Downloaded Free at Newvoices.Org.Au

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our New York Book Fair List

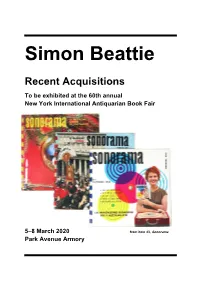

Simon Beattie Recent Acquisitions To be exhibited at the 60th annual New York International Antiquarian Book Fair 5–8 March 2020 from item 43, Sonorama Park Avenue Armory 01. ARCHENHOLZ, Johann Wilhelm von. A Picture of England: containing a Description of the Laws, Customs, and Manners of England … By M. d’Archenholz, formerly a Captain in the Service of the King of Prussia. Translated from the French … London: Printed for Edward Jeffery … 1789. 2 vols, 12mo (169 × 98 mm), pp. [4], iv, 210; [4], iv, 223, [1]; a very nice copy in contemporary mottled calf, smooth spines gilt in compartments, gilt-lettered morocco labels, a little worm damage to the upper joint of vol. I, but still handsome; engraved armorial bookplate of Sir Thomas Hesketh, Bart., of Rufford Hall, Lancashire; Easton Neston shelf label. $1300 First edition in English, with the sections on Italy omitted. ‘Archenholz did more than any other man to present a complete picture of England to Germans. His fifteen years of study and travel well qualified him as an observer of different peoples and their manners, and his views of England served Germany for a quarter of a century as their chief source of information’ (Cox). Cox III, 99; Morgan 75. LARGE PAPER COPY 02. [BERESFORD, Benjamin, and Joseph Charles MELLISH, translators]. Specimens of the German Lyric Poets: consisting of Translations in Verse, from the Works of Bürger, Goethe, Klopstock, Schiller, &c. Interspersed with Biographical Notices, and ornamented with Engravings on Wood, by the first Artists. London: Boosey and Sons … and Rodwell and Martin … 1822. 8vo (212 × 135 mm) in half-sheets, pp. -

Film Logline

Synopsis The Fifties, a Soviet space shuttle crashes in West Germany. The only passenger, a cosmonaut chimpanzee, spreads a deadly virus all over the country... Film Logline See: The Beginning of the End! Biography Javier Chillon (Madrid, 1977) Studied Audiovisual Communication at the Universidad Complutense of Madrid Southampton Institute Filmmaking MA. Works as an editor Credits Title Die Schneider Krankheit (The Schneider Disease) Year of Production 2008 Country of Origin Spain Language Spanish Genre Science Fiction Fake Documentary Running Time 10 minutes Shooting Format Super 8 Pre-selection Format DVD (Region 0, PAL & NTSC) Format for festival screening Digital Betacam (PAL & NTSC), Betacam SP (PAL & NTSC) and DVD (Region 0, PAL & NTSC) Ratio 4:3 Image Black and White Audio Stereo Contact Javier Chillon Phone number: 91 408 84 72 Mobile: 616 68 16 25 e-mail: [email protected] Web: www.javierchillon.com Producer and Director Javier Chillon Cinematographer Luis Fuentes Production Team María Ojeda Ángela Lecumberri Jaime Barnatan Production Design Ángel Boyano Nino Morante Production Design Assistants Diego Flores Tamara Prieto Special Effects Javier Chillon Senior Teresa Guerra Make-Up Isabel Auernheimer Hairdresser Mayte González Costume Design Ariadna Paniagua Animation Alicia Manero Script Javier Chillon Voice Over Writer Manuel Sánchez Translation Macarena Burgos Antonio Pérez Editing Javier Chillon Luis Fuentes Digital FX Majadero Films Labs Andec Filmtechnik Buscando Hormigas Music Cirilo Fernández Sound Carlos Jordá -

Liebman Expansions

MAY 2016—ISSUE 169 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM DAVE LIEBMAN EXPANSIONS CHICO NIK HOD LARS FREEMAN BÄRTSCH O’BRIEN GULLIN Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East MAY 2016—ISSUE 169 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : Chico Freeman 6 by terrell holmes [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : Nik Bärtsch 7 by andrey henkin General Inquiries: [email protected] On The Cover : Dave Liebman 8 by ken dryden Advertising: [email protected] Encore : Hod O’Brien by thomas conrad Editorial: 10 [email protected] Calendar: Lest We Forget : Lars Gullin 10 by clifford allen [email protected] VOXNews: LAbel Spotlight : Rudi Records by ken waxman [email protected] 11 Letters to the Editor: [email protected] VOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 In Memoriam 12 by andrey henkin International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or money order to the address above CD Reviews or email [email protected] 14 Staff Writers Miscellany David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, 37 Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Stuart Broomer, Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Event Calendar 38 Philip Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, Alex Henderson, Marcia Hillman, Terrell Holmes, Robert Iannapollo, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Ken Micallef, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Ken Waxman Tracing the history of jazz is putting pins in a map of the world. -

