Skill Tests 1976 1977

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of Certain Time, Motion, and Time-Motign

AN ANALYSIS OF CERTAIN TIME, MOTION, AND TIME-MOTIGN FACTORS IN EIGHT ATHLETIC SPORTS A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University 9y ROBERT JAI FRANCIS, B. S., M.A. The Ohio!State University 1952 Approved by Adviser I TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER Page I. INTRODUCTION........................................... 1 Title of the Study........................ 1 Purposes and Values of the Study................... 1 Purposes.................... 1 Values ......................................... 7 Related Literature..................................... 10 Limitations of the Study............................... 12 II. METHOD OF PROCEDURE................ .................... 13 Apparatus and Equipment Used........................ 13 Establishing Validity and Reliability of the Apparatus........................................... 15 III. BADMINTON................................................. 20 Method of Procedure in Badminton. .......... 20 Findings in Badminton.................... 23 Time Factors ........ 24 Motion Factors................................ 25 Time-Motion Factors............................... 28 Recapitulation.................... 30 Implications for Teaching .............30 IV. BASEBALL................................................. 35 Method of Procedure in Baseball ..................... 35 Findings in Baseball............ 37 Time Factors..................................... 33 Motion Factors........... .......... -

1 Directives

1 1. General Competition Schedule with venues (All Sports) No November December Sport 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Opening Ceremony 1 Aquatics Diving Open Water Swimming Water Polo 2 Archery 3 Arnis 4 Athletics 5 Badminton 6 Baseball Softball 7 Basketball 8 Billiards and Snookers 9 Bowling 10 Boxing 11 Canoe/Kayak/Traditional Boat Race 12 Chess 13 Cycling Nov 14 Dancesport 15 E-Sports 16 Fencing 17 Floorball 18 Football 19 Golf Dec 20 Gymnastics 21 Handball (Beach) 22 Hockey (Indoor) 23 Ice Hockey 24 Ice Skating 25 Jujitsu 26 Judo 27 Karatedo 28 Kickboxing 29 Kurash 30 Lawnballs Petanque 31 Modern Pentathlon 32 Muay 33 Netball 34 Obstacle Race Sports 35 Pencak Silat 36 Polo 37 Rowing 38 Rugby 39 Sailing & Windsurfing 40 Sambo 41 Sepak Takraw 42 Shooting 43 Skateboarding 44 Soft Tennis 45 Squash 46 Surfing 47 Table Tennis 48 Taekwondo 49 Tennis 50 Triathlon Duathlon 51 Underwater Hockey 52 Volleyball (Beach) Volleyball (Indoor) 53 Wakeboarding & Waterski 54 Weightlifting 55 Wrestling 56 Wushu Closing Ceremony 2 2. Submission of Entries Entry by Number – Deadline for submission of Entry by Number Forms is March 15, 2019 at 24:00 hours Philippine time (GMT+8) Entry by Name – Deadline for submission of Entry by Name Forms is September 02, 2019 at 24:00 hours Philippine Time (GMT +8) 3. Eligibility 3.1 To be eligible for participation in the SEA Games, a competitor must comply with the SEA Games Federation (SEAGF) Charter and Rules as well as Rule 40 and the By-law to Rule 40 of the Olympic Charter (Participation in the Games). -

Badminton Study Guide HISTORY: • a Very Long History for One of The

Badminton Study Guide HISTORY: A very long history for one of the Olympics newest sports! Badminton took its name from Badminton House in Gloucestershire, the ancestral home of the Duke of Beaufort, where the sport was played in the last century. Modern history of badminton began in India with a game known as Poona. Gloucestershire is now the base for the International Badminton Federation. Badminton first appeared as an Olympic sport at the 1992 games in Barcelona, Spain. RULES OF THE GAME: The first serve of the game always begins in the right service box. The serve must go diagonally into the service box across the net and only the player in that service box may return the serve. The receiving player returns the shuttle and it is hit back and forth until someone fails to return it successfully. Games are played to 21 and rally scoring is used. The team winning the rally scores the point. When the serving team wins the rally, they earn a point. They switch service boxes and serve again. The same player serves. When the receiving team wins a rally, they gain a point and the right to serve. When you win the serve and your score is zero or an even number, the player in the right service box serves. If your score is an odd number the player in the left service box serves. You may not reach over the net in order to hit the birdie. The serve must be hit underhand and below the waist The shuttle may only be hit once per side. -

