Open Tsang-Ikementhesis.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

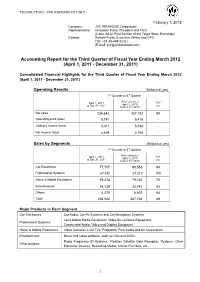

Accounting Report for the Third Quarter of Fiscal Year Ending March 2012 (April 1, 2011 - December 31, 2011)

TRANSLATION - FOR REFERENCE ONLY - February 1, 2012 Company: JVC KENWOOD Corporation Representative: Hisayoshi Fuwa, President and CEO (Code: 6632; First Section of the Tokyo Stock Exchange) Contact: Satoshi Fujita, Executive Officer and CFO (Tel: +81-45-444-5232) (E-mail: [email protected]) Accounting Report for the Third Quarter of Fiscal Year Ending March 2012 (April 1, 2011 - December 31, 2011) Consolidated Financial Highlights for the Third Quarter of Fiscal Year Ending March 2012 (April 1, 2011 - December 31, 2011) Operating Results (Millions of yen) 1st Quarter to 3rd Quarter (For reference) April 1, 2011 YoY April 1, 2010 to Dec.31, 2011 to Dec.31, 2010 (%) Net sales 236,542 267,182 89 Operating profit (loss) 8,791 9,416 - Ordinary income (loss) 6,511 6,530 - Net income (loss) 4,409 2,193 - Sales by Segments (Millions of yen) 1st Quarter to 3rd Quarter (For reference) YoY April 1, 2011 April 1, 2010 to Dec.31, 2011 to Dec.31, 2010 (%) Car Electronics 77,707 80,558 96 Professional Systems 67,142 67,210 100 Home & Mobile Electronics 59,274 79,167 75 Entertainment 28,139 33,742 83 Others 4,279 6,502 66 Total 236,542 267,182 89 Major Products in Each Segment Car Electronics Car Audio, Car AV Systems and Car Navigation Systems Land Mobile Radio Equipment, Video Surveillance Equipment, Professional Systems Commercial Audio, Video and Display Equipment Home & Mobile Electronics Video Cameras, LCD TVs, Projectors, Pure Audio and AV Accessories Entertainment Music and video software, such as CDs and DVDs Radio Frequency ID Systems, Weather Satellite Data Reception Systems, Other Other projects Electronic Devices, Recording Media, Interior Furniture, etc. -

Shinzo Abe George W

Shinzo Abe George W. Bush Ichiro Suzuki DOB: 21 st Sep 1954 DOB: 6 th July 1946 DOB: 22 nd October 1973 Age: Age: Age: . m 1.80m 1.75m Yamaguchi USA Aichi Hideki Matsui Shinji Ono Bae Yong Joon DOB: 12 th June 1974 DOB: 27 th September 1979 DOB: 29 th August 1972 Age: Age: Age: 1.82 1.75 1.80 Ishikawa Shizuoka South Korea David Beckham Shunsuke Nakamura Bob Sapp DOB: 2 nd May 1974 DOB: 24 th June 1978 DOB: 22 nd September 1974 Age: Age: Age: 1.80 1.78 2.00 England Yokohama USA Ryoko Tani Kosuke Kitajima Mino Monta DOB: 6 th September 1975 DOB: 22 nd September 1982 DOB: 22 nd August 1944 Age: Age: Age: 1.46 1.78 1.65 Fukuoka Tokyo Tokyo Hidetoshi Nakata Osama Bin Laden Masami Hisamoto DOB: 22 nd January 1977 DOB: 10 th March 1957 DOB: 8 th July 1960 Age: Age: Age: 1.75 1.95 1.54 Yamanashi Saudi Arabia Osaka Nanako Matsushima Takuya Kimura Shingo Katori DOB: 13 th October 1973 DOB: 13 th November 1972 DOB: 31 st January 1977 Age: Age: Age: 1.70 1.75 1.83 Kanagawa Tokyo Yokohama Tsuyoshi Kusanagi Goro Inagaki Masahiro Nakai DOB: 9th July 1974 DOB: 8 th December 1973 DOB: 18 th August 1972 Age: Age: Age: 1.70 1.76 1.65 Ehime Tokyo Kanagawa Takeshi Kitano Akiko Wada Yao Ming ( ヤオミン) DOB: 18 th January 1947 DOB: April 10 th 1950 DOB: 12 th September 1980 Age: Age: Age: 1.85 1m74 2.29 Tokyo Osaka China Shaquille O’Neal Ai Fukuhara Naoko Takahashi DOB: March 6 th 1972 DOB: 1 st November 1988 DOB: 6 th May 1972 Age: Age: Age: 2m16 154 162 USA Miyagi Gifu Sanma Akashiya Saburo Kitajima Hikaru Utada DOB: 1 st July 1955 DOB: 4 th October 1936 DOB: -

