Matrix of Race

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

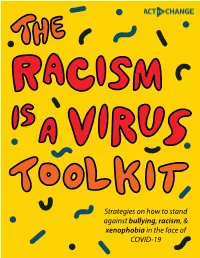

Racism Is a Virus Toolkit

Table of Contents About This Toolkit.............................................................................................................03 Know History, Know Racism: A Brief History of Anti-AANHPI Racism............04 Exclusion and Colonization of AANHPI People.............................................04 AANHPI Panethnicity.............................................................................................07 Racism Resurfaced: COVID-19 and the Rise of Xenophobia...............................08 Continued Trends....................................................................................................08 Testimonies...............................................................................................................09 What Should I Do If I’m a Victim of a Hate Crime?.........................................10 What Should I Do If I Witness a Hate Crime?..................................................12 Navigating Unsteady Waters: Confronting Racism with your Parents..............13 On Institutional and Internalized Anti-Blackness..........................................14 On Institutionalized Violence...............................................................................15 On Protests................................................................................................................15 General Advice for Explaning Anti-Blackness to Family.............................15 Further Resources...................................................................................................15 -

2019 Silent Auction List

September 22, 2019 ………………...... 10 am - 10:30 am S-1 2018 Broadway Flea Market & Grand Auction poster, signed by Ariana DeBose, Jay Armstrong Johnson, Chita Rivera and others S-2 True West opening night Playbill, signed by Paul Dano, Ethan Hawk and the company S-3 Jigsaw puzzle completed by Euan Morton backstage at Hamilton during performances, signed by Euan Morton S-4 "So Big/So Small" musical phrase from Dear Evan Hansen , handwritten and signed by Rachel Bay Jones, Benj Pasek and Justin Paul S-5 Mean Girls poster, signed by Erika Henningsen, Taylor Louderman, Ashley Park, Kate Rockwell, Barrett Wilbert Weed and the original company S-6 Williamstown Theatre Festival 1987 season poster, signed by Harry Groener, Christopher Reeve, Ann Reinking and others S-7 Love! Valour! Compassion! poster, signed by Stephen Bogardus, John Glover, John Benjamin Hickey, Nathan Lane, Joe Mantello, Terrence McNally and the company S-8 One-of-a-kind The Phantom of the Opera mask from the 30th anniversary celebration with the Council of Fashion Designers of America, designed by Christian Roth S-9 The Waverly Gallery Playbill, signed by Joan Allen, Michael Cera, Lucas Hedges, Elaine May and the company S-10 Pretty Woman poster, signed by Samantha Barks, Jason Danieley, Andy Karl, Orfeh and the company S-11 Rug used in the set of Aladdin , 103"x72" (1 of 3) Disney Theatricals requires the winner sign a release at checkout S-12 "Copacabana" musical phrase, handwritten and signed by Barry Manilow 10:30 am - 11 am S-13 2018 Red Bucket Follies poster and DVD, -

Black Girl Magic: the (Re)Imagining of Hermione Granger: an Analysis and Autoethnography

DePaul University Via Sapientiae College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences 6-2021 Black girl magic: the (re)imagining of Hermione Granger: an analysis and autoethnography Kandice Rose DePaul University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd Recommended Citation Rose, Kandice, "Black girl magic: the (re)imagining of Hermione Granger: an analysis and autoethnography" (2021). College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations. 306. https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd/306 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DePaul University Black Girl Magic: The (re)Imagining of Hermione Granger An Analysis and Autoethnography Kandice Rose Critical Ethnic Studies Graduate Candidate June 2021 1 INTRODUCTION I'd very much like to say that I've always loved to read, but that would be patently false. At the age of 6, when I was in the first grade, the grade where Americans generally learn to read, I absolutely hated it. My teacher, Mrs. Johnson, would call on students to stand up and read passages to the class. I would stare in awe as other kids would read their sentences flawlessly, even as butterflies rattled in my stomach, as I waited in dread for her to call on either myself or my twin sister. -

