Principal Agent Approach to House Nominations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Ori Inal Document. SCHOOL- CHOICE

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 460 188 UD 034 633 AUTHOR Moffit, Robert E., Ed.; Garrett, Jennifer J., Ed.; Smith, Janice A., Ed. TITLE School Choice 2001: What's Happening in the States. INSTITUTION Heritage Foundation, Washington, DC. ISBN ISBN-0-89195-100-8 PUB DATE 2001-00-00 NOTE 275p.; For the 2000 report, see ED 440 193. Foreword by Howard Fuller. AVAILABLE FROM Heritage Foundation, 214 Massachusetts Avenue, N.E., Washington, DC 20002-4999 ($12.95). Tel: 800-544-4843 (Toll Free). For full text: http://www.heritage.org/schools/. PUB TYPE Books (010) Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Academic Achievement; Charter Schools; Educational Vouchers; Elementary Secondary Education; Private Schools; Public Schools; Scholarship Funds; *School Choice ABSTRACT This publication tracks U.S. school choice efforts, examining research on their results. It includes: current publicschool data on expenditures, schools, and teachers for 2000-01 from a report by the National Education Association; a link to the states'own report cards on how their schools are performing; current private school informationfrom a 2001 report by the National Center for Education Statistics; state rankingson the new Education Freedom Index by the Manhattan Institute in 2000; current National Assessment of Educational Progress test results releasedin 2001; and updates on legislative activity through mid-July 2001. Afterdiscussing ways to increase opportunities for children to succeed, researchon school choice, and public opinion, a set of maps and tables offera snapshot of choice in the states. The bulk of the book containsa state-by-state analysis that examines school choice status; K-12 public schools andstudents; K-12 public school teachers; K-12 public and private school studentacademic performance; background and developments; position of the governor/composition of the state legislature; and statecontacts. -

A Critical Assessment of the Political Doctrines of Michael Oakeshott

David Richard Hexter Thesis Title: A Critical Assessment of the Political Doctrines of Michael Oakeshott. Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. 1 Statement of Originality I, David Richard Hexter, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged and my contribution indicated. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the college has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. David R Hexter 12/01/2016 2 Abstract Author: David Hexter, PhD candidate Title of thesis: A Critical Assessment of the Political Doctrines of Michael Oakeshott Description The thesis consists of an Introduction, four Chapters and a Conclusion. In the Introduction some of the interpretations that have been offered of Oakeshott’s political writings are discussed. The key issue of interpretation is whether Oakeshott is best considered as a disinterested philosopher, as he claimed, or as promoting an ideology or doctrine, albeit elliptically. -

Election Calendars: Key Dates to Remember. 2020 Congressional Primary Calendar

Election Calendars: Key Dates to Remember. 2020 Congressional Primary Calendar January February March April May June July August September October November December Primaries Election Day Congressional Primaries Major-party Major-party State Date State Date filing deadline filing deadline Alabama Mar. 3 Nov. 8, 2019 South Carolina Jun. 9 Mar. 30 Arkansas Mar. 3 Nov. 11, 2019 Virginia Jun. 9 Mar. 26 California Mar. 3 Dec. 6, 2019 New York Jun. 23 Apr. 2 North Carolina Mar. 3 Dec. 20, 2019 Utah Jun. 23 Mar. 19 Texas Mar. 3 Dec. 9, 2019 Colorado Jun. 30 Mar. 17 Mississippi Mar. 10 Jan. 15 Oklahoma Jun. 30 Apr. 10 Ohio Mar. 17 Dec. 18, 2019 Arizona Aug. 4 Apr. 6 Illinois Mar. 17 Dec. 2, 2019 Kansas Aug. 4 Jun. 1 Maryland Apr. 28 Feb. 5 Michigan Aug. 4 Apr. 21 Pennsylvania Apr. 28 Feb. 18 Missouri Aug. 4 Mar. 31 Indiana May 5 Feb. 7 Washington Aug. 4 May 15 Nebraska May 12 Feb. 18 (incumbents); Tennessee Aug. 6 Apr. 2 Mar. 2 (non-incumbents) Hawaii Aug. 8 Jun. 2 West Virginia May 12 Jan. 25 Connecticut Aug. 11 Jun. 9 Georgia May 19 Mar. 6 Minnesota Aug. 11 Jun. 2 Idaho May 19 Mar. 13 Vermont Aug. 11 May 28 Kentucky May 19 Jan. 28 Wisconsin Aug. 11 Jun. 1 Oregon May 19 Mar. 10 Alaska Aug. 18 Jun. 1 Iowa Jun. 2 Mar. 13 Florida Aug. 18 Apr. 24 Montana Jun. 2 Mar. 9 Wyoming Aug. 18 May 29 New Jersey Jun. 2 Mar. 30 New Sept. 8 Jun. -