Sport at St John's

Sport at St John’s How important is it in your life? We asked - Do you like playing sport? YOU SAID –YES WE DO!! Yr 3 - 30/30 Yr 4 – 28/30 Yr 5 – 28/30 Yr 6 – 29/30 Total – 115 out of 120 = 95.83% Those who said no said: • “It’s not my thing” • “Boring” • “I’m very bad at it” • “I prefer computers” Those who said yes • “Awesome”, “I like being active”, “Interesting and intense” • “Get to go outside in the hot weather”, “It’s good for me” • “I like keeping my six pack”, “You get fit”, “Playground learning instead of lessons” • “Helps you exercise”, “Keeps you healthy”, “Enjoyable”, “Makes you strong”, “I like running around” • “You can just do it”, “I feel like a different person”, “Brings out the competitive side of me” • “I’m good at running”, “I like team leadership”, “Exciting”, “Epic”, “Something new to learn” • “It gives you energy”, “Because I do”, “Something I can do in my spare time”. But mostly you said •BECAUSE IT’S FUN!!!!! What’s your Favourite Sport? • Year 3 picked 12 different sports – Football (11), Swimming (6), Tennis (3), Cricket (2), and 1 each for Climbing, Gymnastics, Basketball, Sack Race, Badminton, Roller Skating, Ballet and Karate. • Year 4 picked 11 different sports – Football (10), Tennis (4), Swimming (3), Gymnastics (3), Athletics (3), Basketball (2), Badminton (2) and 1 each for golf, horse riding, rounders and cricket. • Year 5 picked 11 different sports – Football (13), Swimming (3), Basketball (3), Netball (3), Cricket (2) and 1 each for Gymnastics, Skateboarding, Rugby, Table Tennis, Tennis and Athletics. -

RHYTHMIC GYMNASTICS Games-Time Guide DISCLAIMER All Information in This Guide Was Correct at the Time of Going to Press

RHYTHMIC GYMNASTICS Games-time Guide DISCLAIMER All information in this guide was correct at the time of going to press. Changes to schedules, procedures, facilities and services, along with any other essential updates, will be communicated to teams by competition management if required. Changes to the competition schedule will also appear on the Games-time Website, while any changes to the training schedule will be communicated by the Sport Information Centre in the Athletes Village. Welcome The Baku 2015 European Games will welcome around 6,000 athletes, 3,000 supporting team officials and 1,600 technical officials from across Europe to participate in elite-level sport competition. We aim to provide all participants with optimal conditions so that they are able to perform at their best. This guide will help with those preparations and Games-time operations as it provides key information including the relevant competition rules and format, medal events, competition schedule and key dates. Each audience – athletes, team officials and technical officials – also has their own dedicated section within the guide that includes the information that is relevant to them. The guide also includes details of the relevant venue, medical, anti- doping, training and competition related services, as well as the key policies and procedures that will be in place during the Games for each client group. We hope that this guide helps with your planning in the weeks remaining before the European Games. Hard copies of this Games-time Guide will be provided to each client group upon arrival in Baku. We look forward to welcoming you to Baku for 17 days of competition that puts sport first and sets a tradition for the European Games that follow. -

Badminton Bingo

Badminton Bingo Submitted by Jo Moore Bailey Directions: 1. Complete 5 warm up activities each day. Cross out an activity once completed 2. Identify one component of fitness (skill or health) worked by the activity performed in each square. Write it in the square. Run from the net Hold a plank for Hit the 10 push ups Run around the to the back line 30 seconds shuttlecock 5x to fieldhouse 1x 5x. a partner on 5 You must face different courts the net at all times. 20 Plank Jacks Hit the Side shuffle 30x of any Crab walk from shuttlecock to a across the width abdominal one end of the partner 10x of 4 badminton exercise badminton court between the net courts and back. (crunches, to the other and short service bicycles etc) line only Run across the 20 Jumping Jacks Start in the Bear crawl from Complete a rally basketball court center of the the back of the of 20 consecutive and back while court. Run to court to the net shots. If the tapping a each corner of and back shuttlecock is not shuttlecock on the court and returned, start your racquet back to the over. middle, facing the net Hit the Run around the Hit the shuttle up Facing the net, 30 Skaters shuttlecock 5x to fieldhouse 2x 10x, change run from one side a partner on 8 which hand holds of the court to different courts the racquet after the other side 5x each hit as quickly as you can 10 Squats Hit the 20 Bird Dogs, 20x of any Hit the shuttlecock past hold each one for abdominal shuttlecock 7x to the short service 3 seconds exercise a partner on 6 line (crunches, different courts 10x bicycles -