Islamic Psychology

Islamic Psychology Islamic Psychology or ilm an-nafs (science of the soul) is an important introductory textbook drawing on the latest evidence in the sub-disciplines of psychology to provide a balanced and comprehensive view of human nature, behaviour and experience. Its foundation to develop theories about human nature is based upon the writings of the Qur’an, Sunnah, Muslim scholars and contemporary research findings. Synthesising contemporary empirical psychology and Islamic psychology, this book is holistic in both nature and process and includes the physical, psychological, social and spiritual dimensions of human behaviour and experience. Through a broad and comprehensive scope, the book addresses three main areas: Context, perspectives and the clinical applications of applied psychology from an Islamic approach. This book is a core text on Islamic psychology for undergraduate and postgraduate students and those undertaking continuing professional development courses in Islamic psychology, psychotherapy and counselling. Beyond this, it is also a good supporting resource for teachers and lecturers in this field. Dr G. Hussein Rassool is Professor of Islamic Psychology, Consultant and Director for the Riphah Institute of Clinical and Professional Psychology/Centre for Islamic Psychology, Pakistan. He is accountable for the supervision and management of the four psychology departments, and has responsibility for scientific, educational and professional standards, and efficiency. He manages and coordinates the RICPP/Centre for Islamic Psychology programme of research and educational development in Islamic psychology, clinical interventions and service development, and liaises with the Head of the Departments of Psychology to assist in the integration of Islamic psychology and Islamic ethics in educational programmes and development of research initiatives and publication of research. -

The Invention of Asian Americans

The Invention of Asian Americans Robert S. Chang* Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 947 I. Race Is What Race Does ............................................................................................ 950 II. The Invention of the Asian Race ............................................................................ 952 III. The Invention of Asian Americans ....................................................................... 956 IV. Racial Triangulation, Affirmative Action, and the Political Project of Constructing Asian American Communities ............................................ 959 Conclusion ........................................................................................................................ 964 INTRODUCTION In Fisher v. University of Texas,1 the U.S. Supreme Court will revisit the legal status of affirmative action in higher education. Of the many amicus curiae (friend of the court) briefs filed, four might be described as “Asian American” briefs.2 * Copyright © 2013 Robert S. Chang, Professor of Law and Executive Director, Fred T. Korematsu Center for Law and Equality, Seattle University School of Law. I draw my title from THEODORE W. ALLEN, THE INVENTION OF THE WHITE RACE, VOL. 1: RACIAL OPPRESSION AND SOCIAL CONTROL (1994), and THEODORE W. ALLEN, THE INVENTION OF THE WHITE RACE, VOL. 2: THE ORIGIN OF RACIAL OPPRESSION IN ANGLO AMERICA (1997). I also note the similarity of my title to Neil Gotanda’s -

Uncovering Nodes in the Transnational Social Networks of Hispanic Workers

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Uncovering nodes in the transnational social networks of Hispanic workers James Powell Chaney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Chaney, James Powell, "Uncovering nodes in the transnational social networks of Hispanic workers" (2013). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3245. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3245 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. UNCOVERING NODES IN THE TRANSNATIONAL SOCIAL NETWORKS OF HISPANIC WORKERS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Geography & Anthropology by James Powell Chaney B.A., University of Tennessee, 2001 M.S., Western Kentucky University 2007 December 2013 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As I sat down to write the acknowledgment for this research, something ironic came to mind. I immediately realized that I too had to rely on my social network to complete this work. No one can achieve goals without the engagement and support of those to whom we are connected. As we strive to succeed in life, our family, friends and acquaintances influence us as well as lend a much needed hand. -

The Making and Unmaking of Ethnic Boundaries: a Multilevel Process Theory1

The Making and Unmaking of Ethnic Boundaries: A Multilevel Process Theory1 Andreas Wimmer University of California, Los Angeles Primordialist and constructivist authors have debated the nature of ethnicity “as such” and therefore failed to explain why its charac- teristics vary so dramatically across cases, displaying different de- grees of social closure, political salience, cultural distinctiveness, and historical stability. The author introduces a multilevel process theory to understand how these characteristics are generated and trans- formed over time. The theory assumes that ethnic boundaries are the outcome of the classificatory struggles and negotiations between actors situated in a social field. Three characteristics of a field—the institutional order, distribution of power, and political networks— determine which actors will adopt which strategy of ethnic boundary making. The author then discusses the conditions under which these negotiations will lead to a shared understanding of the location and meaning of boundaries. The nature of this consensus explains the particular characteristics of an ethnic boundary. A final section iden- tifies endogenous and exogenous mechanisms of change. TOWARD A COMPARATIVE SOCIOLOGY OF ETHNIC BOUNDARIES Beyond Constructivism The comparative study of ethnicity rests firmly on the ground established by Fredrik Barth (1969b) in his well-known introduction to a collection 1 Various versions of this article were presented at UCLA’s Department of Sociology, the Institute for Migration Research and Intercultural Studies of the University of Osnabru¨ ck, Harvard’s Center for European Studies, the Center for Comparative Re- search of Yale University, the Association for the Study of Ethnicity at the London School of Economics, the Center for Ethnicity and Citizenship of the University of Bristol, the Department of Political Science and International Relations of University College Dublin, and the Department of Sociology of the University of Go¨ttingen. -

