Jay Z and Kanye West

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Language Arts Thematic Textual Analysis

HIP-HOPLANGUAGE ARTS THEMATIC TEXTUAL ANALYSIS Michael Cirelli and Alan Sitomer The Classics The Contemporaries Mark Twain Jay-Z Aristotle Lauryn Hill Frederick Douglass Nas Jane Austen Kendrick Lamar Oliver Wendell Holmes Tupac Shakur Martin Luther King Jr. Drake Gandhi Afrika Bambaataa The U.S. Constitution Chuck D Philip Vera Cruz Queen Latifah Lao-tzu Jeff Chang Alice Walker Lupe Fiasco Ernest Hemingway Rakim Sonia Sotomayor J. Cole Junot Díaz Eminem Delivering the 5th Element of Hip-Hop to Capable Young Minds 1. B-boying 2. MC-ing 3. Graffiti Art 4. DJ-ing 5. Knowledge Note: All work contained herein begins with the smart and effective implementation of standards-based lesson plans that have been constructed around three principles: 1. no profanity 2. no misogyny 3. no homophobia Great vocabulary words to discuss; inappropriate elements to validate in a classroom environment. HipHopLanguageArts3.indd 1 06/03/2015 15:38:37 2 | READ CLOSELY HIP-HOP INTERPRETATION GUIDE Question: Is violence ever an appropriate solution for resolving conflict? Consider the following text: from “Murder to Excellence” by Kanye West (with Jay-Z) I’m from the murder capital, where they murder for capital Heard about at least 3 killings this afternoon Lookin’ at the news like dang I was just with him after school, No shop class but half the school got a tool, And I could die any day type attitude Plus his little brother got shot reppin’ his avenue It’s time for us to stop and re-define black power 41 souls murdered in 50 hours 1. -

Jay-Z: in Tha’ Mix

ASC 1138--JAY-Z: IN THA’ MIX JAY-Z: IN THA’ MIX CREDIT HOURS Leta Hendricks [email protected] Tel: 614-688-7478 Classroom – Room 150A Thompson Library Class Meeting – Fridays – 1:30 – 2:18 p.m. January 11 – April 19, 2013 Office Hours – Tuesday – 9:00 – 11:00 a.m. and by appointment WEB Site – Twitter – Second Life- Hip Hop Underground http://slurl.com/secondlife/Cybrary%20City%20II/77/198/8 SYLLABUS COURSE DESCRIPTION JAY-Z is an entrepreneurial phenomenon of the last the twenty years. This seminar examines JAY-Z from different perspectives as an artist and as a businessman. The seminar will discuss perspectives and beliefs about rap music and popular culture. JAY-Z is currently one of the most influential iconic figures of Global Pop Culture. His music embodies the quintessentially “African American” genre of music, we will study his musical roots, trace the development of his career and connect JAY-Z with his culture. An analysis of his business empire will include his drug-marked youth, musical achievements, and urban-informed business savvy. The Seminar will discuss his lyrics and their meanings which reveal JAY-Z’s art and life. JAY-Z heavily borrows from American musical and literary traditions through an examination of select recordings, autobiography, film, essays and criticism, this Seminar will provide students the opportunity to discover the significance of JAY-Z’s contributions to lyric writing, popular music, and beyond. The following resources will facilitate students learning development by using multiple content formats. DJ Hero will engage students through gameplay, simulating DJ turntablism (mixing styles and techniques) connecting gaming activities to assignments, discussions, and projects on JAY-Z and current Rap artists. -

