classification, salvia officinalis comes from the Latin verb salvare meaning to save. It was valued for its healing attributes as illustrated in a common Latin translation, “How can a man die who has Sage in his garden?” Some claim that the Virgin Mary used sage’s “extraordinary virtues” to guide her to Egypt and seek shelter.4 History The Ancients and Arabians considered sage linked to immortality. It was first found northern Mediterranean countries and eventually spread to England, France and Switzerland in the fourteenth century. -

Cool Weather Herbs

www.natureswayresources.com COOL WEATHER HERBS by Susan Gail Wood Herb Society of America/South Texas Unit Plant now in our herb gardens: dill, cilantro, nasturtiums and fennel. I enjoy growing lots of herbs year round to use for fragrance, cooking and beautiful bouquets. My favorite herbs to plant in the fall garden are: cilantro, nasturtiums, borage, fennel and dill. * Harvest basil before it blooms for best flavor. This means taking cuttings several times during the warm growing season to keep blossoms at bay. * Fresh CILANTRO can be used in place of basil for a delightful pesto. Late October and during November are perfect times to start cilantro from seed or plants in your garden. Cilantro has leaves that resemble flat leaf parsley until the plant is ready to flower. Start harvesting beforethe second, thinner set of leaves appear. This is a sign the herb is about to bloom, set seed and die back as is typical of annuals. Cilantro will bolt once the weather warms up next spring. Leave ripe 1 www.natureswayresources.com seed on the plant to fall back in the garden and this herb will be your best volunteer next fall. All the above mentioned favorites will withstand a freeze except for nasturtiums. Water and mulch all your herbs before a hard freeze and cover the nasturtiums. If they don't survive you can always plant more when the danger of frost passes next March. I lovethe cheery flowers they produce which are edible as well as the peppery leaves. * BORAGE is my favorite herb that you might not be growing, but should. -

Entomotoxicity of Xylopia Aethiopica and Aframomum Melegueta In

Volume 8, Number 4, December .2015 ISSN 1995-6673 JJBS Pages 263 - 268 Jordan Journal of Biological Sciences EntomoToxicity of Xylopia aethiopica and Aframomum melegueta in Suppressing Oviposition and Adult Emergence of Callasobruchus maculatus (Fabricus) (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) Infesting Stored Cowpea Seeds Jacobs M. Adesina1,3,*, Adeolu R. Jose2, Yallapa Rajashaker3 and Lawrence A. 1 Afolabi 1Department of Crop, Soil and Pest Management Technology, Rufus Giwa Polytechnic, P. M. B. 1019, Owo, Ondo State. Nigeria; 2 Department of Science Laboratory Technology, Environmental Biology Unit, Rufus Giwa Polytechnic, P. M. B. 1019, Owo, Ondo State. Nigeria; 3 Insect Bioresource Laboratory, Institute of Bioresources and Sustainable Development, Department of Biotechnology, Government of India, Takyelpat, Imphal, 795001, Manipur, India. Received: June 13, 2015 Revised: July 3, 2015 Accepted: July 19, 2015 Abstract The cowpea beetle, Callosobruchus maculatus (Fabricus) (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), is a major pest of stored cowpea militating against food security in developing nations. The comparative study of Xylopia aethiopica and Aframomum melegueta powder in respect to their phytochemical and insecticidal properties against C. maculatus was carried out using a Complete Randomized Design (CRD) with five treatments (0, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0 and 2.5g/20g cowpea seeds corresponding to 0.0, 0.05, 0.075, 0.1 and 0.13% v/w) replicated thrice under ambient laboratory condition (28±2°C temperature and 75±5% relative humidity). The phytochemical screening showed the presence of flavonoids, saponins, tannins, cardiac glycoside in both plants, while alkaloids was present in A. melegueta and absent in X. aethiopica. The mortality of C. maculatus increased gradually with exposure time and dosage of the plant powders. -

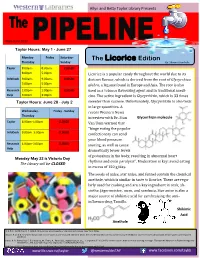

The Licorice Edition

Allyn and Betty Taylor Library Presents May-June 2017 Taylor Hours: May 1 - June 27 Monday- Friday Saturday- The Licorice Edition Thursday Sunday By: Shawn Hendrikx Taylor 8:00am- 8:00am- CLOSED 8:00pm 5:00pm Licorice is a popular candy throughout the world due to its InfoDesk 9:00am- 9:00am- CLOSED distinct flavour, which is derived from the root of Glycyrrhiza 5:00pm 5:00pm glabra, a legume found in Europe and Asia. The root is also Research 1:00pm- 1:00pm- CLOSED used as a tobacco flavouring agent and in traditional medi- Help 3:00pm 3:00pm cine. The active ingredient is Glycyrrhizin, which is 33 times Taylor Hours: June 28 - July 2 sweeter than sucrose. Unfortunately, Glycyrrhizin is also toxic in large quantities. A Wednesday- Friday - Sunday recent Western News Thursday interview with Dr. Stan Glycerrhizin molecule Taylor 8:00am-5:00pm CLOSED Van Uum warned that “binge eating the popular InfoDesk 9:00am- 5:00pm CLOSED confectionary can send your blood pressure Research 1:00pm-3:00pm CLOSED soaring, as well as cause Help dramatically lower levels of potassium in the body, resulting in abnormal heart Monday May 22 is Victoria Day rhythms and even paralysis”. Moderation is key: avoid eating The Library will be CLOSED in excess of 150 g/day. The seeds of anise, star anise, and fennel contain the chemical anethole, which is similar in taste to licorice. These are regu- larly used for cooking and are a key ingredient in arak, ab- sinthe, Ja germeister, ouzo, and sambuca. Star anise is also a major source of shikimic acid for synthesizing the anti- influenza drug Tamiflu. -