0844 800 1110

www.rsc.org.uk 0844 800 1110 The RSC Ensemble is generously supported by THE GATSBY CHARITABLE FOUNDATION TICKETS and THE KOVNER FOUNDATION from Charles Aitken Joseph Arkley Adam Burton David Carr Brian Doherty Darrell D’Silva This is where the company’s work really begins to cook. By the time we return to Stratford in 2010 these actors will have been working together for over a year, and equipped to bring you a rich repertoire of eight Shakespeare productions as well as our new dramatisation of Morte D’Arthur, directed by Gregory Doran. As last year’s work grows and deepens with the investment of time, so new productions arrive from our exciting new Noma Dumezweni Dyfan Dwyfor Associate Directors David Farr and Rupert Goold, who open the Phillip Edgerley Christine Entwisle season with King Lear and Romeo and Juliet. Later, our new Artistic Associate Kathryn Hunter plays her first Shakespearean title role with the RSC in my production of Antony and Cleopatra, and we follow the success of our Young People’s The Comedy of Errors with a Hamlet conceived and directed by our award winning playwright in residence, Tarell Alvin McCraney. I hope that you will come and see our work as we continue to explore just how potent a long term community of wonderfully talented artists can be. Michael Boyd Artistic Director Geoffrey Freshwater James Gale Mariah Gale Gruffudd Glyn Paul Hamilton Greg Hicks James Howard Kathryn Hunter Kelly Hunter Ansu Kabia Tunji Kasim Richard Katz Debbie Korley John Mackay Forbes Masson Sandy Neilson Jonjo O’Neill Dharmesh Patel Peter Peverley Patrick Romer David Rubin Sophie Russell Oliver Ryan Simone Saunders Peter Shorey Clarence Smith Katy Stephens James Traherne Sam Troughton James Tucker Larrington Walker Kirsty Woodward Hannah Young Samantha Young TOPPLED BY PRIDE AND STRIPPED OF ALL STATUS, King Lear heads into the wilderness with a fool and a madman for company. -

Amaka Okafor

Amaka Okafor Theatre Title Role Director Producer Nora: A Doll's House Nora 3, Christine 2 Elizabeth Freestone The Young Vic The Son Sofia Michael Longhurst Duke Of York's The Son Sofia Michael Longhurst The Kiln Theatre Macbeth Lady Macduff Rufus Norris National Theatre I'm Not Running Meredith Ikeji Neil Armfield National Theatre Grimly Handsome Natalia/Nelly/Nally/Noplop Sam Pritchard & Chloe Lamford Royal Court Saint George and the Dragon Elsa Lyndsey Turner National Theatre Hamlet Guildenstern Robert Icke Almeida Theatre Peter Pan Nibs/Jane Sally Cookson National Theatre I See You DJ Mavovo Noma Dumezweni Royal Court Theatre Hamlet Palace Official Lyndsey Turner Sonia Freidman Productions Mermaid Mermaid Polly Teale Shared Experience Bird Leah Jane Fallowfield Tour Glasgow Girls Amal Cora Bissett Citizens Theatre Glasgow Girls Amal Cora Bissett NTS/Citizens Theatre Glasgow/Stratford East Dr Korczak's Example Stephanie Amy Leach Manchester Royal Exchange/Arcola The Bacchae The Bacchae John Tiffany & Steven Hoggett National Theatre of Scotland Branded Rox Matt Wilde Old Vic The Artists Partnership 21-22 Warwick Street, Soho, London W1B 5NE (020) 7439 1456 Old Vic 24 Hour Plays Sally Abigail Graham Old Vic Television Title Role Director Producer The Responder DI Debbie Barnes Fien Troch Dancing Ledge / BBC Grace DC Emma Jane Boutwood John Alexander ITV Des Emily Lewis Arnold ITV / New Pictures Vera 10 Laura Whitelock Paul Gay ITV The Split 2 Chloe Paula van Der Oest BBC The Artists Partnership 21-22 Warwick Street, Soho, London W1B 5NE (020) 7439 1456. -

