Historical Society Quarterly, No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Remarks at a Democratic National Committee Rally in Las Vegas, Nevada October 22, 2010

Oct. 22 / Administration of Barack Obama, 2010 Remarks at a Democratic National Committee Rally in Las Vegas, Nevada October 22, 2010 The President. Hello, Vegas! It is good to be some obstacles, to have to overcome some stuff, back in Vegas. It is good to be back in Nevada. that things don’t always work out perfectly. Oh, I am fired up. Are you fired up? But because of that, because he remembers There are a couple of folks that I want to where he came from, it means that he thinks ev- make mention of. First of all, Congresswoman ery single day about how am I going to give the Shelley Berkley is in the house. An outstanding folks in Nevada a better shot at life. freshman Congresswoman, Dina Titus is here. And so I want everybody here to understand Senate Majority Leader Steven Horsford is in what’s at stake. the house. Former Governor Bob Miller is Audience members. Obama! Obama! Obama! here. My dear friend, my Senator from Illinois, The President. I appreciate everybody saying Dick Durbin is here to help his partner Harry “Obama,” but I want everybody to say “Harry! Reid. Harry! Harry!” And I want to say to all the folks from Orr Audience members. Harry! Harry! Harry! school, thank you so much for your hospitality, The President. That’s right. I need partners and thanks to Principal George Leavens. Thank like Harry. And I need partners like Dina Titus. you. And I need partners like Shelley Berkley. Look, I am happy to see all of you. -

The Role and Contributions of Clark County, Nevada School District Superintendents, 1956 – 2000

Public Policy and Leadership Faculty Publications School of Public Policy and Leadership 2016 Development of a School District: The Role and Contributions of Clark County, Nevada School District Superintendents, 1956 – 2000 Patrick W. Carlton University of Nevada, Las Vegas, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/sea_fac_articles Part of the Educational Leadership Commons, Education Policy Commons, and the Elementary and Middle and Secondary Education Administration Commons Repository Citation Carlton, P. W. (2016). Development of a School District: The Role and Contributions of Clark County, Nevada School District Superintendents, 1956 – 2000. 1-156. https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/sea_fac_articles/403 This Monograph is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Monograph in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Monograph has been accepted for inclusion in Public Policy and Leadership Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Development of a School District: The Role and Contributions of Clark County, Nevada School District Superintendents 1956 – 2000 By Patrick W. Carlton, Ph.D. Professor of Public Administration University of Nevada, Las Vegas © 2016 by Patrick W. Carlton Patrick W. -

Developing a National Action Plan for Eliminating Sex Trafficking

Developing a National Action Plan for Eliminating Sex Trafficking Final Report August 16, 2010 Prepared by: Michael Shively, Ph.D. Karen McLaughlin Rachel Durchslag Hugh McDonough Dana Hunt, Ph.D. Kristina Kliorys Caroline Nobo Lauren Olsho, Ph.D. Stephanie Davis Sara Collins Cathy Houlihan SAGE Rebecca Pfeffer Jessica Corsi Danna Mauch, Ph.D Abt Associates Inc. 55 Wheeler St. Cambridge, MA 02138 www.abtassoc.com Table of Contents Preface ..................................................................................................................................................ix Acknowledgements....................................................................................................................xii Overview of the Report.............................................................................................................xiv Chapter 1: Overview ............................................................................................................................1 Project Background......................................................................................................................3 Targeting Demand .......................................................................................................................3 Assumptions about the Scope and Focus of the National Campaign...........................................5 The National Action Plan.............................................................................................................6 Scope of the Landscape Assessment............................................................................................7 -