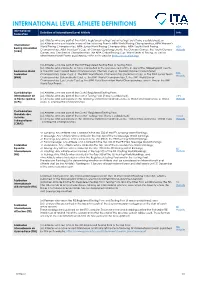

International Level Athlete Definitions

INTERNATIONAL LEVEL ATHLETE DEFINITIONS International Definition of International Level Athlete Links Federation (a) Athletes who are part of the AIBA’s Registered Testing Pool or Testing Pool (if one is established); or (b) Athletes who participate in any of the following Events: AIBA World Boxing Championships, AIBA Women’s International World Boxing Championships, AIBA Junior World Boxing Championships, AIBA Youth World Boxing AIBA Boxing Association Championships, AIBA President’s Cup, all Olympic Qualifying Events, the Olympic Games, the Youth Olympic Website (AIBA) Games, any Continental Championships, the AIBA Global Boxing Cup, World Series of Boxing, as well as other International Events published by AIBA on its website (http://www.aiba.org). (a) Athletes who are part of the BWF Registered Testing Pool or Testing Pool; (b) Athletes who compete, or have competed in the previous 12 months, in any of the following BWF Events: Badminton World a. The BWF Men’s World Team Championships (Thomas Cup); b. The BWF Women’s World Team BWF Federation Championships (Uber Cup); c. The BWF World Team Championships (Sudirman Cup); d. The BWF Junior Team Website (BWF) Championships (Suhandinata Cup); e. The BWF World Championships; f. The BWF World Junior Championships (Eye Levels Cup); g. The BWF Para Badminton World Championships; and h. Any of the BWF World Tour Events. Confédération (a) Athletes who are part of the CMAS Registered Testing Pool; Internationale de (b) Athletes who are part of the CMAS Testing Pool (if one is established); CIPS la Pêche Sportive (c) Athletes who participate in the following CMAS International Events: a. World Championships; b. -

Hockey Chess Fitness Karate Rugby Soccer Badminton

KING’S SPORTS SCHOOL TERM 1 - ENROLMENT Please tick desiredS option(s) HOCKEY 11 Sessions $198 Group Classes TENNIS Years 1 – 3 Wed 5 Feb to 16 Apr 3.15 - 4.00 11/10 Sessions $198 / $180 Years 4 – 8 Wed 5 Feb to 16 Apr 4.00 - 4.45 Mini Pros Jun Mon 3 Feb to 14 Apr 12.35 – 1.20 Mini Pros Jun Tues 4 Feb to 15 Apr 12.35 – 1.20 CHESS Smashers Int Wed 5 Feb to 16 Apr 12.35 – 1.20 $50 Group Classes 10 Mini Pros Thur 13 Feb to 17 Apr 12.35 – 1.20 Played Before Thurs 13 Feb to 17 Apr 12.35 – 1.20 Jun Juniors Fri 7 Feb to 11 Apr 12.35 – 1.20 10 All Courters Fri 7 Feb to 11 Apr 12.35 – 1.20 Sen Beginners Wed 5 Feb to 16 Apr 12.35 – 1.20 CRICKET FITNESS 11/10 Sessions $198 / $180 Group Classes (depending on numbers 11 Sessions $198 Years 3 -4 Mon 3 Feb to 14 Apr 12.35 – 1.20 Years 1 - 4 Mon 3 Feb to 14 Apr 12.35 – 1.20 Years 4 – 5 Tues 4 Feb to 15 Apr 12.35 – 1.20 Years 1 – 4 Tues 4 Feb to 15 Apr 3.15 – 4.00 Years 1 – 3 Wed 5 Feb to 16 Apr 12.35 – 1.20 Years 5 – 8 Tues 4 Feb to 15 Apr 4.00 – 4.45 10 Years 1 – 2 Thurs 13 Feb to 17 Apr 12.35 – 1.20 10 Years 5 – 8 Fri 7 Feb to 11 Apr 12.35 – 1.20 KARATE 11/10 Sessions $198/ $180 Group Classes BASKETBALL Years 1 – 4 Mon 3 Feb to 14 Apr 3.15 – 4.00 11/10 Sessions from $198 to $246 see Page 12 Years 1 – 4 Tues 4 Feb to 15 Apr 3.15 – 4.00 Years 5 – 6 Mon 3 Feb to 14 Apr 12.35 – 1.20 Years 1 – 4 Wed 5 Feb to 16 Apr 3.15 – 4.00 Years 3 – 4 Mon 3 Feb to 14 Apr 3.30 – 4.15 Years 1 – 4 Thurs 13 Feb to 17 Apr 3.15 – 4.00 Years 1 – 2 Tues 4 Feb to 15 Apr 12.35 – 1.20 Years 5 – 8 Tues 4 Feb to 15 Apr 4.00 – 4.45 -

