271 Chapters 11 and 111 Give Us More Backgrounds Tor the Period

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

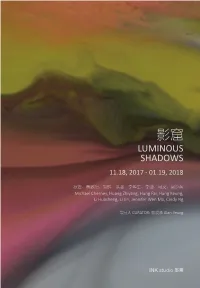

影窟 Luminous Shadows 11.18, 2017 - 01.19, 2018

影窟 LUMINOUS SHADOWS 11.18, 2017 - 01.19, 2018 秋麦、黄致阳、熊辉、洪强、李华生、李津、马文、吴少英 Michael Cherney, Huang Zhiyang, Hung Fai, Hung Keung, Li Huasheng, Li Jin, Jennifer Wen Ma, Cindy Ng 策展人 CURATOR: 杨浚承 Alan Yeung 影窟 LUMINOUS SHADOWS 11.18, 2017 - 01.19, 2018 秋麦、黄致阳、熊辉、洪强、李华生、李津、马文、吴少英 Michael Cherney, Huang Zhiyang, Hung Fai, Hung Keung, Li Huasheng, Li Jin, Jennifer Wen Ma, Cindy Ng 策展人 CURATOR: 杨浚承 Alan Yeung Contents 006 展览介绍 Introduction 006 杨浚承 Alan Yeung 006 作品 Works 010 006 秋麦 Michael Cherney 010 黄致阳 Huang Zhiyang 026 熊辉 Hung Fai 050 洪强 Hung Keung 076 李华生 Li Huasheng 084 李津 Li Jin 112 马文 Jennifer Wen Ma 150 吴少英 Cindy Ng 158 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any other information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from Ink Studio. © 2017 Ink Studio Artworks © 1981-2017 The Artists (Front Cover Image 封面图片 ) 吴少英 Cindy NG | Sea of Flowers 花海 (detail 局部 ) | P116 (Back Cover Image 封底图片 ) 李津 Li Jin | The Hungry Tigress 舍身饲虎 (detail 局部 ) | P162 6 7 INTRODUCTION Alan Yeung A painted rock bleeds as living flesh across sheets of paper. A quivering line In Jennifer Wen Ma’s (b. 1970, Beijing) installation, light and glass repeatedly gives form to the nuances of meditative experience. The veiled light of an coalesce into an illusionary landscape before dissolving in a reflective ink icon radiates through the near-instantaneous marks by a pilgrim’s hand. -

Contemporary China: a Book List

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY: Woodrow Wilson School, Politics Department, East Asian Studies Program CONTEMPORARY CHINA: A BOOK LIST by Lubna Malik and Lynn White Winter 2007-2008 Edition This list is available on the web at: http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinabib.pdf which can be viewed and printed with an Adobe Acrobat Reader. Variation of font sizes may cause pagination to differ slightly in the web and paper editions. No list of books can be totally up-to-date. Please surf to find further items. Also consult http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinawebs.doc for clicable URLs. This list of items in English has several purposes: --to help advise students' course essays, junior papers, policy workshops, and senior theses about contemporary China; --to supplement the required reading lists of courses on "Chinese Development" and "Chinese Politics," for which students may find books to review in this list; --to provide graduate students with a list that may suggest books for paper topics and may slightly help their study for exams in Chinese politics; a few of the compiler's favorite books are starred on the list, but not much should be made of this because such books may be old or the subjects may not meet present interests; --to supplement a bibliography of all Asian serials in the Princeton Libraries that was compiled long ago by Frances Chen and Maureen Donovan; many of these are now available on the web,e.g., from “J-Stor”; --to suggest to book selectors in the Princeton libraries items that are suitable for acquisition; to provide a computerized list on which researchers can search for keywords of interests; and to provide a resource that many teachers at various other universities have also used. -

Nations and Art: the Shaping of Art in Communist Regimes

NATIONS AND ART: THE SHAPING OF ART IN COMMUNIST REGIMES Lena Galperina Advisor: Patrick Thaddeus Jackson Fall 09 and Spring 10 General University Honors Galperina 1 Looking back at history, although art is not a necessity like water or food, it has always been an integral part in the development of all civilizations. So what part does it play in society and what is its impact on people? One way to look at art is to look at what guides its development and what are the results that follow. In the case of this paper, I am focusing specifically on how the arts are shaped by the political bodies that govern people, specifically focusing on Communist regimes. This is art of public nature and an integral part of all society, because it is created with the purpose of being seen by many. This of course is not something unique to the Communist regimes, or even their time period. Art has had public function throughout history, all one has to do is look at something like the Renaissance altar pieces, the drawings and carvings on the walls of Egyptian monuments or the murals commissioned in USA through the New Deal. In fact the idea of “art for art’s sake” only developed in the early 19 th century. This means that historically art has been used for a particular function, or to convey a specific idea to the viewers. This does not mean that before the 19 th century art was always done for some grand purpose, private commissions existed too of course; but artists mostly relied on patrons and the art that was available to the public was often commissioned for a purpose, and usually conveyed some sort of message. -

