Book Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Xzz^ Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal

EDITOR'S NOTE Skeptical Inquirer THE MAGAZINE I O «t SCIENCE AND REASON EDITOR Voodoo Science, and Giving Astrologers Kendrick Frazier EDITORIAL BOARD A Final Chance James E. Alcock Barry Beyerstein Thomas Casten hysicist Robert Park had already had a good career as a physics professor when Martin Gardner Phe gained some national following in the past decade among scientists and sci Ray Hyman ence writers with his weekly "What's New" electronic newsletter distributed Lawrence Jones Fridays from the Washington office of the American Physical Society. From there Philip J. Klass Paul Kurtz he has a fine vantage point for watching the foibles of those who seek to warp sci Joe Nickell ence for their own political agendas or attract public policy support for all manner Lee Nisbet of semiscientific or pseudoscientific schemes, from alternative medical fads to free- Amardeo Sarma energy machines. Now his new book Voodoo Science has thrust him into the Bela Scheiber Eugenie Scott public eye. It draws upon his knowledge of physics, understanding of Washington CONSULTING EDITORS politics, and wry outlook to explore the four aspects of what he calk voodoo Robert A. Baker science: pathological science, in which scientists fool themselves; junk science, in Susan I. Blackmore which people try to befuddle jurists or lawmakers with tortured theories of what John R. Cole Kenneth L. Feder am Id he so rather than what is so; pseudoscience, where there is no evidence but the C. E. M. Hansel language and symbols of science arc used; and fraudulent science, where honest E. C. Krupp error has evolved from self-delusion to fraud. -

Book Reviews Gullible's Travels in Psi-Land

Book Reviews Gullible's Travels in Psi-Land Mindwars: The True Story of Secret Government Research into the Military Potential of Psychic Weapons. By Ronald M. McRae. St. Martin's Press, New York, 1984. 192 pp. $12.95 Philip J. Klass HE BOOK JACKET reads: "Did you know the government is spending tax Tdollars on projects like 'Madame Zodiac' and the 'First Earth Battalion'? What is the 'psychic howitzer' and can it really blast missiles out of the sky? In this controversial book, Ron McRae documents the incredible story of official research into the military uses of parapsychology. Using interviews with confi dential inside sources along with recently declassified documents, he reveals the suppressed results of long-term top-secret research into telepathy, clairvoyance, and psychokinesis carried out by the Navy, the CIA, and the nation's most prestigious research institutes. Whether or not you believe in the powers of parapsychology, you'll be convinced that Mindwars holds profound implications for the future of warfare, science and mankind." This book convinced me that, if the government opted to sue the publisher under the truth-in-labeling laws, it would win its case handily, even allowing for the customary "hype" of book jackets. The well-known columnist Jack Anderson, who wrote the book's introduc tion, offers useful background on the author: "Ron McRae knows investigative journalism from inside and out. For several years, he was one of those 'unauthor ized sources' within the government I have always depended on. In 1979, he came in from the cold and joined my staff as an intern. -

Clever Hans's Successors Testing Indian Astrology Believers' Cognitive Dissonance Csicon Nashville Highlights

SI March April 13 cover_SI JF 10 V1 1/31/13 10:54 AM Page 2 Scotland Mysteries | Herbs Are Drugs | The Pseudoscience Wars | Psi Replication Failure | Morality Innate? the Magazine for Science and Reason Vol. 37 No. 2 | March/April 2013 ON INVISIBLE BEINGS Clever Hans’s Successors Testing Indian Astrology Believers’ Cognitive Dissonance CSICon Nashville Highlights Published by the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry March April 13 *_SI new design masters 1/31/13 9:52 AM Page 2 AT THE CEN TERFOR IN QUIRY –TRANSNATIONAL Ronald A. Lindsay, President and CEO Massimo Polidoro, Research Fellow Bar ry Karr, Ex ec u tive Di rect or Benjamin Radford, Research Fellow Joe Nickell, Senior Research Fellow Richard Wiseman, Research Fellow www.csicop.org James E. Al cock*, psy chol o gist, York Univ., Tor on to Thom as Gi lov ich, psy chol o gist, Cor nell Univ. Robert L. Park,professor of physics, Univ. of Maryland Mar cia An gell, MD, former ed i tor-in-chief, David H. Gorski, cancer surgeon and re searcher at Jay M. Pasachoff, Field Memorial Professor of New Eng land Jour nal of Med i cine Barbara Ann Kar manos Cancer Institute and chief Astronomy and director of the Hopkins Kimball Atwood IV, MD, physician; author; of breast surgery section, Wayne State University Observatory, Williams College Newton, MA School of Medicine. John Pau los, math e ma ti cian, Tem ple Univ. Steph en Bar rett, MD, psy chi a trist; au thor; con sum er Wendy M. Grossman, writer; founder and first editor, Clifford A. -

