Chinese Warriors of Peking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Circus and Acrobats of the People's Republic of China

Friday, September 11, 2015, 8pm Saturday, September 12, 2015, 2pm & 8pm Zellerbach Hall National Circus and Acrobats of the People’s Republic of China Peking Dreams Cal Performances’ $"#%–$"#& season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. PROGRAM Peking Dreams EKING (known today as Beijing), the capital of the People’s Republic of China, is a Pfamous historical and cultural city with a history spanning 1,000 years and a wealth of precious Chinese cultural heritage, including the Great Wall, the Forbidden City, the Summer Palace, and the Temple of Heaven. Acrobatic art, Chinese circus, and Peking opera are Chinese cultural treasures and are beloved among the people of Peking. These art forms combine music, acrobatics, performance, mime, and dance and share many similarities with Western culture. Foreign tourists walking along the streets or strolling through the parks of Peking can often hear natives sing beautiful Peking opera, see them play diabolo or perform other acrobatics. Peking Dreams , incorporating elements of acrobatics, Chinese circus, and Peking opera, invites audiences into an artistic world full of history and wonder. The actors’ flawless performance, colorful costumes, and elaborate makeup will astound audiences with visual and aural treats. PROGRAM Opening Acrobatic Master and His Pupils The Peking courtyard is bathed in bright moonlight. In the dim light of the training room, three children formally become pupils to an acrobatic master. Through patient teaching, the master is determined to pass his art and tradition down to his pupils. The Drunken Beauty Amidst hundreds of flowers in bloom, the imperial concubine in the Forbidden City admires the full moon while drinking and toasting. -

Catch All (Kristian Kristoff)

I, ME, MYSELF Catch all ristian Kristof believes in pushing the boundaries of his skill. The Hungarian juggler, who was in Abu Dhabi to perform at the Big Apple Circus, tells Feby Imthias that juggling is K not just about throwing balls in the air. Kristian Kristof was once speeding at the Yas Island Rotana Hotel. Kristof to finish his schooling before he step down a highway in Budapest when is in Abu Dhabi to perform at the Big into the circus ring. the inevitable happened: a patrol car Apple Circus, part of the Summer “The first time I got an opportunity flagged him down for speeding. in Abu Dhabi festival, organised by [to show off my skills] was when I was “Why are you driving so fast?” the Abu Dhabi Tourism Authority, 14 and I performed during a charity one of the policemen asked him. he took time off for an exclusive gala at the Budapest State Circus,” “I’m a juggler and I’m late for my interview with Friday. Belonging to says Kristof. show. Please sir, would you let me the fourth generation of a famous Keen to hone his skills, he enrolled go?” he pleaded. “A juggler?” they Hungarian circus family, he says he in the Hungarian State Performing asked, looking at him disbelievingly. has been travelling with the circus Arts Institute from where he “Yes,” he reiterated, then taking since he was six months old. Both his graduated in 1987. The next year out the tools from his juggling kit, parents, Istvan and Ilona, were highly he obtained a diploma from the he started demonstrating his skills respected acrobats. -

Acrobats: Building Pyramids for Their Future By: Véronique Sprenger

Acrobats: Building pyramids for their future By: Véronique Sprenger Master Thesis International Development Studies Graduate School of Social Sciences July, 2018 University of Amsterdam Graduate School of Social Sciences MSc. International Development Studies Master Thesis1 Acrobats: Building pyramids for their future What are skills that youth in Kangemi, Nairobi develop through acrobat training and how do these translate into capital that they can use in their lives? In the past there has been little research on projects that empower youth in slums through sports or performing arts. Therefore, the aim of this research is to show how youth from slums who train in acrobatics have developed skills that can help them overcome difficulties such as, unemployment and poor education. These skills will then be translated into capital that the acrobats use in their lives. These skills will be derived from one of the unique aspects of acrobatics which is that it is both a sport and a performing art. The research aims to contribute to international development research by researching a unique and local phenomenon that still has potential to be developed. The answers to the research question were obtained through qualitative analysis focusing on participant observation and interviews. The findings will show that through acrobatic training the acrobats do not only gain economic capital, but also develop skills that accumulate cultural, social, symbolic and physical capital. Some of the skills that will stand out from the research are physical strength, communication, showmanship and perseverance. Another highlight of the research is the international work opportunities that the acrobats are able to obtain. -