IFA-Annual-2018.Pdf

Your destination for the past, present, and future of art. Table of Contents 2 W e l c o m e f r o m t h e D i r e c t o r 4 M e s s a g e f r o m t h e C h a i r 7 T h e I n s t i t u t e | A B r i e f H i s t o r y 8 Institute F a c u l t y a n d F i e l d s o f S t u d y 14 Honorary F e l l o w s h i p 15 Distinguished A l u m n a 16 Institute S t a f f 1 9 I n M e m o r i a m 2 4 F a c u l t y Accomplishments 30 Spotlight o n F a c u l t y R e s e a r c h 4 2 S t u d e n t V o i c e s : A r t H i s t o r y 4 6 S t u d e n t V o i c e s : Conservation 50 Exhibitions a t t h e I n s t i t u t e 5 7 S t u d e n t Achievements 6 1 A l u m n i i n t h e F i e l d 6 8 S t u d y a t t h e I n s t i t u t e 73 Institute S u p p o r t e d Excavations 7 4 C o u r s e H i g h l i g h t s 82 Institute G r a d u a t e s 8 7 P u b l i c Programming 100 Support U s Art History and Archaeology The Conservation Center The James B. -

UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Abstract Art in 1980s Shanghai / Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/16g2v1dm Author Jung, Ha Yoon Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Abstract Art in 1980s Shanghai A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Art History, Theory, and Criticism by Ha Yoon Jung Committee in charge: Professor Kuiyi Shen, Chair Professor Norman Bryson Professor Todd Henry Professor Paul Pickowicz Professor Mariana Wardwell 2014 The Dissertation of Ha Yoon Jung is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically. ____________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2014 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ………………………………………………………………....……. iii Table of Contents ………………………………………………………….…...……. iv List of Illustrations …………………………………………………………………... v Vita ……………………………………………………………………….……….… vii Abstract ……………………………………………………….………………..……. xi Chapter 1 Introduction ……………………………………………………….……………….. 1 Chapter 2 Abstract -

The Traditionalist Painter Lu Yanshao (1909-1993) in the 1950S

COMMUNIST OR CONFUCIAN? THE TRADITIONALIST PAINTER LU YANSHAO (1909-1993) IN THE 1950S THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Yanfei YIN B.A. Graduate Program in History of Art The Ohio State University 2012 Master's Examination Committee: Professor Julia F. Andrews Advisor Professor Christopher A. Reed Copyright by Yanfei YIN 2012 Abstract The establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 triggered a deluge of artistic challenges for the Chinese ink painter. Lu Yanshao (陸儼少 1909-1993), an artist skilled in poetry, painting and calligraphy, had built his renown on landscape paintings following a traditionalist style. As of 1949, however, Lu began to make figure paintings that adhered to the guidelines established by the Communist Party. Dramatic social and political changes occurred in the 1950s under the new Communist regime. The Anti-Rightist Campaign, launched in 1957, targeted a large number of educated people, including many artists. Lu Yanshao was condemned as a Rightist and was forced to endure four years of continuous labor reform (laodong gaizao 勞動改造) in the countryside before finally ridding himself of the label of Rightist in 1961. Starting in 1957, Lu shifted his focus from making figure paintings for the country’s sake to his personal interest – creating landscape paintings. In 1959, the artist completed the first twenty five leaves of his famous Hundred-Leaf Album after Du Fu’s Poems. The surviving fourteen leaves combined painting, calligraphy and poetry, and are considered to be early paintings of Lu’s mature phase. -

Jerome Silbergeld

SILBERGELD.CV 1 JEROME SILBERGELD P.Y. and Kinmay W. Tang Professor of Chinese Art History Director, P. Y. and Kinmay W. Tang Center for East Asian Art Affiliate Professor, East Asian Studies Department Member, East Asian Studies Program Executive Committee, Committee for Film Studies Princeton University 105 McCormick Hall Princeton, New Jersey 08544 609-258-6249 FAX 609-258-0103 [email protected] Education B.A., Stanford University, 1966 (History, with Departmental Honors) M.A., Stanford University, 1967 (History) Stanford University, 1967-68 (Ph.D. Program in History) Princeton University, 1968-69 (Ph.D. Program in Chinese Art and Archaeology) M.A., University of Oregon, 1972 (Art History, with University Honors) Ph.D., Stanford University, 1974 (Art History, with Departmental Distinction) Dissertation: "Political Symbolism in the Landscape Painting and Poetry of Kung Hsien (ca. 1620-1689)" Faculty Appointments University of Oregon, Department of Art History, Visiting Assistant Professor, 1974-75 University of Washington, Art History Program, China Studies Affiliate (Jackson School of International Studies), Cinema Studies Faculty; Assistant Professor, 1975-81; Associate Professor, 1981-87; Professor, 1987-2001; Donald E. Petersen Professor of Arts, 2000-2001; Affiliate Professor of Art History, 2001- Harvard University, Department of Fine Arts, Visiting Professor, 1996 Princeton University, P.Y. and Kinmay W. Tang Professor of Chinese Art History, Director Tang Center for Chinese and Japanese Art, Affiliate Professor of East Asian -