Latin America Spanish Only

Newswire.com LLC 5 Penn Plaza, 23rd Floor| New York, NY 10001 Telephone: 1 (800) 713-7278 | www.newswire.com Latin America Spanish Only Distribution to online destinations, including media and industry websites and databases, through proprietary and news agency networks (DyN and Notimex). In addition, the circuit features the following complimentary added-value services: • Posting to online services and portals. • Coverage on Newswire's media-only website and custom push email service, Newswire for Journalists, reaching 100,000 registered journalists from more than 170 countries and in more than 40 different languages. • Distribution of listed company news to financial professionals around the world via Thomson Reuters, Bloomberg and proprietary networks. Comprehensive newswire distribution to news media in 19 Central and South American countries: Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Domincan Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Puerto Rico, Uruguay and Venezuela. Translated and distributed in Spanish. Please note that this list is intended for general information purposes and may adjust from time to time without notice. 4,028 Points Country Media Point Media Type Argentina 0223.com.ar Online Argentina Acopiadores de Córdoba Online Argentina Agensur.info (Agencia de Noticias del Mercosur) Agencies Argentina AgriTotal.com Online Argentina Alfil Newspaper Argentina Amdia blog Blog Argentina ANRed (Agencia de Noticias Redacción) Agencies Argentina Argentina Ambiental -

Hiroshi Hamaya 1915 Born in Tokyo, Japan 1933 Joins Practical

Hiroshi Hamaya 1915 Born in Tokyo, Japan 1933 Joins Practical Aeronautical Research Institute (Nisui Jitsuyo Kouku Kenkyujo), starts working as an aeronautical photographer. The same year, works at Cyber Graphics Cooperation. 1937 Forms “Ginkobo” with his brother, Masao Tanaka. 1938 Forms “Youth Photography Press Study Group” (Seinen Shashin Houdou Kenkyukai) with Ken Domon and others. With Shuzo Takiguchi at the head, participates in “Avant-Garde Photography Association” (Zenei Shashin Kyokai). 1941 Joins photographer department of Toho-Sha. (Retires in 1943) Same year, interviews Japanese intellectuals as a temporary employee at the Organization of Asia Pacific News Agencies (Taiheiyo Tsushinsha). 1960 Signs contract with Magnum Photos, as a contributing photographer. 1999 Passed away SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2017 Record of Anger and Grief, Taka Ishii Gallery Photography / Film, Tokyo, Japan 2015 Hiroshi Hamaya Photographs 1930s – 1960s, The Niigata Prefectural Museum of Modern Art, Niigata, Japan, July 4 – Aug. 30; Traveled to: Setagaya Art Museum, Tokyo, Japan, Sept. 19 – Nov. 15; Tonami Art Museum, Toyama, Japan, Sept. 2 – Oct. 15, 2017. [Cat.] Hiroshi Hamaya Photographs 100th anniversary: Snow Land, Joetsu City History Museum, Niigata, Japan 2013 Japan's Modern Divide: The Photographs of Hiroshi Hamaya and Kansuke Yamamoto, J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, CA, USA [Cat.] 2012 Hiroshi Hamaya: “Children in Japan”, “Chi no Kao [Aspects of Nature]”, “American America”, Kawasaki City Museum, Kanagawa, Japan 2009 Shonan to Sakka II Botsugo -