Psychic Vibrations

Psychic Vibrations : Barbie's Essence, Creationist Tactics, and Hyperspatial Hoax ROBERT SHEAFFER e've all heard about people the 60s and 70s," writes the editor, who channel the spirits of Barbara, who withholds her last name. WCro-Magnon warriors and "Since childhood I have been gifted Indian princesses, but a recent New with an intensely personal, growth- Age breakthrough apparently makes oriented relationship with Barbie, the it possible to receive messages from polyethylene essence who is 700 entities that never had spirits in the million teaching essences. Her influ- first place. From San Anselmo, Cali- ence has transformed and guided fornia, not far from San Francisco, the many of my peers through pre- Barbie Channeling Newsletter celebrates puberty to fully realized maturity. Her this feat. "I channel Barbie, archetyp- truths are too important to be pre- ical feminine plastic essence who packaged. My sincere hope is to let embodies that stereotypical wisdom of the voice of Barbie, my Inner name- twin, come through. Barbie's mes- sages are offered in love." No word yet on whether anything has been heard from Barbie's plastic boyfriend, Ken. Creationists everywhere will soon be flocking to the new Museum of Creation and Earth History, located on the top floor of the Headquarters Building of the Institute for Creation Research (ICR) near San Diego. This new 4,000-square-foot museum has a separate exhibit representing each day of Creation Week. Other exhibits center around "The Fall and the Curse." Visitors to the museum start off with a walking tour "through the newly created universe, then the Garden of Eden, followed by entrance *3£" into the regime of sin and death." Next they enter Noah's Ark, followed by 138 SKEPTICAL INQUIRER, Vol. -

Taking Intellectual Life out of Its Parallel Universe EDITORIAL BOARD James E

EDITOR'S NOTE uirer EDITOR Kendrick Frazier Taking Intellectual Life Out of Its Parallel Universe EDITORIAL BOARD James E. Alcock Barry Beyerstein he nature/nuture controversy can be irksome. That culture (environment) Thomas Casten Martin Gardner Tand our genes both contribute in a complex mixture of interactive ways to Ray Hyman everything that makes us human seems reasonable, and it is a view well sup Lawrence Jones Philip J. Klass ported by modern biological science. Yet as Steven Pinker points out in this issue, Paul Kurtz the idea that heredity plays any role at all in explaining human thought and Joe Nickell Lee Nisbet behavior "still has the power to shock.... Any claim that the mind has an innate Amardeo Sarma Bela Scheiber organization strikes people not as a hypothesis that might be correct but as a Eugenie Scott thought it is immoral to think." In "The Blank Slate," taken from his new book CONSULTING EDITORS Robert A. Baker of the same title, Pinker examines the doctrine that our minds emerge from birth Susan J. Blackmore blank, unaffected by hard-wired influences of human evolution. He maintains John R. Cole Kenneth L Feder he is not countering an extreme "nature" position with an extreme "nature" posi C. E. M. Hansel tion. But he explores "why the extreme position (diat culture is everything) is so E. C Krupp Scott O. Lilienfeld often seen as moderate, and the moderate position is seen as extreme." David F. Marks James E. Oberg Pinker, the Peter de Florez Professor of Psychology at MIT, author of How Robert Sheaffer the Mind Works and The Language Instinct, and a CSICOP Fellow, does not David E. -

