Tracking, School Mobility, and Educational Inequality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reform Strategy for Education in Ukraine

Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine REFORM STRATEGY FOR EDUCATION IN UKRAINE EDUCATIONAL POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS With the support of United Nations Development Programme, International Renaissance Foundation, Open Society Institute (Budapest) Kyiv – 2003 УДК 37.014.5: 37.014.3: 37.013.74 ББК 74.04 Reform Strategy for Education in Ukraine: Educational Policy Rec ommendations. – Kyiv: K.I.S., 2003. – 280 pages. A research on educational policy in Ukraine is presented in the book. The proposed publication is based upon the world approaches to definition and elaboration of options to solve educational sector problems. The authors ana lyze the modern tendencies in the 21century education development, de scribe possible alternatives, evaluate their prospects in terms of the imple mentation, and give recommendations. The main attention is attached to the following key areas of the educational reform: equal access to quality education, content of education, education quality monitoring, governance and financing. The book is for education policy makers, school managers, researchers, pedagogues, students and consultants. ISBN 9668039181 No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without prior permission of the MOES and UNDP/Ukraine. Cover photo by UN in Ukraine © Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine, 2003 © United Nations Development Programme, 2003 © "K.I.C.", design and layout, 2003 ISBN 9668039181 Contents Contents Foreword 5 Project Team and Partners 6 Introduction 9 COMPETENCIES AS A KEY TO EDUCATIONAL -

A Guide for the Placement of Students Presenting Foreign Transcripts

A Guide for the Placement of Students Presenting Foreign Transcripts Allen Altman Board Member, District 1 Marge Whaley Board Chairman, District 2 Cathi Martin Board Member, District 3 Kathryn Starkey Vice Chairman, District 4 Frank Parker Board Member, District 5 Heather Fiorentino Superintendent Sandra S. Ramos Assistant Superintendent for Curriculum and Instructional Services Olga Swinson Chief Finance Officer Renalia Smith DuBose, Esq. Assistant Superintendent for Administration James T. Davis Assistant Superintendent for High, Adult and Alternative Schools Tina Tiede Assistant Superintendent for Middle Schools Ruth B. Reilly Assistant Superintendent for Elementary Schools David Scanga, Ph.D. Executive Director for Elementary Programs Ray Gadd Assistant Superintendent for Support Services The District School Board of Pasco County ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The District School Board of Pasco County wishes to thank The School Board of Broward County, Florida Sayra Velez Hughes Executive Director Multicultural & ESOL Program Services Education Department for permitting the use and distribution of the document A Guide for the Placement of Foreign-Born Students. The guide was developed during the 2006-2007 school year and serves to assist schools in interpreting the transcripts presented by students coming from education systems outside of the United States. Jeff Morgenstein Supervisor for Curriculum and Instructional Services ESOL and World Languages INTRODUCTION The purpose of this guide is to provide teachers, administrators, and guidance counselors with a reference source for interpreting the transcripts presented by students who have been educated in a system outside of the United States. In order to appropriately place students in the grade and program of study commensurate with their prior educational experiences, a clear understanding of how other nations organize their school systems is essential. -

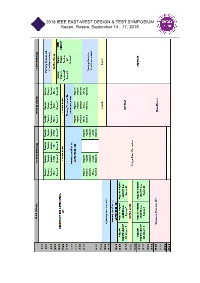

EWDTW'06 Conference Program Draft

2018 IEEE EAST-WEST DESIGN & TEST SYMPOSIUM Kazan, Russia, September 14 - 17, 2018 2018 IEEE EAST-WEST DESIGN & TEST SYMPOSIUM Kazan, Russia, September 14 - 17, 2018 FROM THE ORGANIZING COMMITTEE We have great pleasure to invite you to 16-th 2018 IEEE EAST-WEST DESIGN & TEST SYMPOSIUM (EWDTS-2018)! The purpose of the symposium is to coordinate and exchange experiences between leading scientific organizations and experts of the Eastern and Western Europe, as well as North America and other parts of the world, in the field of design, design automation and test of electronic circuits and systems. From the one side, an overview of the state-of-the-art and of the most important progress trends of the industrial design and test will be presented by leading researchers and practitioners. On the other side, an overview of recent achievements obtained by the scientists and technologists will be presented by the researchers and practitioners from countries in the region. We are happy that IEEE EWDTS is becoming a world-renown event, as we have seen the interest of Eastern and Western scientists in mutual collaboration. As a result of this collaboration we can see the penetration of new technologies in the Eastern Europe market and educational system. We would like to thank: Yervant Zorian, Sergey Mosin, Victor Djigan, Dmitry Efanov, Nikolay Prokopenko for taking an active role in organizing the conference technical program and finances, in international activity in the field of higher education and in support the preparation and operation of the symposium. The greatest appreciation to the official IEEE EWDTS – 2018 sponsors: IEEE, Computer Society, Test Technology Technical Council – TTTC. -