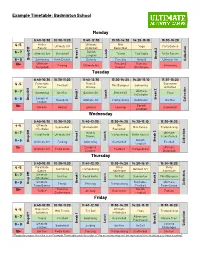

Example Timetable: Badminton School Monday Tuesday

Example Timetable: Badminton School Monday 9:40–10:30 10:30–11:20 11:40–12:30 13:30–14:20 14:20–15:10 15:30–16:20 Roller Ultimate Mini 4 -5 Ultimate Art Yoga Party Games Racers Dodgeball Basketball Danish 6 – 7 Ultimate Art Benchball Tennis Tag Rugby Roller Racers Longball Lunch Break 1 Break 2 Drop Off Drop 8 – 9 Swimming Kwik Cricket Zorbing Fencing Netball Ultimate Art Collection Ultimate Escape & Dancing 10+ Zorbing Ultimate Art Swimming Dodgeball Evasion Challenges Tuesday 9:40–10:30 10:30–11:20 11:40–12:30 13:30–14:20 14:20–15:10 15:30–16:20 4 -5 Parachute Move & Baseroom Football Mini Olympics Swimming Games Groove Activities Ultimate 6 – 7 Swimming Uni Hoc Outdoor Art Benchball Yoga Inflatbales Lunch Break 1 Escape & Break 2 8 – 9 Off Drop Rounders Ultimate Art Trampolining Badminton Uni Hoc Collection Evasion Danish 10+ Uni Hoc Netball Zorbing Fencing Basketball Longball Wednesday 9:40–10:30 10:30–11:20 11:40–12:30 13:30–14:20 14:20–15:10 15:30–16:20 4 -5 Ultimate Mini Scatterball Ultimate Art Mini Tennis Trampolining Inflatbales Basketball 6 – 7 Move & Ultimate Pedal Karts Ultimate Art Trampolining Roller Racers Groove Team Games Lunch Break 1 Danish Break 2 8 – 9 Off Drop Ultimate Art Zorbing Swimming Scatterball Football Collection Longball Escape & Ultimate 10+ Ultimate Art Pedal Karts Football Trampolining Evasion Dodgeball Thursday 9:40–10:30 10:30–11:20 11:40–12:30 13:30–14:20 14:20–15:10 15:30–16:20 4 -5 Parachute Story Story Swimming Trampolining Outdoor Art Games Adventure Adventure Ultimate 6 – 7 Uni Hoc Pedal Karts -

Comparison of Particular Anthropometric and Fitness Variables of Badminton and Handball Players, Manipur