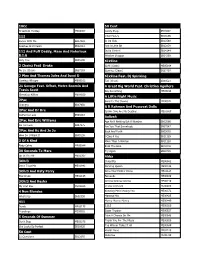

Karaoke Song List

10Cc 50 Cent Dreadlock Holiday MX00002 Candy Shop SB13602 112 I Got Money SB16596 Dance With Me SB17659 In Da Club SB12588 Peaches And Cream SB12012 Just A Little Bit SB13839 112 And Puff Daddy, Mase And Notorious Outta Control SB14144 B.I.G Window Shopper SB14269 Only You SB05190 6Ix9ine 2 Chainz Feat Drake Gotti (Clean) ME05164 No Lie (Clean) SB27103 Gummo (Clean) SB32797 2 Play And Thomas Jules And Jucxi D 6Ix9ine Feat. Dj Spinking Careless Whisper ME00102 Tati (Clean) SB33521 21 Savage Feat. Offset, Metro Boomin And A Great Big World Feat. Christina Aguilera Travis Scott Say Something ME03194 Ghostface Killers ME04019 A Little Night Music 2Pac Send In The Clowns ME00572 Changes SB07950 A R Rahman And Pussycat Dolls 2Pac And Dr Dre Jai Ho (You Are My Destiny) ME01867 California Love SB04883 Aaliyah 2Pac And Eric Williams Age Ain't Nothing But A Number SB03566 Do For Love SB07275 Are You That Somebody SB07547 2Pac And Kc And Jo Jo Back And Forth SB03062 How Do U Want It SB05238 I Care 4 You SB11129 3 Of A Kind More Than A Woman SB11128 Baby Cakes ME00044 Rock The Boat SB12016 30 Seconds To Mars Try Again SB09709 Up In The Air ME02907 Abba 3Oh!3 Chiquitita ME00982 Don't Trust Me ME01942 Dancing Queen ME00146 3Oh!3 And Katy Perry Does Your Mother Know ME01124 Starstrukk ME02145 Fernando ME00989 3Oh!3 And Kesha Gimme Gimme Gimme ME00219 My First Kiss ME02263 I Have A Dream ME00288 4 Non Blondes Knowing Me Knowing You ME00372 What's Up SB02550 Mamma Mia ME00425 411 Money Money Money ME00449 Dumb ME00175 S.O.S ME00560 Teardrops ME00651 Super -

The Life & Rhymes of Jay-Z, an Historical Biography

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 Omékongo Dibinga, Doctor of Philosophy, 2015 Dissertation directed by: Dr. Barbara Finkelstein, Professor Emerita, University of Maryland College of Education. Department of Teaching and Learning, Policy and Leadership. The purpose of this dissertation is to explore the life and ideas of Jay-Z. It is an effort to illuminate the ways in which he managed the vicissitudes of life as they were inscribed in the political, economic cultural, social contexts and message systems of the worlds which he inhabited: the social ideas of class struggle, the fact of black youth disempowerment, educational disenfranchisement, entrepreneurial possibility, and the struggle of families to buffer their children from the horrors of life on the streets. Jay-Z was born into a society in flux in 1969. By the time Jay-Z reached his 20s, he saw the art form he came to love at the age of 9—hip hop— become a vehicle for upward mobility and the acquisition of great wealth through the sale of multiplatinum albums, massive record deal signings, and the omnipresence of hip-hop culture on radio and television. In short, Jay-Z lived at a time where, if he could survive his turbulent environment, he could take advantage of new terrains of possibility. This dissertation seeks to shed light on the life and development of Jay-Z during a time of great challenge and change in America and beyond. THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 An historical biography: 1969-2004 by Omékongo Dibinga Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2015 Advisory Committee: Professor Barbara Finkelstein, Chair Professor Steve Klees Professor Robert Croninger Professor Derrick Alridge Professor Hoda Mahmoudi © Copyright by Omékongo Dibinga 2015 Acknowledgments I would first like to thank God for making life possible and bringing me to this point in my life. -

Summer Institute Class of 2019 Individual Pieces Copyright ©2019 by Their Respective Authors

Multitudes edited by Siyanda Mohutsiwa The Summer Institute Class of 2019 Individual pieces copyright ©2019 by their respective authors. All rights reserved. International Writing Program 430 North Clinton Street, Shambaugh House Iowa City, Iowa 52245 United States of America www.iwp.uiowa.edu/programs/summer-institute Contents Foreword vi Peter Gerlach . vi Acknowledgements ix Contributors x 1 Dusk 1 Ghazal . 2 Azhar Wani . 2 Bargain Witchcraft . 3 Tanvi Chowdhary . 3 The Godfather . 14 Cherene Aniyan Puthethu . 14 Fair is Lovely . 18 Suyashi Smridhi . 18 2 Night 22 golden shovel ending in outer space after fleetwood mac .................... 23 Anna Sheppard . 23 What I Look To When Holdin' My Tongue . 24 Darius Christiansen . 24 i Contents Sandalwood . 25 Amna Shoaib . 25 Hermanita de la Mar . 29 KayLee Chie Kuehl . 29 3 Midnight 35 Table Etiquette . 36 Ashley Hajimirsadeghi . 36 Sapphirical Slick . 38 Darius Christiansen . 38 Almost Over . 40 Mahnoor Imran Sayyed . 40 Ward SSK 37: Eric . 50 Medha Faust-Nagar . 50 4 Small Hours 51 Altar . 52 Nyeree Boyadjian . 52 Capital ............................ 53 Nyeree Boyadjian . 53 Taxi . 54 Jishnu Bandyopadhyay . 54 Intruder . 65 Amna Shoaib . 65 The Reflection . 67 Fazila Nawaz . 67 5 Dawn 69 seasonal . 70 Anna Sheppard . 70 Hurricane . 72 Ashley Hajimirsadeghi . 72 Home from The Hospital . 73 Medha Faust-Nagar . 73 ii Contents Passing . 75 Aalia Waqas . 75 The Way Things Are . 76 Anna Magana . 76 House Key . 84 Martina Litty . 84 6 Noon 90 Absence . 91 Hafsa Nouman . 91 Six Months . 94 Payal Nagpal . 94 Yes, You Are . 97 Hafsa Ghani . 97 On Air . 100 Aalia Waqas . 100 The Safe Side . -

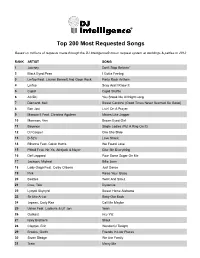

Most Requested Songs of 2012

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence® music request system at weddings & parties in 2012 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 2 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 3 Lmfao Feat. Lauren Bennett And Goon Rock Party Rock Anthem 4 Lmfao Sexy And I Know It 5 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 6 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 7 Diamond, Neil Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 8 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 9 Maroon 5 Feat. Christina Aguilera Moves Like Jagger 10 Morrison, Van Brown Eyed Girl 11 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 12 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 13 B-52's Love Shack 14 Rihanna Feat. Calvin Harris We Found Love 15 Pitbull Feat. Ne-Yo, Afrojack & Nayer Give Me Everything 16 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 17 Jackson, Michael Billie Jean 18 Lady Gaga Feat. Colby O'donis Just Dance 19 Pink Raise Your Glass 20 Beatles Twist And Shout 21 Cruz, Taio Dynamite 22 Lynyrd Skynyrd Sweet Home Alabama 23 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 24 Jepsen, Carly Rae Call Me Maybe 25 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 26 Outkast Hey Ya! 27 Isley Brothers Shout 28 Clapton, Eric Wonderful Tonight 29 Brooks, Garth Friends In Low Places 30 Sister Sledge We Are Family 31 Train Marry Me 32 Kool & The Gang Celebration 33 Sinatra, Frank The Way You Look Tonight 34 Temptations My Girl 35 ABBA Dancing Queen 36 Loggins, Kenny Footloose 37 Flo Rida Good Feeling 38 Perry, Katy Firework 39 Houston, Whitney I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 40 Jackson, Michael Thriller 41 James, Etta At Last 42 Timberlake, Justin Sexyback 43 Lopez, Jennifer Feat. -

