A Poem on the Mutilation of Brian Og 0 Neill (D. 1449)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Celtic Encyclopedia, Volume II

7+( &(/7,& (1&<&/23(',$ 92/80( ,, . T H E C E L T I C E N C Y C L O P E D I A © HARRY MOUNTAIN VOLUME II UPUBLISH.COM 1998 Parkland, Florida, USA The Celtic Encyclopedia © 1997 Harry Mountain Individuals are encouraged to use the information in this book for discussion and scholarly research. The contents may be stored electronically or in hardcopy. However, the contents of this book may not be republished or redistributed in any form or format without the prior written permission of Harry Mountain. This is version 1.0 (1998) It is advisable to keep proof of purchase for future use. Harry Mountain can be reached via e-mail: [email protected] postal: Harry Mountain Apartado 2021, 3810 Aveiro, PORTUGAL Internet: http://www.CeltSite.com UPUBLISH.COM 1998 UPUBLISH.COM is a division of Dissertation.com ISBN: 1-58112-889-4 (set) ISBN: 1-58112-890-8 (vol. I) ISBN: 1-58112-891-6 (vol. II) ISBN: 1-58112-892-4 (vol. III) ISBN: 1-58112-893-2 (vol. IV) ISBN: 1-58112-894-0 (vol. V) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mountain, Harry, 1947– The Celtic encyclopedia / Harry Mountain. – Version 1.0 p. 1392 cm. Includes bibliographical references ISBN 1-58112-889-4 (set). -– ISBN 1-58112-890-8 (v. 1). -- ISBN 1-58112-891-6 (v. 2). –- ISBN 1-58112-892-4 (v. 3). –- ISBN 1-58112-893-2 (v. 4). –- ISBN 1-58112-894-0 (v. 5). Celts—Encyclopedias. I. Title. D70.M67 1998-06-28 909’.04916—dc21 98-20788 CIP The Celtic Encyclopedia is dedicated to Rosemary who made all things possible . -

Manx Place-Names: an Ulster View

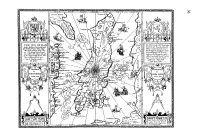

37 Manx Place-Names: an Ulster View Kay Muhr In this chapter I will discuss place-name connections between Ulster and Man, beginning with the early appearances of Man in Irish tradition and its association with the mythological realm of Emain Ablach, from the 6th to the I 3th century. 1 A good introduction to the link between Ulster and Manx place-names is to look at Speed's map of Man published in 1605.2 Although the map is much later than the beginning of place-names in the Isle of Man, it does reflect those place-names already well-established 400 years before our time. Moreover the gloriously exaggerated Manx-centric view, showing the island almost filling the Irish sea between Ireland, Scotland, England and Wales, also allows the map to illustrate place-names from the coasts of these lands around. As an island visible from these coasts Man has been influenced by all of them. In Ireland there are Gaelic, Norse and English names - the latter now the dominant language in new place-names, though it was not so in the past. The Gaelic names include the port towns of Knok (now Carrick-) fergus, "Fergus' hill" or "rock", the rock clearly referring to the site of the medieval castle. In 13th-century Scotland Fergus was understood as the king whose migration introduced the Gaelic language. Further south, Dundalk "fort of the small sword" includes the element dun "hill-fort", one of three fortification names common in early Irish place-names, the others being rath "ring fort" and lios "enclosure". -

Honour and Early Irish Society: a Study of the Táin Bó Cúalnge

Honour and Early Irish Society: a Study of the Táin Bó Cúalnge David Noel Wilson, B.A. Hon., Grad. Dip. Data Processing, Grad. Dip. History. Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Masters of Arts (with Advanced Seminars component) in the Department of History, Faculty of Arts, University of Melbourne. July, 2004 © David N. Wilson 1 Abstract David Noel Wilson, Honour and Early Irish Society: a Study of the Táin Bó Cúalnge. This is a study of an early Irish heroic tale, the Táin Bó Cúailnge (The Cattle Raid of the Cooley). It examines the role and function of honour, both within the tale and within the society that produced the text. Its demonstrates how the pursuit of honour has influenced both the theme and structure of the Táin . Questions about honour and about the resolution of conflicting obligations form the subject matter of many of the heroic tales. The rewards and punishments of honour and shame are the primary mechanism of social control in societies without organised instruments of social coercion, such as a police force: these societies can be defined as being ‘honour-based’. Early Ireland was an honour- based society. This study proposes that, in honour-based societies, to act honourably was to act with ‘appropriate and balanced reciprocity’. Applying this understanding to the analysis of the Táin suggests a new approach to the reading the tale. This approach explains how the seemingly repetitive accounts of Cú Chulainn in single combat, which some scholars have found wearisome, serve to maximise his honour as a warrior in the eyes of the audience of the tale. -

Download the Programme for the Xvith International Congress of Celtic Studies

Logo a chynllun y clawr Cynlluniwyd logo’r XVIeg Gyngres gan Tom Pollock, ac mae’n seiliedig ar Frigwrn Capel Garmon (tua 50CC-OC50) a ddarganfuwyd ym 1852 ger fferm Carreg Goedog, Capel Garmon, ger Llanrwst, Conwy. Ceir rhagor o wybodaeth ar wefan Sain Ffagan Amgueddfa Werin Cymru: https://amgueddfa.cymru/oes_haearn_athrawon/gwrthrychau/brigwrn_capel_garmon/?_ga=2.228244894.201309 1070.1562827471-35887991.1562827471 Cynlluniwyd y clawr gan Meilyr Lynch ar sail delweddau o Lawysgrif Bangor 1 (Archifau a Chasgliadau Arbennig Prifysgol Bangor) a luniwyd yn y cyfnod 1425−75. Mae’r testun yn nelwedd y clawr blaen yn cynnwys rhan agoriadol Pwyll y Pader o Ddull Hu Sant, cyfieithiad Cymraeg o De Quinque Septenis seu Septenariis Opusculum, gan Hu Sant (Hugo o St. Victor). Rhan o ramadeg barddol a geir ar y clawr ôl. Logo and cover design The XVIth Congress logo was designed by Tom Pollock and is based on the Capel Garmon Firedog (c. 50BC-AD50) which was discovered in 1852 near Carreg Goedog farm, Capel Garmon, near Llanrwst, Conwy. Further information will be found on the St Fagans National Museum of History wesite: https://museum.wales/iron_age_teachers/artefacts/capel_garmon_firedog/?_ga=2.228244894.2013091070.156282 7471-35887991.1562827471 The cover design, by Meilyr Lynch, is based on images from Bangor 1 Manuscript (Bangor University Archives and Special Collections) which was copied 1425−75. The text on the front cover is the opening part of Pwyll y Pader o Ddull Hu Sant, a Welsh translation of De Quinque Septenis seu Septenariis Opusculum (Hugo of St. Victor). The back-cover text comes from the Bangor 1 bardic grammar. -

Espelhos Distorcidos: O Romance at Swim- Two-Birds De Flann O'brien E a Tradição Literária Irlandesa

Universidade de Brasília Instituto de Letras Departamento de Teoria Literária e Literaturas Paweł Hejmanowski Espelhos Distorcidos: o Romance At Swim- Two-Birds de Flann O'Brien e a Tradição Literária Irlandesa Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Literatura para obtenção do título de Doutor, elaborada sob orientação da Profa. Dra. Cristina Stevens. Brasília 2011 IN MEMORIAM PROFESSOR ANDRZEJ KOPCEWICZ 2 Agradeço a minha colega Professora Doutora Cristina Stevens. A conclusão do presente estudo não teria sido possível sem sua gentileza e generosidade. 3 RESUMO Esta tese tem como objeto de análise o romance At Swim-Two-Birds (1939) do escritor irlandês Flann O’Brien (1911-1966). O romance pode ser visto, na perspectiva de hoje, como uma das primeiras tentativas de se implementar a poética de ficção autoconsciente e metaficção na literatura ocidental. Publicado na véspera da 2ª Guerra, o livro caiu no esquecimento até ser re-editado em 1960. A partir dessa data, At Swim-Two-Birds foi adquirindo uma reputação cult entre leitores e despertando o interesse crítico. Ao lançar mão do conceito mise en abyme de André Gide, o presente estudo procura mapear os textos dos quais At Swim-Two-Birds se apropria para refletí-los de forma distorcida dentro de sua própria narrativa. Estes textos vão desde narrativas míticas e históricas, passam pela poesia medieval e vão até os meados do século XX. Palavras-chave: Intertextualidade, Mis en abyme, Literatura e História, Romance Irlandês do séc. XX, Flann O’Brien. ABSTRACT The present thesis analyzes At Swim-Two-Birds, the first novel of the Irish author Flann O´Brien (1911-1966). -

O Maolalaigh, R. (2019) Fadó: a Conservative Survival in Irish? Éigse: a Journal of Irish Studies, 40, Pp

O Maolalaigh, R. (2019) Fadó: A Conservative Survival in Irish? Éigse: A Journal of Irish Studies, 40, pp. 207-225. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/165727/ Deposited on 9 August 2018 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Fadó: A Conservative Survival in Irish? Building on the insightful interpretations provided by Thurneysen (GOI), R. A. Breatnach (1951; 1954), Binchy (1984) and Hamp (1990), this brief contribution suggests an alternative explanation for the etymology and origin of the commonly used Irish adverb fadó (‘long ago’). It proposes a relation with the final element of the ancient legal phrase co nómad n-áu / n-ó and explores the possible connection with Manx er dy (‘since’). The temporal adverb fadó (‘long ago’) survives in Irish but is not found in Scottish Gaelic. The case for the possible survival of fadó in Manx is tentatively made in the appendix. The nearest equivalent in Scottish Gaelic is fada bhuaidh(e) (‘long ago, a long time ago’) – discussed further below – and (bh)o chionn f(h)ada: see, for instance, LASID IV (q. 726, pts a–g; q. 1035, pt c). In traditional tales, we find o chionn fada; o chionn tìm fhada; bho shean, etc. (e.g. McKay 1940–60, II: 54, 88, 358, 17).1 In Scotland, fada is often used with the simple preposition / conjunction (bh)o, e.g. -

Irish Immigration to America, 1630 to 1921 by Dr

Irish Immigration to America, 1630 to 1921 By Dr. Catherine B. Shannon Reprinted courtesy of the New Bedford Whaling Museum Introduction The oft quoted aphorism that "Boston is the next parish to Galway" highlights the long and close connections between Ireland and New England that extend as far back as the 1600s. Colonial birth, death, marriage, and some shipping records cite the presence of Irish born people as early as the 1630s. For instance, in 1655 the ship Goodfellow arrived in Boston carrying a group of indentured servants, and John Hancock's ancestor, Anthony Hancock, arrived from Co. Down in 1681. According to the story of The Irish Gift of 1676, which provided aid after King Phillip's War, Rev. Cotton Mather and Governor Winthrop corresponded with their Irish friends and relatives, with as many as 105 soldiers of Irish origin serving in various militias during the war. However, up until 1715, the numbers of Irish in New England were less than 1%, a small percentage of the population.1 The First Wave of Irish Immigration, 1715 to 1845 The first significant influx of Irish immigrants to Boston and New England consisted primarily of Ulster Presbyterians and began in the early eighteenth century.2 They comprised about ten percent, or 20,000 of a larger migration of over 200,000 Ulster Presbyterians who fled the north of Ireland to America between 1700 and 1775. The majority arrived in Boston between 1714 and 1750, as most Ulster immigrants went to the mid-Atlantic area via Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Charleston beginning in the 1750s. -

1 FIONN in HELL an Anonymous Early Sixteenth-Century Poem In

1 FIONN IN HELL An anonymous early sixteenth-century poem in Scots describes Fionn mac Cumhaill as having ‘dang þe devill and gart him ʒowle’ (‘struck the Devil and made him yowl’) (Fisher 1999: 36). The poem is known as ‘The Crying of Ane Play.’ Scots literature of the late medieval and early modern period often shows a garbled knowledge of Highland culture; commonly portraying Gaels and their language and traditions negatively. Martin MacGregor notes that Lowland satire of Highlanders can, ‘presuppose some degree of understanding of the language, and of attendant cultural and social practices’ (MacGregor 2007: 32). Indeed Fionn and his band of warriors, 1 collectively Na Fiantaichean or An Fhèinn0F in modern Scottish Gaelic, are mentioned a number of times in Lowland literature of the period (MacKillop 1986: 72-74). This article seeks to investigate the fate of Fionn’s soul in late medieval and early modern Gaelic literature, both Irish and Scottish. This is done only in part to consider if the yowling Devil and his encounter with Fionn from the ‘The Crying of Ane Play’ might represent something recognizable from contemporaneous Gaelic literature. Our yowling Devil acts here as something of a prompt for an investigation of Fionn’s potential salvation or damnation in a number of sixteenth-century, and earlier, Gaelic ballads. The monumental late twelfth- or early thirteenth-century (Dooley 2004) text Acallam na 2 Senórach (‘The Colloquy of the Ancients’) will also be considered here.1F Firstly, the Scots poem must be briefly investigated in order to determine its understanding of Gaelic conventions. -

MAY 2018 News for AOH Fr

MAY 2018 News for AOH Fr. Con C. Woulfe Division 1 Ulster County Bill Kearney, Editor P.O. Box 2026 Neil Murray, Columnist/Historian AOH Jean Steuding, Columnist LAOH Kingston, NY 12402 Fr. Edmund Burke, Chaplain AOH www.ulsteraoh.com Fr. John Kearney, Chaplain LAOH Jim Carey, President AOH Division 1 Patricia Clausi, President LOAH Division 5 NEXT MEETING Citizen Army and James TUESDAY Connolly. The major difference between this uniform and that of MAY 8, 2018 the Volunteers is in that hat. 7:30 PM The Citizen Army, including WHITE EAGLE HALL Padraig Pierce, wore slouch DELAWARE AVENUE hats. The Irish Volunteers KINGSTON, NY CIVILIAN CLOTHING themselves, wore hats similar to that of the British Service cap of On Easter Monday 1916, the the era with the proper Irish Cap Irish Volunteers who took part badge. In both cases, uniform in the Rising wore a variety of buttons would have been THE uniforms. The four main types adorned with a Harp, the official HISTORIAN’S CORNER were that of the Citizen Army, symbol of Ireland, and the Contributing Reporter Neil Murray the Na-Fianna-Eireann, and that initials IV, for Irish Volunteers. of simple civilian clothing. Tunic (jacket), trousers, and IRISH VOLUNTEER What might be surprising, is the puttees (wool leg wraps) would UNIFORMS OF THE most common uniform worn, have been made of green wool. EASTER RISING was simply put, civilian The cap badge and symbol even clothing. Tweed jackets, today of the Óglaigh na waistcoats, and trousers of hÉireann or Irish Defense forces black, brown, grey, or navy, is a bit complex in its origin and with or without pinstripes, is based more on symbolism would have been the most than an actual translation. -

Stress Placement in Munster Irish* 1 Antony Dubach Green Cornell University

[NB: This is work in progress. Please send comments to me at [email protected] !] Stress Placement in Munster Irish* 1 Antony Dubach Green Cornell University 0. INTRODUCTION While the Irish dialects of Connacht and Ulster show initial stress on almost all words, in the Munster dialect, stress is attracted to heavy syllables (by which we mean syllables containing a long vowel or diphthong, not CVC syllables) in a complicated manner. In this paper I will propose the binary colon (Halle & Clements 1983, Hammond 1987, Hayes 1995) to account for the placement of stress in Munster Irish (MI). Previous analyses of stress in MI include van Hamel (1926), O’Rahilly (1932), Blankenhorn (1981), Ó Sé (1989), Doherty (1991), and Gussmann (1995). The facts here are complicated; for specifics, refer to the data below, which are taken from the following sources: BB (= Ó Cuív 1947), CD (= Ó hÓgáin 1984), DOC (= Dillon & Ó Cróinín 1961), H (= Holmer 1962), L (= Loth 1913), LA (= Wagner 1964), Mk (= Ó Cuív 1944), Rg (= Breatnach 1947), S (= Sommerfelt 1927), SCD (= Breatnach 1961). Occasionally I have quoted forms directly from Gussmann when I could not find them in a primary source. Further information on the Munster dialect can be found in Sjoestedt-Jonval (1938), Nic Pháidín (1987), Ó hAirt (1988), and Ua Súilleabháin (1994). In § 1 I give the data that show the idiosyncratic manner in which stress is attracted to heavy syllables. (Coda consonants do not contribute to weight in Irish, so heavy syllables are only those that contain a long vowel or a diphthong.) In § 2 I give the data relating to the fact that the vowel a in the second syllable attracts stress like a heavy syllable when it is followed by x, either in the same syllable or in the next syllable. -

Contributors

CONTRIBUTORS T. B. Barry Aidan Breen Trinity College Dublin National University of Ireland, Maynooth Black Death; Manorialism; Motte-and-Baileys; Adomnán; Áed Mac Crimthainn; Blathmac; Classical Waterford Influence; Cogitosus; Dícuil; Grammatical Treatises; Literature, Hiberno-Latin; Marriage; Muirchú; Poetry, Rolf Baumgarten Hiberno-Latin Literature; Records, Ecclesiastical; Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies Rhetoric; Sciences Etymology Stephen Brown Jacqueline Borsje University of Wisconsin-Madison Universiteit Utrecht Education Witchcraft and Magic Paul Byrne Cormac Bourke Department of Finance, Dublin Ulster Museum, Belfast Diarmait mac Cerbaill; Lóegaire Mac Neill; Mide; Reliquaries Niall Noígiallach; Uí Néill; Uí Néill, Northern; Uí Néill, Southern John Bradley National University of Ireland, Maynooth Michael Byrnes Bridges; Carolingian; Kildare; Kilkenny; Dun Laoghaire, Co. Dublin, Ireland Mills and Milling; Tara; Trim; Villages; Céli Dé; Feis; Máel-Ruain; Tribes; Tuarastal; Walled Towns Túath Paul Brand Letitia Campbell All Souls College, Oxford Trinity College Dublin Common Law; Courts; Local Government; March Cormac mac Cuilennáin; Éoganachta; Fedelmid mac Law; Modus Tenendi Parliamentum; Records, Crimthainn; Mac Carthaig, Cormac Administrative; Wills and Testaments Howard Clarke Dorothy-Ann Bray University College Dublin McGill University, Montreal Dublin; Fraternities and Guilds; Population; Urban Brigit; Íte; Mo-Ninne Administration Anne Connon Caoimhín Breatnach National University of Ireland, Galway University College -

The Cathach of Colum Cille

The Cathach οτ Colum Cille An introduction ky Micnael Herity ana Aiaan Breen '*V> lat . [ ^Ονάνάτ» e»<JTTriTrer«oTvetTnef O sfefrcinobp^obTviomOaTiCiÄccuTcerTne- ö?<xfo TnTflrc«arTnirrerwOOT\2>i am-fùcCTT« Äoeruw* eemfîj «tun >-*~ flirt otm numtfertœr^Tvumct^v^cUSir^TX^tiCLe-— TncnTinemcer«^nT»^torwtcüu«u,- __ƒ__ ^ |m>»nt>taurauuenuntr ta Oüfi&srTmorr J Folio 21r of the Caihach showing initial M and beginning of Psalm 56. Tne Cathach of Colum Cille An introduction h Micnael Herity and Aidan Breen Royal Irisn Academy 2002 First published in 2002 by the Royal Irish Academy 19 Dawson Street Dublin 2 Ireland www.ria.ie © Royal Irish Academy All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, by any means now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, without either the prior written consent of the Royal Irish Academy or a license permitting restricted copying in Ireland issued by the Irish Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, Irish Writers' Centre, 19 Parnell Square, Dublin 1. Every effort has been made to contact and obtain permission from holders of copyright. If any involuntary infringement of copyright has occurred, sincere apologies are offered, and the owner of such copyright is requested to contact the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library. ISBN 1-874045-92-5 (with CD-ROM) 1-874045-97-6 (without CD-ROM) Design and layout by Martello Media Ltd, Dublin