Ronald Reagan, Louisiana, and the 1980 Presidential Election Matthew Ad Vid Caillet Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2011 "Are you better off "; Ronald Reagan, Louisiana, and the 1980 Presidential election Matthew aD vid Caillet Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Caillet, Matthew David, ""Are you better off"; Ronald Reagan, Louisiana, and the 1980 Presidential election" (2011). LSU Master's Theses. 2956. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2956 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ―ARE YOU BETTER OFF‖; RONALD REAGAN, LOUISIANA, AND THE 1980 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History By Matthew David Caillet B.A. and B.S., Louisiana State University, 2009 May 2011 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to many people for the completion of this thesis. Particularly, I cannot express how thankful I am for the guidance and assistance I received from my major professor, Dr. David Culbert, in researching, drafting, and editing my thesis. I would also like to thank Dr. Wayne Parent and Dr. Alecia Long for having agreed to serve on my thesis committee and for their suggestions and input, as well. -

2017 Official General Election Results

STATE OF ALABAMA Canvass of Results for the Special General Election held on December 12, 2017 Pursuant to Chapter 12 of Title 17 of the Code of Alabama, 1975, we, the undersigned, hereby certify that the results of the Special General Election for the office of United States Senator and for proposed constitutional amendments held in Alabama on Tuesday, December 12, 2017, were opened and counted by us and that the results so tabulated are recorded on the following pages with an appendix, organized by county, recording the write-in votes cast as certified by each applicable county for the office of United States Senator. In Testimony Whereby, I have hereunto set my hand and affixed the Great and Principal Seal of the State of Alabama at the State Capitol, in the City of Montgomery, on this the 28th day of December,· the year 2017. Steve Marshall Attorney General John Merrill °\ Secretary of State Special General Election Results December 12, 2017 U.S. Senate Geneva Amendment Lamar, Amendment #1 Lamar, Amendment #2 (Act 2017-313) (Act 2017-334) (Act 2017-339) Doug Jones (D) Roy Moore (R) Write-In Yes No Yes No Yes No Total 673,896 651,972 22,852 3,290 3,146 2,116 1,052 843 2,388 Autauga 5,615 8,762 253 Baldwin 22,261 38,566 1,703 Barbour 3,716 2,702 41 Bibb 1,567 3,599 66 Blount 2,408 11,631 180 Bullock 2,715 656 7 Butler 2,915 2,758 41 Calhoun 12,331 15,238 429 Chambers 4,257 3,312 67 Cherokee 1,529 4,006 109 Chilton 2,306 7,563 132 Choctaw 2,277 1,949 17 Clarke 4,363 3,995 43 Clay 990 2,589 19 Cleburne 600 2,468 30 Coffee 3,730 8,063 -

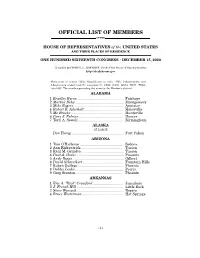

Official List of Members

OFFICIAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES of the UNITED STATES AND THEIR PLACES OF RESIDENCE ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS • DECEMBER 15, 2020 Compiled by CHERYL L. JOHNSON, Clerk of the House of Representatives http://clerk.house.gov Democrats in roman (233); Republicans in italic (195); Independents and Libertarians underlined (2); vacancies (5) CA08, CA50, GA14, NC11, TX04; total 435. The number preceding the name is the Member's district. ALABAMA 1 Bradley Byrne .............................................. Fairhope 2 Martha Roby ................................................ Montgomery 3 Mike Rogers ................................................. Anniston 4 Robert B. Aderholt ....................................... Haleyville 5 Mo Brooks .................................................... Huntsville 6 Gary J. Palmer ............................................ Hoover 7 Terri A. Sewell ............................................. Birmingham ALASKA AT LARGE Don Young .................................................... Fort Yukon ARIZONA 1 Tom O'Halleran ........................................... Sedona 2 Ann Kirkpatrick .......................................... Tucson 3 Raúl M. Grijalva .......................................... Tucson 4 Paul A. Gosar ............................................... Prescott 5 Andy Biggs ................................................... Gilbert 6 David Schweikert ........................................ Fountain Hills 7 Ruben Gallego ............................................ -