PDF of Books on 20Th- and Early 21St-Century Visual Art and Design in China

Bibliography of Contemporary Art in China, Taiwan, and the Chinese Diaspora (includes titles on Maoist-era China) Compiled by Emily Rohrabaugh, Lisa Claypool August 9, 2006 (all publications date to 2006 and earlier) Note: titles without call numbers have not yet been processed. TITLE 1996 shuang nian zhan, Taiwan yi shu zhu ti xing = 1996 Taipei biennial, the quest for identity / zhu ban dan wei Taibei shi li mei shu guan PUBLISHER Taibei Shi : Tai-bei shi li mei shu guan, Min guo 85- [1996- CALL # N7349.8 .I234 1996 v.2 TITLE 2004 nian Shanghai shuang nian zhan: ying xiang sheng cun / Fang Zengxian, Xu Jiang zhu ban. PUBLISHER Shanghai Shi: Shanghai shu hua chu ban she, 2004. CALL # TR102.S43 2004 TITLE Abode of illusion [videorecording] : the life and art of Chang Dai-chien (1899-1983) / produced and directed by Carma Hinton and Richard Gordon [in association with the Long Bow Group] PUBLISHER Santa Monica, CA : Direct Cinema Limited, [1994] CALL # ND1045.C53 A2 1993, video AUTHOR Ai, Weiwei. TITLE Ai Weiwei : works, Beijing 1993-2003 / [Ai Weiwei ; editor, Charles Merewether]. PUBLISHER [Hong Kong] : Timezone 8, c2003. CALL # NX583.Z9 A37 2003 AUTHOR Andrews, Julia Frances. TITLE A century in crisis : modernity and tradition in the art of twentieth-century China / Julia F. Andrews and Kuiyi Shen ; with essays by Jonathan Spence ... [et al.] PUBLISHER New York : Guggenheim Museum : Distributed by Harry N. Abrams, c1998. CALL # N7345 .A53 1998. AUTHOR Andrews, Julia Frances. TITLE Painters and politics in the People's Republic of China, 1949- 1979 / Julia F. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Qianshen Bai [email protected]

CURRICULUM VITAE Qianshen Bai [email protected] EDUCATION 1996 Ph.D. in History of Art, Yale University 1993 M.Phil. in History of Art, Yale University 1992 M.A. in History of Art, Yale University 1990 M.A. in Political Science, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, New Jersey 1985-86 Graduate Program in Political Science, Peking University, Beijing, China 1982 Bachelor of Law, Peking University TEACHING AND WORKING EXPERIENCES 2019- Director of Zhejiang University Museum of Art and Archaeology 2019- Dean of School of Art and Archaeology, Zhejiang University 2019- Professor of art history at School of Art and Archaeology, Zhejiang University 2015- Professor of art history at The Art and Archaeology Research Center, Research Institute of Cultural Heritage, Zhejiang University 2004-15 Associate professor of Asian art history, Department of Art History, Boston University 2002 Visiting assistant professor, Department of History of Art and Architecture, Harvard University (Spring semester) 1997-04 Assistant professor of Asian art history, Department of Art History, Boston University 1996-97 Assistant professor of Asian art history, Department of Art, Western Michigan University 1995 Instructor of Asian art history, Department of Art, Western Michigan University 1994 Co-instructor for the graduate seminar “Methods and Resources for the Study of Premodern China,” Yale University 1994 Instructor for the Yale College Seminar “The History and Techniques of Chinese and Japanese Calligraphy,” Yale University 1992 Teaching assistant for “Introduction to the History of Art,” Yale University 1987-90 Visiting instructor of calligraphy, Department of East Asian Language and Literature, Rutgers University 1982-85 Instructor of the history of Chinese political institutions, Peking University AWARDS AND HONORS 2011-12 Fellowship offered by the National Endowment for the Humanities. -