JUGGLING in the U.S.S.R. in November 1975, I Took a One Week Tour to Leningrad and Ring Cascade Using a "Holster” at Each Side

Volume 28. No. 3 March 1976 INTERNATIONAL JUGGLERS ASSOCIATION from Roger Dol/arhide JUGGLING IN THE U.S.S.R. In November 1975, I took a one week tour to Leningrad and ring cascade using a "holster” at each side. He twice pretended Moscow, Russia. I wasfortunate to see a number of jugglers while to accidentally miss the catch of all 9 down over his head before I was there. doing it perfectly to rousing applause and an encore bow. At the Leningrad Circus a man approximately 45 years old did Also on the show was a lady juggler who did a short routine an act which wasn’t terribly exciting, though his juggling was spinning 15-inch square glass sheets. She finished by spinning pretty good. He did a routine with 5, 4, 3 sticks including one on a stick balanced on her forehead and one on each hand showering the 5. He also balanced a pole with a tray of glassware simultaneously. Then, she did the routine of balancing a tray of on his head and juggled 4 metaf plates. For a finish, he cqnter- glassware on a sword balanced point to point on a dagger in her spun a heavy-looking round wooden table upside-down on a 10- mouth and climbing a swaying ladder ala Rosana and others. foot sectioned pole balanced on his forehead, then knocked the Finally, there were two excellent juggling acts as part of a really pole away and caught the table still spinning on a short pole held great music and variety floor show at the Arabat Restaurant in in his hands. -

Circuscape Workshops BOOKLET.Indd

CircusCape presents Fun Family Fridays, Payomet’s Circus Camp became an accredited summer camp last Super Saturdays, and more! year as a result of our high standards conforming to stringent The Art of Applying and state and local safety and operational requirements. Auditioning / Creating Our team of 5 professional Career Paths in Circus & instructors, lead by Marci Diamond, offers classes over Related Performing Arts 7-weeks for students, with Marci Diamond ages 7-14. Cost: $30 Every week will include aerial Fri 8/24 • 10-noon at Payomet Tent arts, acrobatics, juggling, mini-trampoline, physical comedy/ There are a wide range of career paths for the improv, puppeteering, object aspiring professional circus/performing artist, and manipulation, rope climbing and in this workshop, we will explore some possible physical training geared to the steps toward those dreams, as well as practical, interests and varying levels of individual students. effective approaches to applications and auditions. Applying and Auditioning for professional training programs (from short-term intensive workshops to 3 year professional training programs and universi- ty B.F.A. degrees) in circus and related performing arts, as well as for professional performance opportunities, can be a successful adventure of personal & professional growth, learning, and network-building. And it can be done with less stress than you may think! Come discuss tips for maximizing your opportunities while taking care of The core program runs yourself/your student/child. Practice your “asks and 4 days a week (Mon - Thurs) intros” with the director of the small youth circus from July 9 to August 23 at troupe, a professional circus performer and union the Payomet Tent. -

It's a Circus!