HR 4438 Don't Tax Higher Education

17 Elk Street 518-436-4781 www.cicu.org Albany, NY 12207 518-436-0417 fax www.nycolleges.org [email protected] Office of the President October 11, 2019 The Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Honorable Kevin McCarthy Speaker Minority Leader U.S. House of Representatives U.S. House of Representatives The Honorable Bobby Scott The Honorable Virginia Foxx Chairman Ranking Member Committee on Education and Labor Committee on Education and Labor U.S. House of Representatives U.S. House of Representatives The Honorable Brendan Boyle The Honorable Bradley Byrne Pennsylvania’s 2nd District Alabama’s 1st District U.S. House of Representatives U.S. House of Representatives Dear Speaker Pelosi, Minority Leader McCarthy, Chairman Scott and Ranking Member Foxx, Congressman Boyle, and Congressman Byrne: On behalf of the 100+ private, not-for-profit colleges in New York State, I write to you today in support of the H.R. 4438 Don’t Tax Higher Education Act, sponsored by Representatives Boyle and Byrne. This legislation would repeal the excise tax on investment income of private colleges and universities. Under current law, certain private colleges and universities are subject to a 1.4 percent excise tax on net investment income. This provision applies to private colleges and universities that have endowment assets of $500,000 per Full Time Equivalent (FTE) student. State colleges and universities are not subject to this provision even though many enjoy very strong endowments. H.R. 4438 would correct the ill-conceived decision to tax higher education that was made in 2017. Endowments are used prudently to support the higher education mission of an institution, and a tax on them invariably lessens what can be spent on students and on providing access to a high-quality education. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E2018 HON

E2018 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks September 26, 2008 servicemembers and veterans. To address friendship and dedication to the American peo- national model for over 600 programs in 50 this crisis, the bill establishes a Task Force on ple. States and the District of Columbia. the Prevention of Suicide by Members of the TERRY is a man who knows the meaning of Following his election to Congress, BUD Armed Forces to bring together experts from hard work. His father was a sharecropper and continued to be a leading voice for children. both within and outside of the military to as- worked on the railroad, instilling a strong work He authored the landmark law, the National sess current service suicide prevention pro- ethic with TERRY and his siblings at an early Children’s Advocacy Program Act, which pro- grams and policies and to examine the risk age. TERRY never forgot those lessons, and vided funds to expand and enhance the chil- factors that can lead to suicide. The Secretary served his country with honor as an Air Force dren’s advocacy program into new commu- of Defense is required to develop a plan to im- intelligence specialist in Europe before return- nities. He is also a member of the Advisory prove suicide prevention based upon the rec- ing home to Dothan, Alabama, in 1959. He Board for the National Center for Missing and ommendations of the task force. I urge Sec- joined the staff of the Dothan Eagle as a beat Exploited Children. retary Gates to convene this task force imme- reporter, and for 30 years climbed the cor- As a member of the House Appropriations diately and for the task force to complete its porate ladder with determination, working his Committee and the powerful Defense Appro- work as quickly as possible. -

Presidential Commission on the Supreme Court of the United States

Presidential Commission on the Supreme Court of the United States The Contemporary Debate over Supreme Court Reform: Origins and Perspectives Written Statement of Nikolas Bowie Assistant Professor of Law, Harvard Law School June 30, 2021 Co-Chair Rodriguez, Co-Chair Bauer, and members of the Commission, thank you for inviting me to testify. You have asked for my opinion about the causes of the current public debate over reforming the Supreme Court of the United States, the competing arguments for and against reform at this time, and how the commission should evaluate those arguments. The cause of the current public debate over reforming the Supreme Court is longstanding: Americans rightfully hold democracy as our highest political ideal, yet the Supreme Court is an antidemocratic institution. The primary source of concern is judicial review, or the power of the Court to decline to enforce a federal law when a majority of the justices disagree with a majority of Congress about the law’s constitutionality. I will focus on two arguments for reforming the Supreme Court, both of which object to the antidemocratic nature of judicial review. First, as a matter of historical practice, the Court has wielded an antidemocratic influence on American law, one that has undermined federal attempts to eliminate hierarchies of race, wealth, and status. Second, as a matter of political theory, the Court’s exercise of judicial review undermines the value that distinguishes democracy as an ideal form of government: its pursuit of political equality. Both arguments compete with counterarguments that judicial review is necessary to preserve the political equality of so-called discrete and insular minorities. -