Poem - Untitled

Mans: Poem - Untitled Poem - Untitled Jasmine Mans Journal of Hip Hop Studies, Special Issue I Gotta Testify: Kanye West, Hip Hop, and the Church Volume 6, Issue 1, Summer 2019, pp. 99–102 DOI: https://doi.org/10.34718/1v4z-6z60 ____________________________________ Published by VCU Scholars Compass, 2019 1 Journal of Hip Hop Studies, Vol. 6, Iss. 1 [2019], Art. 12 Poem - Untitled Jasmine Mans The audience asks Kanye If he remembers The song about God... To speak about the spirituality of Kanye West, we first have to discuss the spirituality of the Black Man, because that is the identity he holds. It’ll also be valuable to explore, what the Negro spiritual is and the relationship between music that Black slaves used and how we see remnants of those origins in contemporary Hip Hop. Negro people held on to song as a means of communication, education, and religion. Though, I never considered the actual term “Negro Spiritual.” These songs held together the spirit of the Negro. These Negro Spirits outlined literal maps to freedom. The Black song is still very much so rooted in ideas of “freedom” and “God”. The slaves relied on song for the truth. The Negro slaves relied on the metaphor in those songs for strategy. We still see it. Many Black men often see themselves in the symbolism of God. God as a Father, God as a protector, God as someone to be worshipped. Each person learns and participates in spirituality differently; Black Boy be given song Song be sway and hymn Black boy be given song Even before God Black boy be given tick, and bang. -

From Jay-Z to Dead Prez: Examining Representations of Black

JBSXXX10.1177/0021934714528953Journal of Black StudiesBelle 528953research-article2014 Article Journal of Black Studies 2014, Vol. 45(4) 287 –300 From Jay-Z to Dead © The Author(s) 2014 Reprints and permissions: Prez: Examining sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0021934714528953 Representations of jbs.sagepub.com Black Masculinity in Mainstream Versus Underground Hip-Hop Music Crystal Belle1 Abstract The evolution of hip-hop music and culture has impacted the visibility of Black men and the Black male body. As hip-hop continues to become commercially viable, performances of Black masculinities can be easily found on magazine covers, television shows, and popular websites. How do these representations affect the collective consciousness of Black men, while helping to construct a particular brand of masculinity that plays into the White imagination? This theoretical article explores how representations of Black masculinity vary in underground versus mainstream hip-hop, stemming directly from White patriarchal ideals of manhood. Conceptual and theoretical analyses of songs from the likes of Jay-Z and Dead Prez and Imani Perry’s Prophets of the Hood help provide an understanding of the parallels between hip-hop performances/identities and Black masculinities. Keywords Black masculinity, hip-hop, patriarchy, manhood 1Columbia University, New York, NY, USA Corresponding Author: Crystal Belle, PhD Candidate, English Education, Teachers College, Columbia University, 525 West 120th Street, New York, NY 10027, USA. Email: [email protected] Downloaded from jbs.sagepub.com at Mina Rees Library/CUNY Graduate Center on January 7, 2015 288 Journal of Black Studies 45(4) Introduction to and Musings on Black Masculinity in Hip-Hop What began as a lyrical movement in the South Bronx is now an international phenomenon. -

Music Review Kanye West, Jesus Is King US 2019, Def Jam Recordings

Andre L. Price Music Review Kanye West, Jesus Is King US 2019, Def Jam Recordings As any emcee should, Kanye West has developed and matured as a produc- er and lyricist since his 2004 triple-platinum debut project, College Dropout. West’s Gospel project, Jesus Is King, is his ninth studio project and the fol- low-up to his June 2018 release, Ye. After delays, Jesus Is King was released on 25 October 2019. For West, openly talking about Jesus in his music is not new, for he rocked the mainstream hip-hop world in 2004 when he re- leased the single “Jesus Walks”, the final single to be released from College Dropout. Jesus Is King features eleven tracks totaling 27 minutes and 4 seconds, which is short for either a secular or gospel hip-hop project.1 Interestingly, significant changes were made to the track listing order on the album. Kim Kardashian-West announced the tracks and order in August 2019, but the list- ing and order released by Kanye West in October 2019 were markedly differ- ent.2 Such a change could suggest an earlier lack of clarity on what the album was going to be. West did promise that Jesus Is King would be “fully immersed in religion […] with lyrics about God, being saved, and minimal cursing”.3 Jesus Is King employs several aspects of Black Christian worship, from mass choir to melodic organ. West takes the best of the Black gospel tradition, in- fusing it with his own lyrical genius to proclaim what God has done for him, which is best expressed on the track “God Is”, a remake of the classic spiritual. -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with James Poyser