Selected Highlights of Women's History

Selected Highlights of Women’s History United States & Connecticut 1773 to 2015 The Permanent Commission on the Status of Women omen have made many contributions, large and Wsmall, to the history of our state and our nation. Although their accomplishments are too often left un- recorded, women deserve to take their rightful place in the annals of achievement in politics, science and inven- Our tion, medicine, the armed forces, the arts, athletics, and h philanthropy. 40t While this is by no means a complete history, this book attempts to remedy the obscurity to which too many Year women have been relegated. It presents highlights of Connecticut women’s achievements since 1773, and in- cludes entries from notable moments in women’s history nationally. With this edition, as the PCSW celebrates the 40th anniversary of its founding in 1973, we invite you to explore the many ways women have shaped, and continue to shape, our state. Edited and designed by Christine Palm, Communications Director This project was originally created under the direction of Barbara Potopowitz with assistance from Christa Allard. It was updated on the following dates by PCSW’s interns: January, 2003 by Melissa Griswold, Salem College February, 2004 by Nicole Graf, University of Connecticut February, 2005 by Sarah Hoyle, Trinity College November, 2005 by Elizabeth Silverio, St. Joseph’s College July, 2006 by Allison Bloom, Vassar College August, 2007 by Michelle Hodge, Smith College January, 2013 by Andrea Sanders, University of Connecticut Information contained in this book was culled from many sources, including (but not limited to): The Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame, the U.S. -

Administration of Barack H. Obama, 2010 Remarks At

Administration of Barack H. Obama, 2010 Remarks at a Democratic National Committee Rally in Las Vegas, Nevada October 22, 2010 The President. Hello, Vegas! It is good to be back in Vegas. It is good to be back in Nevada. Oh, I am fired up. Are you fired up? There are a couple of folks that I want to make mention of. First of all, Congresswoman Shelley Berkley is in the house. An outstanding freshman Congresswoman, Dina Titus is here. Senate Majority Leader Steven Horsford is in the house. Former Governor Bob Miller is here. My dear friend, my Senator from Illinois, Dick Durbin is here to help his partner Harry Reid. And I want to say to all the folks from Orr school, thank you so much for your hospitality, and thanks to Principal George Leavens. Thank you. I am happy to see all of you. And I have to say, for some reason, whenever I'm coming to Vegas, suddenly, a whole bunch of folks on my staff want to come with me. I don't know. [Laughter] Suddenly, there are no seats on Air Force One. It's all crowded. [Laughter] So I've already told them they've got to behave themselves a little bit while they're here. But the main reason I'm here, the main reason I need you fired up, is because in just 11 days, you have the chance to set the direction of this State and this country, not just for the next 5 years, not just for the next 10 years, but for the next several decades. -

Spring Creek Lamoille Master Plan 2012 Review\Final Copy (Corrected) - SCLMP.Doc

Elko County, Nevada Spring Creek / Lamoille Master Plan 2012 Pg. 1 Planning Commission, County Commissioners Approvals 1 Spring Creek / Lamoille Master Plan Index 2 thru 5 Spring Creek / Lamoille Master Plan Index Section I Introduction 6 General Disclosure 7 History 8 Statutory Provisions 10 Physical Characteristics 11 Climate 11 Vegetation 12 Soil Limitations 12 Drainage and Flood Plains 13 Public Facilities and Services 14 Education / Schools 14 Recreation 14 Fire Protection 14 Law Enforcement / Police Protection 14 Solid Waste Disposal 15 Utilities 15 Public Development of the Master Plan 15 Master Plan Boundaries 16 Plan Area I 17 Plan Area II 17 Plan Area III 18 Plan Area IV 19 Overall Plan Area 20 Summary of Workshops and Public Hearings 22 Public Concerns 32 General Public Concerns 32 Specific Public Concerns 32 Spring Creek / Lamoille Master Plan Index Section II Master Plan Policies 33 Agricultural 33 Residential 33 Recreation 34 Public 34 Pg. 2 Traffic Circulation 34 Public Facilities 35 Population (1997/2005/2012) 35 General 35 Subdivision Regulations 36 Consistency 36 General Implementation 36 Plan Implementation 37 Zoning Regulations 37 Guidelines 37 Land use designation and Zoning districts 37 Special Designations and Provisions 37 Commercial (Restricted) 37 Commercial Lamoille and Jiggs Highways 38 Commercial Adjacent to Lamoille Highway 38 Corral Lane Re-alignment 38 Boyd Kennedy Road/ Lamoille Hwy Intersection 38 Architectural Restrictions 39 Lamoille Cemetery 39 Acreage Restrictions (Residential) (1997) 39 Planned Cluster -