Upk Bullard Pback Frontmatterrev2.Indd

© University Press of Kansas. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution prohibited without permission of the Press. Contents Acknowledgments vii Preface to the Paperback Edition ix List of Abbreviations xxiii Introduction: A Mystery of Mythic Proportions 1 1 Who Goes There? The Myth and the Mystery of UFOs 25 2 The Growth and Evolution of UFO Mythology 52 3 UFOs of the Past 97 4 From the Otherworld to Other Worlds 124 5 The Space Children: A Case Example 176 6 Secret Worlds and Promised Lands 201 7 Other Than Ourselves 229 8 Explaining UFOs: An Inward Look 252 9 Explaining UFOs: Something Yet Remains 286 Appendix: UFO-Related Web Sites 315 Notes 319 Select Bibliography 375 Index 399 An illustration section follows page 165 © University Press of Kansas. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution prohibited without permission of the Press. © University Press of Kansas. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution prohibited without permission of the Press. Acknowledgments I would like to thank Mary Castner, Mark Rodeghier, and Michael D. Swords for CUFOS, James Carrion for MUFON, Phyllis Galde for Fate magazine, Janet Bord for the Fortean Picture Library, and Richard F. Haines, whose help in providing illustrations for this book is greatly appreciated. I owe especial thanks to Jerome Clark and David M. Jacobs for reading the manu- script and devoting efforts above and beyond the call of duty to whip my unruly writ- ing into shape. A final thank-you goes to my long-suffering editor, Michael J. Briggs, who had to wait far too long for me to finish, but who did so with patience and always a helping hand. -

'Unexplained' Cases—Only If You Ignore All Explanations

SI Mar Apr 11 final_SI new design masters 1/26/11 2:16 PM Page 57 REVIEWS] mands—and cryptozoology deserves—far ‘Unexplained’ Cases—Only If more than brief anecdotes from anony- mous eyewitnesses. One drawback of the You Ignore All Explanations book (especially for anyone wishing to use it as a resource) is the lack of references or even an index. Especially in a book with ROBERT SHEAFFER chapters that are often collections of vari- ous reports on various monsters, an index would have been invaluable. With its limita- hile UFO believers have held for UFOs: Generals, tions in mind, the book is definitely worth a look for cryptozoology enthusiasts. Wdecades that “disclosure” is just Pilots, and Government around the corner, the modern disclo- Officials Go on the sure movement is savvy enough to re- Record alize that “disclosure” needs a little By Leslie Kean. THE OTHER SIDE: A Teen’s Guide to Ghost push. On May 9, 2001, Steven Greer’s Harmony Books, Hunting and the Paranormal. Marley Gib- New York, 2010. ISBN: son, Patrick Burns, and Dave Schrader. Disclosure Project held a press confer- Houghton Mifflin, New York. 2010. 112 pp. 978-0-307-71684-2. ence at the National Press Club in Paperback, $10.99. A recent addition to the Washington, D.C., featuring twenty 335 pp. Hardcover, explosion of ghost books people who have made claims of a $25.99. aimed at teens, The Other widespread government conspiracy to Side deems itself a practi- fesses (a bit disingenuously) to be ag- cal guide to ghost hunting conceal the existence of extraterrestrial and the paranormal. -