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with James Poyser Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Poyser, James, 1967- Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with James Poyser, Dates: May 6, 2014 Bulk Dates: 2014 Physical 7 uncompressed MOV digital video files (3:06:29). Description: Abstract: Songwriter, producer, and musician James Poyser (1967 - ) was co-founder of the Axis Music Group and founding member of the musical collective Soulquarians. He was a Grammy award- winning songwriter, musician and multi-platinum producer. Poyser was also a regular member of The Roots, and joined them as the houseband for NBC's The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon. Poyser was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on May 6, 2014, in New York, New York. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2014_143 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Songwriter, producer and musician James Jason Poyser was born in Sheffield, England in 1967 to Jamaican parents Reverend Felix and Lilith Poyser. Poyser’s family moved to West Philadelphia, Pennsylvania when he was nine years old and he discovered his musical talents in the church. Poyser attended Philadelphia Public Schools and graduated from Temple University with his B.S. degree in finance. Upon graduation, Poyser apprenticed with the songwriting/producing duo Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff. Poyser then established the Axis Music Group with his partners, Vikter Duplaix and Chauncey Childs. He became a founding member of the musical collective Soulquarians and went on to write and produce songs for various legendary and award-winning artists including Erykah Badu, Mariah Carey, John Legend, Lauryn Hill, Common, Anthony Hamilton, D'Angelo, The Roots, and Keyshia Cole. -

Metric Ambiguity and Flow in Rap Music: a Corpus-Assisted Study of Outkast’S “Mainstream” (1996)

Metric Ambiguity and Flow in Rap Music: A Corpus-Assisted Study of Outkast’s “Mainstream” (1996) MITCHELL OHRINER[1] University of Denver ABSTRACT: Recent years have seen the rise of musical corpus studies, primarily detailing harmonic tendencies of tonal music. This article extends this scholarship by addressing a new genre (rap music) and a new parameter of focus (rhythm). More specifically, I use corpus methods to investigate the relation between metric ambivalence in the instrumental parts of a rap track (i.e., the beat) and an emcee’s rap delivery (i.e., the flow). Unlike virtually every other rap track, the instrumental tracks of Outkast’s “Mainstream” (1996) simultaneously afford hearing both a four-beat and a three-beat metric cycle. Because three-beat durations between rhymes, phrase endings, and reiterated rhythmic patterns are rare in rap music, an abundance of them within a verse of “Mainstream” suggests that an emcee highlights the three-beat cycle, especially if that emcee is not prone to such durations more generally. Through the construction of three corpora, one representative of the genre as a whole, and two that are artist specific, I show how the emcee T-Mo Goodie’s expressive practice highlights the rare three-beat affordances of the track. Submitted 2015 July 15; accepted 2015 December 15. KEYWORDS: corpus studies, rap music, flow, T-Mo Goodie, Outkast THIS article uses methods of corpus studies to address questions of creative practice in rap music, specifically how the material of the rapping voice—what emcees, hip-hop heads, and scholars call “the flow”—relates to the material of the previously recorded instrumental tracks collectively known as the beat. -

***Thesis Manuscript for Pr Uricchio

A Proposal for a Code of Ethics for Collaborative Journalism in the Digital Age: The Open Park Code by Florence H. J. T. Gallez B.A. English and Russian The University of London, 1996 M.S. Journalism Boston University, 1999 Submitted to the Program in Comparative Media Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Comparative Media Studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology June 2012 © 2012 Florence Gallez. All rights reserved The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: __________________________________________________ Program in Comparative Media Studies June 2012 Certified by: ________________________________________________________ David L. Chandler Science Writer MIT News Office Accepted by: ________________________________________________________ William Charles Uricchio Professor of Comparative Media Studies Director, Comparative Media Studies 1 A Proposal for a Code of Ethics for Collaborative Journalism in the Digital Age: The Open Park Code by Florence H. J. T. Gallez Submitted To The Program in Comparative Media Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Comparative Media Studies ABSTRACT As American professional journalism with its established rules and values transitions to the little-regulated, ever-evolving world of digital news, few of its practitioners, contributors