Building Big Flavor

BUILDING BIG FLAVOR Watching your sodium intake? Balancing flavors is the key to a flavorful meal when reducing the salt in a dish. Think about adding these flavor enhancers instead of reaching for the salt shaker! Sweet Bitter Acidic Umami (Savory) Brings balance and Balances sweetness Brings brightness Makes a dish savory or roundness to a dish by and cuts richness - and adds a salty meaty tasting and balancing acidity and best used as flavor that enhances flavors - reach bitterness and background flavor balances for these before salt! highlighting other flavors sweetness Fruit juices, Nectars, Greens (Kale, Lemon, Lime, Tomato Products Concentrates, Chard, Dandelion, Orange and (especially canned, like Reductions, Caramelized Chicory, Watercress, Pineapple Juice, paste) Soy Sauce, Onions, Carrots, Sweet Arugula) Broccoli Vinegars, Wine, Mushrooms (especially Potatoes, Butternut Rabe, Broccoli, Tamarind, dried) Cured or brined Squash, Roasted Cabbage, Brussels Pickled Foods, foods (olives) Seaweed, Peppers, Honey, Maple Sprouts, Asparagus, Cranberries, Sour Fish Sauce, Fermented Syrup, Molasses, Dried Some Mustards, Cherries, Tomato Foods (Miso, Fermented Fruits, Tomato Paste, Grapefruit, Citrus Products Black beans, Sauerkraut) Beets, Reduced Vinegars, Rind/Zest, Beer, Aged cheeses (Parmesan, Wine, Wine, Teas (black & Blue, Gouda) Liquid Amino green) Acids, Seafood (especially dried), Worcestershire Sauce, Anchovy, Beef, Pork (especially cured), Chicken Don’t forget to read nutrition labels and watch for foods that are commonly high -

The Height of Its Womanhood': Women and Genderin Welsh Nationalism, 1847-1945

'The height of its womanhood': Women and genderin Welsh nationalism, 1847-1945 Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Kreider, Jodie Alysa Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 09/10/2021 04:59:55 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/280621 'THE HEIGHT OF ITS WOMANHOOD': WOMEN AND GENDER IN WELSH NATIONALISM, 1847-1945 by Jodie Alysa Kreider Copyright © Jodie Alysa Kreider 2004 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY In Partia' Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2004 UMI Number: 3145085 Copyright 2004 by Kreider, Jodie Alysa All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI UMI Microform 3145085 Copyright 2004 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. -

Natural Beauty Alchemy : Make Your Own Organic

AN IDEA REMAINS AN IDEA, UNTIL IT IS CRAFTED WITH PASSION! Through the challenges, with a lot of time, effort, and determination, this project came together. For my family, who supported and motivated me when I needed it most; for my beautiful mother, who did everything only a mother can do; for my friends, who were amazing first enthusiasts; and for every natural beauty believer, a heartfelt thank you. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION UNDERSTANDING NATURAL SKIN CARE AND INGREDIENTS Skin Skin Care Categories Ingredients RECIPES Making Your Own Skin Care Products Facial Masks and Scrubs Cleansers and Makeup Removers Toners Evening Oils and Serums Facial Creams and Sunscreen Eye Care Neck Care Body Care Hand Care Foot and Heel Care Hair Care Perfumes and Scented Sprays BUYING COMMERCIAL SKIN CARE PRODUCTS Debated Ingredients Animal-Derived Ingredients Certifications and Seals SUBSTITUTION CHART GLOSSARY DISCLAIMER ACKNOWLEDGMENTS INDEX INTRODUCTION What Is Beauty? Beauty is a perceptual concept that grows with individuals of every society and culture. As we begin to understand what it means and grasp its dimensions, we learn to appreciate it and search for it in every facet of our lives. We also attempt to bring beauty into our daily lives by incorporating beautiful things into our surrounding environment and by trying to beautify our own appearance. Most women, men, and children have an innate desire to look and feel beautiful inside and out, and there is a certain harmony that often links inner and outer beauty and reflects the result to the outside. Each person defines and implements beauty in a different way, but despite the subjectivity, a huge platform remains common ground for most people in search of a more “beautiful” look. -

The Case of Michael Du Val's the Spanish English Rose

SEDERI Yearbook ISSN: 1135-7789 [email protected] Spanish and Portuguese Society for English Renaissance Studies España Álvarez Recio, Leticia Pro-match literature and royal supremacy: The case of Michael Du Val’s The Spanish English Rose (1622) SEDERI Yearbook, núm. 22, 2012, pp. 7-27 Spanish and Portuguese Society for English Renaissance Studies Valladolid, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=333528766001 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Pro-match literature and royal supremacy: The case of Michael Du Val’s The Spanish English Rose (1622) Leticia Álvarez Recio Universidad de Sevilla ABSTRACT In the years 1622-1623, at the climax of the negotiations for the Spanish-Match, King James enforced censorship on any works critical of his diplomatic policy and promoted the publication of texts that sided with his views on international relations, even though such writings may have sometimes gone beyond the propagandistic aims expected by the monarch. This is the case of Michael Du Val’s The Spanish-English Rose (1622), a political tract elaborated within court circles to promote the Anglo-Spanish alliance. This article analyzes its role in producing an alternative to the religious and imperial discourse inherited from the Elizabethan age. It also considers the intertextual relations between Du Val’s tract and other contemporary works in order to determine its part within the discursive network of the Anglican faith and political absolutism.