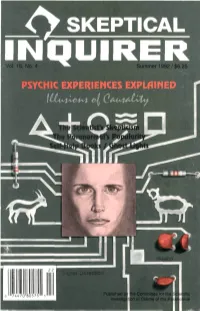

Psychic Experiences Explained

SKEPTICAL INQUIRER Vol. 16PSYCHI No. 4 C EXPERIENCES EXPLAINED The Scientist's Skepticism The Paranormal's Popularity Self-Help Books/Ghost Lights Published by the Commute Investigation of Claims of the PParanormaa an l THE SKEPTICAL INQUIRER (ISSN 0194-6730) is the official journal of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal, an international organization. Editor Kendrick Frazier. Editorial Board James E. Alcock, Martin Gardner, Ray Hyman, Philip J. Klass, Paul Kurtz. Consulting Editors Isaac Asimov, William Sims Bainbridge, John R. Cole, Kenneth L. Feder, C. E. M. Hansel, E. C. Krupp, David F. Marks, Andrew Neher, James E. Oberg, Robert Sheaffer, Steven N. Shore. Managing Editor Doris Hawley Doyle. Contributing Editor Lys Ann Shore. Business Manager Mary Rose Hays. Assistant Business Manager Sandra Lesniak Chief Data Officer Richard Seymour. Computer Assistant Michael Cione. Production Paul E. Loynes. Audio Technician Vance Vigrass. Librarian, Ranjit Sandhu. Staff Leland Harrington, Jonathan Jiras, Atfreda Pidgeon, Kathy Reeves, Elizabeth Begley (Albuquerque). Cartoonist Rob Pudim. The Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy, State University of New York at Buffalo. Barry Karr, Executive Director and Public Relations Director. Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director. Fellows of the Committee James E. Alcock, psychologist, York Univ., Toronto; Isaac Asimov, biochemist, author; Robert A. Baker, psychologist, Univ. of Kentucky; Barry Beyerstein, biopsychologist, Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, B.C., Canada; Irving Biederman, psychologist, University of Minnesota; Susan Blackmore, psychologist, Brain Perception Laboratory, University of Bristol, England; Henri Broch, physicist, University of Nice, France; Vern Bullough, Distinguished Professor, State University of New York; Mario Bunge, philosopher, McGill University; John R. -

MOON MYTHS Cool Light on Lunar-Effect Claims

the Skeptical Inquirer MOON MYTHS Cool Light on Lunar-Effect Claims Soviet Psi Studies Psychopathology of Fringe Medicine Computers and Psi London CSICOP Conference VOL. X NO. 2/WINTER 1985* $5.00 Published by the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Skeptical Inquirer THE SKEPTICAL INQUIRER is the official journal of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal. Editor Kendrick Frazier. Editorial Board James E. Alcock. Martin Gardner, Ray Hyman, Philip J. Klass, Paul Kurtz, James Randi. Consulting Editors Isaac Asimov, William Sims Bainbridge. John Boardman. John R. Cole, C. E. M. Hansel. E. C. Krupp, Andrew Neher. James E. Oberg, Robert Sheaffer, Steven N. Shore. Managing Editor Doris Hawley Doyle. Public Relations Andrea Szalanski (director). Barry Karr. Production Editor Betsy Offermann. Business Manager Mary Rose Hays. Systems Programmer Richard Seymour, Data-Base Manager Laurel Geise Smith. Typesetting Paul E. Loynes. Staff Stephanie Doyle, Mary Beth Gehrman, Ruthann Page, Alfreda Pidgeon. Vance Vigrass. Cartoonist Rob Pudim. The Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Paul Kurtz. Chairman; philosopher. Stale University of New York at Buffalo. Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director. Fellows of the Committee James E. Alcock, psychologist, York Univ., Toronto; Eduardo Amaldi, physicist. University of Rome, Italy. Isaac Asimov, biochemist, author; Irving Biederman, psychologist, SUNY at Buffalo; Brand Blanshard, philosopher. Yale; Mario Bunge, philosopher, McGill University; Bette Chambers, AHA.; John R. Cole, anthropologist. Institute for the Study of Human Issues; F. H. C. Crick, biophysicist. Salk Institute for Biological Studies, La Jolla, Calif.; L. Sprague de Camp, author, engineer; Bernard Dixon, science writer, consultant; Paul Edwards, philos opher. -