© 2018 JETIR December 2018, Volume 5, Issue 12 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) COMPARISON OF PARTICULAR ANTHROPOMETRIC AND FITNESS VARIABLES OF BADMINTON AND HANDBALL PLAYERS, MANIPUR KSHETRIMAYUM BIRBAL SINGH Dept. of Physical Education, Health Education & Sports, D.M. College of Science, Manipur, India Abstract Aim of the study was to compare the particular anthropometric and fitness variables of badminton and handball players, Manipur of 60/60 male players ranged from 18 to 22 years. The data was analysed by descriptive statistics and t-test. t-test values on Weight test between anthropometric variables of badminton and handball players was significant and t-test value between fitness variables of badminton and handball players on Sit-up highlighted the significant. Keywords: Anthropometric, Fitness, Badminton, Handball I. INTRODUCTION Recognizing true talents for a particular sport is very complex process and requires good knowledge of the anthropometric and physiological characteristic that are relevant for top performance in the particular sport. Anthropometric characteristic of handball players have been suggested to be a biomarker in determining the athletic potential of an individual. In general, more successful teams are faller and have body fat than less successful teams compared the anthropometric profile of England handball player with Asian ones from different countries. The world of games and sports has crossed many milestones, as a result of different achievements in general and their application in the field of sport in particular. Scientific investigations into performance role attain excellence of performance in different sports. Now the sportsman have been able to give outstanding performance because of involvement of new scientifically substantiated training methods and means of execution of sports exercise such as sports techniques and tactics, improvement of sport grass, and equipment, as well as other components and condition of the system of sports training. -

BADMINTON RULES Objective: to Hit a Shuttlecock Across the Net to Land

BADMINTON RULES Objective: To hit a shuttlecock across the net to land in your opponent's court without having them return it using their own racket. If it is hit by your opponent then a rally occurs until the shuttle is either hit out of the designated area or lands on the court before being hit. In either case, the person who hit the shuttle outside of the designated boundary, or allowed the shuttle to land on their court has lost the rally and the other player receives a point (independent of who served). Each game goes to 21. The best player out of 3 sets to 21 is considered the winner. Singles One player on each side of the net ‘Skinny and long’ boundary lines When beginning each set, or when the player serving has a score of an even number, they will serve from the right service court. If the players score is odd, they will serve from the left. If the server wins the rally, they receive a point and then serve once again, switching to the opposite service court. If the receiver wins a rally, they receive a point, now having the chance to serve (from the appropriate service court) Other Rules to keep in mind: You must win each round by 2 points. If score is 20-20, play until winner wins by 2. If players are still tied at 29-29, the winner is decided by the first player to reach a score of 30. When serving, the shuttle must be served diagonally to their opponents court There are no second serves. -

Core PE Learning Journey

Core PE Learning Journey Key Stage 3 & 4 Year 7 Year Year 11 Year UnderstadingPRACTICAL andSKIILS Applying AND APPLICATION Scientific Skills Skills Team Tactics Work Strategies Techniques Competitive Football Cricket Cricket Leadership Athletics Badminton/Table Tennis Badminton/Table Tennis Trampolining Leadership Athletics Lifestyle Boys Boys Boys Boys Boys Choices Girls Girls Girls Girls Girls Football Netball Handball/Badminton Trampolining Rounder's Trampolining Trampolining Handball/Badminton Netball Football Athletics Athletics Cricket Netball Athletics Rounder's Athletics YEAR Trampolining Boys Boys 11 Girls Girls Football Athletics Rounder's Athletics Rounder's Leadership Football Badminton/Table Tennis Trampolining Badminton/Table Tennis Football Trampolining Leadership Athletics YEAR Boys Boys Boys 10 Girls Girls Girls Handball/Badminton Athletics Netball Trampolining Trampolining Cricket Handball/Badminton Netball Football Cricket Leadership Athletics Badminton/Table Tennis Rounder's Leadership Trampolining Badminton/Table Tennis Football Trampolining Boys Boys Boys Girls Girls Girls Athletics Football Trampolining Football Trampolining Football Rounder's Netball Netball Handball/Badminton Handball/Badminton YEAR Athletics Table Tennis Gymnastics/Dance Gym/Dance Cricket 9 Football Table Tennis Rugby Football Rugby Cricket Athletics YEAR 8 Boys Boys Boys Boys Boys 8 Girls Girls Girls Girls Girls Football Athletics Athletics Athletics Dance/Badminton Gymnastics Trampolining Handball Netball Athletics Rounder's Cricket Fitness/ Team Building Netball Rounder's Athletics Gymnastics/Dance Rugby Table Tennis Gym/Dance Rugby Football Table Tennis Football Rounder's Cricket YEAR Boys Boys Boys Boys Girls Girls Girls Girls 7 Athletics Football Rounder's Netball Dance/Badminton Trampolining Gymnastics Netball Handball Fitness/ Team Building Service • Prayer • Achieve • Respect .