Oberlin Abolitionism from 1839 to 1859

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RELIGIOSITY and REFORM in OBERLIN, OHIO, 1833-1859 Matthew Inh Tz Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 5-2012 PARADISE FOUND: RELIGIOSITY AND REFORM IN OBERLIN, OHIO, 1833-1859 Matthew inH tz Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hintz, Matthew, "PARADISE FOUND: RELIGIOSITY AND REFORM IN OBERLIN, OHIO, 1833-1859" (2012). All Theses. 1338. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1338 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PARADISE FOUND: RELIGIOSITY AND REFORM IN OBERLIN, OHIO, 1833-1859 A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of the Arts History by Matthew David Hintz May 2012 Accepted by: H. Roger Grant, Committee Chair C. Alan Grubb Orville V. Burton ABSTRACT Founded as a quasi-utopian society by New England evangelists, Oberlin became the central hub of extreme social reform in Ohio’s Western Reserve. Scholars have looked at Oberlin from political and cultural perspectives, but have placed little emphasis on religion. That is to say, although religion is a major highlight of secondary scholarship, few have placed the community appropriately in the dynamic of the East and West social reform movement. Historians have often ignored, or glossed over this important element and how it represented the divergence between traditional orthodoxy in New England and Middle-Atlantic states, and the new religious hybrids found in the West. -

Charles Finney's Sanctification Model in Theological Context

CHARLES FINNEY’S SANCTIFICATION MODEL IN THEOLOGICAL CONTEXT Gerald L. Priest, Ph.D. Charles G. Finney—colorful and controversial nineteenth century “father of modern evangelism.” Most responses to Finney fall into one of two categories—the highly critical and the highly complimentary.1 Unfavorable works usually attack Finney’s unorthodox doctrine and methods; the favorable defend him as a godly soul winner who is misunderstood or unjustly vilified by those who disagree with his “successful” methods.2 My contention is that a critical evaluation of Finney’s own writings will reveal that he is in substantial disagreement with the cardinal doctrines of Christianity, and that his revivalist methodology, when examined in that context, is a defective paradigm for evangelism and revival. I would also suggest that Finney’s teachings and methods have generally been harmful to evangelical Christianity. Fundamentalism was born out of intense opposition to theological liberalism, and so it would appear a mega-contradiction to even suggest that fundamentalists could ever be “taken in” by rationalism in any form. Yet, interestingly, George Marsden has suggested that one of the formative features of early fundamentalism was Scottish Common Sense philosophy, a moralistic rationalism which contributed to the evidentialist epistemology of early fundamentalist apologetics.3 One version of Common Sense, rooted in Princeton, did play a significant role in fundamentalism, as Ernest Sandeen and later Mark Noll sought to prove.4 But Finney’s “new 1Some works sympathetic to Finney include L. G. Parkhurst, Jr., Finney’s Theology: True to Scripture, True to Reason, True to Life (Edmon, OK: Revival Resources, 1990) and his article, “Charles Grandison Finney Preached For A Verdict,” Fundamentalist Journal 3 (June 1984), pp. -