Critique of Serious Astrology / Science, Magic, & Metascience Velikovsky

the Skeptical Inquirer Critique of Serious Astrology / Science, Magic, & Metascience Velikovsky and China / Follow-ups on Ions, Hundredth Monkey VOL. XI NO. 3 / SPRING 1987 $5.00 Published by the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Skeptical Inquirer _ THE SKEPTICAL INQUIRER is the official journal of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal. Editor Kendrick Frazier. Editorial Board James E. Alcock, Martin Gardner, Ray Hyman, Philip J. (Class, Paul Kurtz, James Randi. Consulting Editors Isaac Asimov, William Sims Bainbridge, John R. Cole, Kenneth L. Feder, C. E. M. Hansel, E. C. Krupp, Andrew Neher, James E. Oberg, Robert Sheaffer, Steven N. Shore. Managing Editor Doris Hawley Doyle. Public Relations Andrea Szalanski (director), Barry Karr. Production Editor Kelli Sechrist. Business Manager Mary Rose Hays. Systems Programmer Richard Seymour. Typesetting Paul E. Loynes. Audio Technician Vance Vigrass. Librarian, Peter Kalshoven. Staff Norman Forney, Mary Beth Gehrman, Diane Gerard, Erin O'Hare, Alfreda Pidgeon, Andrea Sammarco, Lori Van Amburgh. Cartoonist Rob Pudim. The Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Paul Kurtz, Chairman; philosopher, State University of New York at Buffalo. Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director. Mark Plummer, Acting Executive Director. Fellows of the Committee James E. Alcock, psychologist, York Univ., Toronto; Eduardo Amaldi, physicist, University of Rome, Italy. Isaac Asimov, biochemist, author; Irving Biederman, psychologist, SUNY at Buffalo; Brand Blanshard, philosopher, Yale; Mario Bunge, philosopher, McGill University; Bette Chambers, A.H.A.; John R. Cole, anthropologist. Institute for the Study of Human Issues; F. H. C. Crick, biophysicist, Salk Institute for Biological Studies, La Jolla, Calif.; L. -

Skeptical Inquirer EDITOR's NOTE the MAGA21NI (Ol SCIINCI and MASON EDITOR Kendrick Frazier EDITORIAL BOARD the Skepticism of Inclusion James E

Skeptical Inquirer EDITOR'S NOTE THE MAGA21NI (Ol SCIINCI AND MASON EDITOR Kendrick Frazier EDITORIAL BOARD The Skepticism of Inclusion James E. Alcock Barry Beyerstein Thomas Casten s we near the turn of the millennium, the modern skeptical movement has an Martin Gardner opportunity to broaden its outreach and appeal. Ray Hyman A Lawrence Jones How? Here arc some suggestions: Philip J. Klass • Take every opportunity to show that science (and the critical inquiry that is a Paul Kurtz Joe Nickell key part of it) is fun, interesting, positive, challenging, provocative, life-changing, civ Lee Nisbet ilization-advancing, awe-inspiring. Amardeo Sarma • Show that science is open to all new ideas, actively welcomes new evidence and Bela Scheiber Eugenie Scott explanatory theories, and loves overturning previously held precepts. It can be revo CONSULTING EDITORS lutionary. Scientists, in fact, arc happiest when they are lucky enough to be partici Robert A. Baker pating in a true scientific revolution. The only criterion: All new evidence must Susan J. Blackmore John R. Cole repeatedly be subjected to, and pass, rigorous testing. Kenneth L. Feder • Emphasize the positive that skepticism is common sense in action; in addition C. E. M. Hansel E. C. Krupp to its crucial role in science, it is a necessary part of everyday life that we all use and Scott O. Lilienfeld embrace. It is not elitist. To the contrary, it is the most democratic of attributes. We David F. Marks all have it and can put it into action on our own behalf. When we kick the tires, check James E. -

News and Comment

News and Comment Notes on the 1980 National UFO Conference The seventeenth annual National UFO release all government UFO informa Conference was held at the Doral Inn in tion. The various presidential candi New York City last summer. I was one dates were called upon to take a public of the invited speakers. The names of position on UFOs and to state whether the participants and of those in or not they would end the alleged cover- attendance were a "who's who" of up of UFO secrets. (At that time UFOlogy. The principal organizer and Ronald Reagan and Gerald Ford were venture capitalist of the conference was directly across the street at a fund- James W. Moseley of Gutenberg, New raising affair in the Waldorf Astoria, Jersey, a long-time UFO enthusiast. but they took no notice of the Day One: New York City free challenge.) Luckman made much of the lance artist George A. Rackus set up his supposed UFO sighting by Jimmy sculpted "close encounter" alien heads Carter. When my turn came to speak, I (see photo) in the room where the press pointed out that Jimmy Carter's conference was about to begin. Stanton "UFO" was almost certainly the planet T. Friedman, who calls himself the Venus. Stanton Friedman agreed that "Flying Saucer Physicist," strongly ob Carter probably did not see a genuine jected to this display, calling it "creative UFO and that the case has little merit. fiction." However, he approved of a Friedman disagreed that the object similar sculpture of an alien head that sighted was Venus, but he did not say alleged UFO-abductee Betty Hill car exactly what he thought it was.