The Evolution of a Consolidated Market for Neo-Traditional

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

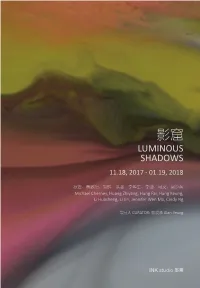

影窟 Luminous Shadows 11.18, 2017 - 01.19, 2018

影窟 LUMINOUS SHADOWS 11.18, 2017 - 01.19, 2018 秋麦、黄致阳、熊辉、洪强、李华生、李津、马文、吴少英 Michael Cherney, Huang Zhiyang, Hung Fai, Hung Keung, Li Huasheng, Li Jin, Jennifer Wen Ma, Cindy Ng 策展人 CURATOR: 杨浚承 Alan Yeung 影窟 LUMINOUS SHADOWS 11.18, 2017 - 01.19, 2018 秋麦、黄致阳、熊辉、洪强、李华生、李津、马文、吴少英 Michael Cherney, Huang Zhiyang, Hung Fai, Hung Keung, Li Huasheng, Li Jin, Jennifer Wen Ma, Cindy Ng 策展人 CURATOR: 杨浚承 Alan Yeung Contents 006 展览介绍 Introduction 006 杨浚承 Alan Yeung 006 作品 Works 010 006 秋麦 Michael Cherney 010 黄致阳 Huang Zhiyang 026 熊辉 Hung Fai 050 洪强 Hung Keung 076 李华生 Li Huasheng 084 李津 Li Jin 112 马文 Jennifer Wen Ma 150 吴少英 Cindy Ng 158 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any other information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from Ink Studio. © 2017 Ink Studio Artworks © 1981-2017 The Artists (Front Cover Image 封面图片 ) 吴少英 Cindy NG | Sea of Flowers 花海 (detail 局部 ) | P116 (Back Cover Image 封底图片 ) 李津 Li Jin | The Hungry Tigress 舍身饲虎 (detail 局部 ) | P162 6 7 INTRODUCTION Alan Yeung A painted rock bleeds as living flesh across sheets of paper. A quivering line In Jennifer Wen Ma’s (b. 1970, Beijing) installation, light and glass repeatedly gives form to the nuances of meditative experience. The veiled light of an coalesce into an illusionary landscape before dissolving in a reflective ink icon radiates through the near-instantaneous marks by a pilgrim’s hand. -

Contemporary China: a Book List

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY: Woodrow Wilson School, Politics Department, East Asian Studies Program CONTEMPORARY CHINA: A BOOK LIST by Lubna Malik and Lynn White Winter 2007-2008 Edition This list is available on the web at: http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinabib.pdf which can be viewed and printed with an Adobe Acrobat Reader. Variation of font sizes may cause pagination to differ slightly in the web and paper editions. No list of books can be totally up-to-date. Please surf to find further items. Also consult http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinawebs.doc for clicable URLs. This list of items in English has several purposes: --to help advise students' course essays, junior papers, policy workshops, and senior theses about contemporary China; --to supplement the required reading lists of courses on "Chinese Development" and "Chinese Politics," for which students may find books to review in this list; --to provide graduate students with a list that may suggest books for paper topics and may slightly help their study for exams in Chinese politics; a few of the compiler's favorite books are starred on the list, but not much should be made of this because such books may be old or the subjects may not meet present interests; --to supplement a bibliography of all Asian serials in the Princeton Libraries that was compiled long ago by Frances Chen and Maureen Donovan; many of these are now available on the web,e.g., from “J-Stor”; --to suggest to book selectors in the Princeton libraries items that are suitable for acquisition; to provide a computerized list on which researchers can search for keywords of interests; and to provide a resource that many teachers at various other universities have also used. -

Nations and Art: the Shaping of Art in Communist Regimes

NATIONS AND ART: THE SHAPING OF ART IN COMMUNIST REGIMES Lena Galperina Advisor: Patrick Thaddeus Jackson Fall 09 and Spring 10 General University Honors Galperina 1 Looking back at history, although art is not a necessity like water or food, it has always been an integral part in the development of all civilizations. So what part does it play in society and what is its impact on people? One way to look at art is to look at what guides its development and what are the results that follow. In the case of this paper, I am focusing specifically on how the arts are shaped by the political bodies that govern people, specifically focusing on Communist regimes. This is art of public nature and an integral part of all society, because it is created with the purpose of being seen by many. This of course is not something unique to the Communist regimes, or even their time period. Art has had public function throughout history, all one has to do is look at something like the Renaissance altar pieces, the drawings and carvings on the walls of Egyptian monuments or the murals commissioned in USA through the New Deal. In fact the idea of “art for art’s sake” only developed in the early 19 th century. This means that historically art has been used for a particular function, or to convey a specific idea to the viewers. This does not mean that before the 19 th century art was always done for some grand purpose, private commissions existed too of course; but artists mostly relied on patrons and the art that was available to the public was often commissioned for a purpose, and usually conveyed some sort of message. -