Life? It’s A Circus! Teacher Resource Pack (Primary) INTRODUCTION Unlike many other forms of entertainment, such as theatre, ballet, opera, vaudeville, movies and television, the history of circus history is not widely known. The most popular misconception is that modern circus dates back to Roman times. But the Roman “circus” was, in fact, the precursor of modern horse racing (the Circus Maximus was a racetrack). The only common denominator between Roman and modern circuses is the word circus which, in Latin as in English, means "circle". Circus has undergone something of a revival in recent decades, becoming a theatrical experience with spectacular costumes, elaborate lighting and soundtracks through the work of the companies such as Circus Oz and Cirque du Soleil. But the more traditional circus, touring between cities and regional areas, performing under the big top and providing a more prosaic experience for families, still continues. The acts featured in these, usually family-run, circuses are generally consistent from circus to circus, with acrobatics, balance, juggling and clowning being the central skillsets featured, along with horsemanship, trapeze and tightrope work. The circus that modern audiences know and love owes much of its popularity to film and literature, and the showmanship of circus entrepreneurs such as P.T. Barnum in the mid 1800s and bears little resemblance to its humble beginnings in the 18th century. These notes are designed to give you a concise resource to use with your class and to support their experience of seeing Life? It’s A Circus! CLASSROOM CONTENT AND CURRICULUM LINKS Essential Learnings: The Arts (Drama, Dance) Health and Physical Education (Personal Development) Style/Form: Circus Theatre Physical Theatre Mime Clowning Themes and Contexts: Examination of the circus style/form and performance techniques, adolescence, resilience, relationships General Capabilities: Personal and Social Competence, Critical and Creative Thinking, Ethical Behaviour © 2016 Deirdre Marshall for Homunculus Theatre Co. -

Contents About the Performers the National Acrobats of the People's

The National Acrobats of the People's Republic of China Teacher Guide October 21, 2011 http://www.cami.com/?webid=1928 Contents About the Performers About the Art Form History of Chinese Acrobatics Facts About China Learning Activities Resources About the Performers ŝƌĞĐƚĨƌŽŵĞŝũŝŶŐ͕dŚĞEĂƚŝŽŶĂůĐƌŽďĂƚƐŽĨdŚĞWĞŽƉůĞ͛ƐZĞƉƵďůŝĐŽĨŚŝŶĂ;ŚŝŶĂEĂƚŝŽŶĂůĐƌŽďĂƚŝĐdƌŽƵƉĞͿǁĂƐƚŚĞĨŝƌƐƚ EĂƚŝŽŶĂůWĞƌĨŽƌŵŝŶŐƌƚƐdƌŽƵƉĞĞƐƚĂďůŝƐŚĞĚďLJƚŚĞŐŽǀĞƌŶŵĞŶƚŽĨƚŚĞWĞŽƉůĞ͛ƐZĞƉƵďůŝĐŽĨŚŝŶĂŝŶϭϵϱϬ͘/ƚŚĂƐƉĞƌĨŽƌŵĞĚ intensively throughout the world annually around the globe. The Company's repertoire includes a myriad of International and National Gold Prize winning Acts, such as "Slack Wire" (Presidential Gold Award at the 24th Cirque de Demain Festival in Paris), "Diabolo" (Presidential Gold Award at the 26th Cirque de Demain Festival in Paris), "Pagoda of Bowls" (Golden Clown Award at ƚŚĞϮϴƚŚDŽŶƚĞĂƌůŽ/ŶƚĞƌŶĂƚŝŽŶĂůŝƌĐƵƐ&ĞƐƚŝǀĂůͿĂŶĚĂŵŽŶŐŽƚŚĞƌƐ͘dŚĞŽŵƉĂŶLJ͛ƐĐƚƐŚĂǀĞƌĞĐĞŝǀĞĚƐĞŶƐĂƚŝŽŶĂůƌĞŝǀŝĞǁƐ ďŽƚŚĂƚŚŽŵĞĂŶĚĂďƌŽĂĚĨŽƌŶƵŵďĞƌƐƐƵĐŚĂƐ͞ŚŝŶĂ^ŽƵů͕͟͞ZĞǀĞƌŝĞ͕͟͞ĐƌŽďĂƚŝĐ^ƉĞĐƚĂĐƵůĂƌ͟ĂŶĚ͞^ƉůĞŶĚŝĚ͘͟ Based in Beijing, China, the Company owns a large Institution for Acrobatic Schooling, Training and Repertoire. The Institution has over 150 Acrobatic resident performers and over 500 Acrobatic Students of all ages. Funded by a special grant from the Beijing Municipality, the Company invests each year in new productions as well as acrobatic science research and creation in addition to the training facilities of the center, which with its dedication to improvement of and renewing of Acrobatic standards has become -