Intel ISEF 2013 Special Award Organizations Ceremony May 16, 2013 Phoenix, Arizona

Intel ISEF 2013 Special Award Organizations Ceremony May 16, 2013 Phoenix, Arizona Society for Science & the Public, in partnership with the Intel Foundation, announced the Special Award Organization winners of the Intel ISEF 2013. Student winners are ninth through twelfth graders who earned the right to compete at the Intel ISEF 2013 by winning a top prize at a local, regional, state or national science fair. Acoustical Society of America The Acoustical Society of America is the premier international scientific society in acoustics, dedicated to increasing and diffusing the knowledge of acoustics and its practical applications. First Award of $1,500; in addition, the student's school will be awarded $500 and the student's mentor will be awarded $250. PH002 Misbehaving Waves: The SurReal Thing Myles Withay Mitchell, 18, Limavady Grammar School, Limavady, Northern Ireland Second Award of $500; in addition, the student's school will be awarded $200, and the student's mentor will be awarded $100. EE037 An "EXTRA" Sense: Ultrasound Glove Assisting Spatial Orientation of the Visually Impaired Ivan Seleznov, 17, Specialized School No. 22, Mykolaiv, Ukraine Certificate of Honorable Mention CS044 Finding Best Speaker Position Using New Algorithms to Determine Acoustic Properties of a Room Akshat Boobna, 16, Amity International School, Saket, New Delhi, India PH308 "V-shaped Wave" Generated by a Moving Object: Analyses and Experiments on Capillary Gravity Waves Tomohiko Sato, 17, Hiroshima Prefectural Fuchu Senior High School, Fuchu-shi, Japan Takahiro Yomono, 18, Hiroshima Prefectural Fuchu Senior High School, Fuchu-shi, Japan The first place award winner's school will be awarded $500 and the student's mentor will be awarded $250. -

Russian Federation

International Qualifications Assessment Service (IQAS) Government of Alberta COUNTRY EDUCATION PROFILE The Former USSR and the Russian Federation 2 Prepared by: International Qualifications Assessment Service (IQAS) Contact Information: International Qualifications Assessment Service (IQAS) 9th Floor, 108 Street Building, 9942 108 Street, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T5K 2J5 Phone: 1 (780) 4272655 Fax: 1 (780) 4229734 © 2007 the Crown in right of the Province of Alberta, International Qualifications Assessment Service (IQAS) 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS........................................................................................................................ 4 LIST OF TABLES.................................................................................................................................. 7 LIST OF FIGURES.............................................................................................................................. 10 COUNTRY OVERVIEW..................................................................................................................... 11 HISTORICAL EDUCATION OVERVIEW........................................................................................ 17 EDUCATION IN THE FORMER USSR................................................................................................... 17 EDUCATION IN THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION AFTER 1991 .................................................................... 20 SCHOOL EDUCATION ..................................................................................................................... -

Russia 2019 Human Rights Report

RUSSIA 2019 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Russian Federation has a highly centralized, authoritarian political system dominated by President Vladimir Putin. The bicameral Federal Assembly consists of a directly elected lower house (State Duma) and an appointed upper house (Federation Council), both of which lack independence from the executive. The 2016 State Duma elections and the 2018 presidential election were marked by accusations of government interference and manipulation of the electoral process, including the exclusion of meaningful opposition candidates. The Ministry of Internal Affairs, the Federal Security Service (FSB), the Investigative Committee, the Office of the Prosecutor General, and the National Guard are responsible for law enforcement. The FSB is responsible for state security, counterintelligence, and counterterrorism as well as for fighting organized crime and corruption. The national police force, under the Ministry of Internal Affairs, is responsible for combating all crime. The National Guard assists the FSB Border Guard Service in securing borders, administers gun control, combats terrorism and organized crime, protects public order, and guards important state facilities. The National Guard also participates in armed defense of the country’s territory in coordination with Ministry of Defense forces. Except in rare cases, security forces generally reported to civilian authorities. National-level civilian authorities, however, had, at best, limited control over security forces in the Republic of Chechnya, which were accountable only to the head of Chechnya, Ramzan Kadyrov. The country’s occupation and purported annexation of Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula continued to affect the human rights situation there significantly and negatively. The Russian government continued to arm, train, lead, and fight alongside Russia-led forces in eastern Ukraine. -

Country School Name Level

List of Schools Eligible to Participate in TSL 2021 Debates Country School name Level Australia Manly Selective Campus NBSC Secondary Bangladesh Engineering University School and College Secondary Belarus School #71 of Minsk Primary School #1 named after M. M. Gruzhevsky Secondary School 151 Minsk Secondary Belgium European School Brussels 3 Secondary Bulgaria 128 SU 'Albert Einstein' Secondary PGT Asen Zlatarov Secondary Secondary School of Economics Georgi St. Rakovski Secondary Canada Island ConnectED K-12 School Secondary Paul Kane Secondary China Victoria Shanghai Academy Secondary Dominica Dominica Grammar School Secondary Egypt The International School of Elite Education Primary Alsadat Sec for Girls in Damro Secondary Bishbish Secondary common School Secondary El Gdeda Secondary School Secondary Ismailia STEM High School Secondary Obour STEM School Secondary Sharkia STEM School Secondary STEM Sharkia Secondary The International School of Elite Education Secondary Ghana Presbyterian Boys' Senior High School Secondary Tsito Senior High Technical School Secondary Greece Doukas School Secondary Honduras Alison Bixby Stone School Secondary India Aurum the Global School Primary & Secondary Dl. Dav Model School Primary & Secondary List of Schools Eligible to Participate in TSL 2021 Debates Ann Mary School Secondary Avasarshala Secondary Bharath Senior Secondary School Secondary Bhartiyam International School Secondary Bhavan Vidyalaya Secondary Hill Spring International School Secondary Individual Entry Secondary Jay Pratap Singh Public -

2021 Finalist Directory

2021 Finalist Directory April 29, 2021 ANIMAL SCIENCES ANIM001 Shrimply Clean: Effects of Mussels and Prawn on Water Quality https://projectboard.world/isef/project/51706 Trinity Skaggs, 11th; Wildwood High School, Wildwood, FL ANIM003 Investigation on High Twinning Rates in Cattle Using Sanger Sequencing https://projectboard.world/isef/project/51833 Lilly Figueroa, 10th; Mancos High School, Mancos, CO ANIM004 Utilization of Mechanically Simulated Kangaroo Care as a Novel Homeostatic Method to Treat Mice Carrying a Remutation of the Ppp1r13l Gene as a Model for Humans with Cardiomyopathy https://projectboard.world/isef/project/51789 Nathan Foo, 12th; West Shore Junior/Senior High School, Melbourne, FL ANIM005T Behavior Study and Development of Artificial Nest for Nurturing Assassin Bugs (Sycanus indagator Stal.) Beneficial in Biological Pest Control https://projectboard.world/isef/project/51803 Nonthaporn Srikha, 10th; Natthida Benjapiyaporn, 11th; Pattarapoom Tubtim, 12th; The Demonstration School of Khon Kaen University (Modindaeng), Muang Khonkaen, Khonkaen, Thailand ANIM006 The Survival of the Fairy: An In-Depth Survey into the Behavior and Life Cycle of the Sand Fairy Cicada, Year 3 https://projectboard.world/isef/project/51630 Antonio Rajaratnam, 12th; Redeemer Baptist School, North Parramatta, NSW, Australia ANIM007 Novel Geotaxic Data Show Botanical Therapeutics Slow Parkinson’s Disease in A53T and ParkinKO Models https://projectboard.world/isef/project/51887 Kristi Biswas, 10th; Paxon School for Advanced Studies, Jacksonville, -

Education for Democracy in Schools: Applying the Reference Framework of Competences for Democratic Culture

Education for Democracy in Schools: Applying the Reference Framework of Competences for Democratic Culture Online Conference of Senior Officials and Experts organised in the framework of the German Presidency of the Committee of Ministers 15-16 April 2021 LIST OF PARTICIPANTS NOMINATED SENIOR OFFICIALS ANDORRA Josep ARENY ACHÉ Directeur Département des Systèmes Educatifs, de l'Enseignement Supérieur et des Relations Internationales Ministère de l'Education et de l'Enseignement Supérieur d'Andorre Salvador SALA CARRASCO Chef de service des programmes scolaires Ministère de l'Education et de l'Enseignement Supérieur d'Andorre AUSTRIA Manfred WIRTITSCH Head of Unit Development and coordination of principal pedagogical reform processes Curricula development Citizenship education Federal Ministry of Education, Science and Research BELARUS Iryna KARZHOVA Head of the General Secondary Education Department Ministry of Education of the Republic of Belarus BELGIUM Natalie VERSTRAETE Head of Division Division of Horizontal Policies Flemish Department of Education and Training CZECH REPUBLIC Jaroslav FALTÝN Director of the Department of Basic Education and Youth Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports Kateřina KUBÁTOVÁ Department of International Relations Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports CYPRUS Andreas TSIAKKIROS Senior Education Planning Officer Primary Education Ministry of Education, Culture, Sport and Youth Chrystalla KOUKOUMA Secondary Education School Inspector Ministry of Education, Culture, Sport and Youth DENMARK Elsebeth ALLER Head -