Alabama Commission on Improving State Government

Office of the Governor - Robert Bentley Alabama Commission on Improving State Government Phase One Report 2011 Page | 1 Table of Contents Alabama Commission on Improving State Government Phase One Report Section Name Page Letter from the Chairman 2 Executive Order 4 3 - 4 Press Releases 5 - 10 Alabama Commission on Improving State Government Members 11 - 18 Executive Overview 19 - 21 Summary of Meetings and Methodology 22 Phase One: Recommendations for Executive Action and Executive Orders 23 - 46 Phase One: Recommendations Reviewed but Do Not Require Further Study 47 - 52 Phase Two: Recommendations Reviewed but Require Further Study 53 - 63 Conclusion 64 Appendix A: Executive Subcommittee Report 65 - 67 Appendix B: Memorandums and Letters 68 - 77 Appendix C: Consolidation Considerations 78 - 82 Appendix D: Website Submissions by Web Category 83 - 111 Appendix E: Website Submissions by Title 112 - 123 References 124 Page | 2 July 15, 2011 The Honorable Robert Bentley Governor of Alabama State Capitol Montgomery, Alabama Dear Governor Bentley: On behalf of the members appointed to the Commission, we are pleased to present to you this final report of the Alabama Commission on Improving State Government. The Commission was charged with the task of working with the Legislature and the Governor’s Policy Office to analyze and explore new ways to reduce government spending with minimal or no reduction to essential state services. From its inception, the focus of this Commission has been on the immediate implementation of recommendations, rather than merely establishing a set of recommendations to be placed in a report. In December 2008, the National Bureau of Economic Research announced that the U.S. -

Improving the Top-Two Primary for Congressional and State Races

Towards a More Perfect Election: Improving the Top-Two Primary for Congressional and State Races CHENWEI ZHANG* I. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................. 615 1I. B ACKGROUN D ................................................................................ 620 A. An Overview of the Law RegardingPrimaries ....................... 620 1. Types of Primaries............................................................ 620 2. Supreme Court JurisprudenceRegarding Political Partiesand Primaries....................................................... 622 B. The Evolution of the Top-Two Primary.................................. 624 1. A laska................................................................................ 62 5 2. L ouisiana .......................................................................... 625 3. California ......................................................................... 626 4. Washington ............................. ... 627 5. O regon ........................................... ................................... 630 I1. THE PROS AND CONS OF Top-Two PRIMARIES .............................. 630 A . P ros ......................................................................................... 63 1 1. ModeratingEffects ............................................................ 631 2. Increasing Voter Turnout................................................... 633 B . C ons ....................................................................................... 633 -

Documentation

HOUSE BILL NO. 1 ENROLLED TABLE OF CONTENTS SCHEDULE 01 - EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENT ..................................13 01-100 Executive Office ...........................................13 Administrative ..........................................13 Governor's Office of Coastal Activities .......................14 01-101 Office of Indian Affairs ......................................14 01-102 Office of the Inspector General ................................15 01-103 Mental Health Advocacy Service ..............................15 01-106 Louisiana Tax Commission ...................................16 01-107 Division of Administration ...................................17 Executive Administration ..................................17 Community Development Block Grant .......................17 Auxiliary Account .......................................18 01-109 Coastal Protection & Restoration Authority ......................19 01-111 Governor's Office of Homeland Security and Emergency Preparedness .........................................20 01-112 Department of Military Affairs ................................22 Military Affairs Program ..................................22 Education Program .......................................23 Auxiliary Account .......................................23 01-116 Louisiana Public Defender Board ..............................24 01-124 Louisiana Stadium and Exposition District .......................25 01-129 Louisiana Commission on Law Enforcement and the Administration of Criminal Justice ........................26