Environmental, Social and Governance Report 2020 SHAPING CITIES and HOMES with RESPONSIBILITY and SINCERITY

Environmental, Social and Governance Report 2020 SHAPING CITIES AND HOMES WITH RESPONSIBILITY AND SINCERITY START CONTENTS ABOUT THE REPORT 4 MESSAGE FROM THE BOARD 6 ABOUT LOGAN GROUP 8 BRAVELY FIGHT AGAINST THE PANDEMIC 11 BUSINESS PRINCIPLES OF SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT 17 EMPLOYEE CARE AND GROWTH 31 URBAN RENEWAL AND HARMONIZATION BETWEEN HUMAN HABITATION AND NATURE 44 ENVIRONMENT PROTECTION AND HARMONY 59 COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT AND PUBLIC WELFARE 71 STATISTICS SUMMARY 80 INDEX OF REPORTING INDICATORS 84 START 4 LOGAN GROUP COMPANY LIMITED ABOUT THE REPORT Logan Group Company Limited (the “Company”, together with its subsidiaries, “Logan”, the “Group” and “We”, “Us”) is a leading integrated town services provider in China who supports the national ABOUT THE REPORT THE ABOUT strategy in building an ecological civilization in Chinese society. The Group has spared no effort to fulfill corporate social responsibility in the past 25 years with a view to carving out the future and kindling hope. We are pleased to present the 5th Environmental, Social and Governance (“ESG”) Report (the “Report”) of Logan Group to illustrate our progress and achievements in sustainable development throughout 2020 and share our journey towards a more sustainable future with you. REPORTING SCOPE This Report covers the ESG performance of the Group from 1 January 2020 to 31 December 2020 (the “Reporting Period”, or the “Year”). The Board has determined to report our core real estate business in Mainland China based on the revenue significance and geographical presence of our principal businesses. In order to better demonstrate the Group’s commitments and achievements in sustainable development, the reporting scope for the Year will continue to cover our businesses such as real estate development, construction and fitting-out, land development, property leasing and related administrative work. -

IFA-Annual-2018.Pdf

Your destination for the past, present, and future of art. Table of Contents 2 W e l c o m e f r o m t h e D i r e c t o r 4 M e s s a g e f r o m t h e C h a i r 7 T h e I n s t i t u t e | A B r i e f H i s t o r y 8 Institute F a c u l t y a n d F i e l d s o f S t u d y 14 Honorary F e l l o w s h i p 15 Distinguished A l u m n a 16 Institute S t a f f 1 9 I n M e m o r i a m 2 4 F a c u l t y Accomplishments 30 Spotlight o n F a c u l t y R e s e a r c h 4 2 S t u d e n t V o i c e s : A r t H i s t o r y 4 6 S t u d e n t V o i c e s : Conservation 50 Exhibitions a t t h e I n s t i t u t e 5 7 S t u d e n t Achievements 6 1 A l u m n i i n t h e F i e l d 6 8 S t u d y a t t h e I n s t i t u t e 73 Institute S u p p o r t e d Excavations 7 4 C o u r s e H i g h l i g h t s 82 Institute G r a d u a t e s 8 7 P u b l i c Programming 100 Support U s Art History and Archaeology The Conservation Center The James B. -

UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Abstract Art in 1980s Shanghai / Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/16g2v1dm Author Jung, Ha Yoon Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Abstract Art in 1980s Shanghai A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Art History, Theory, and Criticism by Ha Yoon Jung Committee in charge: Professor Kuiyi Shen, Chair Professor Norman Bryson Professor Todd Henry Professor Paul Pickowicz Professor Mariana Wardwell 2014 The Dissertation of Ha Yoon Jung is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically. ____________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2014 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ………………………………………………………………....……. iii Table of Contents ………………………………………………………….…...……. iv List of Illustrations …………………………………………………………………... v Vita ……………………………………………………………………….……….… vii Abstract ……………………………………………………….………………..……. xi Chapter 1 Introduction ……………………………………………………….……………….. 1 Chapter 2 Abstract -