This Project by Patricia J

TEACHING ADULT EFL LEARNERS IN JAPAN FROM A JAPANESE PERSPECTIVE SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE MASTER OF ARTS IN TEACHING DEGREE AT THE SCHOOL FOR INTERNATIONAL TRAINING BRATTLEBORO, VERMONT BY PATRICIA JEAN GAGE SEPTEMBER 2004 © PATRICIA JEAN GAGE 2004 This project by Patricia J. Gage is accepted in its present form. The author hereby grants the School for International Training the permission to electronically reproduce and transmit this document to the students, alumni, staff, and faculty of the World Learning Community. © Patricia Jean Gage, 2004. All rights reserved. Date _________________________________ Project Advisor _________________________________ (Paul LeVasseur) Project Reader _________________________________ (Kevin O’Donnell) Acknowledgements There are so many people that contributed to this project and without their help this project would not have been possible. First, I would like to thank my Sakae and Taiyonomachi classes for always being patient with me and for taking time out of their busy schedules to write feedback about each of the topics. Second, I am very grateful to Toshihiko Kamegaya, Mayumi Noda, Katsuko Usui, Terukazu Chinen and Naoko Ueda for providing the anecdotes in the section titled “Voices from Japan.” Third, I would like to give a special thanks to Paul LeVasseur, my advisor and teacher, whose Four Skills class inspired me to do this project and whose insightful comments about this paper were invaluable. I would also like to thank the summer faculty at SIT for their dedication and commitment to the teaching profession and to their students. Next, I would like to acknowledge my reader, Kevin O’Donnell, for guiding me in the right direction and for spending time, in his already hectic schedule, to read my paper. -

Idols and Celebrity in Japanese Media Culture, Edited by Patrick W

Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Murdoch University - PalgraveConnect - 2013-08-20 - PalgraveConnect University - licensed to Murdoch www.palgraveconnect.com material from Copyright 10.1057/9781137283788 - Idols and Celebrity in Japanese Media Culture, Edited by Patrick W. Galbraith and Jason G. Karlin Idols and Celebrity in Japanese Media Culture Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Murdoch University - PalgraveConnect - 2013-08-20 - PalgraveConnect University - licensed to Murdoch www.palgraveconnect.com material from Copyright 10.1057/9781137283788 - Idols and Celebrity in Japanese Media Culture, Edited by Patrick W. Galbraith and Jason G. Karlin This page intentionally left blank Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Murdoch University - PalgraveConnect - 2013-08-20 - PalgraveConnect University - licensed to Murdoch www.palgraveconnect.com material from Copyright 10.1057/9781137283788 - Idols and Celebrity in Japanese Media Culture, Edited by Patrick W. Galbraith and Jason G. Karlin Idols and Celebrity in Japanese Media Culture Edited by Patrick W. Galbraith and Jason G. Karlin University of Tokyo, Japan Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Murdoch University - PalgraveConnect - 2013-08-20 - PalgraveConnect University - licensed to Murdoch www.palgraveconnect.com material from Copyright 10.1057/9781137283788 - Idols and Celebrity in Japanese Media Culture, Edited by Patrick W. Galbraith and Jason G. Karlin Introduction, selection -