Dust Palace Roving and Installation Price List 2017

ROVING AND INSTALLATION CIRQUE ENTERTAINMENT HAND BALANCE AND CONTORTION One of our most common performance installations is Hand Balance Contortion. Beautiful and graceful this incredible art is mastered by very few, highly skilled performers. Roving or installation spots are only possible for 30 mins at a time and are priced at $950+gst per performer. ADAGIO AND ACROBATICS Adagio, hand to hand, balance acrobatics and trio acro are all ways to describe the art of balancing people on people. Usually performed as a couple this is the same as hand balance contortion in that it’s only possible for 30 minute stints. Roving or installation can be performed in any style and we’re always happy to incorporate your events theme or branding into the theatrics around the skill. Performers are valued at $950+gst per 30 minute slot. MANIPULATION SKILLS Manipulation skills include; Hula Hoops, Juggling, Cigar boxes, Diabolo, Chin Balancing, Poi Twirling, Plate Spinning and Crystal Ball. As a roving or installation act these are fun and lively, bringing some nice speedy movement to the room. All are priced by the ‘performance hour’ which includes 15 minutes break and range between $400+gst and $700+gst depending on the performer and the skill. Some performers are capable of character work and audience interaction. Working these skills in synchronisation with multiple performers is a super cool look. Most of these skills can be performed with LED props. EQUILIBRISTICS aka balance skills The art of balancing on things takes many long hours of dedication to achieve even the most basic result. -

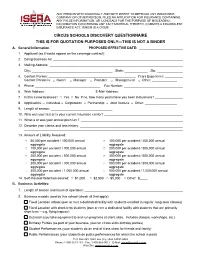

Circus Schools Discovery Questionnaire This Is for Quotation Purposes Only—This Is Not a Binder A

ANY PERSON WHO KNOWINGLY AND WITH INTENT TO DEFRAUD ANY INSURANCE COMPANY OR OTHER PERSON, FILES AN APPLICATION FOR INSURANCE CONTAINING ANY FALSE INFORMATION, OR CONCEALS FOR THE PURPOSE OF MISLEADING, INFORMATION CONCERNING ANY FACT MATERIAL THERETO, COMMITS A FRAUDULENT INSURANCE ACT, WHICH IS A CRIME. CIRCUS SCHOOLS DISCOVERY QUESTIONNAIRE THIS IS FOR QUOTATION PURPOSES ONLY—THIS IS NOT A BINDER A. General Information PROPOSED EFFECTIVE DATE: 1. Applicant (as it would appear on the coverage contract): 2. Doing Business As: 3. Mailing Address: City: State: Zip: 4. Contact Person: Years Experience: Contact Person is: □ Owner □ Manager □ Promoter □ Management □ Other: 5. Phone: Fax Number: 6. Web Address: E-Mail Address: 7. Is this a new business? □ Yes □ No If no, how many years have you been in business? 8. Applicant is: □ Individual □ Corporation □ Partnership □ Joint Venture □ Other: 9. Length of season: 10. Who was your last or is your current insurance carrier? 11. What is or was your annual premium? 12. Describe your claims and loss history: 13. Amount of Liability Required: □ 50,000 per accident / 100,000 annual □ 100,000 per accident / 200,000 annual aggregate aggregate □ 100,000 per accident / 300,000 annual □ 200,000 per accident / 300,000 annual aggregate aggregate □ 200,000 per accident / 500,000 annual □ 300,000 per accident / 500,000 annual aggregate aggregate □ 300,000 per accident / 300,000 annual □ 500,000 per accident / 500,000 annual aggregate aggregate □ 300,000 per accident / 1,000,000 annual □ 500,000 per accident / 1,000,000 annual aggregate aggregate 14. Self-Insured Retention desired: □ $1,000 □ $2,500 □ $5,000 □ Other: $ B. -