Oberlin Historic Landmarks Booklet

Oberlin Oberlin Historic Landmarks Historic Landmarks 6th Edition 2018 A descriptive list of designated landmarks and a street guide to their locations Oberlin Historic Landmarks Oberlin Historic Preservation Commission Acknowledgments: Text: Jane Blodgett and Carol Ganzel Photographs for this edition: Dale Preston Sources: Oberlin Architecture: College and Town by Geoffrey Blodgett City-wide Building Inventory: www.oberlinheritage.org/researchlearn/inventory Published 2018 by the Historic Preservation Commission of the City of Oberlin Sixth edition; originally published 1997 Oberlin Historic Preservation Commission Maren McKee, Chair Michael McFarlin, Vice Chair James Young Donna VanRaaphorst Phyllis Yarber Hogan Kristin Peterson, Council Liaison Carrie Handy, Staff Liaison Saundra Phillips, Secretary to the Commission Introduction Each building and site listed in this booklet is an officially designated City of Oberlin Historic Landmark. The landmark designation means, according to city ordinance, that the building or site has particular historic or cultural sig- nificance, or is associated with people or events important to the history of Oberlin, Ohio, or reflects distinguishing characteristics of an architect, archi- tectural style, or building type. Many Oberlin landmarks meet more than one of these criteria. The landmark list is not all-inclusive: many Oberlin buildings that meet the criteria have not yet been designated landmarks. To consider a property for landmark designation, the Historic Preservation Commission needs an appli- cation from its owner with documentation of its date and proof that it meets at least one of the criteria. Some city landmarks are also listed on the National Register of Historic Plac- es, and three are National Historic Landmarks. These designations are indicat- ed in the text. -

The Second Raid on Harpers Ferry, July 29, 1899

THE SECOND RAID ON HARPERS FERRY, JULY 29, 1899: THE OTHER BODIES THAT LAY A'MOULDERING IN THEIR GRAVES Gordon L. Iseminger University of North Dakota he first raid on Harpers Ferry, launched by John Brown and twenty-one men on October 16, 1859, ended in failure. The sec- ond raid on Harpers Ferry, a signal success and the subject of this article, was carried out by three men on July 29, 1899.' Many people have heard of the first raid and are aware of its significance in our nation's history. Perhaps as many are familiar with the words and tune of "John Brown's Body," the song that became popular in the North shortly after Brown was hanged in 1859 and that memorialized him as a martyr for the abolitionist cause. Few people have heard about the second raid on Harpers Ferry. Nor do many know why the raid was carried out, and why it, too, reflects significantly on American history. Bordering Virginia, where Harpers Ferry was located, Pennsylvania and Maryland figured in both the first and second raids. The abolitionist movement was strong in Pennsylvania, and Brown had many supporters among its members. Once tend- ing to the Democratic Party because of the democratic nature of PENNSYLVANIA HISTORY: A JOURNAL OF MID-ATLANTIC STUDIES, VOL. 7 1, NO. 2, 2004. Copyright © 2004 The Pennsylvania Historical Association PENNSYLVANIA HISTORY the state's western and immigrant citizens, Pennsylvania slowly gravitated toward the Republican Party as antislavery sentiment became stronger, and the state voted the Lincoln ticket in i 86o. -

000000RG 37/3 SOUND RECORDINGS: CASSETTE TAPES 000000Oberlin College Archives

000000RG 37/3 SOUND RECORDINGS: CASSETTE TAPES 000000Oberlin College Archives Box Date Description Subject Tapes Accession # 1 1950 Ten Thousand Strong, Social Board Production (1994 copy) music 1 1 c. 1950 Ten Thousand Strong & I'll Be with You Where You Are (copy of RCA record) music 2 1 1955 The Gondoliers, Gilbert & Sullivan Players theater 1 1993/29 1 1956 Great Lakes Trio (Rinehart, Steller, Bailey) at Katskill Bay Studio, 8/31/56 music 1 1991/131 1 1958 Princess Ida, Gilbert & Sullivan Players musicals 1 1993/29 1 1958 e.e. cummings reading, Finney Chapel, 4/1958 poetry 1 1 1958 Carl Sandburg, Finney Chapel, 5/8/58 poetry 2 24 1959 Mead Swing Lectures, B.F. Skinner, "The Evolution of Cultural Patterns," 10/28/1959 speakers 1 2017/5 24 1959 Mead Swing Lectures, B.F. Skinner, "A Survival Ethics" speakers 1 2017/5 25 1971 Winter Term 1971, narrated by Doc O'Connor (slide presentation) winter term 1 1986/25 21 1972 Roger W. Sperry, "Lateral Specializations of Mental Functions in the Cerebral Hemispheres speakers 1 2017/5 of Man", 3/15/72 1 1972 Peter Seeger at Commencement (1994 copy) music 1 1 1976 F.X. Roellinger reading "The Tone of Time" by Henry James, 2/13/76 literature 1 1 1976 Library Skills series: Card Catalog library 1 1 1976 Library Skills series: Periodicals, 3/3/76 library 1 1 1976 Library Skills series: Government Documents, 4/8/76 library 1 1 1977 "John D. Lewis: Declaration of Independence and Jefferson" 1/1/1977 history 1 1 1977 Frances E. -