A Catholic History of the Heartland: the Rise and Fall of Mid-America: a Historical Review

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons History: Faculty Publications and Other Works Faculty Publications 1-2016 A Catholic History of the Heartland: The Rise and Fall of Mid- America: A Historical Review Theodore Karamanski Loyola University Chicago, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/history_facpubs Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Karamanski, Theodore. A Catholic History of the Heartland: The Rise and Fall of Mid-America: A Historical Review. Studies in Midwestern History, 2, 1: 1-12, 2016. Retrieved from Loyola eCommons, History: Faculty Publications and Other Works, This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History: Faculty Publications and Other Works by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. © Midwestern History Association, 2016. S T U D I E S I N M I D W E S T E R N H I S T O R Y VOL. 2, NO. 1 January, 2016 A CATHOLIC HISTORY OF THE HEARTLAND: THE RISE AND FALL OF MID-AMERICA: A HISTORICAL REVIEW Theodore J. Karamanski1 In many ways it was an inauspicious moment to organize a new historical enterprise. In 1918 the United States was deeply engaged in a conflict so monstrously all-consuming it was simply referred to as “the Great War.” The population of the nation, even in the heavily ethnic and for- eign-born Midwest, was mobilized for war. -

I Have Details- Concerning Dave Burgess- the World President

i have details- concerning dave burgess- the world president & brothel owner of the hells angel on trial for child pornography- and want to take the witness stand to testify against him. i also have been trying to gather proof about dave burgess and troy regas child pornography ring since 1994 and i have information that shows that dave burgess is not the only one who is involved with the hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of pictures of children being sexually abused that was found in dave burgess computer-- i have been searching for proof since 1994 when i used to work at the mustang ranch (brothel in 1994- i walked over by the bridge where dave burgess old bridge brothel is located next to the old mustang ranch and discovered a child pornography magazine laying next to the water by the bridge and i was appalled--- i regret that i didn't take the magazine and keep it for proof-- because when i saw it i was so much horrified and shocked that i threw it in the river and ran away as fast as i could, crying uncontrollably and really freaking out--i told some anna marie - who is now deceased ( she is johnny collettis brother and shirley collettis daughter, and she was a close friend with me for the short tyme i knew her before she died, and when i told her about what i saw she began crying and told me never to tell anyone about this or i would be in danger and i became angry and asked her if she was involved in these things , molesting and pictures of little children... -

San Diego Indian 15

want this on my motorcycle, my car, my mountain QUICK Throttle MAGAZINE PO Box 3062 • Dana Point, CA 92629 bike, everywhere! 949-388-3695 AUGUST 2014 [email protected] • www.quickthrottle.com Now about that sound...you’ve heard the clip, you’ve maybe heard it revving on the dyno-type platform they’ve been setting up on the Livewire tours. Well, it doesn’t quite sound the same on the road, but close. Yes, it’s got the turbine sound, just not enough of it. I told the H-D guys, “When you finally ship these things, make the sound as raunchy as possible.” Sure it’s cool, but I want more of it. If I can’t set off car alarms with my pipes, I gotta have something right? Now I have heard it’s actually louder than the Zero and other electric bikes. H-D Sportbike looks aside, we were very intrigued. Why? claims they “designed” the sound that way. They We Ride Harley-Davidson’s Because we knew from the Tesla Roadster in 2008 also told me the sound can be affected by how the that this technology could provide “instant torque” gears are cut. I did notice, when riding around with New Electric Motorcycle and remain very fast throughout the entire power those other Livewire’s, that it was very reminiscent curve. Our interest was also piqued when we heard of the scene in “Return of the Jedi” when they’re By CD, Editor of QT Magazine the sound it made, or a recording of it at least - it sounded like a cross between a turbine engine and That’s right, we rode it the Jetson’s flying car. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form 1