Russian Federation Child Welfare Outcomes During the 1 990S

Report No. 24450-RU Russian Federation Child Welfare Outcomes During the 1990s: Public Disclosure Authorized The Case of Russia (In Two Volumes) Volume II: Main Report November, 2002 Human Development Sector Unit Europe and Central Asia Region Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Document of the World Bank ABBREVIATIONS RF - Russian Federation MLSD - Ministry of Labor and Social Development MOE - Ministry of Education MOH - Ministry of Health MOF - Ministry of Finance RLMS - Russia Longitudinal Monitoring Survey HH - household IMR - infant mortality rate WHO -World Health Organization MMR - matemal mortality rate PPE - preprimary education PE - primary education LSE - lower secondary education FSE - full secondary education TE - tertiary education. GDP - Gross Domestic Product ECA - Europe and Central Asia SWSCS - Social work and social care services NGOs - non-governmental organizations MHI - mandatory health insurance CIS - Commonwealth of Independent States CRC - The Convention on the Rights of the Child UN - United Nations PMPC - Psycho-Medico-Pedagogical Commissions MDRI - Mental Disability Rights International Vice President: Johannes F. Linn Country Director: Julian F. Schweitzer Sector Director: Annette Dixon Task Team Leader: Aleksandra Posarac Table of Contents Abbreviations ............................................................. 2 Preface ................................................... ..... 5 Acknowledgements ................................................... 6 Part -

Study of the Impact of Specialized Science High Schools

Study of the Impact of Selective SMT High Schools -1 Study of the Impact of Selective SMT High Schools: Reflections on Learners Gifted and Motivated in Science and Mathematics Rena F. Subotnik, American Psychological Association Robert H. Tai, University of Virginia John Almarode, James Madison University Rationale: A central challenge for the National Research Council committee exploring Highly Successful Schools or Programs for K-12 STEM Education was to determine the attributes of success for different populations found within U.S. schools. Our charge was to focus on appropriate outcomes for learners gifted and motivated in science and mathematics, most particularly those who enrolled in selective secondary schools of science, mathematics and technology (SMT). Although policy makers tend to rely on standardized measures of achievement to rate student response to special interventions and programs, scholars studying high achievers have found that measuring program effectiveness with standardized tests is complicated by ceiling effects. As a result, our project ascribes success to completion of STEM related university majors or to the application of SMT content and skills to other productive career goals. The goal of our project, in sum, is to assess the value added by selective SMT schools to developing and maintaining the STEM pipeline and the application of STEM knowledge and skills to non-STEM pursuits through the university years. Background: Selective science, mathematics and technology-focused high school schools offer the most intensive educational option for developing science talent at the secondary level. These environments typically bring together cohorts of highly able and motivated students with expert teachers, advanced curricula, technically sophisticated laboratory equipment and opportunities for apprenticeships with working scientists (Subotnik, Tai, Rickoff, & Almarode, Study of the Impact of Selective SMT High Schools -2 2010). -

Education in the USSR Research and Innovation

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 196 1241 Erv-013 146 AUTHOR Rosen, Seymour,M. TITLE Education in the U.S.S.R. Fesearch, andJnno"vation. INSTITUTION Office of Education (DHEW) ,Wa:shington,s`D.C. -FEPORT NO 0E-77-19130 PUB DATE 78 NOTD, 42p.: For related documents, see ED 109 929 and ED 128 255. AVAILABLE FROM Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402 (Stock No. 017-080-01815-2, $1.50). EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Academically Gifted; *Educational Innovation; Educational Objectives: Educational Planning: Educational Policy; *Educational Research: Elementary -AsSecondary Education; Foreign Countries; General Education; National Programs; Postsecondary Education; Research and Development Centers: Schools of Education; Second Language Programs; Technical 'Institutes; Vocational Education IDENTIFIERS 'Academy of Pedagogical Sciences (USSR): Ministry Higher Secondary Specialized Ed (USSR) Ministry of Education (USSFj; Scientific Research Inst Prcbs Higher Sch (USSR); *USSR ABSTFACT Following an introductory description of the etructure, administration, and general character of the Soviet system of education, this document discusses the status of educational .\resear'ch and innovation in the USSR. The system of .research is \outlined, and the organization and areas of inguiry:of the major research institutions, including the .divisions cf. the Academy of Pedagogical Science and the ScierAific-ReSearch Institute on Problems' of the Higher School,-are reviewed. Recent educational innovations reported in the document include creating special schools for the gifted in science and mathematics, combining vocational and general education, adding management tc the official list or higher education _Lspecialties,. revising the-syllabus of preschool education, providing schoolS specializing in foreign language instruction, and organizing preparatory departments- for higher education.