John Anderson Copeland, Jr

GO TO LIST OF PEOPLE INVOLVED IN HARPERS FERRY VARIOUS PERSONAGES INVOLVED IN THE FOMENTING OF RACE WAR (RATHER THAN CIVIL WAR) IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA HDT WHAT? INDEX RACE WAR NOT CIVIL WAR John Anderson Copeland, Jr. was trapped along with his uncle Lewis Sheridan Leary and John Henry Kagi in “Hall’s Rifle Works” at the Harpers Ferry armory. When the three men made a run for the Shenandoah River they were trapped in a crossfire, but after Kagi had been killed and Leary had been shot several times and placed under arrest, Copeland was able to surrender without having been wounded. He refused to speak during his trial and was hanged with too short a drop and thus strangled slowly. On December 29, when a crowd of 3,000 would attend his funeral in his hometown of Oberlin, Ohio, there would be no body to bury, for after his cadaver had been temporarily interred in Charles Town it had been dug up and was in service in the instruction of students at the medical college in Winchester, Virginia. A monument was erected by the citizens of Oberlin in honor of their three fallen free citizens of color, Copeland, Leary, and Shields Green (the 8-foot marble monument would be moved to Vine Street Park in 1971). Judge Parker stated in his story of the trials (St. Louis Globe Democrat, April 8, 1888) that Copeland had been “the prisoner who impressed me best. He was a free negro. He had been educated, and there was a dignity about him that I could not help liking. -

1. Will Learn How to Analyze Historical Narratives

History 308/708, RN314/614, TX849 Religious Thought in America Fall Term, 2018 MWF: 1:25-2:15 Jon H. Roberts Office Hours: Mon. 3-5, Tues. 9-10, Office: 226 Bay State Road, Room 406 and by appointment 617-353-2557 (O); 781-209-0982 (H) [email protected] Course Description: Few concepts have proved more difficult to define than religion, but most students of the subject would agree that religious traditions commonly include rituals and other practices, aesthetic and emotional experiences, and a body of ideas typically expressed as beliefs. This course focuses on those beliefs during the course of American history from the first English colonial settlement to the present and on their interaction with the broader currents of American culture. Theology is the term often used to describe the systematic expression of religious doctrine. It is clearly possible, however, to discuss religious beliefs outside the context of formal theology, and it is at least arguable that some of the most influential beliefs in American history have received their most vivid and forceful expressions beyond the purview of theological discourse. Accordingly, while much of our attention in this course will focus on the works of theologians and clergy--the religious “professionals”--we shall also deal with religious strategies that a widely disparate group of other thinkers (e.g., scientists, artists, and other influential lay people) have deployed in attempting to account for the nature of the cosmos, the structure of the social order, and the dynamics of human experience. Most of the people whom we’ll be studying were committed proponents of Christianity or Judaism, but the course lectures and readings will also occasionally move outside of those traditions to include others. -