SCT RDA Record Examples April 24, 2012

About the SCT RDA Record Examples April 24, 2012 The PCC SCT RDA Records Task Group collected and reviewed 138 records (8 authority records and 130 bibliographic records, including 3 that were non‐MARC). To the best of our knowledge, the records are consistent with revisions made to RDA that were included in the April 10, 2012 release of the RDA Toolkit. The task group received invaluable assistance from many individuals, whose contributions are acknowledged in the group’s Final Report. Needless to say, we are responsible for any and all errors in the records. To report errors in these records, please refer to contact information given in the last section of this introduction. The organization of the records reflects in part how and where they were collected. Please note that there is some overlap of categories. (e.g., Records for law resources include primarily textual monographs, but also a few online resources and a rare book). Policy decisions. The task group was faced with several thorny policy decisions, most notably: • Show a variety of practices acceptable under RDA, or follow the same RDA options and alternatives consistently? Adhere to LC practice in LCPSs? RDA allows a variety of practices: Bibliographic records can be entered at a core level, LC core level, or fuller level. Additionally, RDA often offers a choice of various other options and alternatives. LCPSs reflect LC practice, but there are no equivalent PCC policy statements. Relationship designators are optional, as are all note fields and most access points beyond the one for the primary work manifested. -

The Board of Trustees of the International Fund for Concerned Photography Is Drawn from Many Intellectual Disciplines. All Trust

the International fund for Concerned Photography inc. 275 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10016 The Board of Trustees of The International Fund for Concerned Photography is drawn from many intellectual disciplines. All trustees are involved in the visual perception of the world, working closely with us to identify talent and ideas, indicate the direc tion and quality of our various projects, and provide active support. Included among the Board and the Advisory Council are photographers, film-makers, educators, museum curators, art historians, psychologists, architects, writers, journalists, and business executives who share both a concern for man and his world and a commitment to the goals of the Fund. Board of Trustees - The International Fund for Concerned Photography Rosellina Bischof Burri Zurich: Founding Trustee Frank R. Donnelly New York: Child psychologist; social worker; author; Associate Director, Playschool Association; Founder, Studio Museum, Harlem Matthew Huxley Washington, D.C.: Chief, Standards Development Branch, National Institute of Mental Health; author Karl Katz New York: Chairman of Exhibitions and Loans, Metro politan Museum of Art Gy orgy Kepes Cambridge, Mass.: Professor of Visual Design, M.I.T.; painter; author Ellen Liman New York: Painter; author; collector William H. MacLeish Woods Hole, Mass.: Editor of Oceanus, the official publication of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Henry M. Margolis New York: Chairman of the Board of Trustees, ICP, industrialist; Director, American Committee of the Weizmann Institute of Science Mitchell Pallas Chicago: Chairman of the Board, Center for Photographic Arts Dr. Fritz Redi Massachusetts: Professor of Behavioral Sciences; author Nina Rosenwald New York: Photographer; board member, Young Concert Artists Society; member. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 055 500 FL 002 601 the Language Learner

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 055 500 FL 002 601 TITLE The Language Learner: Reaching His Heartand Mind. Proceedings sr the Second International Conference. INSTITUTION New York State Association ofForeign Language Teachers.; Ontario Modern LanguageTeachers' AssociatIon. PUB DATE 71 NOTE 298p.; Conference held in Toronto,Ontario, March 25-27, 1971 EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$9.87 DESCRIPTORS Articulation (Program); AudiolingualMethods; Basic Skills; Career Planning; *Conference Reports;English (Second Language); *Instructional ProgramDivisions; Language Laboratories; Latin; *LearningMotivation; Low Ability Students; *ModernLanguages; Relevance (Education); *Second Language Learning;Student Interests; Student Motivation; TeacherEducation; Textbook Preparation ABSTRACT More than 20 groups of commentaries andarticles which focus on the needs and interestsof the second-language learner are presented in this work. Thewide scope of the study ranges from curriculum planning to theoretical aspects ofsecond-language acquisition. Topics covered include: (1) textbook writing, (2) teacher education,(3) career longevity, (4) programarticulation, (5) trends in testing speaking skills, (6) writing and composition, (7) language laboratories,(8) French-Canadian civilization materials,(9) television and the classics, (10)Spanish and student attitudes, (11) relevance and Italianstudies, (12) German and the Nuffield materials, (13) Russian and "Dr.Zhivago," (14) teaching English as a second language, (15)extra-curricular activities, and (16) instructional materials for theless-able student. (RL) a a CONTENTS KEYNOTE ADDRESS: DR. WILGA RIVERS 1 - 11 HOW CAN STUDENTS BE INVOLVED IN PLANNING THE LANGUAGE CURRICULUM 12 - 24 TRIALS AND TRIBULATIONS OF A LANGUAGE TEXTBOOK WRITER 25 - 38 PREPARING FOREIGN LANGUAGE TEACHERS: NEW EMPHASIS IN THE 70'S 39 - 52 STAMINA AND THE LANGUAGE TEACHER: WAYS IN WHICH TO ACHIEVE LONGEVITY 53 - 64 A SEQUENTIAL LANGUAGE CURRICULUM IN HIGHER EDUCATION 65 - 81 NEW TRENDS IN TESTING THE SPEAKING SKILL IN ELEM AND SEC. -