The Circus Was in Town

The Circus Was In Town Richard Duijnstee Copyright © 2019 Richard Duijnstee All rights reserved. ISBN: 9789402194128 DEDICATION For Thera, whose smile I remember every day. 1. The circus was in town. The posters were the first signs that made me aware of that: bright yellow print with red lettering and in the middle an elephant, its trunk curled, beady eyes looking at the viewer. The elephant was surrounded by six white horses, on their heads a red, fluffy plume. This was the early 1990’s, when animal rights organizations hadn’t yet won their battles and the circus with live animals didn’t realize that its glory days would soon be over. In the upper right corner of the poster was an image of a girl swinging from a trapeze. The trapeze seemed to be hanging from the big, red letter S. Over the next couple of days, glossy brochures popped up in the local stores, where you could also buy tickets to see the shows: six evening performances and three matinees. In the grocery store where I had a weekend job manning the register, I grabbed one of the brochures and brought it home to show my parents. I was 15 at the time, turning 16 in a couple of weeks. I considered myself a bit too old for the circus, but something in the poster had struck a chord and made me feel like I was a young kid again. Fortunately, my brother was six years younger than I was. He would be 1 THE CIRCUS WAS IN TOWN the perfect excuse to go. -

Jacksons Lane the Social Impact of Jacksons Lane

__ Jacksons Lane The Social Impact of Jacksons Lane August 2016 i Contents Executive Summary .............................................................................. 1 6.4 Creative skills and self-expression ............................................................... 16 6.5 Sense of belonging and reduced loneliness ................................................ 17 1. Introduction ....................................................................................... 5 6.6 Strengthened social bonds ........................................................................... 17 1.1 Jacksons Lane’s outreach activities .............................................................. 5 6.7 Increased aspirations ................................................................................... 18 1.2 Research aims and approach ........................................................................ 5 6.8 The likely long-term impact of these programmes ....................................... 18 2. Context: Haringey ............................................................................. 6 7. Conclusions .................................................................................... 20 2.1 Haringey’s demographic and economic profile ............................................. 6 2.2 Cultural infrastructure .................................................................................... 6 8. Appendix: References .................................................................... 22 2.3 Haringey’s strategic priorities -

蔡 佳 葳 Charwei Tsai Born 1980 Bonsai Series III – No

蔡 佳 葳 Charwei Tsai Born 1980 Bonsai Series III – no. VII, 2011 black ink on lithographs, 26 x 31 cm 蔡 佳 葳 DISCUSSION 1 The artist has created lithographic prints of Bonsai trees. Can you see what the artist has Charwei Tsai included on the tree in place of leaves? Born 1980 2. The words are the lyrics of love songs by the sixth Dalai Lama. Why do you think the artist Bonsai Series III – no. VII, 2011 chose to depict the Bonsai trees with these lyrics? CONTEMPORARY ART FROM MAINLAND CHINA, TAIWAN AND HONG KONG black ink on lithographs, 26 x 31 cm 3 Do you think the work has a spiritual, philosophical or religious connotation? Why? ABOUT THE ARTIST 4. How did the artist give the work a sense of time and also of movement? Charwei Tsai explores spiritual and environmental Born in Taiwan, Charwei was educated overseas, and she 5. The colour palette of the work is minimal. Why do you think Charwei decided to do this? themes through a variety of media including videos, currently lives between Taipei, Taiwan and What mood or feeling do you think it gives the work? photographs, installation and performance based works. Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. She is fascinated by Charwei often uses calligraphy to explore Buddhist concepts of impermanence and emptiness, which are texts on a range of natural surfaces such as tofu, tree central to Buddhist belief, and which the artist defines ACTIVITIES trunks, mushrooms and ice. Through a detailed and as an ‘understanding of the interdependence between Thinking repetitive process she reaches a meditative state.