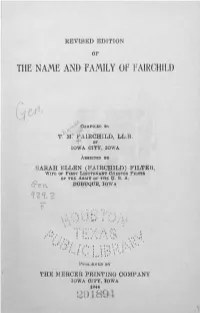

The Name and Family of Fairchild

REVISED EDITION OF THE NAME AND FAMILY OF FAIRCHILD tA «/-- .COMPILED BY TM.'FAIRCHILD, LL.B. OP ' IOWA CITY, IOWA ASSISTED BY SARAH ELLEN (FAIRCHILD) FILTER, WIPE OP FIRST LIEUTENANT CHESTER FILTER OP THE ARMY OP THE U. S. A. DUBUQUE, IOWA mz I * r • • * • • » < • • PUBLISHED BY THE MERCER PRINTING COMPANY IOWA CITY, IOWA 1944 201894 INDEX PART ONE Page Chapter I—The Name of Fairchild Was Derived From the Scotch Name of Fairbairn 5 Chapter II—Miscellaneous Information Regarding Mem bers of the Fairchild Family 10 Chapter III—The Heads of Families in the United States by the Name of Fairchild as Recorded by the First Census of the United States in 1790 50 Chapter IV—'Copy of the Fairchild Manuscript of the Media Research Bureau of Washington .... 54 Chapter V—Copy of the Orcutt Genealogy of the Ameri can Fairchilds for the First Four Generations After the Founding of Stratford and Settlement There in 1639 . 57 Chapter VI—The Second Generation of the American Fairchilds After Founding Stratford, Connecticut . 67 Chapter VII—The Third Generation of the American Fairchilds 71 Chapter VIII—The Fourth Generation of the American Fairchilds • 79 Chapter IX—The Extended Line of Samuel Fairchild, 3rd, and Mary (Curtiss) Fairchild, and the Fairchild Garden in Connecticut 86 Chapter X—The Lines of Descent of David Sturges Fair- child of Clinton, Iowa, and of Eli Wheeler Fairchild of Monticello, New York 95 Chapter XI—The Descendants of Moses Fairchild and Susanna (Bosworth) Fairchild, Early Settlers in the Berkshire Hills in Western Massachusetts, -

Oberlin and the Fight to End Slavery, 1833-1863

"Be not conformed to this world": Oberlin and the Fight to End Slavery, 1833-1863 by Joseph Brent Morris This thesis/dissertation document has been electronically approved by the following individuals: Baptist,Edward Eugene (Chairperson) Bensel,Richard F (Minor Member) Parmenter,Jon W (Minor Member) “BE NOT CONFORMED TO THIS WORLD”: OBERLIN AND THE FIGHT TO END SLAVERY, 1833-1863 A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Joseph Brent Morris August 2010 © 2010 Joseph Brent Morris “BE NOT CONFORMED TO THIS WORLD”: OBERLIN AND THE FIGHT TO END SLAVERY, 1833-1863 Joseph Brent Morris, Ph. D. Cornell University 2010 This dissertation examines the role of Oberlin (the northern Ohio town and its organically connected college of the same name) in the antislavery struggle. It traces the antislavery origins and development of this Western “hot-bed of abolitionism,” and establishes Oberlin—the community, faculty, students, and alumni—as comprising the core of the antislavery movement in the West and one of the most influential and successful groups of abolitionists in antebellum America. Within two years of its founding, Oberlin’s founders had created a teachers’ college and adopted nearly the entire student body of Lane Seminary, who had been dismissed for their advocacy of immediate abolition. Oberlin became the first institute of higher learning to admit men and women of all races. America's most famous revivalist (Charles Grandison Finney) was among its new faculty as were a host of outspoken proponents of immediate emancipation and social reform. -

© 2017 Christopher A. Howard ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

