The Mechanical Monster and Discourses of Fear and Fascination in the Early History of the Computer ✉ Hannah Grenham 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter Fourteen Men Into Space: the Space Race and Entertainment Television Margaret A. Weitekamp

CHAPTER FOURTEEN MEN INTO SPACE: THE SPACE RACE AND ENTERTAINMENT TELEVISION MARGARET A. WEITEKAMP The origins of the Cold War space race were not only political and technological, but also cultural.1 On American television, the drama, Men into Space (CBS, 1959-60), illustrated one way that entertainment television shaped the United States’ entry into the Cold War space race in the 1950s. By examining the program’s relationship to previous space operas and spaceflight advocacy, a close reading of the 38 episodes reveals how gender roles, the dangers of spaceflight, and the realities of the Moon as a place were depicted. By doing so, this article seeks to build upon and develop the recent scholarly investigations into cultural aspects of the Cold War. The space age began with the launch of the first artificial satellite, Sputnik, by the Soviet Union on October 4, 1957. But the space race that followed was not a foregone conclusion. When examining the United States, scholars have examined all of the factors that led to the space technology competition that emerged.2 Notably, Howard McCurdy has argued in Space and the American Imagination (1997) that proponents of human spaceflight 1 Notably, Asif A. Siddiqi, The Rocket’s Red Glare: Spaceflight and the Soviet Imagination, 1857-1957, Cambridge Centennial of Flight (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010) offers the first history of the social and cultural contexts of Soviet science and the military rocket program. Alexander C. T. Geppert, ed., Imagining Outer Space: European Astroculture in the Twentieth Century (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012) resulted from a conference examining the intersections of the social, cultural, and political histories of spaceflight in the Western European context. -

The Last of the Dinosaurs

020063_TimeMachine22.qxd 8/7/01 3:26 PM Page 1 020063_TimeMachine22.qxd 8/7/01 3:26 PM Page 2 This book is your passport into time. Can you survive in the Age of Dinosaurs? Turn the page to find out. 020063_TimeMachine22.qxd 8/7/01 3:26 PM Page 3 The Last of the Dinosaurs by Peter Lerangis illustrated by Doug Henderson A Byron Preiss Book 020063_TimeMachine22.qxd 8/7/01 3:26 PM Page 4 To Peter G. Hayes, for his friendship, interest, and help Copyright @ 1988, 2001 by Byron Preiss Visual Publications “Time Machine” is a registered trademark of Byron Preiss Visual Publications, Inc. Registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark office. Cover painting by Mark Hallett Cover design by Alex Jay An ipicturebooks.com ebook ipicturebooks.com 24 West 25th St., 11th fl. NY, NY 10010 The ipicturebooks World Wide Web Site Address is: http://www.ipicturebooks.com Original ISBN: 0-553-27007-9 eISBN: 1-59019-087-4 This Text Converted to eBook Format for the Microsoft® Reader. 020063_TimeMachine22.qxd 8/7/01 3:26 PM Page 5 ATTENTION TIME TRAVELER! This book is your time machine. Do not read it through from beginning to end. In a moment you will receive a mission, a special task that will take you to another time period. As you face the dan- gers of history, the Time Machine often will give you options of where to go or what to do. This book also contains a Data Bank to tell you about the age you are going to visit. -

Exploring the Social, Moral, and Temporal Qualities of Pre-Service

Exploring the Social, Moral, and Temporal Qualities of Pre-Service Teachers’ Narratives of Evolution Deirdre Hahn Division of Psychology in Education, College of Education, Arizona State University, PO Box 878409, Tempe, Arizona 85287 [email protected] Sarah K Brem Division of Psychology in Education, College of Education, Arizona State University, PO Box 870611, Tempe, Arizona 85287 [email protected] Steven Semken Department of Geological Sciences, Arizona State University, PO Box 871404, Tempe, Arizona 85287 [email protected] ABSTRACT consequences of accepting evolutionary theory. That is, both evolutionists and creationists tend to believe that Elementary, middle, and secondary school teachers may accepting evolutionary theory will result in a greater experience considerable unease when teaching evolution ability to justify or engage in racist or selfish behavior, in the context of the Earth or life sciences (Griffith and and will reduce people's sense of purpose and Brem, in press). Many factors may contribute to their self-determination. Further, Griffith and Brem (in press) discomfort, including personal conceptualizations of the found that in-service science teachers frequently share evolutionary process - especially human evolution, the these same beliefs and to avoid controversy in the most controversial aspect of evolutionary theory. classroom, the teachers created their own boundaries in Knowing more about the mental representations of an curriculum and teaching practices. evolutionary process could help researchers to There is a historical precedent for uneasiness around understand the challenges educators face in addressing evolutionary theory, particularly given its use to explain scientific principles. These insights could inform and justify actions performed in the name of science. -

Retrofuture Hauntings on the Jetsons

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Queens College 2020 No Longer, Not Yet: Retrofuture Hauntings on The Jetsons Stefano Morello CUNY Graduate Center How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/qc_pubs/446 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] de genere Rivista di studi letterari, postcoloniali e di genere Journal of Literary, Postcolonial and Gender Studies http://www.degenere-journal.it/ @ Edizioni Labrys -- all rights reserved ISSN 2465-2415 No Longer, Not Yet: Retrofuture Hauntings on The Jetsons Stefano Morello The Graduate Center, City University of New York [email protected] From Back to the Future to The Wonder Years, from Peggy Sue Got Married to The Stray Cats’ records – 1980s youth culture abounds with what Michael D. Dwyer has called “pop nostalgia,” a set of critical affective responses to representations of previous eras used to remake the present or to imagine corrective alternatives to it. Longings for the Fifties, Dwyer observes, were especially key to America’s self-fashioning during the Reagan era (2015). Moving from these premises, I turn to anachronisms, aesthetic resonances, and intertextual references that point to, as Mark Fisher would have it, both a lost past and lost futures (Fisher 2014, 2-29) in the episodes of the Hanna-Barbera animated series The Jetsons produced for syndication between 1985 and 1987. A product of Cold War discourse and the early days of the Space Age, the series is characterized by a bidirectional rhetoric: if its setting emphasizes the empowering and alienating effects of technological advancement, its characters and its retrofuture aesthetics root the show in a recognizable and desirable all-American past. -

French Animation History Ebook

FRENCH ANIMATION HISTORY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Richard Neupert | 224 pages | 03 Mar 2014 | John Wiley & Sons Inc | 9781118798768 | English | New York, United States French Animation History PDF Book Messmer directed and animated more than Felix cartoons in the years through This article needs additional citations for verification. The Betty Boop cartoons were stripped of sexual innuendo and her skimpy dresses, and she became more family-friendly. A French-language version was released in Mittens the railway cat blissfully wanders around a model train set. Mat marked it as to-read Sep 05, Just a moment while we sign you in to your Goodreads account. In , Max Fleischer invented the rotoscope patented in to streamline the frame-by-frame copying process - it was a device used to overlay drawings on live-action film. First Animated Feature: The little-known but pioneering, oldest-surviving feature-length animated film that can be verified with puppet, paper cut-out silhouette animation techniques and color tinting was released by German film-maker and avante-garde artist Lotte Reiniger, The Adventures of Prince Achmed aka Die Abenteuer des Prinzen Achmed , Germ. Books 10 Acclaimed French-Canadian Writers. Rating details. Dave and Max Fleischer, in an agreement with Paramount and DC Comics, also produced a series of seventeen expensive Superman cartoons in the early s. Box Office Mojo. The songs in the series ranged from contemporary tunes to old-time favorites. He goes with his fox terrier Milou to the waterfront to look for a story, and finds an old merchant ship named the Karaboudjan. The Fleischers launched a new series from to called Talkartoons that featured their smart-talking, singing dog-like character named Bimbo. -

Humanoid Robots Are Perceived As an Evolutionary Threat

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.13.456053; this version posted August 13, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Humanoid robots are perceived as an evolutionary threat Zhengde Wei1, +, Ying Chen 2, +, Jiecheng Ren1, Yi Piao1, Pengyu Zhang1, Rujing Zha1, Bensheng Qiu3, Daren Zhang1, Yanchao Bi4, Shihui Han5, Chunbo Li6 *, Xiaochu Zhang1, 2, 3, 7 * 1 Hefei National Laboratory for Physical Sciences at the Microscale and School of Life Sciences, Division of Life Science and Medicine, University of Science & Technology of China, Hefei, Anhui 230027, China 2 School of Humanities & Social Science, University of Science & Technology of China, Hefei, Anhui 230026, China 3 Centers for Biomedical Engineering, School of Information Science and Technology, University of Science & Technology of China, Hefei, Anhui 230027, China 4 State Key Laboratory of Cognitive Neuroscience and Learning, Beijing Normal University, Beijing 100875, China 5 School of Psychological and Cognitive Sciences, Peking University, Beijing, China 6 Shanghai Key Laboratory of Psychotic Disorders, Shanghai Mental Health Center, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai 200030, China 7 Academy of Psychology and Behavior, Tianjin Normal University, Tianjin, 300387, China + These authors contributed equally to this work Correspondence: [email protected]; [email protected] 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.13.456053; this version posted August 13, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

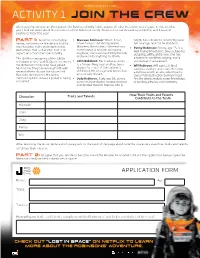

ACTIVITY 1 Join the Crew

REPRODUCIBLE ACTIVITY ACTIVITY 1 Join the Crew After crash-landing on an alien planet, the Robinson family fights against all odds to survive and escape. In this activity, you’ll find out more about the members of the Robinson family. Season 1 is now streaming on Netflix, and Season 2 premieres later this year. Part 1: Read the information • Maureen Robinson: Smart, brave, bright, has a desire to constantly prove below, and then use the details to fill in adventurous, and strong-willed, her courage, and can be stubborn. the character traits and talents table. Maureen, the mother, is the mission • Penny Robinson: Penny, age 15, is a Remember that a character trait is an commander. A brilliant aerospace well-trained mechanic. She is cheerful, aspect of a character’s personality. engineer, she loves her family fiercely outgoing, witty, and brave. She has and would do anything for them. The Netflix reimagining of the 1960s a talent for problem-solving, and is television series “Lost in Space” features • John Robinson: Her husband, John, somewhat of a daredevil. the Robinson family who have joined is a former Navy Seal and has been • Will Robinson: Will, age 11, is kind, Mission 24. They are leaving Earth with absent for much of the children’s cautious, creative, and smart. He forms several others aboard the spacecraft childhood. He is tough and smart, but a tight bond with an alien robot that he Resolute destined for the Alpha emotionally distant. saves from destruction during a forest Centauri system, where a planet is being • Judy Robinson: Judy, age 18, serves fire. -

Valkyrie: NASA's First Bipedal Humanoid Robot

Valkyrie: NASA's First Bipedal Humanoid Robot Nicolaus A. Radford, Philip Strawser, Kimberly Hambuchen, Joshua S. Mehling, William K. Verdeyen, Stuart Donnan, James Holley, Jairo Sanchez, Vienny Nguyen, Lyndon Bridgwater, Reginald Berka, Robert Ambrose∗ NASA Johnson Space Center Christopher McQuin NASA Jet Propulsion Lab John D. Yamokoski Stephen Hart, Raymond Guo Institute of Human Machine Cognition General Motors Adam Parsons, Brian Wightman, Paul Dinh, Barrett Ames, Charles Blakely, Courtney Edmonson, Brett Sommers, Rochelle Rea, Chad Tobler, Heather Bibby Oceaneering Space Systems Brice Howard, Lei Nui, Andrew Lee, David Chesney Robert Platt Jr. Michael Conover, Lily Truong Wyle Laboratories Northeastern University Jacobs Engineering Gwendolyn Johnson, Chien-Liang Fok, Eric Cousineau, Ryan Sinnet, Nicholas Paine, Luis Sentis Jordan Lack, Matthew Powell, University of Texas Austin Benjamin Morris, Aaron Ames Texas A&M University ∗Due to the large number of contributors toward this work, email addresses and physical addresses have been omitted. Please contact Kris Verdeyen from NASA-JSC at [email protected] with any inquiries. Abstract In December 2013, sixteen teams from around the world gathered at Homestead Speedway near Miami, FL to participate in the DARPA Robotics Challenge (DRC) Trials, an aggressive robotics competition, partly inspired by the aftermath of the Fukushima Daiichi reactor incident. While the focus of the DRC Trials is to advance robotics for use in austere and inhospitable environments, the objectives of the DRC are to progress the areas of supervised autonomy and mobile manipulation for everyday robotics. NASA's Johnson Space Center led a team comprised of numerous partners to develop Valkyrie, NASA's first bipedal humanoid robot. -

Rio Content Market 2015 Newsletter

Rio Content Market 2015 Newsletter > 5 ANCIENT HISTORY > 6 GREAT MYTHS (THE) AUTHOR Tales of love, sex, power, betrayal, heinous crimes, unbearable François BUSNEL DIRECTOR separations, atrocious revenge, and metamorphoses - the poetic François BUSNEL force of the myths has crossed the centuries. COPRODUCERS ARTE FRANCE, ROSEBUD PRODUCTIONS "The Great Myths" documentary series sets out to recount these ancient stories using FORMAT animations created especially for the occasion, and illustrations chosen from the entire 20 x 26 ', 2015 history of art. This dynamic blend, a bridge between modernity and history, ancient AVAILABLE RIGHTS TV - DVD - VOD - Non-theatrical rights - narrative and contemporary dramatic art, is a new way to discover or re-discover this part Internet of our universal heritage. VERSIONS English - German - French TERRITORY(IES) PREVISIONAL DELIVERY: NOVEMBER 2015 Worldwide. Episodes : THESEUS - ORPHEUS - PERSEUS - MEDEA - APOLLO - PROMETHEUS - OEDIPUS - DIONYSUS - HADES - ANTIGONE - ZEUS - ATHENA - ICARUS - CHIRON - HERA - APHRODITE - HERCULES - HERMES - BELLEROPHON - EROS. CONTEMPORARY HISTORY > 7 ACTION T4: A DOCTOR UNDER NAZISM DIRECTOR This documentary recounts his story and through the man's story, Catherine BERNSTEIN COPRODUCER that of the so-called "Action T4", which consisted of eliminating ZADIG PRODUCTIONS physical and mental disabilities and those people considered by the FORMAT Nazi regime to be useless or "asocial". 1 x 52 ', 2014 AVAILABLE RIGHTS Doctor Julius Hallervorden, a major name in the science of brain pathology, first benefited TV - DVD - VOD - Non-theatrical rights - from, then contributed to the systematic assassination ordered by Hitler of German Internet mentally ill persons, by recovering the brains of 690 victims. He nevertheless pursued a VERSIONS English - French brilliant post-war career, in all impunity, and died covered in honours. -

Lost-In-Space Teacher Book

Sadako and the The History of Cole, the Outback Disaster around the Food Chains Lost in English Lost in Space Window to the Past Thousand Cranes Bread Giant Indian Ocean and Webs Book c Level 30 Level 30 Text TypeText Narrative (Science Fiction) Word CountWord 959 High-Frequency Word/s Introduced Word/s We have designed these lesson plans so that you can have the plan in front of you as you teach, along with a copy of the book. Suggestions for teaching have been divided into questions and discussion that you may have with the students before, during, and after they read. However, you may prefer to explore the meaning and language in more detail before the students read. Your decisions will depend on the gap between the students’ current knowledge and the content, vocabulary, and language of the book they are about to read. The more information the students have up front, the easier it will be for them to read the text. However, this does not mean that you should read the text to them first. We have addressed four areas we think are important in developing good readers. As well as comprehension and decoding, we have addressed the issue of the students being able to analyse and use texts they read. The symbols below guide you to the type of question or discussion. This symbol relates to decoding (code breaker) This symbol relates to use (text user) This symbol relates to comprehension (meaning maker) This symbol relates to critical analysis (text critic or analyser) Have the students read the title and the names of the author and illustrator on the front cover. -

The Significant Other: a Literary History of Elves

1616796596 The Significant Other: a Literary History of Elves By Jenni Bergman Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Cardiff School of English, Communication and Philosophy Cardiff University 2011 UMI Number: U516593 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U516593 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not concurrently submitted on candidature for any degree. Signed .(candidate) Date. STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD. (candidate) Date. STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. Signed. (candidate) Date. 3/A W/ STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed (candidate) Date. STATEMENT 4 - BAR ON ACCESS APPROVED I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan after expiry of a bar on accessapproved bv the Graduate Development Committee.