An Unfinished Story: Gender Patterns in Media Employment

| An Unfinished Story: I10 I10 Gender Patterns In Media Employment e e Communication Communication Mass Mass on on Papers Papers and and Reports Reports UNESCO Publishing Reports and papers on mass communication Request for permission to reproduce the Reports in full or in part should be addressed to the UNESCO Publishing Office. The following reports and papers have been issued and are obtainable from National Distributors of UNESCO Publications or from the Sector for Communication, Information and Informatics, UNESCO, 7 place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP. These titles have been published in English and French. Titles marked with an asterisk are also published in Spanish, those marked ‘a’ in Arabic, ‘c’ in Chinese and ‘r’ in Russian. Number Number 50 Television and the social education of women, 1967 *81 External radio broadcasting and international 51 An African experiment in radio forums for rural understanding, 1977 development. Ghana, 1964/1965, 1968 *83 National communication policy councils, 1979 52 Book development in Asia. A report on the production *84 Mass media: the image, role and social condition of and distribution of books in the region, 1967 women, 1979 53 Communication satellites for education, science and *85 New values and principles of cross-cultural culture, 1967 communication, 1979 54 8mm film for adult audiences, 1968 86 Mass media. Codes of ethics and councils, 1980 55 Television for higher technical education of the 87 Communication in the community, 1980 employed. A first report on a pilot project in Poland, *88 Rural journalism in Africa, 1981 1969 *89 The SACI/EXTERN project in Brazil: an analytical 56 Book development in Africa. -

Tlifttutio9 Visconsin Madison

DOCOMENI"'RESUME ED,038 901 FL 001 723 BUTP\3p Vollmer, Joseph F.,Pnri Others 'valuation of the rffect of roreign Language in the 71ementary School Upon Achievement in +hP HigT1 School. rinal Report. TliFTTUTIO9 Visconsin Madison. Oureau of Pusiness Research and Service. ONS AGrmrY Office of. Fducation (DREW), Washington, D.C. PITH DATE Jul F2 C NTPACT nrC-sAr-016 N rr-! P8p. ED4PPICE FDPS Price 4F-$0.0 D7SCPTPTOPS Acalemic AcIlievement, Audiolingual Skills, Comparativeclnalysis, Comparative Stati'stics, Elementary Schools, *Fles Programs, Fles Teachers, Grammar Ttanslation,method, *High Schools, Language Development, *Language Instruction, Danguage Research, *Modern Languages., Program rffectivess, *Program evaluation, Research, Second Languages,' Statistical Data A ABSTRACT This study of two student groups enrolled in secondary school foreign language programs evaluateS comparative achievement covering ',a four-year sequence of study. The control gr,oup, results, reflecting previous foreign language elementary school (PIES) instruction, provide' strong contrasts favoring the continuation and further development of PLES programs. Experiment description, research'design, and conclusions arereported., Description of FLT'S`FLS'courses, foreign language personnel data, and a detailed statistical report are included. (RL) F U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH,EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION k, C, THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCEDEXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE Cor% POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS CO PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATINGIT. 141 STAVED DO NOTNECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY. I CI LiLi EVALUATION OF THE EFFECT OF FOREIGN LANGUAGE STUDY . IN THE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL UPON ACHIEVEMENT IN THE HIGH SCHOOL ;Final Report Contractor: Board of Education,; Borough of Somerville, New Jersey Project Directori AssiStant Project Director: Dr. -