© 2017 Christopher A. Howard ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BLACK INSURGENCY: THE BLACK CONVENTION MOVEMENT IN THE ANTEBELLUM UNITED STATES, 1830 – 1865 A Dissertation Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Christopher A. Howard August 2017 BLACK INSURGENCY: THE BLACK CONVENTION MOVEMENT IN THE ANTEBELLUM UNITED STATES, 1830 – 1865 Christopher A. Howard Dissertation Approved: Accepted: _________________________________ _________________________________ Advisor Department Chair Dr. Walter Hixson Dr. Martin Wainwright _________________________________ _________________________________ Committee Member Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Dr. Elizabeth Mancke Dr. John C. Green _________________________________ _________________________________ Committee Member Executive Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Zachery Williams Dr. Chand Midha _________________________________ _________________________________ Committee Member Date Dr. Kevin Kern _________________________________ Committee Member Dr. Daniel Coffey ii ABSTRACT During the antebellum era, black activists organized themselves into insurgent networks, with the goal of achieving political and racial equality for all black inhabitants of the United States. The Negro Convention Movement, herein referred to as the Black Convention Movement, functioned on state and national levels, as the chief black insurgent network. As radical black rights groups continue to rise in the contemporary era, it is necessary to mine the historical origins that influence these bodies, and provide contexts for understanding their social critiques. This dissertation centers on the agency of the participants, and reveals a black insurgent network seeking its own narrative of liberation through tactics and rhetorical weapons. This study follows in the footing of Dr. Howard Holman Bell, who produced bodies of work detailing the antebellum Negro conventions published in the 1950s and 1960s. -

Book Reviews

Book Reviews Freedom and Grace: The Life of Asa Mahan, Edward H. Madden, and James E. Hamilton, Studies in Evangelicalism, No. 3, (Metuchen, NJ: The Scarecrow Press, 1982). 273 pp., $17.50. Since the appearance of Timothy Smith's Revivalism and Social Reform in 1957, historians of American religion have become increasingly aware of the central role Perfectionism played in the nineteenth century. Charles G. Finney, second President of Oberlin College, has been rightly recognized as the bridge via which the dominant stream of American religious experience crossed from the Puritan thought of the country's roots. In recent years, however, there has been a growing appreciation for the role which Oberlin's first President, Asa Mahan, played in that transformation. An accurate assessment of his impact has been hampered by the fact that, aside from his Memoirs published in 1882, no full-length treatment of his life has been offered. One hundred years later, Freedom and Grace has appeared to fill this gap. Mahan, born in New York State in 1799 to Presbyterian parents, was instilled with "Old Light" Calvinism during his youth. His conversion experience in young adulthood rendered this theology unconvincing. While at Andover Seminary in preparation for ministry, he accepted "New Light" Calvinism as the answer to his quest. Believing that nothing is either sinful or righteous unless it is a free act of the will, Mahan would, with Finney, go on to develop a concept of Christian Perfection within the Reformed Tradition that was very close to Wesley. They argued that since all sin is voluntary, it is inexcusable. -

Charles G. Finney and the Second Great Awakening Charles G

Reformation &;evival A Quarterly Journal for Church Leadership Volume 6, Number 1 • Winter 1997 Charles G. Finney and the. Second Great Awakening Whatever our experience or preference or our doctrinal BobPyke emphasis, if we dig over the ground long enough we shall find a revival somewhere to support our cause. Each week during the winter of 1834-35 a tall gaunt figure of Brian Edwards stern countenance mounted the pulpit of Chatham Street Chapel, New York, to deliver a lecture on "Revivals of Hence it is the solemn duty of each objector that he exam Religion." This young Presbyterian minister, whose steely ine his own heart, and the grounds of his indifference or blue eyes "swept his audience like searchlights," was Charles opposition to revivals. If they are the genuine work of God; Grandison Finney. The New York Evangelist printed his lec if they accord with the statements of the Bible; if they are tures as they were delivered. Shortly after the series con such results as he has a right to expect under the preach cluded they were published in April 1835 in book form .... ing of the gospel, he is bound, by all the love which he bears to his Saviour, and to the souls of men, to desire and The publication of his Lectures on Revival of Religion swept pray for their increase and extension. Finney into international prominence and extended his Henry C. Fish influence and teaching far beyond the bounds of the • English-speaking world .... His Lectures in whole and in part There is in the minds of most men a tendency to extremes; have been translated into many languages and published in and that tendency is never so likely to discover itself as in countless editions, and have become the raison d'etre of all a season of general excitement.