FHR-8-300 (11-78) United States Department of the interior Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections_______________ 1. Name__________________ historic Virginia Street Bridge_______________________ and/or common Same 2. Location K rV: street & number Ar.rnss Truckee River At Virginia Street not for publication city, town Reno vicinity of____congressional district at large state Nevada code 32 county Washoe code 031 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public ^ occupied agriculture museum building(s) private unoccupied commercial park X structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process X yes: restricted government scientific y being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military other: 4. Owner of Property name State of Nevada, Department of Transportation street & number 1263 S . Stewart city,town Carson City vicinity of state Nevada 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. 3ame as above street & number city, town state 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title Nevada Historic Engineering Site has this property been determined elegible? yes no Inventory date 5/8/79 federal state county local depository for survey records History of Engineering Program . Texas Tech University city, town Lubbock state Texas 7. Description Condition Check one Check one _ X. excellent deteriorated x unaltered _ X- original site good ruins altered moved date fair unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance Built in 1905, the Virginia Steet Bridge is a two span bridge across the Truckee River at Virginia Street in Reno. -

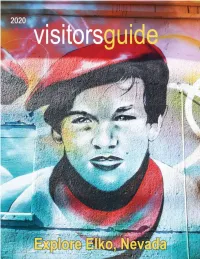

2020 Elko Guide

STAY & PLAY MORE THAN 17,000 SQUARE FEET OF PURE GAMING SATISFACTION AWAITS YOU AT RED LION HOTEL & CASINO. FIND A WIDE VARIETY OF ALL THE HOTTEST SLOTS AND AN EXCITING SELECTION OF TABLE GAMES INCLUDING BLACKJACK, 3CARD POKER, CRAPS, ROULETTE, AND MORE. YOU’LL ENJOY THE FINEST SPORTS BOOK AND THE ONLY LIVE POKER ROOM IN ELKO. GC: 2050 Idaho Street | Elko, NV 89801 | 775-738-8421 | 800-621-1332 RL: 2065 Idaho Street | Elko, NV 89801 | 775-738-2111 | 800-545-0444 HD: 3015 Idaho Street | Elko, NV 89801 | 775-738-8425 | 888-394-8303 wELKOme to Elko, Nevada! hether you call Elko home, are passing through or plan to come and stay a while, we are confident you’ll find something Elko Convention & Wnew and exciting as you #ExploreElko! Visitors Authority 2020 Elko is a vibrant community offering great Board of Directors food; a wide selection of meeting, conference and lodging accommodation options; wonderful events Matt McCarty, Chair throughout the year; art, museums and historical Delmo Andreozzi attractions and an abundance of outdoor recreation Dave Zornes Toni Jewell opportunities. Chip Stone Whether you’re a trail-blazing, peak bagging, galloping adrenaline junkie or an art strolling, line casting, Sunday driving seeker, your adventure starts Follow us on here, the 2020 Visitors Guide, showcasing all the Elko social media! area has to offer. #ExploreElko, @ExploreElko On behalf of the Elko Convention & Visitors Authority and the City of Elko, thank you for being here and we wish you a safe, wonderful visit! Katie Neddenriep Reece Keener Executive Director, Mayor, Elko Convention & City of Elko Visitors Authority 2020 Elko Visitor’s Guide 1 lko is in the northeastern corner of the State of Nevada, situated on the Humboldt River between Reno, Nevada and Salt Lake City, Utah. -

Hiv Testing Policies Toward Prostitutes in Nevada

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-2004 Vectors, polluters, and murderers: Hiv testing policies toward prostitutes in Nevada Cheryl L Radeloff University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Radeloff, Cheryl L, "Vectors, polluters, and murderers: Hiv testing policies toward prostitutes in Nevada" (2004). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 2605. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/3mq9-ejlz This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VECTORS, POLLUTERS, AND MURDERERS: HIV TESTING POLICIES TOWARD PROSTITUTES IN NEVADA by Cheryl L. Radeloff Bachelor of Arts Bowling Green State University 1990 Master of Arts University of Toledo 1996 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology Department of Sociology College of Liberal Arts Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas December 2004 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 3181639 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted.