The Baltic American Partnership Fund (BAPF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Health Systems in Transition

61575 Latvia HiT_2_WEB.pdf 1 03/03/2020 09:55 Vol. 21 No. 4 2019 Vol. Health Systems in Transition Vol. 21 No. 4 2019 Health Systems in Transition: in Transition: Health Systems C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Latvia Latvia Health system review Daiga Behmane Alina Dudele Anita Villerusa Janis Misins The Observatory is a partnership, hosted by WHO/Europe, which includes other international organizations (the European Commission, the World Bank); national and regional governments (Austria, Belgium, Finland, Kristine Klavina Ireland, Norway, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the Veneto Region of Italy); other health system organizations (the French National Union of Health Insurance Funds (UNCAM), the Dzintars Mozgis Health Foundation); and academia (the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) and the Giada Scarpetti London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM)). The Observatory has a secretariat in Brussels and it has hubs in London at LSE and LSHTM) and at the Berlin University of Technology. HiTs are in-depth profiles of health systems and policies, produced using a standardized approach that allows comparison across countries. They provide facts, figures and analysis and highlight reform initiatives in progress. Print ISSN 1817-6119 Web ISSN 1817-6127 61575 Latvia HiT_2_WEB.pdf 2 03/03/2020 09:55 Giada Scarpetti (Editor), and Ewout van Ginneken (Series editor) were responsible for this HiT Editorial Board Series editors Reinhard Busse, Berlin University of Technology, Germany Josep Figueras, European -

Water Tourism D

5 POTTERY WORKSHOP OF VALDIS PAULINS CATERING SERVICES Hello, traveller! Address: Dumu Street 8, Kraslava, Kraslava municipality, Latvia 13 JAUNDOME ENVORONMENTAL EDUCATION CENTRE AND EXHIBITION HALL 21 MUSIC WORKSHOP “BALTHARMONIA” Mob.: +371 29128695 DINING HALL „ DAUGAVA” Address: Novomisli, Ezernieki rural territory, Dagda municipality, Latvia Address: "Bikava 2a", Gaigalava, Gaigalava rural territory, Rezekne municipality, Latvia CAFE “PIE ČERVONKAS PILS” This is a guide-book that will help you to experience an exciting trip along The Green Routes E-mail: [email protected] Address: Rigas Street 28, Kraslava, Mob.: +371 25960309 Phone: +371 28728790, + 371 26593441 Address: Cervonka-1, Vecsaliena rural territory, of the border areas of Latvia, Lithuania and Belarus. Routes leading to specially protected nature Website: http://www.visitkraslava.com/ Kraslavas municipality, Latvia E - mail: [email protected] E - mail: [email protected] Daugavpils municipality, Latvia areas under the state care are called “green” ones. These routes are “green” because providers of GPS: X:697648, Y:199786 / 55° 54' 10.30", 27° 9'42.27" Phone: +371 65622634, Mob.: +371 29112899 Website: www.visitdagda.com Website: http://www.baltharmonia.lv Mob.: +371 29726105 tourism service take care of accessibility of environment for people with disabilities. The workshop is around on the territory of the protected landscape Fax: +371 65622266 GPS: X:723253, Y:227872 / 56° 8' 36.72", 27° 35'88" GPS: X:687623, Y:291964 / 56° 44' 1.98", 27° 4'2.23" GPS: X: 673571, Y: 189832 / 55° 49’ 22.13’’, 26° 46’ 14.74’’ You are welcome at the places, where you will get acquainted with the values of the nature area „Augšdaugava”. -

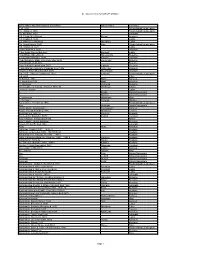

All Latvia Cemetery List-Final-By First Name#2

All Latvia Cemetery List by First Name Given Name and Grave Marker Information Family Name Cemetery ? d. 1904 Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava ? b. Itshak d. 1863 Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava ? b. Abraham 1900 Jekabpils ? B. Chaim Meir Potash Potash Kraslava ? B. Eliazar d. 5632 Ludza ? B. Haim Zev Shuvakov Shuvakov Ludza ? b. Itshak Katz d. 1850 Katz Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava ? B. Shalom d. 5634 Ludza ? bar Abraham d. 5662 Varaklani ? Bar David Shmuel Bombart Bombart Ludza ? bar Efraim Shmethovits Shmethovits Rezekne ? Bar Haim Kafman d. 5680 Kafman Varaklani ? bar Menahem Mane Zomerman died 5693 Zomerman Rezekne ? bar Menahem Mendel Rezekne ? bar Yehuda Lapinski died 5677 Lapinski Rezekne ? Bat Abraham Telts wife of Lipman Liver 1906 Telts Liver Kraslava ? bat ben Tzion Shvarbrand d. 5674 Shvarbrand Varaklani ? d. 1875 Pinchus Judelson d. 1923 Judelson Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava ? d. 5608 Pilten ?? Bloch d. 1931 Bloch Karsava ?? Nagli died 5679 Nagli Rezekne ?? Vechman Vechman Rezekne ??? daughter of Yehuda Hirshman 7870-30 Hirshman Saldus ?meret b. Eliazar Ludza A. Broido Dvinsk/Daugavpils A. Blostein Dvinsk/Daugavpils A. Hirschman Hirschman Rīga A. Perlman Perlman Windau Aaron Zev b. Yehiskiel d. 1910 Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava Aba Ostrinsky Dvinsk/Daugavpils Aba b. Moshe Skorobogat? Skorobogat? Karsava Aba b. Yehuda Hirshberg 1916 Hirshberg Tukums Aba Koblentz 1891-30 Koblentz Krustpils Aba Leib bar Ziskind d. 5678 Ziskind Varaklani Aba Yehuda b. Shrago died 1880 Riebini Aba Yehuda Leib bar Abraham Rezekne Abarihel?? bar Eli died 1866 Jekabpils Abay Abay Kraslava Abba bar Jehuda 1925? 1890-22 Krustpils Abba bar Jehuda died 1925 film#1890-23 Krustpils Abba Haim ben Yehuda Leib 1885 1886-1 Krustpils Abba Jehuda bar Mordehaj Hakohen 1899? 1890-9 hacohen Krustpils Abba Ravdin 1889-32 Ravdin Krustpils Abe bar Josef Kaitzner 1960 1883-1 Kaitzner Krustpils Abe bat Feivish Shpungin d. -

Estonia Economy Briefing: Wrapping the Year Up: in Search for a Productive Economic Reform E-MAP Foundation MTÜ

ISSN: 2560-1601 Vol. 35, No. 2 (EE) December 2020 Estonia economy briefing: Wrapping the year up: in search for a productive economic reform E-MAP Foundation MTÜ 1052 Budapest Petőfi Sándor utca 11. +36 1 5858 690 Kiadó: Kína-KKE Intézet Nonprofit Kft. [email protected] Szerkesztésért felelős személy: CHen Xin Kiadásért felelős személy: Huang Ping china-cee.eu 2017/01 Wrapping the year up: in search for a productive economic reform When your country’s economy is reasonably small but, to an extent, diverse, even a major crisis would not seem to be too problematic. Another story is when the pandemic substitutes ‘a major crisis’ – then there may be a dual problem of analysing the present and forecasting the future. In one of his main interviews (if not the main one), which was supposed to be wrapping the difficult year up, Estonian Prime Minister Jüri Ratas was into memorable metaphors when it would come to pure politics, but distinctly shy when a question was on economics1. During 2020, in political terms, the country was getting involved into discussing way more intra- political scandals than it would have been necessary to test the ‘health’ of a democracy. As for the process of running the economy, apart from borrowing more to survive the pandemic, the only major economic reform that the current governmental coalition managed to ‘squeeze’ through the ‘hurdles’ of the Riigikogu’s passing and the presidential approval was the so-called second pillar pension reform. The idea of the Government was to respond to a particular societal call that was, in a way, ‘inspired’ by Pro Patria and some other proponents of the prospective reform. -

Annual Report of the Chancello

Dear reader, In accordance with section 4 of the Chancellor of Justice Act, the Chancellor has to submit an annual report of his activities to the Riigikogu. The present overview of the conformity of legislation of general application with the Constitution and the laws covers the period from 1 June until 31 December 2004, and the outline of activities concerning the protection of fundamental rights and freedoms of persons, the period from 1 January until 31 December 2004. The overview contains summaries of the main cases that were settled as well as generalisations of the legal problems and difficulties, together with proposals on how to improve the protection of fundamental rights and freedoms and how to raise the quality of law making. The readers will also be able to familiarise themselves with the organisation of work in the Office of the Chancellor of Justice. According to the Constitution, the Chancellor of Justice is an independent constitutional institution. Such a status enables him to assess problems objectively and to protect people effectively from arbitrary measures of the state authority. One tool for fulfilling this task is the opportunity that the Chancellor of Justice has to submit to the Riigikogu his conclusions and considerations regarding shortcomings in legislation, in order to contribute to strengthening the principles of democracy and the rule of law. I am grateful to the members of the Riigikogu and its committees, in particular the Constitutional Committee, the Legal Affairs Committee and the Social Affairs Committee, for having been open to mutual, trustful and effective cooperation, which will hopefully continue just as fruitfully in the future. -

Competition Schedule

GAME Schedule saturday 3 to sunday 11 july 2021 RIGA & DAUGAVPILS Group A Group B Group C Group D SENEGAL (SEN) PUERTO RICO (PUR) ARGENTINA (ARG) TURKEY (TUR) CANADA (CAN) IRAN (IRI) FRANCE (FRA) MALI (MLI) LITHUANIA (LTU) SERBIA (SRB) KOREA (KOR) AUSTRALIA (AUS) JAPAN (JPN) LATVIA (LAT) SPAIN (ESP) USA (USA) Group Phase SEN - JPN CAN - LTU PUR - LAT IRI - SRB FRA - KOR ARG - ESP TUR - USA MLI - AUS sat (Group A) (Group A) (Group B) (Group B) (Group C) (Group C) (Group D) (Group D) Daugavpils Oly.Centre Daugavpils Oly.Centre Daugavpils Oly.Centre Daugavpils Oly.Centre 03 Riga Olympic Centre Riga Olympic Centre Riga Olympic Centre Riga Olympic Centre 76 - 71 80 - 71 79 - 75 67 - 88 117 - 48 69 - 68 54 - 83 67 - 97 JPN - CAN LTU - SEN LAT - IRI SRB - PUR KOR - ARG ESP - FRA AUS - TUR USA - MLI (Group A) (Group A) (Group B) (Group B) sun (Group C) (Group C) (Group D) (Group D) Daugavpils Oly.Centre Daugavpils Oly.Centre Daugavpils Oly.Centre Daugavpils Oly.Centre 04 Riga Olympic Centre Riga Olympic Centre Riga Olympic Centre Riga Olympic Centre 75 - 100 78 - 73 58 - 48 84 - 64 74 - 112 60 - 59 62 - 64 100 - 52 Monday 5 July - Rest day SEN - CAN LTU - JPN SRB - LAT PUR - IRI KOR - ESP ARG - FRA TUR - MLI AUS - USA (Group A) (Group A) (Group B) (Group B) tue (Group C) (Group C) (Group D) (Group D) Daugavpils Oly.Centre Daugavpils Oly.Centre Daugavpils Oly.Centre Daugavpils Oly.Centre 06 Riga Olympic Centre Riga Olympic Centre Riga Olympic Centre Riga Olympic Centre 56 - 85 95 - 63 71 - 70 68 - 81 48 - 99 52 - 89 58 - 54 66 - 87 FINAL PHASE -

Dental Disease in a 17Th–18Th Century German Community in Jelgava, Latvia

Papers on Anthropology XX, 2011, pp. 327–350 DENTAL DISEASE IN A 17TH–18TH CENTURY GERMAN COMMUNITY IN JELGAVA, LATVIA Elīna Pētersone-Gordina1, Guntis Gerhards2 1 Department of Archaeology, Durham University, South Road, Durham, United Kingdom 2 Institute of Latvian History, University of Latvia, Riga, Latvia ABSTRACT Aims: To determine the frequency and distribution of dental caries, periapical lesions, the periodontal disease, ante-mortem tooth loss and enamel hypoplasia in a high status, urban post-medieval population from the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia, and to compare these rates with those obtained from contemporary populations from urban and rural Latvian cemeteries. Materials: The sample analysed consisted of the dental remains of 108 individuals (39 male, 42 female and 27 non-adults) excavated from the Jelgava Holy Trinity Church cemetery in Latvia. A total of 1,233 teeth and 1,853 alveoli were examined. Results: The frequency of the observed conditions in this population was overall high but not anomalous for the post-medieval period in Latvia. The differences between the age and the sex groups when comparing the number of individuals affected were not significant. The number of teeth and/or alveoli affected by caries, the periodontal disease and the ante-mortem tooth loss proved to be significantly higher in females than males in both age groups and in total. The prevalence of enamel hypoplasia was high in both sex groups. Conclusions: The overall high rates of destructive dental diseases in this population were linked to the diet high in soft carbohydrates and refined sugars. The significant differences between the number of teeth and alveoli in male and female dentitions affected by caries, the periodontal disease and the ante-mortem tooth loss were linked to a differential diet, as well as high fertility demands and differences in the composition of male and female saliva. -

Proposal for FOSS4G Europe 2020 Valmiera Th 30 September 2019

Proposal for FOSS4G Europe 2020 Valmiera th 30 September 2019 OVERVIEW In cooperation with Valmiera City council and Valmiera Development Agency we propose the FOSS4G Europe 2020 conference to take place in Valmiera, Latvia. We would like to propose the FOSS4G Europe 2020 conference to take place in Valmiera as the international nor european FOSS4G events have not yet been to this North-Eastern part of Europe. Latvia is democratic republic for almost 30 years and part of the European Union for the past 15 years the conference would be set in an environment that the FOSS4GE event has not been in before. As with Latvia’s setting in the zigzag of history the guiding motto behind the conference would be to remember the past but look and live for the future. Valmiera is a town situated in the historic Vidzeme region on the banks of the Gauja river. About 100 km North-East from the Latvian capital Rīga, and 50 km from the Estonian Southern border. The place dates back to the 13th century; Valmiera was founded in 1283 with city rights granted in 1323. Valmiera was a site of the Livonian Order (an autonomous branch of the Teutonic Order) stronghold - Valmiera castle. To this day the castle’s ruins lie in the city centre. Most of the old buildings dating back to the 18th-19th century were destroyed in the fires during the last war. Nevertheless we would like to urge the participants to discover the city and its historic surroundings as an extracurricular activity to the conference: hiking the Gauja National Park, kayaking on the Gauja river, bobsleighing in Sigulda, and a visit to the Turaida castle. -

Madona, Varakļāni, MADONA Cesvaines, Ērgļu, Lubānas, Madonas, Varakļānu Novads

Cesvaine, Ērgļi, Lubāna, Madona, Varakļāni, MADONA Cesvaines, Ērgļu, Lubānas, Madonas, Varakļānu novads UZŅĒMUMI KARTES PAŠVALDĪBAS ETENS ETENS Ļ TNIECISKAIS BI TNIECISKAIS Ē P - VI Ī Mājaslapu izstrāde INFORMAT SEO risinājumi Mārketinga koncepti Sociālo tīklu profilu izveide nelieliem uzņēmumiem 2020/21 www.latvijastalrunis.lv 67770577 AKTUĀLAIS UN NOZĪMĪGAIS PORTĀLĀ ZIŅAS AFIŠA KATALOGS KARTE GALERIJAS SLUDINĀJUMI PAŠVALDĪBA Kur zvanīt steidzamos gadījumos?? 2 - 3 Uzziņas un pakalpojumi Pašvaldību informācija 4 - 15 Kartes, ielu saraksti, informācija 16 - 17 Uzņēmējdarbības vide 18 - 19 Alfabētiskais 20 - 28 nozaru saraksts Nozaru daļa 29 - 57 Firmu saraksts pēc to darbības sfēras Advokāti - Bankas 29 - 33 Būvuzraudzība… - Celtniecības… 34 - 35 Ceļu… - Daiļamatniecība 35 - 35 Dzīvnieku… - Ekonomikas… 37 - 37 Ēdināšanas… - Iepakojums… 37 - 39 Izglītība… - Jaunrades… 39 - 40 Juvelierizstrādājumi… - Kafija… 40 - 40 Ķīmiskā… - Labiekārtošana… 42 - 42 Lopkopība - Maize… 43 - 44 Mūzikas - Namu… 46 - 46 Notāri - Parfimērijas… 47 - 47 Putnkopība - Radio… 52 - 53 Rūpniecības… - Sabiedriskais… 53 - 53 Somas… - Tabakas… 54 - 54 Tūrisms… - Ugunsdzēsība… 55 - 55 Ūdensapgāde… - Valsts… 55 - 55 Viesnīcas… - Žalūzijas… 56 - 57 Firmas alfabētiskā secībā Mājaslapu izstrāde A - J 58 - 61 www.latvijastalrunis.lv Firmas alfabētiskā secībā 67770577 K - Z 61 - 68 Uzziņas un pakalpojumi KUR ZVANĪT STEIDZAMOS GADĪJUMOS? UGUNSDZĒSĪBA UN GLĀBŠANA 01, 112 POLICIJA 02, 110, 112 MEDICĪNISKĀ PALĪDZĪBA 03, 112, 113 Medicīniskā palīdzība Avārijas dienesti Madonas slimnīca -

Best Baltic Basketball League

BBBL – BEST BALTIC BASKETBALL LEAGUE BBBL is an international basketball tournament for boys & girls aged U10 to U16 (years of birth 2011-2005) BBBL is the biggest and fastest growing regular Youth basketball tournament in Europe • the tournament was founded in 2012 • since season 2019/2020 we have started also girls tournament and renamed league to BEST BALTIC BASKETBALL LEAGUE • season of 2019/2020, BBBL participates 306 teams from 13 countries ABOUT BBBL season 2019/2010 BBBL teams, season 2019/2020, by age groups 60 50 306 teams 40 13 countries 30 20 4300 players 10 0 boys boys boys boys boys boys boys girls U11 girls U12 girls U13 girls U14 U10 U11 U12 U13 U14 U15 U16 BBBL teams by countries, season 2019/2020 MOL UK DEN SWE POL GEO UKR BLR FIN LTU RUS EST LV 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 BBBL STAGE MAP STAGE LOCATIONS LATVIA – Riga, Ozolnieki, Valmiera, Cēsis, Sigulda, Madona, Tukums, Talsi, Ventspils ESTONIA – Tartu, Tallin, Kaarikuu, Viimsi, Saaremaa LITHUANIA – Vilnius, Mazeikiai, Siauliai BELARUS – Minsk RUSSIA – Moscow, Tula FINLAND - Nokia FINAL STAGES : Riga, Valmiera, Cesis, Jelgava, Tartu BBBL TOURNAMENT KEY & FUNNY FACTS season 2019/2020 till covid-19 lockdown • 1851 games / almost all live on YouTube channel • 4300 players / 13 countries • 132 stages / 25 different locations • some teams travel very far away to play in BBBL tournament Krasnoyarsk 5`070 km London 2`317 km number of teams per seasons Tbilisi 2`874 km 350 Odesa 1`519 km 300 250 • besides players and coaches BBBL 200 tournament attracts a lot of other guests 150 /sometimes team brings 40+ person delegation for the bbbl stage/ 100 50 0 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 BBBL TOURNAMENT KEY & FUNNY FACTS • BBBL it`s not just a games, it`s a basketball festival full of joy & positive emotions only youth basketball - Skills challenges tournament where every - 3-point shot contests game is provided with full - Coach challenges FIBA standard live statistics - Coach meetings etc. -

The Saeima (Parliament) Election

/pub/public/30067.html Legislation / The Saeima Election Law Unofficial translation Modified by amendments adopted till 14 July 2014 As in force on 19 July 2014 The Saeima has adopted and the President of State has proclaimed the following law: The Saeima Election Law Chapter I GENERAL PROVISIONS 1. Citizens of Latvia who have reached the age of 18 by election day have the right to vote. (As amended by the 6 February 2014 Law) 2.(Deleted by the 6 February 2014 Law). 3. A person has the right to vote in any constituency. 4. Any citizen of Latvia who has reached the age of 21 before election day may be elected to the Saeima unless one or more of the restrictions specified in Article 5 of this Law apply. 5. Persons are not to be included in the lists of candidates and are not eligible to be elected to the Saeima if they: 1) have been placed under statutory trusteeship by the court; 2) are serving a court sentence in a penitentiary; 3) have been convicted of an intentionally committed criminal offence except in cases when persons have been rehabilitated or their conviction has been expunged or vacated; 4) have committed a criminal offence set forth in the Criminal Law in a state of mental incapacity or a state of diminished mental capacity or who, after committing a criminal offence, have developed a mental disorder and thus are incapable of taking or controlling a conscious action and as a result have been subjected to compulsory medical measures, or whose cases have been dismissed without applying such compulsory medical measures; 5) belong -

Gradients of Latvian Magnetic Anomalies

Scientific Journal of Riga Technical University Sustainable Spatial Development 2011 __________________________________________________________________________________________________ Volume 2 Gradients of Latvian Magnetic Anomalies Vladimir Vertennikov, Riga Technical University Abstract. This article discusses one of the most important and vertical gradients. It is possible to determine those geophysical factors, which produces an impact on the gradients by calculations or measurements using special demographic processes and reflects the nature of variability in instruments – magnetic gradiometers. Instrumented gradient the anomalous magnetic field intensity in space. The article characterises the horizontal magnetic gradients, which vary measurements are predominantly utilised in local areas during within the wide range: from 10 to 2400 nT/km. It distinguishes prospecting and exploration for minerals. In regional magnetic scale and magnetic gradient areas. The article gives an investigations, to which concrete operations associated with ecodemographic evaluation of the territory of Latvia by the investigating the impact of geophysical factors on gradience of the anomalous magnetic field. demographic processes belong, horizontal gradients are the main factor; they are determined by calculations. Keywords: horizontal magnetic gradient, magnetic scale, magnetic gradient area, ecodemographic evaluation of territory by magnetic gradience. CHARACTERISATION OF HORIZONTAL MAGNETIC GRADIENTS The magnetic field is represented in the Latvian territory by a complex set of anomalies with different signs, intensity, size The gradient is an important parameter of anomalous and morphology. The transitions from one anomaly to another magnetic field. The discussion deals with the spatial intensity are expressed through changes in the field intensity and are variations. The thing is that the intensity of the anomalous either gradual, occurring step-by-step, or abrupt.