Predicting Ethnic Boundaries Sun-Ki Chai

European Sociological Review VOLUME 21 NUMBER 4 SEPTEMBER 2005 375–391 375 DOI:10.1093/esr/jci026, available online at www.esr.oxfordjournals.org Online publication 22 July 2005 Predicting Ethnic Boundaries Sun-Ki Chai It is increasingly accepted within the social sciences that ethnic boundaries are not fixed, but contingent and socially constructed. As a result, predicting the location of ethnic boundaries across time and space has become a crucial but unresolved issue, with some scholars arguing that the study of ethnic boundaries and predictive social science are fun- damentally incompatible. This paper attempts to show otherwise, presenting perhaps the first general, predictive theory of ethnic boundary formation, one that combines a coher- ence-based model of identity with a rational choice model of action. It then tests the the- ory’s predictions, focusing in particular on the size of populations generated by alternative boundary criteria. Analysis is performed using multiple datasets containing information about ethnic groups around the world, as well as the countries in which they reside. Perhaps the best-known innovation in contemporary encompassing all ascriptively-based group boundaries, theories of ethnicity is the idea that ethnic boundaries including those based upon race, religion, language, are not predetermined by biology or custom, but malle- and/or region. Characteristics such as religion, language, able and responsive to changes in the surrounding social and region are viewed as ascriptive rather than cultural environment. Ethnicity is seen to be socially con- because they are typically defined for purposes of ethnic- structed, and the nature of this construction is seen to ity to refer not to the current practice or location of indi- vary from situation to situation.1 This in turn has linked viduals, but rather to their lineage, the customs of their to a more general concern with the contruction of social ancestors. -

De-Conflating Latinos/As' Race and Ethnicity

UCLA Chicana/o Latina/o Law Review Title Los Confundidos: De-Conflating Latinos/As' Race and Ethnicity Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9nx2r4pj Journal Chicana/o Latina/o Law Review, 19(1) ISSN 1061-8899 Author Sandrino-Glasser, Gloria Publication Date 1998 DOI 10.5070/C7191021085 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California LOS CONFUNDIDOS: DE-CONFLATING LATINOS/AS' RACE AND ETHNICITY GLORIA SANDRmNO-GLASSERt INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................71 I. LATINOS: A DEMOGRAPHIC PORTRAIT ..............................................75 A. Latinos: Dispelling the Legacy of Homogenization ....................75 B. Los Confundidos: Who are We? (Qui6n Somos?) ...................77 1. Mexican-Americans: The Native Sons and D aughters .......................................................................77 2. Mainland Puerto Ricans: The Undecided ..............................81 3. Cuban-Americans: Last to Come, Most to Gain .....................85 II. THE CONFLATION: AN OVERVIEW ..................................................90 A. The Conflation in Context ........................................................95 1. The Conflation: Parts of the W hole ..........................................102 2. The Conflation Institutionalized: The Sums of All Parts ...........103 B. The Conflation: Concepts and Definitions ...................................104 1. N ationality ..............................................................................104 -

Linda by Penelope Skinner and the Wasp by Morgan Lloyd Malcolm Performance Reviews

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 13 | 2016 Thomas Spence and his Legacy: Bicentennial Perspectives Linda by Penelope Skinner and The Wasp by Morgan Lloyd Malcolm Performance reviews William C. Boles Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/9420 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.9420 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference William C. Boles, “Linda by Penelope Skinner and The Wasp by Morgan Lloyd Malcolm ”, Miranda [Online], 13 | 2016, Online since 23 November 2016, connection on 16 February 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/miranda/9420 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.9420 This text was automatically generated on 16 February 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Linda by Penelope Skinner and The Wasp by Morgan Lloyd Malcolm 1 Linda by Penelope Skinner and The Wasp by Morgan Lloyd Malcolm Performance reviews William C. Boles Factual information about the shows 1 Play : Linda by Penelope Skinner Place : Royal Court Theatre Downstairs (London) Running time : November, 29th, 2015-January, 9th, 2016 Director : Michael Longhurst Set Designer : Es Devlin Costume Designer : Alex Lowde Lighting Designer : Lee Curran Composer and Sound Designer : Richard Hammarton Video Designer : Luke Halls Movement Director : Imogen Knight Cast : Imogen Byron, Karla Crome, Jaz Deol, NomaDumezweni, Amy Beth Hayes, Dominic Mafham,