Viu Acquires Exclusive OTT Rights to 12 Iconic Takuya Kimura Dramas

Viu acquires exclusive OTT rights to 12 iconic Takuya Kimura dramas For the first time, Fuji TV releases timeless masterpieces Long Vacation, Love Generation, Hero series, among others, on an OTT Platform PCCW (SEHK:0008) – HONG KONG / SINGAPORE / INDONESIA / MALAYSIA, July 22, 2020 – Viu, a leading pan-regional OTT video service from PCCW Media Group, today announced that it has acquired exclusive OTT rights from Fuji TV to bring 12 iconic Takuya Kimura titles, including Long Vacation, Love Generation, and the Hero series to Viu-ers. Both a successful singer and actor, Takuya Kimura (also known as Kimutaku) is an iconic figure in the Japanese entertainment industry. He was a member of the best-selling boy band in Asia, SMAP, which hosted the widely acclaimed variety show SMAP x SMAP that was on air for 20 years. After the massively successful drama series Long Vacation starring Takuya Kimura, his popularity was propelled to a new level and the record ratings of his subsequent drama series earned him the title of “The King of Ratings”. The Japanese heartthrob has legions of fans across Hong Kong, Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand and the Philippines. Ms. Virginia Lim, Chief Content Officer of Viu, said, "Our commitment is to bring the best Asian content to our audiences, and without question, Takuya Kimura’s dramatic works fit that definition perfectly. We are very excited to be the first and only^ OTT platform offering these beloved titles to the viewers. The fans of Takuya Kimura will now get to watch his engaging and charming drama series on Viu at their leisure. -

Universidade De Brasília Instituto De Letras Departamento De Línguas Estrangeiras E Tradução Licenciatura Em Língua E Literatura Japonesa

UNIVERSIDADE DE BRASÍLIA INSTITUTO DE LETRAS DEPARTAMENTO DE LÍNGUAS ESTRANGEIRAS E TRADUÇÃO LICENCIATURA EM LÍNGUA E LITERATURA JAPONESA DÉBORA HABIB VIEIRA DA SILVA A AFETIVIDADE E O DISTANCIAMENTO NO RELACIONAMENTO ÍDOLO-FÃ: Um Estudo de Caso Realizado com Ex-fãs da Johnny's & Associates BRASÍLIA 2015 UNIVERSIDADE DE BRASÍLIA INSTITUTO DE LETRAS DEPARTAMENTO DE LÍNGUAS ESTRANGEIRAS E TRADUÇÃO LICENCIATURA EM LÍNGUA E LITERATURA JAPONESA DÉBORA HABIB VIEIRA DA SILVA A AFETIVIDADE E O DISTANCIAMENTO NO RELACIONAMENTO ÍDOLO-FÃ: Um Estudo de Caso Realizado com Ex-fãs da Johnny's & Associates Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso apresentado ao Curso de Licenciatura em Língua e Literatura Japonesa da Universidade de Brasília (UnB), como requisito para obtenção do diploma de graduado em Língua e Literatura Japonesa. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Ronan Alves Pereira BRASÍLIA 2015 [ii] UNIVERSIDADE DE BRASÍLIA DÉBORA HABIB VIEIRA DA SILVA A AFETIVIDADE E O DISTANCIAMENTO NO RELACIONAMENTO ÍDOLO-FÃ: Um Estudo de Caso Realizado com Ex-fãs da Johnny's & Associates Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso apresentado ao Curso de Licenciatura em Língua e Literatura Japonesa da Universidade de Brasília (UnB), como requisito para obtenção do diploma de graduado em Língua e Literatura Japonesa. Aprovado com “Louvor e Distinção” em 19 de junho de 15. BANCA EXAMINADORA __________________________________ Prof. Dr. Ronan Pereira Alves (Orientador) __________________________________ Profa. Dra. Tae Suzuki __________________________________ Prof. Lic. Gabriel de Oliveira Fernandes BRASÍLIA- DF 2015 [iii] AGRADECIMENTOS Agradeço primeiramente a Deus pelo dom de minha vida e por me capacitar com a faculdade da inteligência e a perseverança para escrever minha própria história. Em segundo lugar, gostaria de agradecer a meu pai Belmiro e minha mãe Ivone, por me educarem e por terem me dado a oportunidade de receber um ensino de qualidade, sem o qual esta graduação jamais se faria possível. -

クリスマスソング Back Number 旅立ちの唄 Mr.Children Kinki Kids あの紙ヒコーキくもり空わって 19 く る み Mr.Children 抱きしめたい Mr.Children ま 負けないで ZARD

JJJ J-POP・歌謡曲 JJJ J-POP・歌謡曲 JJJ J-POP・歌謡曲 JJJ J-POP・歌謡曲 あ 愛 唄 GReeeeN キ セ キ GReeeeN ⻘春アミーゴ 修二と彰 遥 か GReeeeN 美空ひばり 財津和夫 愛 燦 燦 小椋 佳 君がいるだけで 米米クラブ ⻘ 春 の 影 チューリップ パプリカ Foorin 会いたくて会いたくて ⻄野カナ 君 が 好 き Mr.Children 世界に一つだけの花 SMAP ひこうき雲 秦 基博 愛にできることはまだあるかい 天気の子 君って… ⻄野カナ 背中越しのチャンス ⻲と山P ひまわりの約束 荒井由 愛 で し た 関ジャニ∞ 君に出会えたから miwa 戦場のメリ ークリスマス 坂本龍一 ビリーブ Believe 嵐 ファースト ラブ 愛 は 勝 つ KAN 君をさがしてた CHEMISTRY 千の風になって 秋川雅史 First Love 宇多田ヒカル A・RA ・SHI キャンユーセレブレイト 千本桜 feat .初音ミク 大塚 愛 ア ラ シ 嵐 CAN YOU CELEBRAT E? 安室奈美恵 千 ⿊うさ P feat 初音ミク プラネタリウム アイ ラブ ユー 小田和正 スキマスイッチ official髭男dism I LOVE YOU 尾崎 豊 今日もどこかで 全 力 少 年 プリテンダー 荒井由実 愛をこめて花束をSuperfly キ ラ キ ラ 小田和正 卒 業 写 真 ハイ・ファイ・セット ブルーバード いきものがかり ギブ ミー ラブ ベスト フレンド 赤いスイートピー 松田聖子 Give Me Love Hey! Say! JUMP 空も飛べるはず スピッツ Best Fr iend Kiroro 明日晴れるかな 桑田佳祐 クリスマスイブ 山下達郎 た ただ…逢いたくて EXILE 星影のエール GReeeeN ボクの背中には羽根がある 明日への扉 I WiSH クリスマスソング back number 旅立ちの唄 Mr.Children Kinki Kids あの紙ヒコーキくもり空わって 19 く る み Mr.Children 抱きしめたい Mr.Children ま 負けないで ZARD ありがとう いきものがかり 決意の朝に Aqua Timez チ ェ リ ー スピッツ まちがいさがし 菅田将暉 official 髭男 dism 竹内まりや サザン I LOVE … CHE.R.RY YUI アイラブ… 元気を出して 島谷ひとみ チェリー 真夏の果実 オール スターズ 谷村新司 いい日旅立ち 山口百恵 恋 星野 源 地 上 の 星 中島みゆき 守ってあげたい 松任谷由実 行くぜっ ! 怪盗少 女 恋するフォーチュンクッキー ツ ナ ミ あいみょん ももいろクローバー 恋 AKB48 TSUNAMI サザン オール スター ズ マリーゴールド 見上げてごらん夜の星を ー B’z 松任谷 由実 赤い鳥 いつかのメリ クリスマス 恋人がサンタクロース 翼をください 平井 堅・堂本 剛・坂本 九 さだまさし 糸 中島みゆき 秋 桜コスモス 山口百恵 蕾つぼみ コブクロ 三 日 月 絢 香 サザン 小田和正 手 紙 〜拝啓⼗五の君へ〜 いとしのエリー オール スターズ 言葉にできない オフコース アンジェラ アキ 見たこともない景色 菅田将暉 イノセント ワールド innocent world Mr.Children 粉 雪 レミオロメン 天 体 観 測 BUMP OF CHICKEN 道 EXILE 浦島太郎 (桐谷健太) Sign トゥモロー 未来予想図Ⅱ 海 -

The “Pop Pacific” Japanese-American Sojourners and the Development of Japanese Popular Music

The “Pop Pacific” Japanese-American Sojourners and the Development of Japanese Popular Music By Jayson Makoto Chun The year 2013 proved a record-setting year in Japanese popular music. The male idol group Arashi occupied the spot for the top-selling album for the fourth year in a row, matching the record set by female singer Utada Hikaru. Arashi, managed by Johnny & Associates, a talent management agency specializing in male idol groups, also occupied the top spot for artist total sales while seven of the top twenty-five singles (and twenty of the top fifty) that year also came from Johnny & Associates groups (Oricon 2013b).1 With Japan as the world’s second largest music market at US$3.01 billion in sales in 2013, trailing only the United States (RIAJ 2014), this talent management agency has been one of the most profitable in the world. Across several decades, Johnny Hiromu Kitagawa (born 1931), the brains behind this agency, produced more than 232 chart-topping singles from forty acts and 8,419 concerts (between 2010 and 2012), the most by any individual in history, according to Guinness World Records, which presented two awards to Kitagawa in 2010 (Schwartz 2013), and a third award for the most number-one acts (thirty-five) produced by an individual (Guinness World Record News 2012). Beginning with the debut album of his first group, Johnnys in 1964, Kitagawa has presided over a hit-making factory. One should also look at R&B (Rhythm and Blues) singer Utada Hikaru (born 1983), whose record of four number one albums of the year Arashi matched. -

Johnny's” Entertainers Omnipresent on Japanese TV: Postwar Media and the Postwar Family

CULTURE The “Johnny's” Entertainers Omnipresent on Japanese TV: Postwar Media and the Postwar Family Shuto Yoshiki, Associate Professor, Nippon Sports and Science University Introduction What do Japanese people think of when they hear the name Johnnies? Perhaps pop groups such as SMAP or Arashi that belong to the Johnny & Associates talent agency? Or perhaps the title of specific TV programs or movies? If they are not that interested, perhaps they will be reminded of the words “beautiful young boys” or “scandal”? On the other hand, if they are well-informed about the topic perhaps jargon terms such as “oriki ,” “doutan ,” or “shinmechu ” are second nature? In this way the word “Johnnies” (the casual name given to groups managed by Johnny & Associates) is likely to evoke all sorts of images. But one thing is sure: almost no Japanese person would reply that they hadn’t heard the name. If a person lives within Japanese society and they watch television even just a little, whether they like it or not they will come across Johnnies. The performing artists managed by Johnny & Associates appear on television almost every hour of the viewing day, and they feature in all kinds of TV programs: music, drama, entertainment, news, live sports, education, and cooking. In Japanese society Johnnies are consumed as a matter of course and without need for explanation. They make up part of the background of everyday life. The Johnnies were created in April 1962. That year, a group called “Johnnys” was put together composed of Aoi Teruhiko, Nakatani Ryo, Iino Osami, and Maie Hiromi. -

HAWAIIAN CAUSATIVE-SIMULATIVE PREFIXES AS TRANSITIVITY and SEMANTIC CONVERSION AFFIXES Plan B Paper by Matthew Brittain in Parti

HAWAIIAN CAUSATIVE-SIMULATIVE PREFIXES AS TRANSITIVITY AND SEMANTIC CONVERSION AFFIXES Plan B Paper By Matthew Brittain In Partial Fulfillment of the requirements for Master of Arts 4/93 University of Hawai~i at Manoa School of Hawaiian, Asian and Pacific Islands Studies Center for Pacific Islands Studies Dr. George Grace Dr. Emily Hawkins Dr. Robert Kiste HAWAIIAN CONVERSION PREFIXES 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ............•.........•...............•....p. 3 Abstract p. 4 Introduction p. 4 Disclaimer p. 5 Definition of Terms p. 8 Importance of Transitivity in Conversion Prefixes......•...p. 14 Cross-Referencing System For MUltiple Meanings•............p. 21 Method..•...........•.........•.....•..........•..•.....•..p . 24 Forms of Hawaiian Conversion prefixes........•.........•...p. 25 Discussion of Relevent Literature...................•.•....p. 29 Results p. 31 causative Conversion Hawaiian Prefix Data p. 34 Similitude Conversion Hawaiian Prefix Data p. 43 Quality Conversion Hawaiian Prefix Data•...................p. 45 Provision of Noun Hawaiian Prefix Data.........•....•.•....p. 53 Simple Transitivity Conversion Hawaiian Prefix Data•.....•.p. 54 No Change Hawaiian Prefix Data........................•....p. 57 Items with Double Conversion Hawaiian Prefix Data....•.....p. 66 Bibliography p. 68 2 CROSS-REFERENCE GUIDE FOR ITEMS WITH MULTIPLE MEANINGS •...•.Refer to causative conversion section...........p. 34 ••..••Refer to similitude conversion section..........p. 43 T •••••Refer to quality conversion section.............p. 45 €e •••••Refer to provision of noun conversion section, •.p. 53 0 .....Refer to simple conversion section.............p. 54 *.....Refer to no change section......................p. 57 o .....Refer to double conversion section..............p. 66 ho'onohonoho i Waineki kauhale 0 Limaloa. Set in order at Waineki are the houses of Limaloa. Limaloa, the god of mirages, made houses appear and disappear on the plains of Mana. -

Masculinities in Japan

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI Filozofická fakulta Katedra ázijských štúdií MAGISTERSKÁ DIPLOMOVÁ PRÁCA Masculinities in Japan Discovering the shifting gender boundaries of contemporary Japan OLOMOUC 2014, Barbara Németh, Bc. vedúci diplomovej práce: Mgr. Ivona Barešová, Ph.D. Prehlasujem, že som diplomovú prácu vypracovala samostatne a uviedla všetky použité zdroje a literatúru. V Olomouci, dňa 6. 5. 2014 Podpis Anotácia Autor Barbara Németh Katedra a fakulta Katedra ázijských štúdií, Filozofická fakulta Názov práce Masculinities in Japan - Discovering the shifting gender boundaries of contemporary Japan Vedúcí diplomovej práce Mgr. Ivona Barešová, Ph.D. Jazyk diplomovej práce angličtina Počet strán (znakov) 78 (117026) Počet použitých zdrojov 52 Kľúčové slova Japonsko, maskulinita, genderové problémy, sōshokukei danshi, japonská mládež, salaryman Abstrakt Cieľom tejto práce je opísať meniace sa ideály maskulinity za posledných približne tridsať rokov. Za túto dobu sa v Japonsku udialo niekoľko ekonomických ako aj spoločenských zmien, ktoré so sebou priniesli nový pohľad na postavenie mužov v spoločnosti a otvorili priestor pre vznik a šírenie nových foriem maskulinity - predstavovateľmi ktorých sú predovšetkým mladí Japonci vo vekovej skupine 18 az 26 rokov. V rámci práce sa preto zameriam na starší ideál maskulinity, dominantný predovšetkým po Druhej svetovej vojne, ale významný dodnes. V ďalších kapitolách opíšem meniace sa ideály, ktoré predstavujú mladšie generácie Japoncov, ako aj reakciu starších kritikov a masmédií na niektoré z týchto fenoménov. Ďakujem vedúcej práce Mgr. Ivone Barešovej Ph.D., za jej trpezlivosť, ochotu a pomoc pri stanovovaní témy práce. Taktiež ďakujem svojej rodine a priateľom za ich podporu, bez ktorej by táto práca nemohla existovať. Table of Contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 7 1.1. -

Remote Sensing of the Terrestrial Water Cycle Kona, Hawaii, USA 19 –22 February 2012

AGU Chapman Conference on Remote Sensing of the Terrestrial Water Cycle Kona, Hawaii, USA 19 –22 February 2012 Conveners Venkat Lakshmi, University of South Carolina, USA Doug Alsdorf, Ohio State University, USA Jared Entin, NASA, USA George Huffman, NASA, USA Peter van Oevelen, GEWEX, USA Juraj Parajka, Vienna University of Technology Program Committee Bill Kustas, USDA-ARS Bob Adler, University of Maryland Chris Rudiger, Monash University Jay Famiglietti, University of California, Irvine, USA Martha Anderson, USDA, USA Matt Rodell, NASA, USA Michael Cosh, USDA, USA Steve Running, University of Montana Co-Sponsor The conference organizers acknowledge the generous support of the following organizations: 2 AGU Chapman Conference on Remote Sensing of the Terrestrial Water Cycle Meeting At A Glance Sunday, 19 February 2012 1500h – 2100h Registration 1700h – 1710h Welcome Remarks 1710h – 1750h Keynote Speaker – Andrew C. Revkin, The New York Times 1750h – 1900h Ice Breaker Reception 1900h Dinner on Your Own Monday, 20 February 2012 800h – 1000h Oral Session 1: Current Challenges in Terrestrial Hydrology 1000h – 1030h Coffee Break and Networking Break 1030h – 1200h Breakout Sessions - Variables Observed by Satellite Remote Sensing Evapotranspiration Soil Moisture Snow Surface Water Groundwater Precipitation 1200h – 1330h Lunch on Your Own 1330h – 1600h Oral Session 2: Estimating Water Storage Components: Surface Water, Groundwater, and Ice/Snow 1600h – 1630h Coffee Break 1630h – 1900h Poster Session I and Ice Breaker 1900h Dinner on Your Own