Press Release Hong Kong | March 26 | 2016

PRESS RELEASE HONG KONG | MARCH 26 | 2016 Art Basel's fourth edition in Hong Kong: a record year at all levels This year’s Art Basel show in Hong Kong attracted over 70,000 visitors, among them directors, curators, trustees and patrons from over 100 leading international museums and institutions. The show, which closed today, Saturday, March 26, 2016, featured a new floorplan, spotlighting strong performances by galleries from Asia and the West. Confirming Art Basel’s standing as the leading international art fair in Asia, galleries across all sectors reported strong sales throughout the week. Despite recent doubts surrounding the robustness of the international art market, Art Basel proved that there continues to be strong demand when high-quality work from premier galleries worldwide is presented to an audience of highly engaged collectors and museum directors. The continuing expansion and sophistication of the collector base from Asia's many regions was widely noted by gallerists. This year’s edition of Art Basel in Hong Kong, whose Lead Partner is UBS, offered its visitors 239 galleries with exhibition spaces in 35 countries and territories. Over half of the galleries have exhibition spaces in Asia and the Asia-Pacific, signifying Art Basel’s commitment to representing the continent at its Hong Kong show. Consolidating Insights, the sector dedicated to galleries and artists from across Asia, on the third floor and rearranging the distribution of smaller and larger galleries across both halls created a more balanced floorplan that ensured visitors navigated the show more extensively. 28 galleries exhibited at Art Basel in Hong Kong this year for the first time, including 18 leading Western galleries, alongside nine key Asian galleries and Selma Feriani Gallery from Tunisia. -

Deconstructing Gao Minglu: Critical Reflections on Contemporaneity and Associated Exceptionalist Readings of Contemporary Chinese Art

Deconstructing Gao Minglu: critical reflections on contemporaneity and associated exceptionalist readings of contemporary Chinese art Paul Gladston Introduction The term ‘contemporary Chinese art’ is now used widely in Anglophone contexts to denote various forms of avant-garde, experimental and museum-based visual art produced as part of the liberalization of culture that has taken place within the People’s Republic of China (PRC) following the ending of the Cultural Revolution in 1976 and the subsequent confirmation of Deng Xiaoping’s programme of economic and social reforms at the XI Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party in December 1978. Since its inception during the late 1970s, contemporary Chinese art has been characterized by an often conspicuous combining of images, attitudes and techniques appropriated from western(ized) modernist and international postmodernist art with aspects of autochthonous Chinese cultural thought and practice. Within the context of an international art world still informed strongly by poststructuralist thinking and practice, contemporary Chinese art is consequently considered to be a localized variant of postmodernism whose hybridizing of differing cultural outlooks/modes of production has the potential to act as a locus for the critical deconstruction of supposedly authoritative meanings—not least, essentialist conceptualizations of national-cultural identity used to underpin colonialist-imperialist relations of dominance. In stark contrast, within mainland China there is a widely held and durable belief in the existence of an essential, spatially bounded, Chinese national-cultural identity as well as in the potential manifestation of that identity through indigenous cultural practices including those associated with contemporary Chinese art. It is important to note that the dominant, starkly exceptionalist view of culture within mainland China does not extend authoritatively to Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan. -

Jerome Silbergeld

SILBERGELD.CV 1 JEROME SILBERGELD P.Y. and Kinmay W. Tang Professor of Chinese Art History Director, P. Y. and Kinmay W. Tang Center for East Asian Art Affiliate Professor, East Asian Studies Department Member, East Asian Studies Program Executive Committee, Committee for Film Studies Princeton University 105 McCormick Hall Princeton, New Jersey 08544 609-258-6249 FAX 609-258-0103 [email protected] Education B.A., Stanford University, 1966 (History, with Departmental Honors) M.A., Stanford University, 1967 (History) Stanford University, 1967-68 (Ph.D. Program in History) Princeton University, 1968-69 (Ph.D. Program in Chinese Art and Archaeology) M.A., University of Oregon, 1972 (Art History, with University Honors) Ph.D., Stanford University, 1974 (Art History, with Departmental Distinction) Dissertation: "Political Symbolism in the Landscape Painting and Poetry of Kung Hsien (ca. 1620-1689)" Faculty Appointments University of Oregon, Department of Art History, Visiting Assistant Professor, 1974-75 University of Washington, Art History Program, China Studies Affiliate (Jackson School of International Studies), Cinema Studies Faculty; Assistant Professor, 1975-81; Associate Professor, 1981-87; Professor, 1987-2001; Donald E. Petersen Professor of Arts, 2000-2001; Affiliate Professor of Art History, 2001- Harvard University, Department of Fine Arts, Visiting Professor, 1996 Princeton University, P.Y. and Kinmay W. Tang Professor of Chinese Art History, Director Tang Center for Chinese and Japanese Art, Affiliate Professor of East Asian