Seeing and Transcending Tradition in Chen Shuren's Guilin Landscape

Seeing and Transcending Tradition in Chen Shuren’s Guilin Landscape Album by Meining Wang A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History of Art, Design and Visual Culture Department of Art and Design University of Alberta ©Meining Wang, 2019 Abstract In 1931, the Chinese Lingnan school painter and modern Chinese politician Chen Shuren 陈树人 (1884-1948) went on a political retreat trip to Guilin, Guangxi China. During his trip in Guilin, Chen Shuren did a series of paintings and sketches based on the real scenic site of Guilin. In 1932, Chen’s paintings on Guilin were published into a painting album named Guilin shanshui xieshengji 桂林山水写生集 (The Charms of Kwei-Lin) by the Shanghai Heping Publishing House. By discussing how Chen Shuren’s album related with the past Chinese painting and cultural tradition in the modern context, I interpret it as a phenomenon that unified various Chinese painting concepts in modern Chinese history. I argue that by connecting the landscape of Guilin with a past Chinese cultural tradition and foreshowing a modern aesthetic taste, Chen Shuren merged Guilin into the 20th century Chinese cultural landscape. ii Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been completed without enormous help and encouragement from various aspects. I am grateful to Professor Walter Davis, for always patiently instructing me and being an excellent academic model for me. Not only in the academic sense, his passion and preciseness in art history also taught me knowledge about life. I am also very thankful for Professor Betsy Boone’s instruction, her intellectual approach always inspired me to move in new directions when my research was stuck. -

The Traditionalist Painter Lu Yanshao (1909-1993) in the 1950S

COMMUNIST OR CONFUCIAN? THE TRADITIONALIST PAINTER LU YANSHAO (1909-1993) IN THE 1950S THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Yanfei YIN B.A. Graduate Program in History of Art The Ohio State University 2012 Master's Examination Committee: Professor Julia F. Andrews Advisor Professor Christopher A. Reed Copyright by Yanfei YIN 2012 Abstract The establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 triggered a deluge of artistic challenges for the Chinese ink painter. Lu Yanshao (陸儼少 1909-1993), an artist skilled in poetry, painting and calligraphy, had built his renown on landscape paintings following a traditionalist style. As of 1949, however, Lu began to make figure paintings that adhered to the guidelines established by the Communist Party. Dramatic social and political changes occurred in the 1950s under the new Communist regime. The Anti-Rightist Campaign, launched in 1957, targeted a large number of educated people, including many artists. Lu Yanshao was condemned as a Rightist and was forced to endure four years of continuous labor reform (laodong gaizao 勞動改造) in the countryside before finally ridding himself of the label of Rightist in 1961. Starting in 1957, Lu shifted his focus from making figure paintings for the country’s sake to his personal interest – creating landscape paintings. In 1959, the artist completed the first twenty five leaves of his famous Hundred-Leaf Album after Du Fu’s Poems. The surviving fourteen leaves combined painting, calligraphy and poetry, and are considered to be early paintings of Lu’s mature phase. -

A Study of Paintings of Beautiful Woman by Selected Guangdong Artists in the Early Twentieth Century

ASIAN ART ESSAY PRIZE 2013 A Study of Paintings of Beautiful Woman by Selected Guangdong Artists in the Early Twentieth Century Leung Ge Yau (Candy) 2000980901 In response to the growing popularity of the western style paintings and the paintings of the Lingnan School which were considered to have been derived from Japanese paintings, fourteen artists formed an organization called Gui hai he zou hua she 癸亥合作畫社 (Gui Hai Painting Cooperative) in Guangzhou in 1923 with the primary aim of safeguarding the traditional style of Chinese painting.1 More artists joined this group in 1925 and the organization was renamed as Guangdong guohua yanjiu hui 廣東國畫研究會 (Guangdong National Painting Research Society) (“the Society”).2 Although the focus of most studies on Chinese art for the 20s and the 30s of the twentieth century had been placed on the artists of the Lingnan School, I believe the artists of the Society should not be neglected as they formed a strong opposition force against the Lingnan School and had significant impact on the art scene of Guangdong during that period of time. While this group of Guangdong artists continued to make paintings in the traditional genres of landscape and flowers and birds, my investigation indicates that the genre of meiren “美人” (beautiful woman) was also popular amongst them. Moreover, I will show how these artists had consulted the painting manuals and had looked at the works of the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) artist, Hua Yan 華嵒 (1682-1756) for inspiration. In this essay, I will study the meiren paintings of three core members of the Society, namely, Li Fenggong 李鳳公 (1884-1967), Huang Shaomei 黃少梅 (1886-1940) and Huang Junbi 黃君壁 (1898-1991) and why they still found the genre of meiren appealing. -