Mla Selective List of Materials for Use By

REPORT RESUMES ED 020 686 FL 000 181 1LA SELECTIVE LIST OF MATERIALS FOR USE BY TEACHERS OF MODERN FOREIGN LANGUAGES IN ELEMENTARY AND SECONDARY SCHOOLS. BY- OLLMANN, MARY J., ED. MODERN LANGUAGE ASSN. OF AMERICA, NEW YORK, N.Y. PUB DATE 62 CONTRACT OEC-SAE-8342 EDRS PRICE MF.40.75 HC-$6.80 168P. DESCRIPTORS- *SECONDARY SCHOOLS, *LANGUAGE TEACHERS, *ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHIES, *MODERN LANGUAGES, *INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIALS, FLES, TEXTBOOK EVALUATION, INFORMATION SOURCES, LANGUAGE LEARNING LEVELS, ROMANCE LANGUAGES, EVALUATION CRITERIA, MATERIALS GROUPED ACCORDING TO LANGUAGE (FRENCH, GERMAN; ITALIAN, MODERN HEBREW, NORWEGIAN, POLISH, PORTUGUESE, RUSSIAN, SPANISH, SWEDISH) AND SUBJECT MATTER ARE FOUND IN THIS ANNOTATED SELECTIVE LIST. FOR ITEMS IN EACH SECTION, INFORMATION INCLUDES LIST PRICES, GRADE LEVELS, LANGUAGE PROFICIENCY LEVELS, AND CRITICAL EVALUATIONS. APPENDIXES INCLUDE SELECTIVE AND ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHIES FOR SIX CULTURES (FRENCH, GERMAN, HISPANIC, ITALIAN, LUSO-BRAZILIAN, AND RUSSIAN), CRITERIA FOR THE EVALUATION OF MATERIALS; AND SOURCES OF MATEnIALS. (AF) U.S. DEPARTMENT Of HEALTH. ELiVATION & WELFARE FRENCH OFFICE Of EDUCATION GERMAN ITALIAN THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR OR6ANIZATION ORIGINATIN5 IT.POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS MODERN HEBREW STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY. NORWEGIAN POLISH PORTUGUESE RUSSIAN SPANISH SWEDISH MLA selective list of materials for use by TEACHERS OF MODERN FOREIGN LANGUAGES IN ELEMENTARY AND SECONDARY SCHOOLS EDITED BY Mary J. 011mann Prepared and Published by The Modern Language Association of America Pursuant to a Contract with the U.S. Office of Education, Department of Health, Education, and Welfare 1962 This Selective List of Materials supersedes the Materials Est published by the Modern Language Association in 1959 "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL HAS 2EEN GRANTED BY 0.Mottaktinu TO ERIC AND ORGANIZATI S °PELTING UNDER AGREEMENTS WITP U.S. -

The Photographer's Legacy: Our Members Speak out About Their Work

The magazine of The Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Japan May 2016, Volume 48 No. 5, ¥400 The photographer’s legacy: Our members speak out about their work Vol. 48, Number 5 May 2016 contact the editors [email protected] Publisher FCCJ Editor Gregory Starr Art Director Andrew Pothecary www.forbiddencolour.com Editorial Assistants Naomichi Iwamura, Tyler Rothmar Photo Coordinator Akiko Miyake Publications committee members Gavin Blair, Freelance (Chair); Geoffrey Tudor, Orient Aviation; Monzurul Huq, Prothom Alo; Julian Ryall, Daily Telegraph; Patrick Zoll, Neue Zürcher Zeitung; Sonja Blaschke, Freelance; John R. Harris, Freelance FCCJ BOARD OF DIRECTORS Bob President Suvendrini Kakuchi, University World News, UK Kirschenbaum 1st Vice President Peter Langan, Freelance 2nd Vice President Imad Ajami, IRIS Media Secretary Mary Corbett, Cresner Media Treasurer Robert Whiting, Freelance HLADIK MARTIN p14 Directors at Large In this issue Masaaki Fukunaga, the Sanmarg Milton Isa, Associate Member Yuichi Otsuka, Associate Member James Simms, Forbes Contributor, Freelance The Front Page Ex-officio Lucy Birmingham From the President by Suvendrini Kakuchi 4 Kanji William Sposato, Freelance Collections: Kyushu earthquakes by the numbers 4 FCCJ COMMITTEE CHAIRS Associate Members Liaison Milton Isa From the archives by Charles Pomeroy 5 Compliance Kunio Hamada DeRoy Memorial Scholarship Masaaki Fukunaga Entertainment Sandra Mori, Suvendrini Kakuchi Exhibition Bruce Osborn Film Karen Severns Finance Robert Whiting Food & Beverage Robert Whiting Freedom