Jerome Silbergeld

SILBERGELD.CV 1 JEROME SILBERGELD P.Y. and Kinmay W. Tang Professor of Chinese Art History Director, P. Y. and Kinmay W. Tang Center for East Asian Art Affiliate Professor, East Asian Studies Department Member, East Asian Studies Program Executive Committee, Committee for Film Studies Princeton University 105 McCormick Hall Princeton, New Jersey 08544 609-258-6249 FAX 609-258-0103 [email protected] Education B.A., Stanford University, 1966 (History, with Departmental Honors) M.A., Stanford University, 1967 (History) Stanford University, 1967-68 (Ph.D. Program in History) Princeton University, 1968-69 (Ph.D. Program in Chinese Art and Archaeology) M.A., University of Oregon, 1972 (Art History, with University Honors) Ph.D., Stanford University, 1974 (Art History, with Departmental Distinction) Dissertation: "Political Symbolism in the Landscape Painting and Poetry of Kung Hsien (ca. 1620-1689)" Faculty Appointments University of Oregon, Department of Art History, Visiting Assistant Professor, 1974-75 University of Washington, Art History Program, China Studies Affiliate (Jackson School of International Studies), Cinema Studies Faculty; Assistant Professor, 1975-81; Associate Professor, 1981-87; Professor, 1987-2001; Donald E. Petersen Professor of Arts, 2000-2001; Affiliate Professor of Art History, 2001- Harvard University, Department of Fine Arts, Visiting Professor, 1996 Princeton University, P.Y. and Kinmay W. Tang Professor of Chinese Art History, Director Tang Center for Chinese and Japanese Art, Affiliate Professor of East Asian -

Lingnan Spirit Forever - a Mission in Transition, 1951-1990 : from the Trustees of Lingnan University to the Lingnan Foundation

Lingnan University Digital Commons @ Lingnan University Historical Texts of Lingnan University 嶺南大學 History of Lingnan University 歷史特藏 2002 Lingnan Spirit Forever - A Mission in Transition, 1951-1990 : From the Trustees of Lingnan University to the Lingnan Foundation Tung, Steve AU Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.ln.edu.hk/lingnan_history_bks Recommended Citation AU, Tung, Steve, "Lingnan Spirit Forever - A Mission in Transition, 1951-1990 : From the Trustees of Lingnan University to the Lingnan Foundation" (2002). Historical Texts of Lingnan University 嶺南大學歷史 特藏. 29. https://commons.ln.edu.hk/lingnan_history_bks/29 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the History of Lingnan University at Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Historical Texts of Lingnan University 嶺南大學歷史特藏 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. Lingnan Spirit Forever A Mission in Transition, T951-1990 From the Trustees of Lingnan University to the Lingnan Foundation Steven Tung Au Copyright © 2002 by the Lingnan Foundation P.O. Box 208340 New Haven, CT 06520-8340 Contents Chapter Preface v Prologue 1 1. A Poignant Farewell 6 2. The Unfinished Business 11 3. Outreach to Hong Kong Institutions 16 4. The Chinese University of Hong Kong 22 5. Lingnan Institute of Business Administration 28 6. Lingnan College 37 7. Fellowship Programs in Hong Kong 47 8. A Crack in the Bamboo Curtain 51 9. Timely Transactions for Renewal 58 10. Old Ties and New Friends 63 11. Strengthening the Channels of Communication 69 12. Projects at Zhongshan University 74 13. Lingnan (University) College 80 14. -

Environmental Impact Assessment, Guangdong, PCR Final Draft

E1187 v2 rev LIVESTOCK WASTE MANAGEMENT IN EAST ASIA Project Preparation under the PDF-B Grant Public Disclosure Authorized Annex 3A Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental Impact Assessment, Guangdong, PCR Final Draft Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared by: Dr. Zhang Yinan Department of Environmental Science, Zhongshan University Public Disclosure Authorized September, 2005 Table of Contents 1 Introduction and Project Background............................................................................... 1 1.1 Purpose of the Report ...................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Brief Introduction to the EA Report................................................................................. 2 1.2.1 Importance of the Project................................................................................... 2 1.2.2 Structure of the Report....................................................................................... 3 1.3 Bases of Assessment......................................................................................................... 3 1.3.1 Laws and Regulations........................................................................................ 3 1.3.2 Technical Documents......................................................................................... 5 1.3.3 Main Design Documents.................................................................................... 5 1.4 Principles of Environmental Assessment ........................................................................